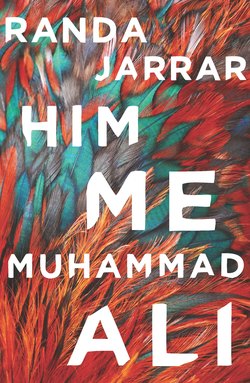

Читать книгу Him, Me, Muhammad Ali - Randa Jarrar - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE LUNATICS’ ECLIPSE

The neighborhood got its first dose of Qamar the summer of her ninth birthday, when she sat on the rooftop of her Alexandria apartment building for ten days and waited for the moon to come down. She did it for her neighbor Metwalli; he promised he’d be hers forever if she only brought him the moon. Metwalli was twenty-four and had no idea that Qamar would take his pledge to heart.

The first night on the roof, Qamar sat on a long chair with a rope in her hands. The People began to wonder, and when midnight came and she was still there, they informed the bawab—the super—and asked him to go check on her. Too lazy to climb the nine stories, he shouted up from his post at the front entrance of the building, “What’s with you, Qamar?”

“I want the moon,” she yelled.

A collective sigh was broadcast from the audience that now gathered in the street. “The moon’s expensive,” the People yelled back at her. “It costs ten nights, ten whole wakeful nights . . . and you can’t nod off, not even for a second.”

Qamar stayed up the ten whole nights, and the moon was descending, everyone agreed that it was. Qamar developed dark crescents under her eyes and her hair was dreading. On the tenth night, the moon vanished, but the People never agreed on how. Some said that Qamar nodded off and the moon shot back up into the vastness of sky, so high no one could see it anymore. Qamar said she only fell asleep for an instant and when she opened her eyes, the moon was gone, and she insisted that Zeinab, the evil neighbor girl who had had her eye on Metwalli for weeks, filched the moon during that short instant. How else could one explain what happened next? Metwalli fell in love with Zeinab, and ten years later, they lived in a flat on San Stefano Street with six children. Metwalli was Zeinab’s forever, and Qamar was a stranger.

It made a small sidebar in all the papers: Al-Ahram, Al-Akhbar, and even Al-Sharq al-Awsat. That was how Hilal knew of Qamar; he’d read the story in Al-Ahram ten years before. Hilal himself had appeared in the paper twice. The first time for placing number one nationwide in the secondary-school final exams and the second for turning down the president’s offer of sending him to London for free medical training as a cardiologist. Hilal wrote to the President: “Sir, I have no interest in hearts or in how to mend them. Can you send me to Houston?” You see, Hilal had been trying to figure out a way to get to the moon since he was four years old. His father, a fisherman in Alexandria’s east quay, once caught Hilal dangling his feet outside the boat and casting a net over the moon’s reflection. Much later, Hilal heard that men could walk on the moon’s surface and when he looked into it (he took the tram to the American embassy, the Russian embassy, and the visa office), he realized that jumping to the moon would be more realistic than obtaining a visa and traveling to Houston for astronaut training. Here’s what the President had to say about NASA instruction: “Son, our country has no interest in reaching the moon. However, we do need a bright young man like you in our nuclear-weapons development facility.”

You might wonder why Qamar’s parents let their child sit on the roof for ten nights in a row, and for a boy. You might think Egyptian parents don’t let their little girls get away with things like that, and you’d be right. But Qamar’s parents were different; they were actors in the Theatre d’Alexandrie. Her mother was Sophia, and her father was Farid Hafez. You may have heard of their summertime performances at the Corniche Theatre—the pink, hieroglyphed, open-air venue resembling a conch shell. Sophia and Farid performed musical comedies on that stage, their only child watching from behind the velvet curtain every night. When she was five, she told them she wanted to dance, but she needed credibility as a performer, so they enrolled her at the Conservatoire for ballet lessons. By her thirteenth birthday, she was one of Egypt’s top ballerinas, the Russian-allied government sending her to St. Petersburg for exclusive performances.

When Qamar was fifteen, her parents were run over by a van in St. Petersburg as they were crossing the street to watch her dance at the theater. The van’s passengers, sticking their heads out of the windows and peering into monoculars, distracted the heavy-footed driver. Looking up into the sky, he saw the cause of their excitement: a lunar eclipse. Her parents were killed instantly.

Now, if she hadn’t been a ballerina, she wouldn’t have gone to St. Petersburg. If she hadn’t gone to St. Petersburg, her parents would have never crossed that cursed street. If her performance had been on a different night, the driver would not have been distracted. If, many years ago, Dulles hadn’t thought Nasser was bluffing, Egypt would never have found an ally in Russia, and her performance may have been held in Washington, where van drivers rarely hold romantic sentiments about the moon or any other heavenly object.

Ever heard of anyone dying of a split? She hadn’t and so immediately began working as a tightrope walker for the Cirque de la Lune, a French circus based in Alexandria. Their tent was attached to the St. Mark School for Boys. You could see her walking the big brown bears in the early mornings, berating them for laziness. They always moved a bit faster for her. She wore her tightrope-walking suit: a shiny green leotard and a lime-green tutu speckled with tiny silver stars. Her tights were sheer gray, her feet bound in pink ballet slippers. On leashes, she would walk all nine bears in circles around the circus courtyard, en pointe.

The first time Hilal glimpsed Qamar, he was riding the dirty street-tram and staring out the broken window. He caught the same tram to the nuclear-development plant downtown, and one morning, he saw her leading the bears. To him she resembled the sun of an entire cosmos. He felt as though his spirit was spilling out of the speeding tram’s window and for weeks tried to work up the courage to get off at the St. Mark station and visit her. He didn’t realize then that she was the nine-year-old featured in the newspaper.

Later, Hilal rummaged through his drawer for his journal and found the yellowed paper with the old headline: “Girl Makes Moon Disappear.” He decided to use part of his weekly salary to go to the Cirque de la Lune and see Qamar’s high-wire act in person.

Qamar had discovered, forty-eight hours after her parents’ death, that she must marry Omar, a family friend who would take over responsibility for her. This final blow had sickened her so much that she decided to present her show without a safety net. At first this made the circus ringleader Laurent’s stomach churn, but eventually it brought the show good publicity, so he let her do it. She walked the wire en pointe, performing flips and splits, pliés and twirls, all the while hoping to fall and break her neck. She never did. Suspecting it would take riskier moves for her death wish to come true, she incorporated a pigeon (a vulture) and a cat (a tiger) into her act. Hilal watched her from the front row, his heart drumming like a tattered tabla.

After the show, he followed her home. She knew he was trailing her, so she walked through strangers’ courtyards, under banana trees and their huge leaves, in and out of buildings, and hid behind jasmine-trellised walls, her heart beating hard until she lost him.

Once home, she sat out in the balcony and soaked her bloodied toes in ice water. The residence, over seventy years old, had balconies, each covered by a mashrabiyya. From her balcony, she could see Cleopatra Beach and a broken moon in the water, the obelisk in the middle of the nearby square—a leftover piece of history. Archaeologists had observed it the previous summer, and said the ancients placed it strategically so that it lined up with a constellation, like a finger pointing to the heavens.

Qamar’s bed was on the balcony; she moved there after her parents died. She began sleeping in a black nightgown, mourning them in her dreams.

Hilal believed she had the courage he lacked. That was why he thought he loved her. He would never be able to walk on the moon, but he formulated a plan. The President let him dabble with anything as long as it didn’t involve explosions. And that was fine with Hilal: his rocket didn’t need to explode.

On the night of the Mouled—the celebration of the Prophet’s birthday—Qamar, depressed, with only a few weeks of freedom remaining before her wedding, went out to join the festivities. That night, all of Alexandria was a circus; there were colorful celebrations on every major street. Sufi dancers in white robes twirled around in red-and-white calligraphy-covered tents—twelve dancers in all, weaving around themselves and in a circle, perfectly synchronized, like the planets.

Qamar remembered one Mouled in particular: her father took her to the pastry shop where they bought arouset el-Mouled, the traditional doll of the Mouled. The doll was made entirely of bright pink sugar and Qamar used to think that it looked like a ballerina. She had refused to eat her doll and kept it on her bookshelf. The next morning, she was horrified to find only part of the doll’s dress left, and even that was covered in small black ants busily chewing at its pretty pink skin. Qamar decided not to buy a Mouled doll this year. She visited the many tents and walked back and forth on the Corniche, finally stopping at the eastern harbor.

That was where Hilal saw her. He almost didn’t recognize her; she was wearing jeans, dirty sneakers, and two uneven braids that were partially covered by a deep-blue kerchief. He stood next to her and said that he used to fish the face of the moon. Then he asked if she’d been the nine-year-old girl from the newspapers. “That bitch Zeinab,” she said, and he got to hear the part of the story the newspapers didn’t print.

They walked along the ocean road, Qamar half-wishing Omar would see her with Hilal, assume she was a slut, and break off the engagement. Arriving at her building, they stood in front of the café at the bottom floor. Several older men sat out front, smoking honeyed tobacco out of old sheeshas and swapping stories. Hilal pointed at a small black-and-white television in the corner. When Qamar turned to the flickering screen, she saw Michael Jackson onstage wearing shiny gloves and doing the moonwalk.

“Kul sanna winti tayeba,” he said. “Merry Mouled.” He gave her a pink Mouled doll and she accepted it, figuring her ant story would be too complicated to tell.

Qamar went home, sat on the balcony, and ate the pink sugar doll. She began with the doll’s feet, then the legs, then devoured the torso in less than thirty seconds. The head took a little longer. Too full to eat the arms, Qamar flung them onto her nightstand and almost passed into a sugar coma. She got up and took all her clothes off, then looked out of the mashrabiyya and onto the street, where Hilal stood by the obelisk. She wondered if he could see her and reached over to her black nightgown, pausing a moment before slipping it on. Then she tumbled into bed and fell asleep at once.

Hilal did see her—the brown skin behind the wooden lattice partition. The moon shone its borrowed light through the screen and cast intricate shadows across her breasts, her belly, her legs. He felt as though he’d stolen something sweet, and after she disappeared, he walked home, feet bouncing off the asphalt.

The next day, the doll’s arms, intact, shone pink. Not an ant in sight.

Hilal began attending the Cirque de la Lune often enough to get in free. He was unaware that Qamar’s wedding day was fast approaching, and that this was the reason she now used a unicycle with two high wires in her act, jumping from one to the other. She still refused a safety net. One evening after the show, Hilal asked if she’d like to go to the Montazah—the public park at the northeast end of Alexandria that used to be King Farouk’s summer palace—popular romantic hangout.

“So you can tell me about the deer that used to wander around there and we can listen to how nice the waves crash and you’ll try to kiss me? Ah, no,” she said nervously in one breath.

“What would you rather do?” Hilal said, looking over at an old man fanning corn over coals on a straw crate.

“I almost broke my neck, and I’m still in ballet slippers. I’ll give you one guess.”

“You want to go home and go to sleep. I understand. Good night,” he said, flagging down an orange-and-black taxi.

Qamar made a loud buzzer sound. “Wrong. You guessed wrong. I want ice cream. I want two scoops. On a cone.” He laughed and said something about ballerinas not being allowed to eat more than three grapes a day. “That’s why I quit,” she lied.

The cab took them to Sultana Sweets. Hilal ordered one scoop of vanilla on a cone, and Qamar said the scoop looked like the night’s full moon.

They sat on the bridge. He stuck his tongue out to lick the full moon, but it fell off the cone and onto the ground. “Very coordinated,” she said. “I’d like to see you walk the rope sometime.” The bridge stretched over Desert Highway 1, the third most fatal motorway in the country. They watched the cars go by, trucks brushing the soles of their shoes.

“I have a rocket,” he told her. “Built it myself. Wanna go for a ride with me?”

“Very funny,” she said.

He said he was serious. That he wanted to go to the moon with her. That she’d made the mistake, when she was nine, of waiting for it to come to her.

“The moon is at 325 San Stefano Street. Metwalli’s got it. I’m getting married next week, did you know that?” She said this without looking up from her ice cream. The cars zoomed by beneath them, and Hilal wanted to jump, to make a pretty design on the asphalt below.

“There’s no reason why two people need to know each other’s every flaw before they get married,” she said in between licks. “No mathematical law or theorem for falling in love. It isn’t like the distance to the moon. It’s much less than that, and more doable.”

The din of passing traffic made it difficult for him to hear her clearly. “Are you saying you love me?” he said.

She hit her forehead with the palm of her hand. “I’m saying I’m getting married next week. You’re invited.”

The day of the wedding, Hilal completed his rocket and hauled it out to the square by Qamar’s house. It was Ramadan, and people were breaking their fasts indoors, so virtually no one saw him. If they did, they rushed home and told their wives: “Tsaddai ya sitt—can you believe it, woman? I just saw a white rocket on the back of a truck. I’m that damn hungry.”

The wedding was at home; her uncles and aunts, cousins and grandparents, and future in-laws arrived early. They danced and sang and ate, then waited for the ma’zun to come and officially marry her to Omar, the man they had chosen.

Qamar looked at Omar, who stared hungrily at her upon his arrival. She tried to crack a smile. His eyes bored into hers, and her arms went numb. Qamar realized then that this man made her feel like a Mouled doll, as if there were millions of ants chewing her body from the inside out. Wanting some air, she reached over to the window and saw Hilal standing near the obelisk. Then, beside it, another “obelisk.” She yelled, “Ah, the man wasn’t kidding.”

“Who?” Omar said. He panicked at the mention of another man.

She stood up and walked toward the balcony.

She climbed over the railings. Her family stopped eating, and all eyes were fixed on Qamar as she jumped down to the yellow clothesline. Hilal saw her then, and a bright smile stretched across his dark face like jet stream in a clear sky.

He started the rocket engine.

She walked the line all the way to the end and jumped onto a lower clothesline. The People in the street looked up at her and heaved a collective “here she goes again.” They informed the bawab, but he was too afraid to climb any clotheslines, so he yelled from his post at the front of the building, “What’s with you, Qamar?”

“I want the moon,” she yelled back. The People began to say something, but Qamar did a backflip onto another line dotted with a fat woman’s underwear, and told them, “And I don’t need your advice this time.”