Читать книгу The Collaborators - Reginald Hill - Страница 13

1

ОглавлениеThere was no getting away from it, thought Günter Mai. Even for an Abwehr lieutenant who was more likely to see back alleys than front lines, it was nice to be a conqueror. Not nice in a brass-banded, jack-booted, Sieg Heiling sort of way. But nice to be here in this lovely city, in this elegant bedroom in this luxurious hotel which for the next five? ten? twenty? years would be the Headquarters of Military Intelligence in Paris.

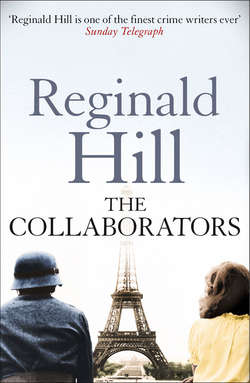

He gazed out across the sun-gilt rooftops to the distant mast of the Eiffel Tower and saluted the view with his pipe.

‘Thank you, Paris,’ he said.

Behind him someone coughed, discreet as a waiter, but when he turned he saw it was his section head, Major Bruno Zeller.

‘Good morning, Günter,’ said the elegant young man. ‘I missed you at breakfast. Can my keeper be ill, I asked myself.’

‘Morning, sir. I wasn’t too hungry after last night’s celebration.’

‘You mean you ate as well as drank?’ said Zeller lounging gracefully on to the bed. ‘You amaze me. Now tell me, do you recall a man called Pajou?’

Mai’s normally round, amiable face lengthened into a scowl. A hangover reduced his Zeller-tolerance dramatically. In his late twenties, he had long got over the irritation of having to ‘sir’ someone several years his junior. Such things happened, particularly if you were the son of an assistant customs officer in Offenburg and ‘sir’ was heir to some turreted castle overhanging the Rhine, not to mention a distant relative of Admiral Canaris, head of the Abwehr.

But that didn’t entitle the cheeky child to wander at will into your bedroom and lie across your bed!

‘Pajou. Now let me see,’ said Mai. Yes, of course, he remembered him well. But having remembered, it now suited him to play the game at his speed. From his dressing-table he took a thick black book. It was an old Hitler Jugend Tagebuch which he’d never found any use for till he started in intelligence work. Now, filled with minuscule, illegible writing, it was the repository of all he knew. He guessed Zeller would pay highly for a fair transcript. He saw the young man’s long, manicured fingers beat an impatient tattoo on the counterpane. The movement caught the light on his heavy silver signet ring, reminding Mai of another source of irritation. The signet was the family heraldic device, basically a Zed crossed by a hunting horn. On first noticing it, Mai had remarked unthinkingly that he had seen a similar device on some brass buttons which he thought came from a coat belonging to his grandfather. Zeller had returned from his next visit to his widowed mother delighted with the news, casually introduced, that there had been an under-keeper called Mai working on the family’s Black Forest estate till he’d gone off to Offenburg to better himself. ‘And here’s his grandson, still working for the family in a manner of speaking! Strange how these things work out, eh, Günter?’

Thereafter he often referred to Mai as ‘my keeper’, though it had to be said he didn’t share the joke with other people.

Mai took it all in good part - except when he had a hangover. Basically he quite liked the young major. Also there were other shared pieces of knowledge which dipped the scales of power in his favour.

One, unusable except in the direst emergency, was that Zeller was as queer as a kosher Nazi and was no doubt already looking for some Gallic soulmate to criminally waste his precious Aryan seed on.

Another, and more important for everyday working, was that Mai was twice as good at the job as his boss, though Zeller compensated by taking twice the credit.

He began to read from the book.

‘Pajou, Alphonse. Worked for the National Armaments Company. I recruited him in Metz in ‘38. No political commitment, in it purely for the money. Got greedy, took risks and got caught. Tried and gaoled just before the war. Lucky for him. Any later and he’d have got the guillotine. So, what about him?’

‘It seems he got an early release, unofficially I guess, and would like to make it official by re-entering our employ. He’s not very trusting, however. The duty sergeant says he insisted on dealing with you when he rang earlier this morning.’

‘Why didn’t he put the call through then?’ asked Mai.

‘The sergeant says that you left instructions last night that you weren’t to be disturbed by anything less than a call from the Führer and not even then if he wanted to transfer the charge.’

Mai grimaced behind a puff of smoke.

‘Sorry about that, sir. Look, I’m not sure Pajou’s the kind of man we want just now. Basically he’s a nasty piece of work and he’s not even a native Parisian. What we ought to be doing now, before the first shock fades and people begin to take notice, is establishing a network of nice ordinary citizens who’ll feed us with intelligence just for the sake of reassurance that the dreadful Hun is a nice ordinary chap like themselves.’

‘Clever thinking, Günter. But in the end we’ll doubtless need the nasties, so we might as well recruit Pajou now. If we don’t no doubt the SD will when they arrive.’

The Sicherheitsdienst was the chief Nazi intelligence gathering service. With France under military control, the SD ought not yet to have a presence, let alone a function.

’When!’ said Mai. ‘I heard the bastards were already settling in at the Hôtel du Louvre. And I’m sure I saw Fiebelkorn in the restaurant last night - in civvies, of course, not his fancy SS colonel’s uniform.’

‘Let’s hope it was a drunken delusion,’ said Zeller with a fastidious shudder.

‘One thing, if they’ve started showing their faces, it means the fighting’s definitely over. Right, sir, I’ll talk to Pajou if he rings back.’

‘No, you’ll talk to him face to face,’ said Zeller, rising gracefully. ‘He left word that he would look for you by the Medici Fountain at ten-thirty this morning. That gives you just half an hour.’

‘But breakfast…’ objected Mai, genuinely indignant.

‘I thought you weren’t hungry. Anyway a good keeper should have been doing the rounds of his estate at the crack of dawn. Let me know how you get on, won’t you?’

With a smile and a sort of waving salute, Zeller left.

‘Go stuff yourself,’ murmured Mai, but he began to get ready. Zeller expected obedience in small matters, and though Mai had been looking forward to his favourite hangover cure of sweet black coffee and half a dozen croissants, it wasn’t worth the risk of irritating him into some petty revenge.

He clattered through the lobby of the hotel trying to look brisk and businesslike, but once out into the gentle morning sunlight, he slowed to strolling pace. Sod Pajou. He could wait. What was more, he would wait. He wasn’t selling information today, he was applying for a job!

It was good to see how things were coming back to normal. The Bon Marché emporium which he could see at the far side of the garden opposite the hotel had reopened and looked to be doing good business. He must go on a shopping expedition himself soon. Victory or no victory, there’d soon be shortages he guessed. And a nice supply of silks and perfume would be useful on his next home leave.

He strolled on, taking deep breaths of the rich enchanted air. His mind, ever ready to deflate, reminded him that at this hour of the morning the air would normally have been rich indeed - with the stench of exhaust fumes.

You see how we’re improving things already! he mentally addressed the city.

Gradually he became aware that the air was indeed richly scented. Wandering by half-memory, he had turned into the Rue d’Assas. It ought to lead him roughly towards the Luxembourg. In any case, he liked the sound of the name. Eventually he reached a narrow crossroads where the Rue Duguay-Trouin entered and the Rue de Fleurus intersected the Rue d’Assas. Looking left, he could see down to the Gardens. But his nose was turning him away to the right. He followed it along the narrow street till his eyes could do their share of the work and identify the source of that rich, warm smell.

It was a baker’s shop, not very big, but dignified by the words Boulangerie Pâtisserie parading above the windows in ornate lettering, and decorated by glass-covered designs around the door which featured a sturdy farmer and his elegant wife and promised ‘Pains Français et Viennois, Pains de Seigle, Chaussons aux Pommes et Gâteaux Secs’.

On the glass of the door was engraved ‘Crozier Père et Fils depuis 1870’, underlined by a triangle of curlicues, eloquent of the pride with which that first Crozier had launched his business seventy years before. The same year in which, if Mai’s history served him well, the Franco-Prussian war began. Perhaps other occupying Germans had been customers at this shop!

The shop window was fairly bare. But the smell of baking was rich and strong.

He pushed open the door and went in. There was one customer, one of those Frenchwomen of anything between fifty and a hundred who wear black clothes of almost Muslim inclusiveness whatever the weather. She was being served by a stout woman in middle age with the kind of flesh that looked, not unfittingly, as if it had been moulded from well-kneaded dough.

The black-swathed customer looked in alarm at Mai’s uniform, said abruptly, ‘Good morning, Madame Crozier,’ and left.

‘Good morning, Madame Duval,’ the stout woman called after her. ‘Monsieur?’

Her attempt at sang-froid failed miserably.

He set about allaying her fears.

‘Madame,’ he said in his rolling Alsatian French. ‘I have been drawn here by the delectable odours of what I’m sure is your superb baking. I would deem it an honour if you would allow me to purchase a few of your croissants.’

The woman’s doughy features stretched into a simper.

‘Claude!’ she shouted.

The door behind her opened, admitting a great blast of mouth-watering warmth and a man cast in the same mould, and from the same material, as his wife.

‘What?’ he demanded. Then he saw the uniform, and his face, which would have made him a fortune in the silent movies, registered fearful amazement.

‘Good day, monsieur,’ said Mai. ‘I was just telling your wife how irresistible I found the smell of your baking.’

‘Claude, are there any more croissants? The officer wants croissants,’ said Madame Crozier peremptorily.

‘No, I’m sorry…’ began the man.

‘Well, make some, Claude,’ commanded the wife. ‘If the officer would care to wait, it will only take a moment.’

The man went back into the kitchen and the woman brought Mai a chair. As she returned to the counter the door burst open. A good-looking woman of about twenty-five with dishevelled fair hair and a pale smudged face rushed in. She was carrying a child of about two years and at her heels was a boy a few years older.

She cried, ‘Maman, are you all right? Madame Duval said the Boche were here!’

‘Janine!’ exclaimed the woman. ‘What are you doing back? Why aren’t you in Lyon? Oh the poor baby! Is she ill?’

The child in arms had begun to cry. Madame Crozier reached over the counter and took her in her arms with much cooing.

‘No, she’s just hungry,’ said the girl, then broke off abruptly as for the first time she noticed Mai sitting quietly in the corner, almost hidden by the door. She was not however the first of the newcomers to notice him. The young boy’s eyes had lit on him as soon as he came in and the lad had thereafter fixed him with a disconcertingly level and unblinking gaze.

Mai got to his feet.

‘I’m sorry, madame,’ he said. ‘Please do not let me disturb this reunion.’

‘No, wait,’ cried Madame Crozier. ‘Claude! Where are those croissants?’

‘They’re coming, they’re coming!’ came the reply, followed almost immediately by the opening of the door. Once again Mai had the pleasure of seeing that cinematic amazement.

‘Janine!’ cried Crozier. ‘What’re you doing here? Why’ve you come back?’

‘Because the Boche dropped bombs and fired bullets at everyone on the road,’ cried Janine vehemently. ‘They could see we were a real menace. Men, women, children, animals, all running south in terror. Oh yes, we were a real menace!’

Sighing, Mai put on his cap. Not even the best croissants in the world were worth this bother.

‘But you’re not hurt, are you? And the children are all right? Claude, the officer’s croissants!’

The man put the croissants in a bag and handed it to Mai. He reached into his pocket. The woman said, ‘No, no. Please, you can pay next time.’

A good saleswoman thought Mai approvingly. Ready to risk a little for good will and the prospect of a returning customer. The young woman was regarding him with unconcealed hostility. As he took the croissants he clicked his heels and made a little bow just as Major Zeller would have done. She too might as well have her money’s worth.

He left the shop, pausing in the doorway as if deciding which way to go. Behind him he heard the older woman say, ‘Oh look at the poor children, they’re like little gypsies. And you’re not much better, Janine.’

‘Mother, we’ve been walking for days! We slept in a barn for two nights. Has there been any news of Jean-Paul?’

‘No, nothing. Now come and sit down and have something to eat. Pauli, child, you look as if you need fattening for a week. Claude, coffee!’

Mai left, smiling but thoughtful. These French! Some of his masters believed that, properly handled, they could be brought into active partnership with their conquerors. With the baker and his wife it might be possible. Be correct, avoid provocative victory parades, use clever propaganda, offer them a fair armistice and business as usual; yes they might grumble, but only as they grumbled at their own authorities. But they’d co-operate.

Alas, not all the French were like Monsieur and Madame Crozier. Take that girl, so young, so child-like, but at the same time so fierce!

He turned left at the Bassin in the Luxembourg Gardens. As he skirted the lush green lawn before the Palace, he saw two German soldiers on guard duty. They were looking towards him and he remembered he was still in uniform. The sooner he got out of it the better. One of the joys of being an Abwehr officer was the excuse it gave for frequently wearing civilian clothes. The sentries offered a salute. He returned it, realized he was still clutching a croissant, grinned ruefully and bore right to the Medici Fountain.

Slowly he made his way alongside the urn-flanked length of water to take a closer look at the sculpture. In the centre of three niches a fierce-looking bronze fellow loomed threateningly above a couple of naked youngsters in white marble. Us and the French! he told himself, crumbling a croissant for the goldfish.

A hand squeezed his elbow. He started, turned and saw a thin bespectacled man showing discoloured teeth in a smile at once impudent and ingratiating.

‘Hello, lieutenant. Didn’t use to be able to creep up on you like that!’

‘Hello, Pajou,’ said Mai coldly.

The man turned up the ingratiating key.

‘I was really glad when I realized you were in town, lieutenant. That Mai’s a man I can trust, a man I can talk to. So here I am, reporting for duty. Do you think you can use me?’

Mai returned his gaze to the crouching cyclops, Polyphemus, poised so menacingly over the entwined figures of Acis and Galatea.

‘Yes, Pajou,’ he sighed. ‘I very much fear we can.’