Читать книгу Death’s Jest-Book - Reginald Hill - Страница 22

St Godric’s College

ОглавлениеCambridge

| Sat Dec 15th | The Quaestor’s Lodging |

My dear Mr Pascoe,

Honestly, I really didn’t mean to bother you again, but things have been happening that I need to share and, I don’t know why, you seemed the obvious person.

Let me tell you about it.

I got down to the Welcome Reception in the Senior Common Room, which I found to be already packed with conference delegates, sipping sherry. Supplies of free booze are, I gather, finite at these events and the old hands make sure they’re first at the fountain.

The delegates fall roughly into two groups. One consists of more senior figures, scholars like Dwight who have already established their reputations and are in attendance mainly to protect their turf while attempting to knock others off their hobby-horses.

The second group comprises youngsters on the make, each desperate to clock up the credits you get for attendance at such do’s, some with papers to present, others hoping to make their mark by engaging in post-paper polemic.

I suppose that to the casual eye I fitted into this latter group, with one large difference – they all had their feet on the academic ladder, even if the rung was a low one.

Of course I didn’t take all this in at a glance as you might have done. No, but I related what I saw and heard to what Sam Johnson had told me in the past and also to the more recent and even more satirical picture painted by dear old Charley Penn when he learned I was about to attend what he called my first ‘junket’.

‘Remember this,’ he said. ‘However domesticated your academic may look, he is by instinct and training anthropophagous. Whatever else is on the menu, you certainly are!’

Anthropophagous. Charley loves such words. We still play Paronomania, you know, despite the painful memories it must bring him.

But where was I?

Oh yes, with such forewarning – and with the experience behind me of having been thrown with even less preparation into Chapel Syke – I felt quite able to survive in these new waters. But in fact I didn’t even have to work at it. Unlike at the Syke where I had to seek King Rat out and make myself useful to him, here at God’s he came looking for me.

As I stood uncertainly just within the doorway, the only person I could see in that crowded room that I knew was Dwight Duerden. He was talking to a long skinny Plantagenet-featured man with a mane of blond hair so bouncy he could have made a fortune doing shampoo ads. Duerden spotted me, said something to the man, who immediately broke off his conversation, turned, smiled like a time-share salesman spotting an almost hooked client, and swept towards me with the American in close pursuit.

‘Mr Roote!’ he said. ‘Be welcome, be welcome. So delighted you could join us. We are honoured, honoured.’

Now the temptation is to class anyone who talks like this, especially if his accent makes the Queen sound Cockney and his manner is by Irving out of Kemble and he’s wearing a waistcoat by Rennie Mackintosh with matching bow tie, as a prancing plonker. But Charley’s warning still sounded in my mind so I didn’t fall about laughing, which was just as well as Duerden said, ‘Franny, meet our conference host, Sir Justinian Albacore.’

I said, ‘Glad to meet you. Sir Justinian.’

The plonker flapped a languid hand and said, ‘No titles, please. I’m J. C. Albacore to my readers, Justinian to my acquaintance, plain Justin to my friends. I hope you will feel able to call me Justin. May I call you Franny?’

‘Wish I had a title I could ignore,’ said Duerden sardonically.

‘Really, Dwight? That must be the one thing Cambridge and America have in common, a love of the antique. When I worked in the sticks, they’d have thrown stones at me if I’d tried to use my title. But here at God’s, antiquity both in fact and in tradition is prized above rubies. Our dearest possession is one of the earliest copies of the Vita de Sancti Godrici, you really must see it while you’re here, Franny. Gentlemen –’ this to a group of distinguished looking old farts – ‘let me introduce Mr Roote, a new star in our firmament and one which we have hopes will burn very brightly.’

Like Joan of Arc, I thought. Or Guy Fawkes.

During all this prattle, I was trying to work out Albacore’s game. Did he really think I was such an innocent abroad that simply by giving me a nice room and bulling me up in front of the nobs he could sweet talk Sam’s unique research notes out of me in time to incorporate them in his own book?

Perhaps looking down on the world from the mountain deanery of a Cambridge college gives a man a hearty contempt for the little figures scuttling around below. If so, I assured myself grandiloquently, he would soon find that he’d underestimated me.

Instead, I quickly came to realize that I’d underestimated him.

After the reception we all adjourned to a lecture room where the official business of the conference began with a formal opening followed by a keynote address from Professor Duerden on the theme ‘Imagining What We Know: Romanticism and Science’.

It was interesting enough, he had a dry Yankee wit (he comes from Connecticut; fate and a tendency to bronchitis took him to California) and was a master in the art of being provocative without going out on a limb. I listened with interest from my reserved seat on the front row, but part of my mind remained concentrated on the puzzle of Albacore, whose duties as chair of the meeting kept him from his other task of stroking my ego.

But when the lecture and subsequent discussions were over and we were all dispersing to our rooms, my new friend Justin was at my side again, his hand on my elbow as he guided me out into the quad and away from the general drift of delegates.

‘And what did you think of our transatlantic friend?’ he said.

‘It was a real honour to hear him,’ I gushed. ‘I thought he put things so well, though I’ve got to admit, a lot of it was well over my head.’

I’d decided to have a bit of fun with this idiot by playing the eager and enthusiastic but not too bright student and seeing where that led. I didn’t expect my performance to provoke cynical laughter.

‘Oh, I don’t think so, young Franny,’ he said, still chuckling. ‘I think an idea would have to be very deep indeed to be over your head.’

This didn’t sound like simple flannel any more.

‘Sorry?’ I said. ‘Don’t quite follow.’

‘No? I’m simply letting you know what a great respect I’ve got for your mental capacities, dear boy.’

I said, ‘That’s very flattering, but you hardly know me.’

‘On the contrary. You and I are long acquainted and I know all your ways.’

He looked down at me from his height, eyes twinkling like distant stars.

And suddenly I was there.

J.C. to his readers. Justinian to his acquaintance. Justin to his friends.

And to his wife, Jay.

I said, ‘You’re Amaryllis Haseen’s husband.’

It seems so obvious now. Probably you with your fine detective mind got there long before me. But you can see how the revelation bowled me over, especially as I’d spent so much time earlier today raking up that bit of my past for your benefit. Nothing is for nothing in this life, so Frère Jacques preaches. The past isn’t another country. It’s just a different part of the maze we travel through, and we shouldn’t be surprised to find ourselves re-entering the same stretch from a different angle.

Albacore was spelling things out.

‘My wife developed a very high opinion of your potential, Franny. She says that in terms of simple academic cleverness you are bright enough to hold your own in most company. But she also detected in you another kind of cleverness. How did she put it? A mind fit for stratagems, an eye for the main chance, nimble of thought, sharp in judgment, ruthless in execution. Oh yes, you made a big impression on her.’

I said, ‘And on you too, from the sound of it.’

‘Hardly,’ he said, smiling. ‘I was amused when she told me how you neatly got her in a neck lock. But at the time I was on my way from the ghastly wasteland of South Yorkshire back to God’s own college, and apart from a little chortle at the idea of dear Sam Johnson being landed with a cunning convict as a PhD student, I never gave you another thought. Not of course till I heard about poor Sam’s sad demise. Couldn’t make the obsequies myself, but a friend described the dramatic part you played in them, and I thought, hello, could that be that chappie whatsisname? Then I heard that Loopy Linda had appointed you as Sam’s literary heir or executor or some such thing, which was when I asked Amaryllis to dig out all her old case notes.’

‘I’m surprised you didn’t just read her book,’ I said.

He shuddered and said, ‘Can’t stand the way she writes, dear boy. Subject matter is generally tedious and her style is what I call psycho-barbarous. In any case, it’s the marginalia of her case notes that make the most interesting reading. Unless she is wrong, which she rarely is, you are someone I can do business with.’

‘The business being the redistribution of Sam Johnson’s Beddoes research,’ I said.

‘There. I knew I was right. No need to soft soap a supple mind.’

‘No? Then why do I feel so well oiled?’ I wondered. ‘The Q’s Lodging, all these flattering introductions.’

‘Samples,’ he said. ‘Simply samples. When you’re getting down to a trade-off, you have to give the man you’re trading with a taste of your wares. You see, I’m very aware that while I know what you have to offer, you may have doubts about what’s in my poke. It’s little enough unless it’s what you want, and then it’s the world. It is this –’

He made a ring master’s gesture which comprehended the quad, and all the buildings around it, and much much more.

‘If it is something you’re not interested in, then we must look for other incentives,’ he went on. ‘But if, as from my brief observation of you in person I begin to hope, this cloistered life of ours, in which the intellect and the senses are so deliciously catered for, and the inhibiting morals kept firmly in their place, has some strong attraction, then we can get down to business straight off. I have influence, I have contacts, I know where many bodies are buried, I can put you on a fast-track academic career, get you on the cultural chat shows, if that is your desire, I can put you in the way of editors and publishers. In short, I can be thy protector and thy guide, in thy most need to go by thy side. So, do I judge right? Can we do business?’

This was straight talking with a vengeance. This was complete no-holds-barred honesty, which is always a cause for grave suspicion.

Time to test him out with some of the same.

‘If I want these things you offer,’ I said, ‘what is to stop me getting them for myself? I am, as you acknowledge, bright. I may be, as your wife alleges, ruthlessly manipulative. Your book, I presume, is mainly a reworking of the few known facts of Beddoes’ Continental life, embellished, no doubt, by whatever you were able to lift from Sam before he became aware of your perfidy.’

That hit home, just a flicker of reaction, but I got used to reading flickers in the Syke when not to read them could mean losing a game of chess. Or an eye.

I pressed on.

‘Sam, however, as your interest confirms you know, had tracked down a substantial body of new material in various forms. Wherever your book stood in relation to his, coming before or after, it was always going to stand in the shade.’

I paused again.

He said, ‘And your point is … ?’

I said, ‘And my point is, why should I bargain for what is already within my grasp?’

He smiled and said, ‘You mean, complete Sam’s book yourself, bathe in what would be mainly a reflected glory, then make your own way onward and upward? Perhaps you could do it. But it’s a hard road, and other men’s flowers quickly wilt. I naturally cannot be expected to agree with what you say about my book being in the shade, though what I am certain of is that it will be in the way. But if you can find someone willing to take a punt on a total unknown, then perhaps you should go ahead, dear Franny.’

He knew, the bastard knew, that Sam’s pusillanimous publishers had developed feet so cold they were walking on chilblains.

He saw my reaction and pressed his advantage.

‘How’s your thesis going, by the way? Have you found a new supervisor? Now there’s a thought. Perhaps I could offer my own services? It would mean moving to Cambridge, but if you’re heading high, no harm starting on the upper slopes, is there?’

Perhaps I should have said, get thee behind me, Satan! But any belief I might have had in my own divine indestructibility vanished back at Holm Coultram College when, despite my very best efforts, you managed to finger my collar.

So, please don’t despise me, I said I’d think about it.

I thought about it all evening, paying little attention to the conference sessions I attended and barely picking at the buffet supper that was laid on for us. (There’s a big formal dinner in the college hall tomorrow night, but meanwhile, sherry apart, it’s the appetites of the intellect that are being catered for.)

And I’m still thinking about it now even as I write. Please forgive me if I seem to be going on at unconscionable length, but in all the world there is no one I can talk to so fully and frankly as I can to you.

Time for bed. Will I sleep? I thought I had learned in prison how to sleep anywhere in any conditions, but tonight I think I may find it hard to close my eyes. Thoughts wriggle round my head like little snakes nesting in a skull. What do I owe to dear Sam? What do I owe to myself? And whose patronage was the more precious, Linda Lupin’s or Justin Albacore’s? Which would a wise man put his trust in?

Goodnight, dear Mr Pascoe. At least I hope it will be for you. For me I see long white hours lying awake pondering these matters, and above all the problem of how I’m going to reply to Albacore’s offer.

I was wrong!

I slept like a log and woke to a glorious morning, bright winter sunshine, no wind, a nip in the air but only such as turned each breath I took into a glass of champagne. I was up early, had a hearty breakfast, and then went out for a walk to clear my head and still my nerves before I read Sam’s paper at the nine o’clock session. I left the college by its rear gate and strolled along beside the Cam, admiring what they call the Backs. The Backs! Only utter certainty of beauty allows one to be so throwaway about it. Oh, it’s a glorious spot this Cambridge, Mr Pascoe. I’m sure you know it well, though I can’t recall whether you’re light or dark blue. This is a place for youth to expand its soul in, and despite everything, I still feel young.

I didn’t see Albacore until I arrived in the lecture theatre a few minutes before nine and saw his cunicular nose twitch with relief. He must have been worrying that his ‘straight talk’ last evening had been too much for my weak stomach and I’d done a runner!

He’d arranged for me to have a plenary session and every chair was taken. He didn’t hang about – perhaps recognizing more than I did at that moment just how nervous I was – but introduced me briefly with, mercifully, only a short formal reference to Sam’s tragic death, while I sat there staring down at the opening page of my lost friend’s paper.

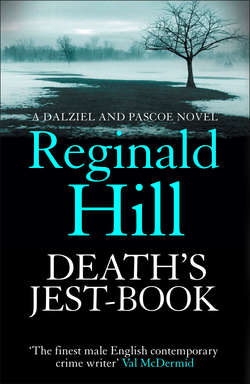

Its title was, ‘Looking for the Laughs in Death’s Jest-Book’.

I read the first sentence – In his letters Beddoes refers to his play Death’s Jest-Book as a satire: but on what? – and tried to turn the printed words into sounds coming from my mouth, and couldn’t.

There was a loud cough. It came from Albacore, who had taken his place in the front row. And next to him, looking up at me with those big violet eyes I recalled from our sessions in the Syke, was his wife, Amaryllis Haseen.

Perhaps the sight of her was the last straw that broke what remained of my nerve.

Rising from my chair was the hardest thing I’d ever done in my life. I must have looked like a drunk as I walked the few steps to the lectern. Fortunately it was a solid old-fashioned piece of furniture, otherwise it would have shaken with me as I hung on to it with both hands to control my trembling. As for my audience, it was as if they were all sitting at the bottom of a swimming pool and I was trying to see them through a surface broken by ripples and sparkling with sun-starts. The effort made me quite nauseous and I raised my eyes to the back of the lecture theatre and stared at the big clock hanging on the wall there. Slowly its hands swam into focus. Nine o’clock precisely. The distant sound of bells drifted into the room. I lowered my eyes. The swimming-pool effect was still evident, except in the case of one figure sitting in the middle of the back row. Him I could see pretty clearly with no more distortion than might have come if I’d been looking through glass. And yet I knew that this must be completely delusional.

For it was you, Mr Pascoe. There you were, looking straight at me. For a few seconds our gazes locked. Then you smiled encouragingly and nodded. And in that moment everyone else came into perfect focus, I stopped trembling, and you vanished.

Wasn’t that weird? This letter I’m writing must have created such a strong subconscious image of you that my mind, desperately seeking stability, externalized it in my time of need.

Whatever the truth of it, all nerves vanished and I was able to put on a decent show.

I even managed to say a few words about Sam, nothing too heavy. Then I read his paper on Death’s Jest-Book. Do you know the play? Beddoes conceived it at Oxford when he was still only twenty-one. ‘I am thinking of a very Gothic-styled tragedy for which I have a jewel of a name – DEATH’S JESTBOOK – of course no one will ever read it.’ He was almost right, but as he worked on it for the rest of his short life, it has to be pretty central to any attempt to analyse his genius.

Briefly, it’s about two brothers, Isbrand and Wolfram, whose birthright has been stolen, sister wronged, and father slain by Duke Melveric of Munsterberg. Passionate for revenge, they take up residence at the ducal court, Isbrand in the role of Fool, Wolfram as a knight. But Wolfram finds himself so attracted to the Duke that, much to Isbrand’s horror and disgust, they become best buddies.

Sam’s theory is that the whole eccentric course of Beddoes’ odd life was dictated by his sense of being left adrift when his own dearly beloved father died at a tragically early age. One aspect of the poet’s search for ways to fill the gap left by this very powerful personality is symbolized, according to Sam, by Wolfram finding solace not in killing his father’s killer but rather in turning him into a substitute father. Unfortunately, for the integrity of the play that is, this search had many other often conflicting aspects, all of which dominate from time to time, leading to considerable confusion of plot and tone. As for Death, he is by turns a jester and a jest, a bitter enemy and a seductive friend. Keats, you will recall, claimed sometimes to be half in love with easeful death. No such pussy-footing about for our Tom. His was a totally committed all-consuming passion!

Back to my conference debut. I finished the paper without too much stuttering, managed to add a few comments of my own, and finally took questions. Albacore was in there first, his question perfectly weighted to give me every chance to shine. Thereafter he managed the session like an expert ringmaster, guiding, encouraging, gentling, and always keeping me at the centre of things. Afterwards I was congratulated by everyone whose congratulation I would have prayed for. But not Albacore. He didn’t come near me, though I caught his eye occasionally through the crowd and received a friendly smile.

I knew what he was doing, he was showing me what he could do.

And I discovered by listening and asking questions some interesting things about the set-up here. At God’s the Master is top dog, the present one being a somewhat remote and ineffectual figure, leaving the real power in the hands of his 2i/c, the Dean. (The Quaestor, incidentally, is what they call their bursar.) Albacore in fact is presently deputizing for the Master, who’s on a three-month sabbatical at the University of Sydney. (Sydney, for godsake! During an English winter! These guys know how to arrange things!) On his return he will be entering the last year of his office. Albacore naturally enough is in the van of contenders for his job, but, this being Cambridge, the succession is by no means cut and dried. A big successful book, appearing just as the hustings reached their height, would be a very useful reminder to the electorate (which is to say, God’s dons – sounds like the Vatican branch of the Mafia, doesn’t it?) that Albacore could still cut the mustard academically, and its hoped-for popular success would give him a chance to demonstrate that he had Open Sesames to the inner chambers of that media world where so many of your modern dons long to strut their stuff.

Oh, the more I got the rich sweet smell of it, the more I thought, this is the life for me! Reading and writing, wheeling and dealing, life in the cloisters and life in the fast lane running in parallel, with winters in the sun for those who made the grade.

But I wasn’t going to rush into a decision as important as this. I slipped away back here to the Lodging to think it all through and there seemed no better way of doing this than pouring out all my thoughts and hopes to you. Like that vision I had of you this morning, it’s almost like having you here in the room with me. I can sense your approval at the now final decision I have reached.

This quiet, cloistered but not inactive nor unexciting life in these most ancient and fructuous groves of academe is what I want. And if giving up Sam’s research is the only way for me to get it, I’m sure that’s what he’d have wanted me to do.

So the die is cast. I’ll stroll out now and post this letter, then perhaps catch one of the afternoon sessions. If I bump into Albacore, I won’t give him any hint of the way I’m thinking. Let him sweat till tonight at least!

Thanks for your help.

Yours in gratitude,

Franny Roote