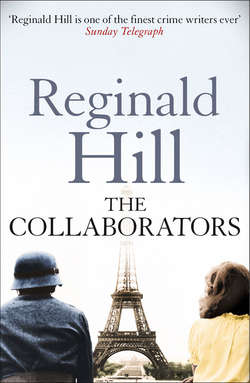

Читать книгу The Collaborators - Reginald Hill - Страница 10

2

ОглавлениеJanine Simonian had dived into the ditch on the other side of the road as the Stukas made their first pass. Like her cousin, she had no arm free to cushion her fall. The left clutched her two-year-old daughter, Cécile, to her breast; the right was bound tight around her five-year-old son, Pauli. They lay quite still, hardly daring to breathe, for more than a minute. Finally the little girl began to cry. The boy tried to pull himself free, eager to view the vanishing planes.

‘Pauli! Lie still! They may come back!’ urged his mother.

‘I doubt it, madame,’ said a middle-aged man a little further down the ditch. ‘Limited armaments, these Boche planes. They’ll blaze away for a few minutes, then it’s back to base to reload. No, we won’t see those boys for a while now.’

Janine regarded this self-proclaimed expert doubtfully. As if provoked by her gaze, he rose and began dusting down his dark business suit.

‘Maman, why do we have to go to Lyon?’ asked Pauli in the clear precise tone which made old ladies smile and proclaim him ‘old-fashioned’.

‘Because we’ll be safe down there,’ said Janine. ‘We’ll stay with your Aunt Mireille and Uncle Lucien. They don’t live in the city. They’ve got a farm way out in the country. We’ll be safe there.’

‘We won’t be safe in Paris?’ asked the boy.

‘Because the Boche are in Paris,’ answered his mother.

‘But Gramma and Granpa stayed, didn’t they? And Bubbah Sophie too.’

‘Yes, but Granpa and Gramma have to look after their shop…’

‘More fool them,’ interrupted the middle-aged expert. ‘I fought in the last lot, you know. I know what your Boche is like. Butchering and looting, that’s what’s going on back there. Butchering and looting.’

With these reassuring words, he returned to his long limousine, which was standing immediately behind Janine’s tiny Renault. He was travelling alone. She guessed he’d sent his family ahead in plenty of time and been caught by his own greed in staying behind to cram the packed limo with everything of value he could lay his hands on.

Janine reprimanded herself for the unkind thought. Wasn’t her own little car packed to, and above, the roof with all her earthly possessions?

Others were following the businessman’s example and beginning to return to the road. There didn’t seem to have been any casualties in this section of the long procession, though from behind and ahead drifted cries of grief and pain.

‘Come on, madame! Hurry up!’ called the man, as if she were holding up the whole convoy.

‘In a minute!’ snapped Janine, who was busy comforting her baby and brushing the dust out of her short blonde fuzz of childish hair.

Pauli rose and took a couple of steps back on to the road where he stood shading his eyes against the sun which was high in the southern sky.

‘They are coming back,’ he said in his quiet, serious voice.

It took a couple of seconds for Janine to realize what he meant.

‘Pauli!’ she screamed, but her voice was already lost in the explosion of a stick of bombs only a couple of hundred metres ahead. And the blast from the next bowled her over back into the protecting ditch.

Then the screaming engines were fading once more.

‘Pauli! Pauli!’ she cried, eyes trying to pierce the brume of smoke and dust which enveloped the road, heart fearful of what she would see when she did.

‘Yes, maman,’ said the boy’s voice from behind her.

She turned. Her son, looking slightly surprised, was sitting in the corn field.

‘It flew me through the air, maman,’ he said in wonderment. ‘Like the man at the circus. Didn’t you see me?’

‘Oh Pauli, are you all right?’

For answer he rose and came to her. He appeared unscathed. The baby was crying again and the boy said gravely, ‘Let me hold her, maman.’

Janine passed the young girl over. Céci often reacted better to the soothing noises made by her brother than to her mother’s ministrations.

Turning once more to the road, Janine rose and took a couple of steps towards the car. And now the smoke cleared a little.

‘Oh Holy Jesus!’ she prayed or swore.

The bomb must have landed on the far side of the road. There was a small crater in the corn field and a couple of poplars were badly scarred and showed their bright green core, almost as obscene as torn flesh and pulsating blood.

Almost.

The businessman lay across the bonnet of his ruined car. His head was twisted round so that it stared backward over his shoulders, a feat of contortion made possible by the removal of a great wedge of flesh from his neck out of which blood fountained like water from a garden hose.

As she watched, the pressure diminished, the fountain faded, and the empty husk slid slowly to the ground.

‘Is he dead, maman?’ enquired Pauli.

‘Quickly, bring Céci. Get into the car!’ she shouted.

‘I think it’s broken,’ said the boy.

He was right. A fragment of metal had been driven straight through the engine. There was a strong smell of petrol. It was amazing the whole thing hadn’t gone up in flames.

‘Pauli, take the baby into the field!’

Opening the car door she began pulling cases and boxes on to the road. She doubted if the long procession of refugees would ever get moving again. If it did, it was clear her car was going to take no part in it.

She carried two suitcases into the corn field. As she returned a third time, there was a soft breathy noise like a baby’s wind and next moment the car was wrapped in flames.

Pauli said, ‘Are we going back home, maman?’

‘I don’t know,’ she said wearily. ‘Yes. I think so.’

‘Will papa be there?’

‘I don’t think so, Pauli. Not yet.’

If there’d been the faintest gleam of hope that Jean-Paul would return before the Germans, she could never have left. But the children’s safety had seemed imperative.

She looked at the burning car, the bomb craters, the dead businessman. So this was safety!

‘Maman, will the Germans have stopped butchering and looting now?’ asked the boy.

‘Pauli, save your breath for walking.’

And in common with many others who had found there is a despair beyond terror, she set off with her family back the way they had come.