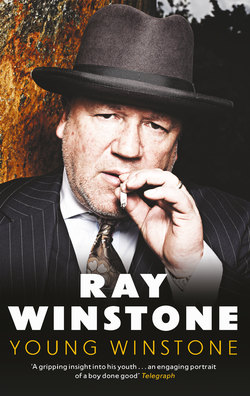

Читать книгу Young Winstone - Ray Winstone - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 4

THE ODEON, EAST HAM

When we first arrived there, in the late fifties, Plaistow was in Essex, which used to reach as far into London as Stratford. But from the day they changed all the boundaries around (1 April 1965, and I think we know who the April Fools were – us), the Essex border got pushed back to Ilford, and Plaistow was bundled up with East and West Ham to become part of the Frankenstein London borough of Newham. Why? What did they want to go and do that for?

Essex is one of the great counties of England. You just have to say the name to know what sense it makes: Wessex was to the west and Essex is to the east, with Middlesex somewhere in the middle. But some soppy cunt who sits in a council office somewhere has a bright idea, and all of a sudden something which has worked very well for hundreds of years has got to change, just so he or she can pat themselves on the back for inventing ‘Newham’.

Ever since I was a little kid, I’ve always been really interested in the mythology of East London – the kind of stories which might or might not be true, but which help to define the character of the place either way. One of my mum and dad’s best friends was a Merchant Navy man who we called Uncle Tony. I learnt a lot from him – he told me all about his voyages round the world as a young man, which probably helped encourage me to want to travel, as that wasn’t something people in my family had tended to do much before. He also had a lot of great stories about the games they used to play in the docks.

For instance, there was one fella whose party piece was to bite the head off a rat. Everyone would bet on whether he could do it or not, then he’d get the rat and put his mouth all around its neck . . . apparently the secret was that you had to do it cleanly, just pull it by the tail and the backbone would come out. Now I’m not recommending anyone try that at home, but being a kid of six or seven and listening to a story like that is certainly going to have an impact on you. As I grew older I loved all the tales about ‘spillage’ – for some reason, the closer you got to Christmas, crates of whisky would get harder to keep a firm hold of – and the canniness of the docklands characters.

There was one about a geezer who owned a pub that used to do lock-ins for the dockers. They’d stay in there all night and then when it got light the next morning they’d go out and go to work. Obviously he didn’t want them to leave, so first he took all the clocks out and then he painted the windows black. They’re all in there having a booze up and since it never gets light, he’s got them in there forever. Looking at that written down, it seems more like a fairy tale than something which actually happened, but I love the dividing line where something would be on the edge of being made up for the sake of the story.

When I was a bit older and started going to Spitalfields Market with my dad, people used to tell me how all the bollards around Gun Street and through the old city of London were made from the old cannon that had helped us win the battles of Trafalgar and Waterloo. Now I don’t know if that was true or not, but either way it gave me a sense of the history of the place. And if we had any reason to be down in the Shadwell or Wapping areas – where the Ratcliff Highway murders took place more than 200 years ago – I’d usually get told how if you’d gone down there at that time it was like some kind of zoo, because sailors would bring back baby giraffes or lions or monkeys as pets, and by the time they’d get them home they’d be fully grown.

Even as a small boy, I was never averse to a bit of make-believe. I had two little girlfriends called Kim and Tracey who lived just up the road from me. They were twins, and we used to play doctors and nurses together (I think I peaked too soon as a ladies’ man). I was always the soldier who came back from the war injured and they had to kiss me better. That was where it all started for me as far as acting was concerned.

Another place that helped incubate the bug was the Odeon, East Ham. There were a couple of local cinemas we used to go to, but this was the main one – it was just near the Boleyn Pub as you go around the West Ham football ground. Do a left onto the Barking road at the end of Green Street and you’re there, down by the pie and mash shop (which we never ate at, because my dad hated pie and mash almost as much as he hated the Salvation Army).

It was a beautiful cinema which had opened just before the Second World War with a live show called Thank Evans starring Max Miller. You’d go in and the organ would come up from the floor and you’d all have a little sing-song. Then you’d get the B-movie before the main picture – you weren’t just in there for a couple of hours, it was the whole afternoon. The first film I ever went to there was 101 Dalmatians, which came out in 1961, so I must have been four.

My mum took me, and by all accounts I got quite angry with Cruella de Vil, because she was bullying the doggies. Apparently I got out of my seat and ran down the aisle towards the screen waving my fists and shouting ‘Cruella de Vil, leave them puppies alone!’ I don’t actually remember doing this myself – the red mist must’ve really come down – but Mum told the story so many times I can’t forget that it happened.

The slant she put on this incident was that I was so trappy as a kid that I ‘even wanted to have a fight with a cartoon’. With hindsight I suppose you could also take it as evidence of how willing I was to get caught up in a drama even then.

Although my mum was the first person who ever took me to the cinema, my dad soon took over the reins. Obviously he had to rise very early to work on the markets. The upside of that was that he tended to be free in the afternoons, and every Wednesday from the age of five onwards he’d pick first me and later me and Laura up from Portway and take us to the pictures. There’s a few stories later on that’ll show Ray Winstone Senior’s harder side, but he was a great dad to us, and I might not be doing what I am now if he’d decided to go down the pub instead of taking his kids to the cinema every week.

Of course, part of his motivation was that he fancied an afternoon kip, but if it was a good film – like 633 Squadron – he’d stay awake to watch it. I remember him falling asleep in Jason and the Argonauts, though, and by the time he’d woken up I’d watched it all the way through twice. We used to see some pretty adult films given how young I was, but the only one I ever remember us being turned away from was a war film called Hell is for Heroes with Steve McQueen and James Coburn in it. I think it was an X, which at the time meant sixteen and over, and I remember the ticket-seller (who knew us) very politely telling my dad, ‘Sorry, Ray, your boy can’t come in.’ With hindsight, I can’t really fault the guy from the Odeon for that. It is quite a violent film – especially the bit where the guy gets shot and you see his glasses crack – and I was only five years old.

Going to the movies wasn’t just a local thing. About once a month, usually on a Sunday afternoon, we’d go up the West End. Cinerama was a big draw then, and we’d go and see big, grown-up films like Lawrence of Arabia or Becket with O’Toole and Burton – which I loved, even though I was only seven when I first saw it.

My nan and granddad took me to see How the West was Won in 70mm, and I had the poster up on my wall with a big map of America and pictures of Annie Oakley on it. Even though grand historical epics were the films I felt most strongly drawn to, I liked stuff that was meant for kids as well. Probably my favourite film of all when I was a youngster was Mary Poppins. Where else do you think I got the accent from?

The Sound of Music was good as well – that was definitely one for the West End.

The only small dampener on going to the cinema with the whole family was Laura saying, ‘I wanna go toilet.’ Sometimes she wouldn’t even last till halfway through, and because Mum would have to take her, we’d all have to stand up so they could make their way out into the aisle.

Even though we went up West regularly, sometimes it felt like people there would dig us out a bit. The first time we saw Zulu was one of those occasions. It’s probably the best film ever, and I know it more or less off by heart now, but the day we went up to Leicester Square to see it has stuck in my mind for a different reason. It’s one of the earliest memories I have of people trying to make us feel like we weren’t good enough to be somewhere.

We’re all sat down, we’ve got our popcorn, sweets and drinks, and the music’s playing. The film hasn’t started – I don’t think the trailers have even started – and obviously there are a few crackling noises as the bags are opening. But this woman sitting behind us with her Old Man almost barks at us, ‘Could you keep the noise down, please?’ My mum twists round with a polite half-shrug and explains, ‘The film hasn’t started yet, darlin’ – we’re just opening the popcorn and some sweets for the kids.’

Obviously a few more sweet-wrappers get rustled over the next couple of minutes, but no one’s making a noise deliberately, and it’s still a while before the film’s due to start. But the woman can’t help herself – she decides to have another go. This time she practically hisses, ‘Keep the noise down’, and the ‘please’ is nowhere to be heard. Now my mum’s had enough. She stands up, turns round to look the woman straight in the eye and says, ‘Do yourself a favour, love, or you’ll be wearing it.’

At that point, the pair of them got up and moved. My dad hadn’t even said anything – because it was a woman causing the trouble and he would never have a go at a woman. He was probably waiting for the bloke to start and then it would really have gone off. I clearly remember the feeling of ‘Oh, sorry, are we not allowed to be here?’ Just because we’re off our manor, suddenly everyone’s going to have something to say about it. This was a feeling I would grow quite familiar with over the years, not just in day-to-day life, but once I started acting as well.

As a small child looking up at that big screen, the idea that I might one day be up there myself would have seemed completely ridiculous. Of course a kid might say they’d ‘like to be in a film’, in the same way they might want to fly a space rocket or captain England at Wembley, but it wasn’t something that was ever going to happen. One of the big differences in those days was you didn’t have the Parkinsons or the Wossies – let alone the internet – so film stars were fantasy figures. That was your two hours of escape, and you believed who they were on the screen was who they were in real life.

That said, we did have one film star in the family already. My cousin Maureen, Charlie-boy’s sister, was an extra in a Charlie Drake film once. It was set in the Barbican, which was where they lived at that time, and when the film came out we all had to go to the pictures to see Maureen in a big crowd of local kids chasing Charlie Drake down the road at the end. Good luck to anyone trying to get a load of local kids together for a crowd scene in the Barbican these days – you’d have to contact their agents first.

The Odeon East Ham’s been through a few changes over the years as well – which one of us hasn’t? The last film they showed with the place as an Odeon was Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty in 1981, but then fourteen years later it reopened as the Boleyn Cinema, which was one of the biggest Bollywood cinemas in Britain. They’d have all the dancing films on, and I’d often go past it on the way to and from West Ham games. But when I went back there specially to have a nose around for this book, I saw it had closed down again. Who knows what’ll happen next? Maybe someone will buy the place up and re-open it screening Polish art films . . . you never know.

Going back to the Plaistow area in 2014, there’s no doubt about what the biggest change is: it’s the shift in the ethnic backgrounds of the people who live there. In the space of a couple of generations, it’s gone from being the almost entirely white neighbourhood my family moved into, to having the predominantly Asian feel that it undeniably does today. Anyone who thinks a population shift of that magnitude in that short a space of time isn’t going to cause a few problems has probably never lived in a place where it’s actually happened.

I remember the first black man who came to live on Caistor Park Road. He was a very smart old Jamaican gent who always wore a zoot suit and a hat with a little turn in it. In truth he probably wasn’t all that old, he just seemed that way. But he was so novel to us that we just used to stare at him and sometimes even (and I realise this isn’t something you’d encourage kids to do today) touch him for luck. He’d just smile and say, ‘Hallo, children’, in a broad Caribbean accent. He knew we didn’t mean any harm by it – we were just kids who hadn’t seen a black man before.

I say that, but in fact we had, in the familiar form of Kenny Lynch, who knew my dad. Lynchy had been on the fringes of my dad’s world for a while – he was a regimental champion boxer in the Army and went on to have a few hit singles (as well as writing ‘Sha La La La Lee’ for Newham local heroes the Small Faces) and sing in the kinds of clubs that the Krays used to run – but I’m not sure if he really booked himself as a black man, or wanted anyone else to for that matter.

When the first West Indian and then Asian people moved in, people weren’t worried about them; they were a novelty. But as more and more came, a feeling began to develop – particularly with regard to the new arrivals from Bangladesh and Pakistan – that they wanted to just stay in their own community rather than joining in with ours. That was what caused the problems: people sticking with their own.

In a way, you couldn’t blame them. They tended to come more from rural areas and maybe had more of an adjustment to make to living in London – if someone from your village goes and lives halfway across the world and they’re your mate, then if you do the same thing, it’s inevitable you’re going to want to join them. And under the pressure of trying to establish yourself in a new environment – especially when what makes you different is visible to all – it’s only natural to close ranks. Looking back now, I can understand the fears they must have had, but there were fears on both sides – fear of losing jobs to people who would work longer hours for less money, fear of the manor you’d lived in all your life being taken away.

Going back to East and West Ham now, they’re not just ‘cosmopolitan’, they’re probably more Bangladeshi and Indian and Pakistani than they are anything else. The positive thing I can see happening in the playground of my old school is that maybe the younger generation are kind of educating us. Whether one side is becoming more Anglicised or the other is becoming less so – or most likely a bit of both – what they’ve got to do is learn to meet in the middle.

Whatever happens, it’s probably not going to be anything that hasn’t happened along the banks of the River Thames plenty of times before. The other side of all those dockyard traditions that have always given the inner London section of the East End its exotic edge is that it’s also always been the place that immigrants have come to first, whether that’s meant the Huguenots or the Chinese or the Jews or the Hindus or the Muslims or the Poles or the Romanians. The docks might be gone now, but the tide still goes in and out.