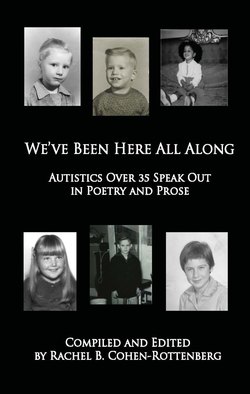

Читать книгу We've Been Here All Along: Autistics Over 35 Speak Out in Poetry and Prose - Rachel Inc. Cohen-Rottenberg - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеRachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg is a wife, mother, writer, and artist who was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome at the age of 50. After receiving her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English from the University of California at Berkeley, she spent many years as a technical writer and homeschooling mother, and now lives a quiet life in rural Vermont.

The Blessings of Being a Tomboy

Tomboy. Remember that word?

These days, it has all but disappeared from the English language. My husband tells me that in the 1980s, people sometimes called his daughter a tomboy because she excelled at athletics. He and his late wife always corrected them with a variation of the following statement: “Our daughter is not a tomboy. She is a strong girl.”

While this nomenclature might have worked for my stepdaughter’s generation, it would not have worked for me. Growing up athletic in the mid-1960s, before Title IX and the women’s movement, I was a tomboy, and I relished the word. Neither just a boy nor just a girl, I could be different. My sense of “otherness” had some kind of name. It was a name that gave me what I needed most: a way into the world of other children.

The road to my becoming a tomboy began when my grandparents went to the 1965 World’s Fair and came home with the most unlikely of gifts: a baseball glove. I was seven years old. When my grandfather took the gift out of the package, my jaw dropped. Why had they brought me a baseball glove? I had never expressed any interest in the game. Were my parents behind it?

As I stood gazing at this odd new possession, my grandfather explained how to use it. He told me to catch the ball in the webbing between the thumb and the forefinger, and to throw the ball with my other hand. Because I was a leftie, he put the glove on my right hand. Then, he lightly tossed me my very first baseball.

I was immediately hooked. If I could have stood out in the backyard tossing the ball back and forth with him forever, I would have done it. As it was, I decided to learn all I could about baseball. I started to follow the Red Sox. I avidly studied the mannerisms of all the players and soon became an accomplished mimic. Determined not to “play like a girl,” I learned how to slide, how to catch, and how to throw. By the time I was eleven, I could throw a fastball, a curveball, a slider, and a forkball.

Of course, officially, I was not a tomboy. Officially, I was still a girl and, therefore, not allowed to play Little League. So my games were all neighborhood pick-up games. Every day, I’d run home from school, change out of my dress, and set out to find a group of kids. One afternoon, as I ran out the back door, I realized that someday I would have to do something other than assemble another ad-hoc team. Someday, in the unseen and distant future, I would be a grownup.

But not now. Not yet. I had a game to play.

When I did think about becoming a grownup, my fantasies centered almost exclusively around baseball. I wasn’t just planning to become the first woman to play for the Red Sox. There was more — much more. I would lead the team to victory in the World Series by pitching a perfect game.

Every night, before I went to sleep, I rehearsed the entire scenario. Dressed like a boy, my long hair hidden under my Red Sox cap, I’d take the mound for Game 7. Inning after inning, no one on the opposing team would hit a ball out of the infield. Nor would I give up a single walk.

As the innings ticked by, the suspense would increase. By the top of the ninth inning, a hush would come over the crowd. When I finally struck out the last batter, I’d take off my cap, throw it into the air, let my hair come down, and show the world that I was really a girl. Pandemonium would ensue. The other players would carry me off the field on their shoulders to the roar of an amazed and grateful public.

My interior life was quite rich.

While things did not turn out quite as I’d planned, baseball gave me many gifts that might otherwise have eluded me.

The sensory experience itself was a joy. I loved the smell of a new leather glove, the sound of the bat meeting the ball, and the feeling of the dirt as I slid into home. When I played baseball, my senses gave me great delight and a sense of accomplishment.

Playing baseball also relieved me of the pressure of socializing with words. Instead of hanging around on the playground conversing, I could run and move and shout. Freed from the onus of having to stand still in a group and search for the social nuances that eluded me, I could be aggressive, loud, and tough. In a baseball game, I was never awkward. I knew just what to say and what to do. When I yelled, “He can’t hit! Strike him out!” no one looked at me strangely. I was part of something.

Of course, my tomboy days did not last as long as I’d hoped. Decades have come and gone since then, and with them, many struggles. Yet when I look back on my girlhood, I can feel the sense of pride, strength, and possibility that were mine when I wore my baseball glove and took to the field.

In those moments, being “other” was not a bad thing. Being “other,” in fact, was wonderful.