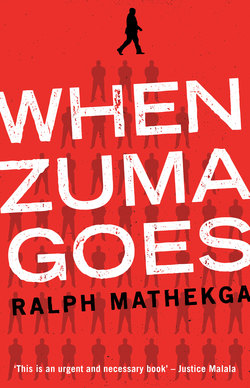

Читать книгу When Zuma Goes - Ralph Mathekga - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE

ОглавлениеThe rise of the ‘man of the people’

The ascension of Jacob Zuma to the presidency of the African National Congress (ANC) is a phenomenon that continues to be seen as an exception to the rule. The explanations for Zuma’s triumph against the odds verge on the miraculous. Just how those odds were stacked against him makes for an interesting story. And in the nation’s collective psyche, Zuma stands as a lone hero who triumphed against a legion of enemies. I was not entirely surprised by Jacob Zuma’s ascension, however; the soil was fertile for the appearance of such a leader. More than that, I believe that if Jacob Zuma did not exist, the populists would have invented him.

The key to how Zuma made it to the ANC presidency, and then became president of the country, lies in understanding the legacy of former president Thabo Mbeki, and in the ongoing evolution of the ANC as a political party. If we look closely at Mbeki’s administration style, particularly the way in which the state started to relate to citizens and political parties, it becomes clear that a gap was created between the party and the institutions of government. And this gap conveniently accommodated the emerging Jacob Zuma cult. Zuma was packaged as an alternative to Mbeki; however, a closer look suggests that Jacob Zuma actually represents a particular way in which citizens are trying to relate to the people in power. And it is the antithesis of Thabo Mbeki’s approach to modernising the state and his relations with citizens. The idea of Zuma as an alternative was created in an attempt to normalise the frosty relationship between citizens and the formal institutions of government.

In 2006, during the personal legal woes that confronted Jacob Zuma after he was fired as deputy president of the country,1 I presented a paper at the third biennial conference of the South African Political Studies Association, held at the University of the Western Cape (UWC). The paper was titled ‘The ANC Leadership Crisis and the Age of Populism in Post-apartheid South Africa’. At the time, Zuma’s problems with the ANC appeared to be a straightforward case of an individual member of the party who had made a mistake by associating with an unsavoury character, namely, Schabir Shaik. Mbeki dealt with the problem by removing Zuma from government. That proved to be the beginning and not the end of the problem.

Zuma was facing corruption charges, which were subsequently followed by rape charges.2 Many South Africans believed this was the end of Zuma’s political career. But Zuma’s personal troubles distracted everyone’s attention from the political circumstances that reigned within the ANC and the country at that time. My argument was that the ANC was shifting towards a populist direction, and the country – at that time – was willing to embrace such a shift. This was, in my view, a moment when the party was searching for a political figurehead with whom people could identify, someone who represented a leadership style different from that of the autocratic Thabo Mbeki. This populist wave was not triggered or created by Jacob Zuma, but he would ride the wave to secure the presidency of the ANC and that of the country, and would later abandon the populist ticket once he became president, surrounding himself with a few trusted friends.

At the time, I argued that recent developments in the South African political landscape had raised questions about the political leadership emerging in the country – and only just a little over a decade after apartheid had ended. Since it came to power in 1994, the ruling ANC had largely defined the leadership fabric in the country, with its political project grounded on a moral appeal derived from the party’s role as a leader of both the liberation movement and the process of transformation. Recent events in South Africa, though, had left the ruling party on the defensive, and the ANC found it necessary to explain itself in terms of the leadership that it stood for. The need for introspection on the part of the ANC seems to have emerged after the dismissal of Jacob Zuma as deputy president in June 2005, due to his alleged involvement in corruption. Zuma was able to mobilise popular support among different ANC structures and within the trade unions, where the populist agenda was increasingly seen as an alternative to Mbeki’s style of leadership.

That was how I understood the political environment in which Jacob Zuma emerged, and how that environment rejected Thabo Mbeki. For me, it has never been about two individuals, but rather about how society and institutions shape their fate. Of course, their responses to circumstances would shape the particular way that Mbeki would exit and Zuma would enter South Africa’s political leadership. But personally, the two men had nothing to do with the main point, which was that it was becoming necessary for one form of leadership to take over from the other. At the time this explanation made sense to me. Eventually the same fate that troubled Mbeki would also trouble Zuma. The main difference between the two leaders in how they dealt with challenges within the party and society is that the one was able to learn from the mistakes of the other: Zuma had the privilege of learning from Mbeki’s mistakes. This explains why Zuma would hold on to power despite the numerous major problems he would encounter. Mbeki, on the other hand, had to write the script from scratch, and he got it wrong.

The framing of the conflict between Zuma and Mbeki is better understood in terms of both leadership style and expectations from the broader society and the party. When his supporters put Zuma forward as an alternative to Mbeki, the case was made that Zuma had a more open and consultative leadership approach.3 This comparison is rather inadequate, because, by that time, Zuma had not occupied any position where his leadership style might have revealed itself. In fact, his leadership style could only be traced back to his role within the exiled ANC during the liberation struggle as the head of counter-intelligence and various secret operations.4 Prior to his 1999 appointment as deputy president of the country, he served as Member of the Executive Council (MEC) for Economic Affairs in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. A minor provincial appointment such as this does not license one to show the sort of leadership that would warrant comparison with a sitting president.

In addition, the position of deputy president is effectively a ceremonial one, unless the individual in that position is so driven that he or she attempts to make something out of it. The deputy’s actual responsibilities largely involve presiding over the reburial of struggle heroes’ remains, attending the funerals of dignitaries and possibly also convening not-so-interesting inter-ministerial committees, which usually fall apart after a few meetings. It is difficult, if not impossible, to recognise a leadership style from someone in this position, which made it convenient to compare Zuma’s virtually non-existent leadership style with Mbeki’s tight grip on power.

By then Mbeki’s leadership style had become apparent over the years, largely in the way he arranged state institutions. In 2000, in a play on Brian Pottinger’s book about PW Botha, The Imperial Presidency, political scientist Sean Jacobs5 was the first to describe Mbeki’s leadership style6 as an ‘imperial presidency’. Mbeki has subsequently written a series of letters attempting to dismiss the idea that he was obsessed with power. At least the former president is aware of the perception that he was aloof.

The idea that Mbeki’s administration was an ‘imperial presidency’ was derived from the way he organised the state bureaucracy. This, in turn, influenced how his political party (the ANC) and ordinary citizens would relate to the state. Assertions were made that Mbeki was a centrist, and that he preferred to concentrate power in a few government institutions that he could personally control. I bought into this idea at first. However, as I began to think it through back in 2006, it became clear that before Mbeki took over as president, following the collapse of the apartheid regime, South Africa had no coherent state bureaucracy. Under apartheid, South Africa had a highly centralised state system aimed at ensuring stability in the country, while pushing against any attempts to delegitimise the regime. The organisation of society centred on the use of the security apparatus, and government did not see itself as obligated to account to citizens. That configuration did not allow for the creation of the type of bureaucracy based on democratic principles, including the separation of powers between the executive, the judiciary and the legislature. Mbeki’s attempt to build a modern bureaucracy was the first concerted effort after apartheid.

President Nelson Mandela had attempted to lay the foundations for a state bureaucracy. But it was Mbeki who consolidated the bureaucracy and gave it a recognisable shape. His approach was not perfect, but it laid a solid basis for what we have today. Before I explain how Mbeki did that, it is important to stress the main point of this analysis: the manner in which Mbeki organised the state bureaucracy produced a situation where his own party grew more and more discontented. They felt restricted in their relations with the state, and this attitude gave rise to the idea that Mbeki was ‘aloof’ and not in touch with the people. This image was grafted onto his personality and his leadership style, and then compared with that of a man who had not yet really developed a leadership style – Jacob Zuma.

Zuma would ultimately encounter problems in crafting his own leadership style because it had already been imagined and assigned to him – as the opposite of Mbeki’s leadership approach. But Mbeki’s own tendency to be overzealous got the better of him when he dreamed of a third term as president of the ANC.7 That mistake cemented the legend of his aloofness and gave it a life of its own. No matter how many letters he would write to explain himself, they only drove home the idea that he was aloof.8

And concerns were emerging in the ANC that Mbeki was going his own way, without sufficient approval from Luthuli House, the party’s headquarters in Johannesburg. At the time, it could be said that most ANC members and South African voters did not yet fathom the idea that a political party and the state are two different things. The party chooses ministers and officials to serve in government, and this may give the impression that the party is the state.

This problem often rears its head in Africa, where political parties in power operate under the illusion that they are the state, and thus the owners of state resources. A good example is Kenya under the leadership of Daniel arap Moi, who became president in 1978. It was only when Moi’s party, the Kenya African National Union (Kanu), lost power in 2002 that the country realised it had been using government offices and resources to carry out party activities. This makes a strong case for the complete separation of government from the ruling party. But any African leader who tries to draw a line between the state and a political party will have to confront a political culture that seems to be well entrenched – and sees no need for such separation. I suppose one of the problems Mbeki encountered was that of separating the party from the state, which led to his falling-out with the party, and eventually to his removal from office before the end of his presidential term.

The distinction between a ruling party and the state is a key principle when it comes to understanding the politics of a post-liberation country such as South Africa. The state is like a plane full of passengers (the nation), who appoint an aircrew and cabin attendants (the ruling party) to fly them wherever they want to go. The crew do not own the aircraft; the passengers employ them. If the flights are smooth, their contracts might be renewed; too many bumpy landings and they’ll be voted out – unless the crew hijacks the plane, of course, which provides a Zimbabwean flavour!

Thabo Mbeki angered many provincial ANC bigwigs when he decided to appoint the premiers of provinces directly, without following the party line of deployment.9 According to party tradition, the ANC provincial chair is naturally in line to become provincial premier. The argument for this approach would be that, as the president of the country and the head of the executive branch of government, the president has the right to select whoever within the party he or she thinks would best implement the government’s mandate. One of the administrative privileges of being the boss should be the ability to select your team, outside party constraints. It is only where the ruling party is not in charge, such as in the Western Cape province, that the president forfeits the chance to appoint a premier.

Thabo Mbeki was criticised for what I believe was an attempt to modernise the post-apartheid bureaucracy. In his own party there were discontented mumbles aplenty, including the accusation that Mbeki focused too much on international affairs and the so-called African agenda. It was said that he was not distributing the resources of the state in accordance with how the party preferred. In cruder terms, some critics said Mbeki was not pushing the ‘party mandate’, as he was obsessed with a Eurocentric version of how the state ought to be. It was whispered that Mbeki’s demeanour was that of a snobbish English gentleman, who dealt with his comrades in an ‘un-ANC’ manner. So Mbeki’s bureaucratic reorganisation of the state was simply branded as coming from his personal obsession with power. This, in my view, is not entirely correct. Even under Jacob Zuma, there has been further consolidation of bureaucracy, and Zuma has not been accused of doing this to increase his power base. This is because Zuma was not suspected of being capable of harbouring sentiments to create and hold on to a power base. The perception that Zuma was a ‘man of the people’ also implied he was not the type of politician who is really interested in power politics. Zuma’s experience in government, however, dispels the naive belief that he is only interested in singing and dancing. Like any politician, he indeed has an interest in latching on to and consolidating political power. What is even more notable about Zuma is that he is willing to trade political power for material benefits, as evidenced by the material enrichment of his children and family during his presidency.

Mbeki, on the other hand, steadfastly built the capacity of the state. In order to implement the complex macroeconomic policy that South Africa adopted after the collapse of apartheid, the state needed to be capable and the bureaucracy needed to be in place. This was achieved under Mbeki, notably in the strength of the National Treasury under Finance minister Trevor Manuel. While the National Treasury’s role, responsibilities and areas of function are well provided for in the Constitution, Mbeki protected its financial management system against populist demands for relaxed fiscal targets.10 Mbeki also protected the South African Reserve Bank’s monetary policy, particularly the inflation targeting practice that has come under severe attack by the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) and some within the ANC.

The protection of such institutions from populist and party onslaught represents further consolidation of bureaucracy in South Africa. But the ANC had yet to learn the lesson that you cannot just spend money as you wish. The idea had not sunk in that you cannot run a deficit to fund policies that you think are important. Fiscal discipline, proper fiscal management and the idea of ‘fiscal reality’ are usually seen as convenient ways of blocking the implementation of progressive policies in newly liberated countries. The absence of these traits in a system usually indicates a poor level of bureaucratic development.

The operation of the Reserve Bank under its governor, Tito Mboweni, also showed further consolidation of state bureaucracy. The idea of inflation targeting, which necessarily requires the constant monitoring of the currency and subsequent protection of its value, came under attack as part of the anti-Mbeki crusade. Critics said that reining in inflation clashed with the nation’s need for rapid industrial development. Cosatu has always maintained that inflation targeting keeps the value of the rand too high, and that the cost of production in local industries is therefore unsustainable. For Cosatu, economic policy – understood in terms of the need to accelerate expenditure and create jobs – should not be constrained. Together with the South African Communist Party (SACP), Cosatu argued that monetary policy should be subjected to the demands for rapid economic growth. In crude terms, Cosatu wants to spend at all costs, in the belief that growth will regulate inflation naturally, not deliberately, as the Reserve Bank has been doing. The attack against this approach intensified under Mbeki, causing headaches for Mboweni.11

Mboweni fended off calls to do away with inflation targeting up until his departure from the Reserve Bank in 2009. His ability to repel such calls was based on Mbeki’s belief in the central bank as part of his bureaucracy, and his devotion to the idea of an independent central bank that would not be easily swayed by the political mood of the day. Mboweni’s retirement as the head of the Reserve Bank was interpreted as the end of the inflation targeting policy. In a deeper sense, Mboweni’s retirement presented an opportunity to tinker with the bureaucracy that had kept South Africa on a recovering fiscal path, with a stable currency and a relatively low debt-to-GDP ratio. This bureaucracy also ensured a low deficit, despite rising government spending on social security grants.

I am in no way of the opinion that Thabo Mbeki was a perfect leader. There are numerous areas where he could have and should have done better. Among the black spots on his presidency was his approach to HIV/Aids. There are some in South Africa who have called for him to be hauled before the International Criminal Court at The Hague to be tried for crimes against humanity because of his stance on HIV/Aids. While this would be an extreme measure, Mbeki certainly undermined the fight against HIV/Aids. Further, the manner in which Mbeki handled calls for an arms deal inquiry before he left office in September 2008 also showed concern with saving the name of the party instead of allowing the pursuit of justice. Mbeki relinquished power while maintaining steadfastly that there was no need for a broader inquiry on the arms deal. He maintained that those who had evidence of wrongdoing relating to the arms deal should present it to the law enforcement authorities.12 Mbeki not only failed to initiate a full-scale investigation into the arms deal, he also frustrated any meaningful inquiry. Jacob Zuma ultimately instituted the Seriti Commission to re-examine the arms deal. Zuma’s commission arrived at the same results as Mbeki, that there was nothing untoward about the controversial deal, despite the conviction of former ANC chief whip Tony Yengeni for impropriety relating to the deal.13 Perhaps the only belief that Mbeki and Zuma share is the conviction that there was no corruption relating to the arms deal.

All of these failings, and others, do not detract from the fact that Mbeki did a sterling job in consolidating state bureaucracy, a bureaucracy that is the envy of many countries on the continent and elsewhere. But with this process came unintended consequences, which created fertile ground for Jacob Zuma to emerge as an alternative to Mbeki. The latter’s attempt to clinch a third term as the president of the party made Zuma even more attractive as a leader.

On a more complex level, it is difficult to build a modern bureaucracy in a situation where the majority of the people are still desperately poor. If attempts are made to build a modern Western-style state bureaucracy amid gross inequality and disturbing poverty levels,14 that bureaucracy will be seen as attempting to shield the state from the influence of the voters, particularly the economically destitute voters who need direct contact with the state as a distributor of opportunities and resources. It has been argued convincingly that poor countries will most likely not be able to sustain democracy.15 This is because of the burden of poverty and inequality on democracy. In a country where the majority of citizens are poor, they would demand rapid response from democratic institutions. This also means that they would find government bureaucracy to be inaccessible; hence they will be more willing to turn away from democracy.

This impasse, which commonly affects newer democracies, often results in difficulties where the founding political party has to transform itself from dispensing the rhetoric of serving the people and bringing government to the people to being a modern party functioning within the limits of a full-fledged bureaucracy. By its nature, bureaucracy requires delegation, and essentially lacks the direct point of contact that newly liberated citizens often yearn for. Bureaucracy and the politics of representation will always be alienating for citizens such as South Africans, the majority of whom have been distant from government except when it policed their affairs under apartheid.

As a founding party of South Africa’s democratic dispensation, the ANC has confronted this challenge in an interesting way. The party naturally became alienated from the general populace, as it presided over a bureaucratic and institutional framework requiring that those in government were not in direct contact with voters. This has resulted in the ANC finding it difficult to manage its own transition from being a mass-based liberation movement to a political party in charge of the modern state.

The ANC is finding it difficult to manage the transition. The party is being forced to transform from a rhetorical mass political movement to a modern political party. And the ANC in power is in charge of state resources – and responsible for those who might not even have voted for it. The pace and tenacity with which state bureaucracy intensified under Mbeki’s two terms as president made it increasingly uncomfortable for the party to live up to the challenges of the day. The ANC naturally felt left out of state affairs during Mbeki’s term, which widened the gap between the ANC and government. An opportunity existed for the emergence of a leadership that would bring government back under the party’s thumb. The floor was open to calls for populism, which rested on a listening leader who would not only respond more to the party’s demands on government, but was also expected to tame government and subject its functioning to the party’s whims.

It did not take much effort to brand the consolidation of state bureaucracy as a Thabo Mbeki project. The idea of ‘anyone but Mbeki’ emerged, notably mobilised by Cosatu and the SACP, the two formations that did not enjoy privilege in accessing the state machinery, including the ANC leadership in government. The practical implication of a stronger and solid bureaucracy in a modern democracy is that it usually reduces the influence of labour on state policy. Cosatu and the SACP, being the bastions of organised labour, were not given sufficient space during the consolidation of bureaucracy under Mbeki. So it was Cosatu and the SACP that attempted a reformulation of the anti-bureaucracy stance as an alternative to Mbeki’s leadership. Clumsily yet successfully, they mobilised the call for Zuma to emerge as a leader who would restore the position of the party in relation to the state – a leader who would effectively bring government back to the people.

Conveniently, Jacob Zuma was packaged as a victim of the excessive manipulation of state apparatus against an individual who connected with the people. Zuma was expected not to intensify the bureaucratisation of the state and its institutions, but to roll it back and customise it in a way that the broader ‘masses’, who brought him to power, would have a say in how government functions. The idea of an alternative gained momentum to the extent where it was only defined in relation to what it was not, and not what it actually entailed. It was a matter of a quick political machination to occupy the political space that was making itself readily available.

When Jacob Zuma emerged as an alternative to Mbeki, no efforts were made to demonstrate what he actually stood for. The focus was largely on what he would not be – and he would not be Mbeki. By then it was my strong belief that ‘if Jacob Zuma did not exist, the populists would have invented him’. His emergence as the alternative had little to do with personal acumen. Instead he was framed in an idealist manner.

The reality has been that the populist euphoria that brought Zuma to power could not sustain him once he reached the Union Buildings. As president, he had to implement certain decisions that affirmed state bureaucracy, just as Mbeki had done. The main difference between Zuma and Mbeki in relation to the bureaucracy is that Mbeki played a fundamental role in engineering the state bureaucracy and paid a price for this, while Zuma only had to maintain and strengthen the bureaucracy that was already in place, and to use it carefully to ensure his political survival.

While Zuma may differ with Mbeki in terms of rhetoric, the two men’s actions as statesmen and presidents follow the familiar bureaucratic trail constructed by Mbeki. The lesson from Zuma’s rise to power is that populism is good when it comes to replacing leaders, but not in sustaining leadership. Having come to power by surfing the populist wave, Zuma could not run the state by the same means. Further, by having to follow the bureaucracy of government, Zuma found himself in a situation where he could not claim to balance the relationship between the party and government.

At some point, too much concern with the party would render him an ineffective and unfocused president. On the other hand, too much focus on government affairs would result in the party drifting away and the development of a vacuum at party leadership level – the same vacuum that created an opening for Zuma as a populist candidate. He is the first president of the country who had to fight for a second term as the president of the ANC in government, because the ANC was getting accustomed to replacing leadership whimsically. But Zuma also reflected how leadership has learned to manipulate the internal processes of the party and the institutions of the state to remain in power, irrespective of how party members feel. If indeed Zuma was to be the man of the people, with an unassailable connection to the broader masses outside and inside his party, he would not have had to make a case for his retention as the president of the ANC during the party’s 2012 elective conference in Mangaung.

President Nelson Mandela did not have an interest in a second term either as party president or as president of the country. Had Mandela intended to continue for a second term, it would have been secured without a squabble within the ANC. President Thabo Mbeki also marched into his second term of the presidency without having to contest it. But Zuma had to make a case for the second term by getting internal party approval. His presidency came at a time when the ANC was constantly reviewing how it relates to government. This is not a stable environment, even though it is part of a working democracy. Jacob Zuma’s presidency has not been the most stable. Internal party squabbles have intensified since his triumph at Polokwane in 2007. Perhaps all this has much to do with South Africa’s political evolution, and Zuma’s leadership just happens to find itself within these developments. Let us consider how South African politics appears to be developing, as Zuma is an interesting frame of reference to understand this.

Zuma’s presidency is unfolding into an era that is identifiable and worthy of deep analysis. In some ways, justice has not been done to the man, because we are becoming a nation that perpetually seeks a scapegoat. Instead of confronting the evils of our society, we look for a way to normalise them, and thus ourselves, by pinning our failings on individuals. If Zuma is simply dubbed a ‘failed leader’, the nation will get to move on once he is gone, absolved and cleansed. In the eyes of some within the ANC, Mbeki was becoming a bad leader, and so the party, instead of looking inward, found in Mbeki a scapegoat for its own political shortcomings. So the ruling party unceremoniously removed him, and thereby cleansed itself of the sin it had committed by failing to transform into a modern political party.

As a society, it seems that we like to ‘manufacture’ leaders for our own convenience. And when things do not turn out the way we wanted them to, we simply demonise the leaders and blame them for all manner of uncomfortable socio-political developments. But usually the problem is much larger than one leader. In this case South Africa’s downward trajectory cannot be blamed on Zuma alone. He is, after all, just one man and part of a much bigger system. Maybe the Zuma years will help South Africans realise that deeply ingrained problems are not solved by getting rid of one leader and replacing him with another. South Africa’s problems are much bigger than Zuma. He has survived longer than most people thought possible, but one day he will go. And when he does, it certainly will not mean the end of our troubles.