Читать книгу Wonderful to Relate - Rachel Koopmans - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Narrating the Saint’s Works: Conversations, Personal Stories, and the Making of Cults

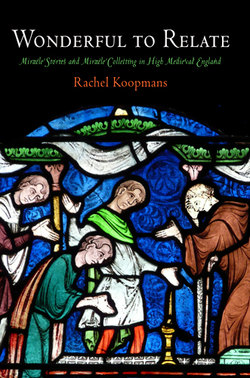

In the early 1170s, a judge in Bedford sentenced Eilward of Westoning to blinding and castration for petty thievery. Eilward, a pauper, was duly blinded—a jailor stabbed his eyes with a knife—and castrated. Some days later, however, after asking Thomas Becket for help, Eilward discovered that he could see again. Benedict of Peterborough, one of the two monks at Canterbury who recorded this story in a miracle collection, describes how people came to see Eilward in Bedford and hear his tale: “Word of this went out among the vicinity, and the new thing attracted no small multitude of people.”1 As Eilward traveled to Canterbury to give thanks at Becket’s tomb, he told his story to crowds along the road, a scene later pictured in an early thirteenth-century glass panel in Canterbury Cathedral (Figure 1). The original inscription to this panel read, “The people stand by as he narrates the mighty works of the saint” (ASTAT NARRANTI POPULUS MAGNALIA SANCTI).2 Eilward’s story caused such a buzz and was picked up and retold so often that it beat him to Canterbury. The Christ Church monks, Benedict comments, had heard about Eilward’s miracle from many others before he arrived.3

While the extent of the oral circulation of Eilward’s story was clearly extraordinary, the references to conversation, speech, and oral storytelling in the written accounts of his miracle are not. Medieval miracle collections are full of such references: as John McNamara has pointed out, the analysis of hagiographic texts often “reveals surprising amounts of information about the tellings of these legends in their own contexts.”4 Simon Yarrow writes of how “miracle collections are packed with people in conversation,” and he does not exaggerate.5 For example, in a collection of the miracles of Modwenna, Geoffrey of Burton describes how Abbot Nigel brought a certain Godric, who had accidentally swallowed a pin-brooch and nearly died as a result, to Queen Matilda, “who loved to hear about the miracles of the saints. He showed the man to her and told the story of what had happened to him, also recounting many other occasions on which the virgin Modwenna had declared through miracles that she was in heaven with the Lord.”6 In his collection of the miracles of Edmund of Bury, Osbert of Clare recounts how a paralyzed man healed by Edmund told his story to Tolinus, the sacrist of Bury, who told Abbot Baldwin, who called all the monks together, along with some lay people, and had the healed man stand in the middle of them and retell his story.7 An anonymous clerk of Beverley, whose collection of the miracles of John of Beverley is particularly rich with oral references, concludes a story about a deaf-mute by describing how “as a schoolboy I saw this elderly man … and I knew him very well … with the younger boys sitting or standing around, he used to tell how the Lord, through St. John, gave hearing and speech to him.”8 This same clerk recounts in another chapter how his parents “asked me if I knew the crippled girl who was accustomed to go begging from door to door. When I replied that I did not know her at all, they were amazed at this when she [and her miracle] were very well known by very many men and women.”9

Figure 1. Eilward of Westoning tells his story. Canterbury Cathedral, Trinity Chapel Ambulatory Window n.III (16). Author’s photograph used with the kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral.

In this chapter and the next, I consider the dimensions and dynamics of what R. W. Southern dubbed the “chattering atmosphere” behind the texts of miracle collections.10 Though questions about orality have engaged scholars of the medieval past for some time, little close attention has thus far been focused on the oral creation and circulation of miracle stories. As Catherine Cubitt has noted, “historians have tended to focus upon questions of orality and literacy in governmental administration and legal dealings, while amongst literary scholars, the most pressing questions have concerned the composition of Old English poetry and the nature of heroic verse.”11 Most studies of oral storytelling in a hagiographic context, including Cubitt’s own, are focused on stories with folkloric motifs: a holy man throwing a key in a river only to recover it later in the stomach of a fish, for instance, or a wolf guarding the decapitated head of a holy king, rather than a story like that of Eilward of Westoning’s healing.12 Brian Patrick McGuire, who has examined the “oral sources” of Caesarius of Heisterbach’s Dialogus Miraculorum, a mammoth early thirteenth-century miracle collection, is one of the few to attempt to say something specific about the speakers behind collections of posthumous miracles. McGuire catalogues the different types of people who told Caesarius miracle stories, finding that he heard stories from Cistercian monks from his own house, Cistercian monks from other houses, abbots, Benedictine monks, laybrothers, secular canons, priests, nuns, and the laity.13 McGuire demonstrates in the course of this study, moreover, that Caesarius derived 95 percent of his stories from oral sources, as opposed to just 5 percent from written sources.14 The two massive Christ Church collections for Thomas Becket, the closest comparative example to the Dialogus among the collections produced in high medieval England, show very similar proportions of oral vs. written sources, about 94 to 6 percent.15 Most shorter collections show no evidence of the use of written sources whatsoever. The stories in the collections of Geoffrey of Burton, Osbert of Clare, and the anonymous clerk at Beverley mentioned above appear to have been derived 100 percent from oral sources.16

It is, of course, impossible to extract the original oral stories from the written collections, but this should not deter us from exploring and taking account of the many references to speech and conversation in the texts. Research concerning “conversational stories” and “conversational analysis” has burgeoned in recent years in sociology, linguistics, and other disciplines in the social sciences and humanities. This work provides a very valuable resource for historians interested in texts like miracle collections, and I draw on it frequently in this chapter and the next.17 In the first part of this chapter, I suggest that the principal oral narrative form behind posthumous miracle collections was what researchers term the “personal story.” This identification is important because it can help us block out basic answers to questions such as how many stories might have been available to collectors, who would have created and told such stories, and how long such stories likely remained in oral circulation. In the second part of the chapter, I take something of a social scientist approach myself, and focus my attention on one particularly illuminating story—the miracle of a knight of Thanet as retold by Osbern of Canterbury in a collection composed in the early 1090s. I use this narrative as a means to draw out the essential dynamics of personal miracle stories and to consider what kinds of things were likely lost in Osbern’s textual rendering of his conversation with the knight. Though most particulars about the oral creation and exchange of the stories preserved in medieval miracle collections are forever beyond our grasp, it is vital to keep in mind the original complexity and emotional force of these stories—otherwise, we can never come to grips with what it meant to be a medieval miracle collector. At the close of the chapter, I argue that these conversational narratives were the lifeblood of cults.

The Volume, Tellers, and Longevity of Personal Miracle Stories

When reflecting on the oral exchange of miracle stories, medievalists tend to think first in terms of “oral tradition,” that is, stories that were passed down and most akin to folktales. These are the kinds of miracle stories that fill saints’ vitae—the story of otters drying a saint’s feet with their fur, for example, or a saint hanging up his cloak on a sunbeam—and one can find examples of them in posthumous miracle collections as well. Collectors describing a history of a long-lasting cult would sometimes draw on legendary stories of vengeance or marvels. For instance, at the close of his life of the murdered Archbishop Ælfheah (d.1012), Osbern of Canterbury describes how a wooden oar, dipped in the dead archbishop’s blood, sprouted and blossomed the next day.18 A similar “flowering staff” motif can be found in other hagiographic texts.19 To take another example, an anonymous early twelfth-century collector of the miracles of Swithun described how an elderly woman was dragged from her bed by a wolf. When she invoked Swithun’s name, she was able to flee and outrun an entire pack of wolves.20 On occasion, one can find such folkloric stories in the collections of miracles of saints recently dead. William of Canterbury tells a story about a pet starling caught in the talons of a hawk in his collection for Thomas Becket. When the starling squawked the name of the martyr, the hawk fell dead and released the starling unharmed.21

The vast majority of stories found in high medieval miracle collections, however, have quite a different ring. William of Canterbury made up his collection almost wholly from stories like that of Eilward of Westoning—stories that living people told about their own experiences. The miracles of the man who swallowed the pin-brooch, the paralyzed man healed by Edmund, the deaf-mute and the crippled girl healed by John of Beverley—these were all stories about the self. The anonymous collector of Swithun’s miracles mainly focused on such stories too. He describes, for instance, how a priest’s servant was extremely ill and in intense pain until he was brought to Swithun’s shrine, where he recovered after thrashing about on the floor and having a terrible nosebleed, and how a deaf boy supported by the monks, so silent that he “possessed the habits and nature of a fish,” recovered his hearing and began to speak.22 In his study of the twelfth-century miracle collection of Our Lady of Rocamadour, Marcus Bull has suggested that “we should treat the majority of miracle stories as the end-product of genuine attempts to formulate explanations of real experiences.”23 Even very brief chapters from the collections, such as the following from Benedict of Peterborough’s collection for Becket, appear to echo a story of personal experience: “In the same abbey another person was extremely swollen up. To say it shortly, after he drank the martyr’s water his stomach returned to its former size.”24 As bare as it is, this account almost certainly originated in someone’s telling of an experience of illness, of drinking, and of recovery of health—a story that likely meant a good deal to the teller.

Paging through miracle collections, one finds stories of personal illness and recovery, peril and rescue, oaths forgotten and remembered, injuries and punishments, and so on and on—there are thousands of such stories in the English miracle collections alone. Researchers in folklore studies and the social sciences term these stories “personal experience narratives,” “conversational narratives,” “memorates,” or, simply, “personal stories.”25 As these researchers have shown, the borders between “memorates” and “fabulates” are porous. A personal experience narrative might evolve into a folktale-like story over time (might something like that have happened with the old woman and the wolf?), while a folktale-like story might inspire new miracle stories of personal experience (the starling story could encourage people in a dangerous situation to invoke Becket).26 Yet most medieval miracle stories can be easily placed within one camp or the other, and it is crucial not to blur the distinctions between the two too much. Folktale-like stories tend to act in certain ways, conforming around certain structures and following certain dynamics of oral production and exchange; personal stories tend to act in quite different ways.

Most medieval miracle collectors were interested in hearing and preserving personal stories. As we read their texts, we need to orient our thinking to the dynamics and characteristics of such narratives. When miracle collectors exclaim at the sheer volume of stories available to them and complain that they can not possibly tell them all, for instance, we should believe them. To take just a few examples of such complaints, at the close of his account of a man recovered from a fever, the anonymous collector of the miracles of the Hand of St. James at Reading writes, “in a similar way and by a similar remedy another knight named Ralph Gilbuin was cured of a similar disease, as also were so many others, both men and women, that I cannot cover them all in this account.”27 A collector of the miracles of St. Bartholomew in London similarly despaired at the prospect of telling all the stories of the “men of the seaports”: “very many of them are wont to visit his holy church every year with lamps and peace offerings of oblations and to tell joyfully of his many miracles worked among them.”28 The anonymous Beverley collector noted, “the passage of time would detain me for a very long time if I wished to write down every single release of prisoners through the merits of St. John.”29

Such statements about the volume of miracle stories are so prevalent, particularly in prologues of miracle collections, that they are usually taken as a rhetorical device and pious propaganda.30 But the oral form at issue here is the personal story, “the most common form of narrative the world over,” in the words of Elinor Ochs and Lisa Capps.31 Charles Keil has commented that “even if we calculate just one personal experience narrative per person, the planet’s proven narrative reserves are staggering, and the folklore empire will never suffer a scarcity of resources.”32 It is quite believable that the collectors at Reading, London, and Beverley heard far too many stories about recoveries from fevers, peril at sea, and released prisoners to try to tell them all. A good comparative example is the experience of a sociologist interested in oral stories told about saints, Candace Slater, who did field research in Brazil and Spain in the 1980s. To keep her projects “manageable,” Slater decided to eliminate all narratives based on personal experience from her source base, despite the fact that these were by far the easiest stories for her to elicit. In defense of this decision, Slater notes that in fifteen years 47,079 accounts of personal miracle stories were reported to those in charge of the canonization procedure of one of her saints.33

Folkloric stories are collective, communal creations. Personal stories are different. Individuals make them about themselves, all the time—it takes no special storytelling skill to make them, nor any special permission or expertise to claim that an experience is the result of divine intervention. Oral stories do not lend themselves to quantification, but there seems little question that there would have been many more personal miracle stories than folkloric miracle stories in circulation at any given time. Some cults would have been bigger than others, of course, but when collectors say in their prologues that there were many stories they were not recounting, most of them were likely telling the plain truth. The fact that compilers of miracle collections so rarely plagiarized from others is particularly suggestive. In her study of dozens of collections from France, Patricia Morison remarks, “of many hundreds of individual miracle-stories there is hardly a single duplication.”34 The same can be said about English miracle collections. Finding material, even for the laziest collectors, never seems to have been a problem.35

We need, then, to think in terms of large quantities. We also need to think of these stories as being exchanged in the same social circles where personal stories usually circulated. That is, every social circle, including the highest. In his study of Caesarius of Heisterbach’s Dialogus Miraculorum, Brian Patrick McGuire writes that the General Chapter of the Cistercian order should be seen as “a great yearly exchange center for stories … it seems to have been a general practice for the assembled abbots to share with each other edifying stories concerning monks in their own houses.”36 A text that provides a particularly interesting glimpse into this high-level circulation is the Dicta Anselmi et Quaedam Miracula, a text written by the Christ Church monk Alexander of Canterbury between about 1109 and 1116.37 In the Dicta section of the text, Alexander recounts some of the formal discourses he heard Anselm give. In the second section, Quaedam Miracula, Alexander retells miracle stories, most of which appear to derive from the time Anselm was exiled from Canterbury. Baldwin, a monk who accompanied Anselm into exile, tells a story about his illness and healing by St. Peter the apostle; Hugh, the abbot of Cluny who hosted Anselm and his exiled companions for a time, tells a story about St. James; Anselm himself tells a miracle story that he had heard as a boy about a judge in Rome; Tytso, a monk in the cell of Blangy in Normandy where Anselm stayed for a time, tells about a child living in the area who was afflicted with a demon; the archbishop of Lyon, another of Anselm’s hosts, tells a story about a clerk in his church named Ademar, and so on.38

As the editors of Alexander’s text point out, “the only connection that most of the thirty-two stories have with Anselm arises from the fact that the author heard them in Anselm’s company.”39 Alexander’s collection paints a picture of archbishops, abbots, and monks gathering together not just to hear Anselm’s formal discourses but also to hear stories from each other’s stock of personal miracles, to exchange news of what the divine had done in that region or in their past experience. The stories Alexander recounts were probably told over a space of some years, but the movement in Alexander’s collection from story to unrelated story and speaker to speaker is probably quite a good portrait of the mishmash of subjects and voices in most conversations about miracles.

Interest in divine activity could and clearly often did form common ground across customary boundaries of social class, age, gender, and religious status, as one sees with the story of Godric, the pin-brooch swallower, standing before Queen Matilda. Catherine Cubitt writes that “oral stories of saintly exploits must have circulated within the intersections between lay and religious, in monastic ambits created not only by pastoral ministry but also by the ties of property ownership and tenurial relations.”40 Innumerable secondhand, many third- or even fourth-hand retellings of personal stories are visible in English miracle collections. Priests retell the stories of their parishioners, abbots of their monks, parents of their children, husbands of their wives, mistresses of their servants, innkeepers of their customers, neighbors of their neighbors, and many other permutations.41 Benedict of Peterborough relates a story about a Becket miracle that he heard from a priest who heard it from a mother who heard it from her children, and also a story he heard from a “truthful man” who heard it from a certain Gilbert who heard it from a blind man.42 One of the longest daisy chains visible in the English collections concerns a woman who worked as the governess of the children of the knight Herbert de Fourches. This woman, whose name is not recorded, had a vision of Æthelthryth in a church in the west country. Prior Osbert of Daventry heard about the vision from the woman’s companions. He retold the story of the vision to Osbert of Clare. Osbert of Clare wrote a letter about the vision and sent it to the monks of Ely. At Ely, the compiler of the Liber Eliensis preserved Osbert’s letter along with many other accounts of Æthelthryth’s miracles: this compiler was at least three stages removed from the woman’s oral description of her vision.43

Some stories were particularly volatile, reaching dozens or even hundreds of listeners besides the collectors. Eilward of Westoning’s miracle is an example of a story that moved very rapidly, like an exploding firework, into many conversational circles. In addition to the crowds of ordinary people who came to hear his story, we know that the burgesses of Bedford, the bishop of Durham, and the monks of Christ Church—and likely many others of their religious status and social rank—came to know the story of this pauper.44 We must envision many more listeners and retellings of stories than are spelled out in the miracle collections, in which stories are usually only moving toward the collectors themselves. If we could map it, the conversational web along which stories about Thomas Becket moved between Bedford and Canterbury, Canterbury and southern England, and England and the wider medieval world on the day Eilward arrived in Canterbury would probably look something similar to the lines of a telephone network. This map would be more bewildering in its complexity the closer we came to the reality of the conversational exchange of miracle stories in this period. Stories about Becket would not be the only ones moving through this network, and all the conversational lines connecting people would be in a constant state of flux.

The stories themselves would also be in a state of flux and constant turnover. In comparison to folkloric miracle stories, the elephants of the oral world—slow-moving, long-lasting, not very numerous—personal miracle stories were more like butterflies. They were everywhere; they fluttered and darted in and out of innumerable conversations; but they were also short-lived. An individual might tell some personal stories again and again throughout his or her life, but most are recounted a few times, or even just once. Some personal stories may be retold after a person’s death, but not as much, and not for long. Once those who knew the creator of the story are dead themselves, the few surviving stories usually die out too. In her study of the stories about Padre Cícero told in Brazil, Candace Slater notes that first person narratives “seldom find their way into a larger communal repertoire.”45

Novelty accounted for a large part of the appeal and rapid dispersal of the personal miracle story. Fresh new stories crowded out the old and then were crowded out in turn. When one looks at which miracle stories from Becket’s early cult were remembered and retold in later generations, one does not find Eilward of Westoning’s story, or any of the other personal stories recounted by the first collectors. They were forgotten. Strikingly, though, there was one story that was remembered: the story of the starling and the hawk. This tale, so different from the others William of Canterbury recorded, is found again in Caesarius’s Dialogus, in Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend, and in other texts.46 It was a durable story—charmingly memorable—in a way that the personal stories were not.

Miracle collectors were well aware that stories had been lost, and that more stories would be lost if they did not write: preservation was, as I will discuss in the chapters below, the chief motivation for high medieval miracle collectors. In the next section, I will take a closer look at one personal story that a miracle collector decided ought to be written down and saved for future generations.

The Knight of Thanet’s Miracle Story

Medieval miracle collectors usually retold personal stories in their collections in an omniscient third person voice, the most compact means of relaying a story. Occasionally, though, a collector tried a different rhetorical tack. One of the more interesting and suggestive of these rhetorical experiments is found in Osbern of Canterbury’s collection of the miracles of Dunstan (written c. 1090).47 Toward the end of this collection, Osbern recounted a story in the form of a conversational dialogue between himself and the man claiming to have experienced a miracle, a knight of Thanet. Perhaps the setting of the conversation stuck in Osbern’s head—the knight and Osbern were walking together on a beach when the knight told him his story. Whatever the reason for the special treatment, Osbern’s account of the knight’s story provides a convenient springboard for a discussion of the complexities of the personal miracle story. Osbern did not have the benefit of the quotation mark (it had not yet been invented), but I will use it here for clarity. The chapter starts in Osbern’s own voice:

When I was on the isle of Thanet, I went walking along the seashore with a knight who had asked me there for his edification. We considered those things that were marvels of God there and drew from them material for good conversation. From there the conversation turned to father Dunstan, as every time I find occasion for speaking about him I always obtain the greatest benefit. Recalling that name, the knight paled, and breathing deeply as if in pain he said, “Oh, how ungrateful I am, I who am forgetful of his great kindnesses.”

“What is it that makes you breathe so heavily?” I said.

“Do you know,” he said, “how much the abbot of St. Augustine’s plagued me while he lived, as he wished to strip my inheritance from me?”

“I know.”

“And do you know that not only was he unable to do anything intemperate, but that it all turned out for my greater glory?”

“Nor is this unknown,” I said, “but I don’t know why you are recounting these things.”

“Know then,” said the knight, “that the night before the day set for the suit between him and me, I recalled how when I was in my house (which is nearby), you frequently used to extol father Dunstan by your accounts. Now, I said to myself, I have the chance to know by experience what I have heard, such that he might be praised. Kneeling in prayer, I said, ‘God of father Dunstan, favor my part today.’ Then giving my body to rest, I saw in my dreams the city of Canterbury, the basilica of the Savior, and the memorial of the father, as if I were resting upon it. I saw a man standing next to it, of decorous form and beautiful garments, holding a lamp of light in his hand. Terrified by his image, I said ‘Who are you, most glorious man?’ He said, “I am the one to whom you prayed for help a short time ago.’ ‘Incredible!’ I said, ‘how quick you are to comfort the suffering! Do you know what the lord threatens?’ He said, ‘Do not fear any of his threats, or weigh them as of any consequence.’”

So the knight spoke. Afterward he turned to me again and said, “you already know the rest, how you and I consulted together, fought, and triumphed.”

“On that day,” I said, “the saint gave a grand sign: while there were many there with polished wit, they left conquered by those few with less polish.” Then, seeing those who were present, I presented to them in words what I now produce in letters.48

The ubiquity and familiarity of personal stories can make them seem rather simple. The recitation of Beowulf by bards, the singing of ballads in the streets of medieval Paris, the fama or oral reputation that mattered so much in medieval law courts, the stories of sprouting oars and flowering staffs—this all feels exotic and complex, and has received substantial study from scholars.49 In contrast, personal stories can seem so straightforward, so reflective of experience itself, that it can appear there is nothing that particularly needs analysis. Scholars have usually assumed that the oral stories miracle collectors heard reflected reality quite closely, and that what needs attention is how collectors would have twisted and shaped these accounts to their own ends. But researchers in the social sciences have found that personal narratives are quite complex constructions—that they are more difficult to analyze, in many respects, than folktales.50 These researchers particularly stress the danger of failing to distinguish between a person’s lived experience and an oral story of that experience. Rom Harré comments, for instance, that “the telling of tales is more readily researchable than the living of lives.”51

Three contexts are essential for decoding the meaning of a personal story: the creator’s own personality and sense of himself or herself; the circumstances in which the story is articulated—place, audience, timing, and so on; and the oral and physical dimensions of the story’s telling.52 This is the kind of data we gauge automatically, often unthinkingly, when we hear and evaluate personal stories from people we know well. But without it, personal stories become extremely hard to dissect, harder, in fact, than stories—like that of the blossoming oar—with less personal content.53 Even with the richness of Osbern’s retelling of the knight of Thanet’s story, it is difficult to probe far into its meaning. We might be able to find out more about the abbot of St. Augustine’s, or inheritance law, or the number of knights on the isle of Thanet, or the position of Dunstan’s tomb in the cathedral, but this information is peripheral to the meaning of the knight’s story. The essential problem with analyzing a narrative like the knight of Thanet’s story at this distance is that we know so little about him. Osbern must have had a sense of what the knight’s inheritance entailed. How much did he need it? Did he have any previous dealings, good or bad, with the abbot of St. Augustine’s? Were other members of the family disputing the inheritance? A personal story is best grasped by someone who has known the teller for years, someone who can place a personal story in the context of others. Did the knight normally tell stories about his anxieties or his dreams? Had he told a story about a miracle before, or was this his first one? In the knight’s personal history, would this story rank its own chapter, or just a footnote? What did the knight’s wife, if he had one, think about all this?

One could multiply these questions, and ask them about any of the personal stories preserved in miracle collections. To catch the full resonance of the knight’s story, we would need to know more than this, however—we would also need to know more about the knight’s relationship with Osbern. The knight and Osbern appear to have been alone as the knight told his story. The two were well acquainted with each other. Not only had they had conversations before this particular walk on the beach, but Osbern had been personally involved in the knight’s lawsuit with the abbot of St. Augustine’s. It also appears that Osbern took the lead in this friendship. He came to talk with the knight at his special request and looks to have been directing the conversation where he wanted it to go. These kinds of things make an enormous difference in how a personal story is told, how it is received, and the meaning it conveys. So much eludes us, though. Did Osbern go to Thanet solely to meet with the knight, or did he have other business there? How did these two come to know each other? Who was the older? Trading personal stories is one of the chief ways people forge bonds with each other: as Sandra Dolby Stahl has commented, “the exchange of personal narratives [is] an emotionally satisfying experience for both the teller and audience…. This intimacy is more marked in the exchange of personal narratives than in other kinds of storytelling.”54 By telling Osbern his story, the knight exposed his anxieties, his dreams, his interpretations, and ultimately himself. Did the friendship between Osbern and the knight change after this story was told?

The specifics of how this all played out are beyond our reach. The complexities of oral performance present yet more difficulties. Personal stories are constructed through the voice, facial expressions, and body language of the teller as much as in the sense of the words. This is the case with the oral delivery of any kind of story, of course, but the stakes are heightened considerably with the personal narrative, stories of the self told by the self. Osbern gives us a few clues, writing that the knight “paled” and “breathed heavily” at the beginning of his story. But did the knight remain pale, or did he perk up? Did he speed up in certain places, slow down in others, speak more loudly, more softly? Did he pause, backtrack, misspeak? Personal stories root themselves in the self in ways even the teller might not grasp. We effortlessly absorb and process these nonverbal cues when we listen and see other people telling their stories, cues that may well contradict the meaning of the words being spoken. Though it is almost all gone now for the stories in miracle collections, we must try to imagine those flesh and blood speakers, to think of the expressions shifting across faces, eyes making contact or looking to the side, shrugging shoulders, sighs, gestures, hesitations—and how all of this invigorated and shaped the meaning of personal stories as they were being told.

To gain a full picture of the telling of these stories, we also have to account for the reaction of listeners. The relationship between teller and audience in the telling of a personal story is a particularly active one. An encouraging question, a comment, a grimace, or a glance away—all these can invigorate, redirect, or halt the telling of a personal story. Personal stories exist in the moment, rarely if ever told the same way twice. Tellers adjust them, sometimes radically, depending on who is listening and how they respond. Osbern gives us a taste of the kind of conversational give and take that most personal stories involve, but again there is so much that we don’t know. Was Osbern rapt during the whole of the knight’s story? How might the knight of Thanet have told his story later or to another companion? Since the meaning of personal stories is so deeply embedded in personalities, relationships, and oral performance, even the most carefully composed texts will fail to convey their complexity.55 Osbern’s textual rendering inevitably deadens and radically simplifies the knight’s story. Still, the power of the personal story is such that even in this severely muted form the reader can feel its pull. Reading this story invites a sense of intimacy with the knight beyond what one would feel, for instance, from reading a charter issued by him.

It also invites a sense of intimacy with the saint at the center of the story. A triumph over an enemy is a common narrative trajectory for a personal story. What makes the knight’s victory in his lawsuit a miracle story is the credit he gives to Dunstan for his success. The knight could have claimed that it was Osbern’s help, or his own skill or luck, that achieved that result. Instead, he links his prayer, his dream, and his success together: Dunstan won the case for him. Dunstan, though dead, becomes the actor at the center of the story, as real a persona as the knight himself. Today, miracles tend to be envisioned in theoretical and nonfigurative terms: a miracle is a breaking of the laws of nature. Most stories in miracle collections have a much more particularized flavor. Dunstan was here. Dunstan helped me. That’s why I won my lawsuit, why I felt better after being sick, why my daughter was saved after falling into the river. Saints might not always be seen or sensed, but they live out posthumous lives in which they continue to care about the people on earth. Rather than reading the knight’s story expecting a lawbreaking event, we should instead read it as a narrative, a story created by the knight to describe how his life and the posthumous life of Dunstan became intertwined.56 It remains very much a personal story. In fact, if anything it is a double personal story, about the knight’s and Dunstan’s personal histories. The knight’s story tells about them both; it packs a double punch. We can term the result a personal miracle story.57

Personal stories define and empower a teller’s sense of identity; personal miracle stories do so as well, indeed even more so. At first, this may seem counterintuitive: the knight certainly now cannot claim the glory of triumphing over the abbot of St. Augustine’s. But this story claims something even better: Dunstan acted for me. This saint, living in heaven, was willing to help me, to enter into my concerns, to respond to my prayer with amazing speed and efficacy. Miracle collectors used exceptionally emotive and powerful language to describe their subject matter. Strikes of lightning were a favorite analogy: saints were said to “flash,” “gleam,” or “shine out” in miracles after their death.58 Somewhat similar effects are evident in modern personal stories recounting the visit of a celebrity—the touch of Princess Diana or an encounter with Michael Jackson. The famed presence enlarges rather than diminishes the creator of the story in the striking blend of abject self-importance that such stories convey.

We cannot know now, of course, what the knight’s story about Dunstan’s aid might have done for his self-image, or how many more times he told it or to whom. There was a reason besides his own self-image that the knight might well have decided to tell his story more than once. He pales and groans at the beginning with good reason. Dunstan would act, but he was not going to speak for himself. In this way, he was like any dead friend. If the knight did not tell the story, Dunstan’s actions would not be known by others. The knight has to tell the story for the silent Dunstan as much as for himself. Osbern had probably heard stories, perhaps many stories, of the knight’s personal experience before this walk on the beach. Listening to this particular story, Osbern gets a double benefit: he finds out not just about the knight’s recent actions, but about Dunstan’s too. Osbern knew the stories from Dunstan’s lifetime long ago better than most. What the knight’s story offered was a sense of Dunstan’s current life, a glimpse of what Dunstan was doing and how he was acting in Osbern’s own present. Precious, thrilling, joyous information, that, even if it was not always easy to interpret. Did Dunstan’s speed in answering the knight’s prayer have something to do with the way the knight worded his request? Did Dunstan’s physical appearance in the dream—a handsome man holding a lamp—have deeper significance? Did Dunstan hold a grudge against the abbot of St. Augustine’s?

Such uncertainties, typical of personal miracle stories, did not usually blunt listeners’ desire for these stories. Unlike the well-worn miracles of a saint’s life, these personal miracles were fresh and new, and their exchange offered an even greater emotional zing than did most personal stories. Knowing more about Dunstan, Osbern can feel more personally attached to him. In the discussion of a mutually beloved divine self, the knight and Osbern can delight in each other’s company even more. Not only that, but the knight’s story suggested possibilities in case Osbern were ever in need of divine aid himself. Personal miracle stories were full of clues for how to get a saint on one’s side. Indeed, a miracle story like the knight’s, though less sensational than a story of sunbeams acting as clotheslines or oars sprouting and flowering, had much more immediate relevance to those listeners hoping for divine help with their own personal problems.

Osbern found the knight’s story so stirring that he immediately retold it himself to new listeners, “those who were present.” Personal stories tend to be retold only among people who have an interest in the creator. Outside of the creator’s familiar circle, interest in his or her stories usually drops dramatically. The difference with the personal miracle story is that there is a second, much wider circle in which the story can circulate: all those who desire news of the saint. Such mobility exacted a cost. When Osbern retold the knight’s story, it lived in Osbern’s face and gestures, in Osbern’s breath and voice. Osbern chose when and where and to whom and at what length he wanted to tell the story. He decided how to introduce and conclude the story, how to mediate every aspect of it. The question is not whether the outlines of the knight’s original story were blurred and deformed, but to what degree. The further a story traveled, the more these effects were compounded. Moreover, if “those present” on the beach did not know the knight, much of the resonance of the story would be lost. The personal miracle story would have been most potent and affecting when told by its creator to close friends, people who could fully appreciate both the personal and the divine ramifications of the story.

The personal miracle story, then, was generally more intense, more desirable, more mobile, and more long-lived than the ordinary personal story, but in its essential characteristics it remained a personal story. Though these stories interested people outside of personal circles and could travel through multiple tellers, they originated in stories people told about themselves. When reading miracle collections, we must keep those individuals before us. They were all as real as the knight of Thanet, and their stories all had a multiplicity of personal resonances and meanings that we will never recover.

Conversations and the Making of Cults

Medieval cults tend to be thought of in terms of their visible manifestations and remains: the relics, the churches, the rituals, the tombs, the pilgrims’ badges, the stained glass, and the texts, the texts most especially.59 Since texts tell us so much about the cults and largely define our own thinking about them, it is easy to slip into thinking that they define cults themselves. But what actually makes a medieval cult? What was its animating essence? In the high medieval period, we should not look to texts in languages most could not read in a scattering of handwritten manuscripts most did not own. We should not even look to liturgies, pilgrimages, or rituals, as these could be carried out when the saints themselves seemed dead and inactive. I believe that what most defined cult, what made people, literate and illiterate alike, think of a cult as living and active, were personal stories of a saint’s intervention. These stories were the warm, pulsing evidence that a saint lived now, acted now, and was worthy of past and future veneration. The creation and circulation of these stories required no money, no pen or parchment, no building, not even the presence of a physical relic, but simply a person seeing a saint’s actions in his or her own life and telling other people about it.

Cult is the knight of Thanet, Osbern, and “those present” talking on a beach about Dunstan’s recent actions. Cult is Eilward of Westoning telling his story about Becket’s healing powers to the crowds in Bedford and along the road to Canterbury. Cult is not, at least not so essentially, Osbern or Benedict writing accounts of these stories later in their cloister. What happened on the beach, what happened along that road, and what happened in far more conversations than these collectors could hear or hope to recount, were the important things. Compared to the tangible texts, these innumerable lost conversations can seem wispy, even untrustworthy, something we might term mere “rumor.” But we should not be blinded to what the oral creation and circulation of personal miracle stories possessed: the easy, all but effortless ability to spread word, to leapfrog social barriers, to create a sense of warm camaraderie, and to energize the veneration of saints. When he created his story about Dunstan, the knight joined or strengthened his association with the larger group of people who saw Dunstan as a saint. Osbern, listening, added another story to his personal store and refreshed his own sense of belonging. Retelling the knight’s story to “those present,” Osbern may have created a sense of cultic association or interest in a group of people who had never heard of Dunstan before. Scholars have argued for the important role of the miracle as a social bond in the medieval period, but it was actually the telling of stories, and not miracles per se, that acted as the bonding device.60 People felt part of the familiar circle of a saint in the way one feels part of anyone’s familiar circle, by sharing, knowing, and especially creating stories about them. Becket became England’s most famous saint through the exchange of stories: these conversations were the generators of cultic communities, groups of people feeling a strong attachment to a saint and believing in his or her power in the world.

Julia Smith has written that “oral traditions of posthumous miracles were more important than written accounts in sustaining a cult.”61 I would go further and say that written accounts were in fact not needed at all. Cults did not need texts or their writers to form, to function, or to be terrifyingly strong. Moreover, a miracle collection, no matter how long or carefully wrought, was itself no guarantee that a cult would grow or continue. Medieval miracle collections need to be viewed as secondary manifestations of the animating discourse: they fed off the oral world far more than they ever added to it.

The medieval cult of saints is often presented as being generated, led, and controlled by the religious aristocrats of the society. Bishops and abbots are envisioned as making cults at tombs for their own self-promotion and interest, with pilgrims responding to the call, experiencing miracles, and depositing their coins.62 But while the religious elite could tell miracle stories and hope to create their own stories of divine intervention—as Osbern did—their exalted status availed them little in the midst of the ever-shifting body of voices and stories that made up a living cult. Working in an age before print and significant levels of literacy, much less television or other powerful communicative tools, the religious elite had extremely limited means of directing the spread of these stories or how they were told. Nor could they generate cults at will. Miracle collections often represent attempts to radically simplify the discourse, to make it sound as though a “we,” the religious, have a “them,” ordinary people, in harness, but while miracle collectors found these sorts of representations satisfying we must not mistake them for the whole reality. The powers inherent in moving miracle stories, some of the most forceful narratives people make, were multidimensional and directional. Moreover, much as we might envision medieval people making up miracles for themselves out of the contingency of their experience, those experiences were still as unpredictable as ours, with no way for them to presage what the divine would or would not do, no matter what they hoped or desired.

Before turning in earnest to the collectors who decided to take some of these oral stories and turn them into texts, in the next chapter I will examine another fundamental feature of this oral world: the ways in which personal miracle stories could be and often were patterned after each other. It would seem that the presence and knowledge of other people’s stories would have little effect on anyone’s own creation. Certainly, all these oral creations were unique: the knight of Thanet’s story, as we have seen, was very much his own. Nevertheless, the production of personal miracle stories was not completely free-form. Those other stories mattered. The flow of conversation had direction, moving in certain channels and not others, constraining individual voices even as it was made up and directed by them.