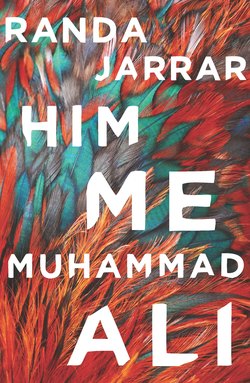

Читать книгу Him, Me, Muhammad Ali - Randa Jarrar - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBUILDING GIRLS

They come to Egypt in the summer; they come in their rented cars and bring their families and buy umbrellas and beach chairs; they bring swimsuits and towels and creams for their skin so it won’t burn. They make me laugh. They come in June, sometimes as late as July, and stay until September, when their children return to school and they return to their jobs. It’s hard for me to imagine leaving work for an entire season; I suppose when no one is here from September to June, that is my small vacation. On my vacation I still have to wash walls and plant plants and paint and water and clean. On top of all that I have Shadia to take care of, my little Shadia who looks just like her father, the bastard. Him, I have a permanent vacation from. Thank the lord!

I was born here, at the bottom of the building on Seventh Street, in this small beach town, at the lower tip of the Middle Sea, between the cities of Alexandria and Abu Qir. My mother and father have been married thirty-five years; in that time my mother lost many of her teeth, lost her small figure and some of her hair, and my father remains almost exactly the same, skin black like the street where the summer children play soccer, teeth white and gleaming, with occasional cavities, so they look like tiny soccer balls. He runs errands for the women whose husbands stayed in the city, or for the widows, or for those whose husbands are lazy. I sometimes see the women blush when Father talks to them, because he is unbearably handsome. I look a lot like him, except my skin is black and I am a woman, so I am not considered unbearably beautiful.

I have been working for my parents and for the owners of the building all my life—thirty-four years, if you want an exact number. I took a break when I married the devil, Shadia’s father, whose name I cannot bear to utter. I was never in love with him; he was twelve years my senior and Mother thought he’d make a good match when she heard from my cousin that he was looking for a wife. He lied and stole and broke my heart, which wasn’t his to break. And when he put his hands on me, I’d shudder. I hated his sex, his skin, and his smell. He had a nasty temper and struck my face and kicked my bottom more often than I cared for, and when I went home, dragging Shadia behind me, Mother spat on me and told me to go home to my husband. I cried and told her what happened, but she didn’t blink. Father intervened on my behalf and declared that his house was my house, and Mother slapped her own cheeks and wailed. I smiled with relief, entering the little bottom-floor apartment, the fabric on all its walls scented with every meal I had ever prepared or eaten there.

My real bosses are the families of this four-story building. In my building are two apartments on each floor—one on the left, another on the right—and four floors. I call the first floor the mirror floor: the family on the left has three daughters and one son, and the family on the right has three sons and one daughter. You’d think they would have naturally paired off after spending every summer together, but they never did. The boys played soccer every day and the girls played alone or split off into age groups. Their mothers adored one another and the husbands despised each other—one was an intellectual and spent his summers at the building reading on the balcony, and the other spent his summers buying watermelons and watching soccer games on a television he wheeled out to the balcony every night. I loved observing them from the street, the intellectual flipping his pages after each burst of applause coming from the watermelon-lover’s screen.

The owners of the second floor’s left unit live downtown and rent their apartment out to honeymooners. I like to watch the new brides stroll down the street awkwardly, in that newly deflowered way, their gait hesitant and their palms pressed into their husbands’. On the other side lives Madame Manaal; she has lived there for thirty-four years. When she moved in, my mother was pregnant with me, and I floated inside her belly, squinting in its darkness. My father says Madame Manaal moved in after the deaths of her husband and her eldest son; she asked my father, upon her arrival, to shutter all her windows, and he complied. When I was a child, Madame called me up to give me her grocery list; in contrast with the brightness of the street, the blackness that cloaked her greeted me like a chasm on the other side of the doorframe. Sometimes, when I am feeling strange, I imagine Madame Manaal is my old self, still floating in my mother’s belly.

The third-floor apartments were joined together when their owners, who live in the Arabian Gulf, knocked down the wall in the middle (I was a witness to this marriage and covered my ears when I heard the ceremony commence). They visit every three years and the rest of the time their furniture is covered in white sheets. Sometimes, I go up there and listen to their records or take naps on their beds. Sometimes, I imagine the white sheets are hiding people, an idea that arouses me, and I practice my secret habit on the biggest bed.

The fourth-floor apartments are also frequently empty. The one on the left belongs to an elderly man, an ex-officer who took part in the 1952 revolution. When he visits he brings all his grandchildren and his daughters. He wears a small hat and sandals and goes for walks very early in the morning, his hands daintily hanging at his sides. I try to imagine him holding a rifle in those hands or pulling a string on a cannon, but I cannot.

The apartment on the right is where Perihan, my summer best friend, used to stay; she visited the building with her family every year for fifteen years; we used to play together in the dump next door. Now, my family tends to chickens there. Back then it was filled with trash, and Perihan and I would dig through it to find shiny tins and pots which we tapped with sticks and made into drums. Perihan wore her dresses, shiny pink and silver things, and crimpled hats. I wore the same nighties I slept in and put big perfumed flowers in my hair. She liked that my hats were from nature, and that I didn’t have to change just because the sky had turned from night to light or vice versa, and as the summers progressed, she’d become less a rich girl on the top floor of the building and more one of our sisters at the bottom of it; she wore her galabiyya and her plastic torn-up sandals, and we wreathed flowers, pink and fat, into strands of her brown hair which shone red in the sun.

When we swam she wore a swimsuit and I wore my clothes; I didn’t understand why you had to wear special clothes just for the water which really didn’t care how dressed up you were when you came to meet it. Out of modesty, too, I have never revealed my arms or legs outside my home.

Although she hasn’t visited in almost ten years, whenever the cars pull into our street and new people arrive, I sometimes imagine that the little princesses stepping out of the back seats are Perihan, even though she must be thirty by now. A gray Peugeot pulled up this June, and a Perihan impostor, eight years old and wearing an American outfit, appeared. I wanted to rush to her in glee, my old body slowly catching up with my excitement. I heard someone call my name, lilting and pealing its letters like a brand-new bicycle bell. In time, I realized the little Peri was her daughter, with the real Perihan in tow.

At first, we exchanged kisses and hugs, and my father and mother came to greet her. Shadia stayed by my candy-and-chips stand outside the building; she was shy and still. Perihan’s daughter, Anna, went to Shadia; the little girl spoke not a word of Arabic but was charading wildly and making Shadia laugh. They played together; Shadia showed her our home, and Perihan and I took their suitcases up to the apartment. Halfway up, on the third floor, Perihan’s breath was running ahead of her and she had to slow down. We talked for a while; I told her about Shadia’s father, the ass, and she told me about her daughter’s father, also an ass. I asked her what she needed from the market, and she turned red and said she could shop for herself. “Oh, you’re tired,” I said. “Let me. I have a bike now. I like riding it.” She reluctantly agreed and gave me some money, and I was off to buy her groceries, just like I did for her mother twenty years ago.

I like being at the market; people push past you and men wink. I love watching the summer crowds and their dealings. Girls wear tight denim and let their straightened hair spill across their shoulders. (My hair is always in a bun or under a kerchief.) Men follow them and hurl sweet praise their way, and the girls pretend to hate it or not to hear. The shops stand close to each other, nothing but thin walls to separate them: cheese here, bread there, toys here, mattresses there, dresses here, kerchiefs there, books here, books there. A nasty-smelling fish shop sits at one end of the market and a shiny silver jeweler on the other: in that sense, even the market has a top and a bottom floor. I rode by the bookseller’s and quickly scanned the covers and titles; all books about a man who goes far away for school, comes back to the homeland, and decides that this is where he belongs. In winter, I read them out of boredom and, to be completely honest, I prefer planting flowers or watering the banana tree or even being sweet-talked by toothless men to reading these kinds of books. After I filled my cloth sack with cheese, yogurt, eggs, tea, mint, toilet paper, a newspaper, and bread, I mounted my bike and rode off, the smell from the fish shop at the opposite side of the market wafting over me. The smell was like Shadia’s father, foul and persistent, so I pedaled my bike faster.

When I arrived at Perihan’s, she had all the windows closed and the air conditioner in the corner humming. She asked me if the mosquito truck had gone by yet, and I said it hadn’t, so we emptied her suitcase together. I asked about her daughter Anna’s father; he was American and they were divorced. Anna was darker-skinned than Perihan, and Perihan told me that not all Americans were blonde and white. I was confused and asked if she was lying, and she swore on the holy book she was not. “Anna’s father was brown-skinned, like an Egyptian,” she winked and I laughed. We made tea and she asked me to sit out on the balcony and drink with her but she wouldn’t let Anna come out with us. She said the mosquito truck emitted fumes that were cancerous and she didn’t want to expose Anna. I nodded silently and drank my tea, even though it now felt like mud on my tongue and in my throat. I wanted to ask if she’d forgotten how we used to ride on our bicycles behind the truck at night, and inhale the big white cloud until we felt like we were in the sky itself. I wanted to ask if she now thought I would get cancer, or if Shadia or my father or all of us that were left behind here in the beach town would get it. When the truck pulled up she covered her nose like a snob and I couldn’t bear it, so I pretended I had to go bathe Shadia, dumped the contents of my teacup and went down the stairs two steps at a time. That night, the image of Perihan with her nose pinched burned through my eyelids. I rubbed my eyes and turned to my side.

The girls played in the street or fed the chickens in the dump, and Peri sat on her balcony and read or watched the beach. I asked her why she was in Egypt, and she told me she was here doing research for her PhD. I wasn’t sure how sunning herself on a balcony would get her a doctorate, but I said nothing. Sometimes she came down and sat next to me where the entrance of the building met the street. I crouched beside my candy-and-chips stand, my soda cooler and my umbrella, and whenever someone walked by, we would hassle them to buy something. Perihan was the best hustler; she’d tell people they looked parched or pick on the skinny summer-girls and try to get them to buy chips. She was a great saleslady and I told her that. When business was slow we walked around the building and I showed her my plants, her mouth open in amazement the whole time. She kept repeating, “You planted this tree? These flowers? These herbs?” She loved the garden, and some evenings after the dusk prayer, she asked if she could water too. I always said yes and watched as she leapt around the garden with the water hose, completely content.

One morning, after she’d come with me to the market and the girls had begged us for countless toys, she asked if Shadia’s father ever visited her. “Him?” I feigned disgust and told her he hadn’t seen her in years. “Abu Anna visits,” she said, after a long pause.

“When?” I wanted to know.

“On Wednesdays between five and eight, and every other Saturday,” she said. I laughed hard then, because Perihan could be so funny when she wanted to be, and her specific brand of humor was based on giving exact measurements for things that cannot be measured. She laughed with me, but swore it was true.

The girls played in the dump by the building, and declined whenever the girls from the mirror floor tried to play with them. When Peri and I were their age, we used to accept these offers only to regret them later: someone bossed us around or stole our treasures or flounced around us and made us cry. It was as though our daughters had learned that lesson through us, and seeing this made me happy.

I was convinced that we should go to the bazaar, and I rounded up the girls and we all walked out to the tent by the carnival. I love the flea market; it comes through every July, rows and rows of rings and rocks and skirts and necklaces, dozens of vendors. I like the way everything looks, colorful and loud, like a circus. Perihan bought some dresses and a ring, and I pawed a pair of earrings until she made me try them on. They were round and big and made of brass with fake garnets in them, and in the mirror—with the carnival tent behind me and the earrings hanging by my face—I looked like someone else entirely. It felt good to pretend to be someone else, so I asked the Malaysian man at the counter how much they were and haggled until he agreed to half his initial price. Perihan insisted on paying. I thought that was kind so I let her, and afterwards she slapped my palm and giggled and told me I should teach negotiations at universities around the world.

Sometimes, Perihan’s friends visited from downtown and she sat with them on the balcony far into the night, telling them stories in Arabic and English. It was understood that I would not join in these gatherings, the same way a person does not bring a car into their house. They all giggled and drank Stella and smoked cigarettes, and Mother shook her head in their direction because she did not approve. In the morning, which began at around 2:00 P.M. for them, they walked to the shore carrying beach chairs and umbrellas. By then I would have already shopped for the first and second floors, watered the plants, done the wash, cooked for my family, and cleaned the building’s entrance with rags. I jealously watched Peri and her friends walk down the street, then went to my garden and sat in the shade and daydreamed. The honeymooning women shouted down at me from the third- and fourth-floor balconies, and I ran up for their grocery lists. They paid the total and usually tipped me around 20 percent for the delivery. At the end of the summer they’d also give me a bulk tip. These tips and end-of-summer gifts provided enough money to tide me over until the next summer.

Whenever I thought of winter, I pictured it dark and long like night, like Madame Manaal’s apartment, or my eyes when I close them against the light. I dreaded the town’s emptiness, how residents would leave like ants being flung from a vast, billowing blanket. I put the wash on the clothesline, pants and undergarments and shirts and shawls, and as I fastened them with wooden pegs to the bright-yellow line, I wondered about love, if I would ever be blessed with it, or ever be married again. I wanted that, but I told Mother and everyone else that I didn’t, pretended that I hated men and their wiles, and that I wanted to be alone forever.

Perihan confided in me one day at dusk, as we sat on her balcony and sipped at our mint tea, that she too was lonely and wanted to be in love. She asked me if I thought we were cursed, and I spat in my chest and said, “Let’s hope to God we’re not.” She asked if I knew of someone who might break the spell if there was one, and I told her I did. Perihan leaned into the edge of her seat, her back straightening, and said, “When can we go see her?” She smoothed her bangs and I said, “Well, not now. . . . Maybe tomorrow.”

The next day we took the bus out to Abu Qir. Perihan gawked at the ponies and carts that passed by. I nudged her with my shoulder and she stifled her giggles. We walked between two buildings into a cobbled sand-brown hallway that was windy and salty, the blue of the ocean ahead a rectangular marine box. We found the woman’s door and knocked. She sent her girl to answer it, and the servant stared at the two of us—an odd pairing in differing ensembles, she must have thought: one crinkled, one starched—then ushered us in. We described our woes to the woman, who was the size of Shadia but eighty years old, her neck an accordion. The servant made cups of coffee; we drank them and the old lady told us to push our thumbs into the base of the demitasses. We did, and passed the cups back. She read Perihan’s cup first: Perihan was a fool in love, she said, but soon, she would find a man. She didn’t have to pretend to be anyone else; she just had to be the way she was and a wonderful husband would appear. He’d be tall and have a goatee. It would happen within the next three months. Perihan nodded silently. I was confused as to why she wasn’t excited. Maybe she didn’t believe in fortunes?

Then the woman labored over my cup, huffing and tut-tutting. She turned the cup over and over in her hand, and finally she exhaled loudly and said, “There is no power nor strength without God. My girl, I see nothing in your cup but darkness, long darkness with small bursts of light once a year. I am sorry, daughter.” I nodded and stood up. Perihan looked at the old woman with hateful eyes, then blurted out, “Why did you say that to her? We were both going to pay you the same exact amount. You’re a fraud. Besides, I don’t like men.” I grasped her by the arm to silence her, pulled her off the couch, and we left.

By the time we walked home from the bus, the sun was setting, and the girls were sitting by Mother at the edge of the dump, eating grilled ears of corn and grinning. From where we stood, they looked just like we used to. Perihan said goodnight and told Anna to go up to sleep when she was done. Anna was confused, so Perihan said it in English, then Anna argued, negotiating a longer stay, but Perihan wouldn’t budge.

After Anna went up and Shadia came in for her bath, I thought about the old lady of Abu Qir, about what she had said about my darkness. I looked around my apartment: ever since I could remember, our walls have been covered in rugs, rugs in red, orange, blue, and green. Our house is colorful and serene; Mother says it reminds her of home down south, and Father, a wise man who likes to maintain peace, agrees with her as he does on everything. Outside the house are my flowers and plants and upstairs, in the homes of the people for whom I work, the walls are white and everything is bleak.

After Shadia slept, I watched the street and the sky. A woman’s voice floated down from her balcony. “Mother of Shadia! Mother of Shadia!” Perihan was the only person who called me that. Normally, I hate when summer folks want me to do something for them this late in the evening, but for Perihan, I was willing to let go of my annoyance. I climbed the stairs and found her on the third floor. “Do you smoke?” she asked. “Bongo, I mean?” I gasped, then laughed. I had never smoked drugs before but I couldn’t imagine anyone else I’d want to share them with. “Yes,” I said, and she took a long white cigarette out of her pocket. I whispered that she was nuts and to put it back in her pocket; we had to go to the roof if we wanted to do something that illicit. She obliged and followed me up.

We climbed the ladder onto the roof and watched as the wash fluttered in the breeze. She lit her cigarette, took a drag, and passed it along to me. I smoked and, halfway through, got the giggles. She laughed too, and we watched the beach and the street below. My mind felt light, and my body relaxed. We told each other funny stories, but an hour later, Perihan began to get morose. “I hate not being a little girl,” she said. “When I was little I wore a nightie in the street and no one looked at me. No one whistled at me. I felt invisible and happy. I had no money and I was happy. Look at you. You still wear what you used to wear. You live the same life you’ve always lived. You have a home here, and you always will. You raise Shadia without her father, but not alone; your mother and your sisters and all the neighborhood helps. I envy you.”

I couldn’t believe what she was saying. No one had ever told me they envied me. And why would Perihan, the light-skinned beauty who lives in America and who’s been on an airplane, envy me?

“That’s silly,” I said. “No one helps me. I was punished for leaving Shadia’s father. My mother still won’t look me in the eye. I’m considered worse than a widow, and my honor is constantly in question, just because I’ve had . . . sex.” I was high. “Besides,” I giggled, “it should be the other way around.” I was not ready to be morose. “I should envy you. You’re getting the man with the goatee.”

We both laughed at this, big laughs that stole away our breath, cascading giggles and tears. Perihan said, “Listen, I know I’m paranoid right now, but listen, I think she switched our fortunes.”

“No.” I slapped her arm.

“Yes, yes, yes. In the next three months you will meet your man. My life is dark and miserable except for the summers, when I’m not teaching and I can travel. Yours was my fortune. Trust me.”

I laughed and blushed and told her I hoped we both could get love. She smiled and said, “From your lips to the heavens.” Then she stared at my lips for a long time and I felt a warmth spread through me.

“Do you want to see the phantom apartment?” I said, and she squealed and nodded. We pushed the timed light-switch and ran down as quietly as possible to the third floor. She held on to my dress, laughing. Inside, she gawked at the white sheets and marble floors, sat down and ran her hand against their surface.

“I saw them install this floor,” I said. “Burly men carried the slabs up on their shoulders.”

Perihan sat back, her body stretched out against the floor. I sat next to her.

“Do you ever bring men here?” she said.

I spat in my chest. “Of course not.”

“Why not?” she insisted.

“Someone would see them. Mother or Father, even Shadia. It’s too risky. And I haven’t met anyone to do that with.”

“If you met someone, would you? You could easily disguise the man as a friend of a family here. You’re the eyes and ears of the neighborhood, so you can sneak in anyone you wanted. There are rich girls all over Egypt who wish they could do the same.”

She was right. “Sometimes,” I divulged, “I see men beautiful enough to invite here. But I don’t, I just come here by myself and imagine them touching me.”

“You come here to masturbate?”

My face flushed and I looked away.

“Don’t, Aisha. Don’t be embarrassed,” she said, and took my face in her hands. I felt strange and still warm. She kissed my cheek. “Don’t be embarrassed,” she said and stroked my face. “Don’t be embarrassed,” she said and kissed my eyelids. “Don’t be embarrassed,” she whispered and pecked my lips. “Don’t be embarrassed,” she said, her tongue sliding into my mouth. I hadn’t kissed anyone in a long time. I knew what we were doing was wrong, but I didn’t know why. I imagined my mother finding us, spitting on me, her mouth grimacing in disgust, and I pulled away. Perihan put her hands on my waist and said again, “Don’t be embarrassed,” and slowly wedged her knee between my legs. I let out a sharp cry and smelled her hair. It was sweet and salty at once. She slid her hands over me, then kissed my neck, my shoulders, my breasts, my stomach, my hips, all the while whispering for me not to be embarrassed. I couldn’t help it. Soon, her hair was caressing the inside of my thighs, and her tongue was on the ridge of my sex. She darted it over me and hummed and groaned, and I looked at the white sheets all around me and sighed. Then she slid a finger inside me and thrust it upwards, as though pressing the timed light-switch. My light clicked on, shone for a while, then went out again. I curled up next to her and closed my eyes.

“Is this what you meant when you told accordion-neck you didn’t like men?” I said. She pulled herself up on one elbow, looked at me, then smiled.

“Yes,” she said. “It is.”

“Have you done this to many women?”

“No. But I was scared at first that there was something wrong with me. I went to many imams and they all said the same thing: what I felt was haram and I should control it. Then I found an imam who told me that nothing in the Koran says a woman can’t love a woman. There’s one verse that says if two women are found together they should be locked up in the house. Then the imam told me that two women locked up in a house could only lead to one thing.” We both laughed. I smelled myself on her breath and hugged her close.

In the following days, I averted my eyes when Mother looked at me. I was ashamed and confused, but then I would hear Peri chanting, “Don’t be embarrassed,” her voice like a phantom-white sheet, and I would feel better. I wondered if she seduced women all over Egypt and then told them the story about the imam to make them feel better. I decided that if she did, it worked. As I pedaled my bike to the market, I looked at men’s bottoms and stared at their hands. Peri had reminded me of so much I’d thought I needed to leave behind, and I was grateful to her for that.

In the afternoons, Perihan and Anna went to Alexandria, to the new library where Peri was doing her research. I searched her eyes for a sign, a way I should behave toward her, but there was nothing, and Perihan simply treated me the way she always had. It was not as though she was pretending nothing had happened between us, only that it would not change the way she saw me or thought of me. It was a bit of a relief, to sense that, though I was still confused about how to feel. One afternoon, she invited me and Shadia to go to the beach. I said I couldn’t go; I was washing the army officer’s car and was not yet done with the windows. She seemed embarrassed for not knowing this—that I was obliged to wash cars. I told her I could go when I was finished.

We spread a few chairs and plowed the sharp wooden end of an umbrella into the sand. A few kids walked up and down the sidewalk holding a crab on a leash. The crab danced and pulled and tugged, facing the shore. While Shadia and Anna swam, Perihan asked me if I ever wanted to leave the building. I said I was like everyone else: I lived where I’d grown up and would probably die there. I told her this gave me comfort on most days, and I faced the blue sea. Perihan said this was an alien idea to her, that she wouldn’t know where home was, even if she wanted to go back. She said that when she came to Egypt, she knew where to go, but that if I ever came to America, she would never know that I was there. “America’s enormous,” she said. The sky was dotted with plastic kites and I watched them float and thought of what she meant. I thought of the kite ripping from the thread and flying away, disappearing into the immeasurable sky. Perihan was like that. I was like the crab on the sidewalk.

The day Peri and Anna left, I made them mulokhiya, picked and dried the mallow leaves myself, and Peri told me I had to eat it with them. We devoured it on the balcony, then the girls went down to play until Perihan’s aunt came to get her. Perihan sat close to me and I saw a couple of eyelashes on her chin. I bent to brush them off but they wouldn’t move. She blushed and said she was hairy-chinned. I told her not to be ashamed, and she rose and began searching for her tweezers. I laughed, then watched the girls drum on tin cans in the street and was saddened that they would not be able to communicate once they got older, once language separated them and play was no longer an option.

“You should teach Anna Arabic,” I said.

“You should teach Shadia English,” she joked, tweezing at a small hand mirror.

“Peri. How will they talk when they get older?” I watched them bang on the drums harder, the suitcases big and bulky on the side of the road. I wondered if Peri would ever come back.

“They’ll find a way,” she said. “Believe me, they’ll still have the language they have now.”

I nodded to be polite, but I didn’t believe it.