Читать книгу The Ralph Nader and Family Cookbook - Ralph Nader - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

I grew up in Winsted, Connecticut, a small factory town nestled in the Litchfield Hills and lake country, surrounded by farms. It was an accepted practice that the fresh foods prepared for our meals were to be consumed without any whining or puckered facial expressions. My mother and father and their four children—two girls and two boys—all ate the same food. There were no food clashes; there was peace and time for what our parents wanted us to discuss, inform, and question regarding our schooling and readings.

However, one day my eight-year-old self rebelled. My mother Rose gave me a plate of fresh radishes, celery, and carrots.

“I don’t want that,” I said.

“Now, eat your food, it’s very good for you,” she replied.

“I don’t like it.”

“Ralph,” she urged, “these vegetables will make you stronger and a faster runner.” She nudged the dish closer to me.

“No, no, Mother, I don’t want to eat it.”

A triple rejection was very, very rare in our household. Mother did not believe in coerced or incentive-driven food consumption. She leaned over with her warm smile and asked: “Ralph, when you say I don’t like or I don’t want to eat, who is I?”

A little flustered, I blurted out, “I? It’s me, Ralph.”

“I’m not sure, son. Could it be your heart, your lungs, your liver, your kidneys that are saying no?”

By this time, I was reduced to sputtering noises.

She continued: “Ralph, I think I know who I might be.”

“Who?”

She smiled again and said, “I is your tongue, which you have turned against your brain. Now, eat so you grow up healthy.” Which, grudgingly, I began to do, looking forward to the tasty meal coming right after these “appetizers.”

That’s a glimpse of my mother’s way with food. To her, food—whether at breakfast, lunch, or supper—was a daily occasion for education, for finding out what was on our minds, for recounting traditions of food, culture, and kinship in Lebanon, where she and my father were born. Nutritious food was essential, we were told, to a healthy body and mind. Our mother cooked her delicious recipes from scratch. There were no processed foods on our table. Since the family owned an eatery, bakery, and delicatessen in the middle of town, called the Highland Arms Restaurant, my father would bring home whole grains, fresh fruits, and vegetables by the bushel. Mother’s homemade bread contrasted favorably in every way with what she called “the gummy, bleached white bread” sold in the stores. Never did hot dogs cross our plates, much less bologna or Spam. She would explain, “I don’t know what is in those hot dogs, and I don’t trust something I don’t know about.”

As much as she loved us and raised us to savor self-reliance, Mother never asked her young children—Shaf, Claire, Laura, and me—what we wanted to eat, because “young children don’t know what is good for them,” she told us later. “They don’t have to like what they eat; they just have to eat it.” We were expected to eat everything on our plates. “If children find out that not eating will bring them lots of attention, then they will frustrate their parents by making a scene again and again at the dinner table,” she said. But she knew that children also have an acute sense of fair play. “Parents should eat the same food as their children, no double standard.” I do not recall my father ever complaining about the food she served, other than occasionally asking that it be heated up more.

She believed “keeping it simple” and “everything in moderation” were two good guiding principles for our dinner table. It allowed her to prepare food more quickly. We were all expected to clean up afterward (though she washed the pots to her more rigorous standards).

Mother put all four children to work in our household. In the aromatic kitchen, that meant helping her with meal preparation and baking. I recall us kneading her bread dough, decorating her many ma’mools and ka’aks, while trying to keep up with her production. She would ask for help using a hand grinder to prepare the raw kibbe for baking and cooking. My sister Claire says that regularly assisting our mother taught her how to cook her recipes by osmosis. When Mother was away, I often made burghul, lentils, and other simple, delicious dishes during my high school years. I also liked making bran muffins. As a high school junior, I baked twenty-one muffins for Claire’s twenty-first birthday. She was a student at nearby Smith College at the time. My parents visited her that day and hand-delivered them to her.

Growing up in the 1930s and ’40s, our visiting friends would grimace as they watched us eat laban (now simply called yogurt), hummus, or baba ghanoush. Today, these delicacies have achieved widespread recognition among many Americans (although commercial yogurt has been made too sweet for my taste). Soups, stews, and salads, and a simple dessert such as rice pudding, a fruit dish, nuts, dates, or figs—these were common table items.

During holidays or birthdays, more elaborate entrées came from Mother’s busy kitchen. One of them was called sheikh al-mahshi (“the ‘king’ of stuffed food”), a baked eggplant stuffed with minced lamb, pine nuts, and onions, garnished with tomatoes and served on long-grain rice with a tossed salad. Every Friday we had baked fish with tarator sauce, reflective of a Christian tradition in Lebanon.

Given that our family restaurant served ice cream, we could have had it every day, but we did not. Mother believed that abundance could create problems, and that what is taken for granted becomes less appreciated. So maybe a dozen times a year we would go down to the restaurant and watch Father make ice cream. Father bought his milk for the ice cream from local dairies on hilltops so close by that we could hear the cows mooing through our windows. When the ice cream was ready, we would fill our bowls and lap it up happily. We appreciated it that much more since it wasn’t an everyday occurrence.

Father also played an important role in our food life. He specialized in bringing us bushels of fresh apples, oranges, peaches, and plums. Pears we harvested from the faithful old tree in our backyard, twenty feet from our kitchen. And his favorite fruit—grapes of all kinds. My father liked to stew Granny Smith apples, cutting them into bite-size chunks. He wasn’t looking to make applesauce, and he succeeded admirably with close attentiveness. In a little saucepan, he cooked the morning oatmeal with the same practice, getting it to a creamy consistency.

Seven days a week, the Highland Arms served American food. In those days, there were few ethnic restaurants aside from Italian or Chinese. Pizza hadn’t even made it big yet. Patrons just had little taste or patience for new kinds of food. They stayed in a menu routine so predictable that, as a young man working in our restaurant, I could give the cook the order as soon as a regular customer sat down. Now there are far more food choices in restaurants of all ethnic backgrounds (including twenty-five Ethiopian restaurants in the Washington, DC, area alone).

The menus at the restaurant affected our eating at home mostly at breakfast—oatmeal, pastries, poached eggs, and jam. But by and large, the cuisines of America and Lebanon were worlds apart and my sisters, brother, and I greatly preferred the home-cooked meals full of garlic, mint, and the spices of our ancestors.

Of course, there were collateral benefits. Mother knew that at the kitchen table she had our undivided attention. When we came home from our nearby schools for lunch, she would relate historic sagas, like the tales of Joan of Arc. She never read to us, preferring to rely on her memory to tell stories and recite Arabic poetry, watching the expressions on our faces closely. Coming from a vibrant oral tradition in Lebanon, she had an endless treasure trove of recollections. So much so that when we were restless or mischievous, she, along with Dad, would reprimand or chide us with proverbs. No “shut up or you’ll be sorry”; instead, the wisdom of the ages wrapped up in a concise Arabic proverb disciplined and impressed us far more. As with “jokes are to words as salt is to taste,” meaning: don’t overdo the silliness.

At the dinner table, my mother would gently ask us what we had learned from our teachers that day at school. Clearly, small talk and gossip were not high on her agenda, though she knew those had their place.

Mother did not believe in regular snacks between meals. Occasionally, she liked to surprise us and would give us some labneh with olive oil, tucked inside whole wheat pita bread, to take to school.

Sometime in the 1970s, having seemingly run out of criticism of my consumer protection work, the Wall Street Journal devoted an entire editorial to how puritanical my mother was, forcing chickpea snacks on us instead of, presumably, candy. The Journal was particularly incensed at my mother quietly scraping the sugary frosting off birthday cakes once we had blown out the candles—a practice that had become a family joke.

Mother reacted with amusement. Cakes had plenty of sweetness, she would say, without loading up on frosting that was pure sugar. She knew that meals were about much more than food. For Mother, the family table was a mosaic of sights, scents, and tastes, of talking, teaching, and teasing, of health, culture, stimulation, and delight. For Dad, it was a time to ask us challenging questions to sharpen our minds and our independent thinking. Such as: Do the great leaders make the changes in history or do they reflect the rising pressures from people at any given time? Is it better to buy from a local family-owned business than a large chain store? When can a revolution be called a success? What were you taught in school that you found out not to be true?

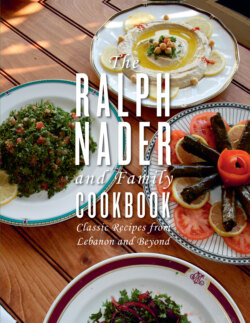

I had several inspirations for making this cookbook. One goes back many years—people always asking me what I eat, prompted in part by my work on food safety laws. Another was the remarkable response to the 1991 collection of recipes and wisdom—“food for thought”—that my parents compiled in the volume It Happened in the Kitchen, which was featured twice on Phil Donahue’s popular TV program. Their book was a major source for this one. Finally, the growing popularity of Arab cuisine, backed by the growing scientific research into nutrition, has broadened the audience and market for what was once seen as an “exotic” menu. Diet is viewed by both consumers and physicians as more and more significant in an individual’s weight, energy level, and overall health. Medical schools, which traditionally haven’t featured nutrition very prominently in their curricula, are coming around to this realization.

As is reflected in the recipes chosen for this book, we were mostly raised with Arab cuisine—more specifically the food of the people who lived in the mountains of Lebanon. Today’s nutritionists have pronounced this Mediterranean diet to be just about the healthiest diet in the world. It is heavy with varieties of vegetables, fruits, grains, nuts, spices, lean but not too much red meat, mostly lamb. The noted national dish of Lebanon—kibbe—often takes center stage on the table.

Two of the recipes in this book were contributed by Chef George Noujaim, a Lebanese immigrant who runs Noujaim’s Bistro and a catering service in my family’s hometown of Winsted. Connecticut Magazine named Noujaim’s the best Mediterranean restaurant in the state.

Many of the ingredients for these recipes can be found these days in general supermarkets, as well as in health food stores and specialty Mediterranean grocery stores. The recipes are healthy and are reasonably low in fat, salt, and sugar (the latter given leeway in the desserts). The dishes are easy to prepare, with only a few exceptions.

For sure, much of our upbringing happened in our comfortable kitchen—tucked between two pantries at our family table. That is why the recipes in this book evoke memories of their broader contexts and celebrate the fortune my siblings and I had of being born to such wonderful parents.