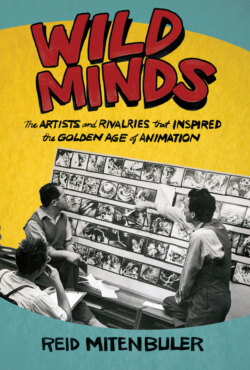

Читать книгу Wild Minds - Reid Mitenbuler - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 5

“Cherubs That Actually Fly”

Two years after the release in 1914, of Gertie the Dinosaur, Winsor McCay found himself going through a professional rough patch. The relationship with his boss, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, was strained. Hearst thought McCay was spending too much time on animation and not enough on his comic strips. Winsor hadn’t come cheap, and Hearst didn’t think his work was as good as it used to be.

As one of the most ruthless moguls in a ruthless field, Hearst was not a man to tangle with. He had started in the newspaper business in 1887, at the age of twenty-three, when his millionaire father gave him control of the San Francisco Examiner after winning the paper in a high-stakes poker game. Hearst’s entry into the business was random—a rich kid inheriting a plaything—but he quickly developed a taste for it, shrewdly buying up competitors until he was the most powerful media baron in the nation. At the peak of his career, nearly a fifth of the U.S. population would subscribe to his newspapers. Politically ambitious, he twice won a seat in Congress and unsuccessfully ran for president in 1904, using his media empire to cudgel his political enemies. Not surprisingly, he demanded devout loyalty from anyone working for him.

Much of McCay’s time away from the office was spent on the road, where he showed Gertie in vaudeville theaters. It was a tough circuit; most performers spent years bouncing from one dingy theater to another, clawing their way up its ranks. But Winsor had shot straight to the top, from the start playing some of the most prestigious houses in New York: Proctor’s Fifth Avenue, the Alhambra, B. F. Keith’s Palace, and the Victoria, perhaps the most prestigious theater in the nation. “No one, however good an act, [is] important enough to play the Victoria unless he [has] a tremendous reputation,” theater owner Willie Hammerstein boasted. McCay shared bills with W. C. Fields, Will Rogers, and Harry Houdini—the top names in show business. “His act is one of the most interesting and novel seen in vaudeville in some time,” the New York Telegraph said.

The situation between McCay and Hearst boiled to a head one night while McCay was away performing his animated Gertie routine. Hearst was back at the office and had an editorial question about a cartoon that McCay had drawn for his star columnist, Arthur Brisbane. When Hearst asked where McCay was, the staff told him he was performing his vaudeville show at the Victoria. Handling the matter personally, Hearst phoned the theater and his call was answered by a stagehand.

Winsor “can’t come now. He’s busy,” the stagehand said abruptly before hanging up, unaware of who the caller was.

Hearst’s reaction was swift. The next morning, one of his papers, the Morning Telegraph, announced: “Hearst to Stop Vaudeville Engagements of Cartoonists.” Theater mogul Willie Hammerstein also discovered that advertisements for his vaudeville acts were banned from appearing in Hearst’s papers.

McCay returned to the paper, he was called into the office of Brisbane, who was not only Hearst’s top columnist, but also his chief editor and advisor. “Mr. McCay, you’re a serious artist, not a comic cartoonist,” Brisbane said, referring to Winsor’s highly regarded work drawing political cartoons. He wanted McCay to give up the distractions and focus on drawing “serious cartoon-pictures around my editorials.”

This was devastating news. Not only would it mean less time for Winsor to pursue animation; Brisbane was an angry blowhard and a horrible boss, a man who snooped through the trashcans of his subordinates looking for signs of disloyalty. A predecessor of overheated cable news pundits, his was an anger that was translated into a yearly salary of $260,000 through a hysterical style of spouting “half-baked theories” and “half-remembered fact and fiction,” according to one of his biographers. Winsor’s art, on the other hand, was whimsical and dreamlike, almost the exact opposite of Brisbane’s angry diatribes, which carried the tone of a man trying to win an argument by shouting louder than everybody else in the room. By assigning McCay to Brisbane’s desk, Hearst was clipping his wings.

William Randolph Hearst didn’t initially see the profit in animation, and thus didn’t pay it much mind. But he always appreciated the value in illustrated cartoons, which had helped him build his media empire. He understood that, in a nation of immigrants who couldn’t always read English, cartoons often had more influence than articles, and therefore more power. This had long been understood by politicians like Tammany Hall chieftain William “Boss” Tweed, who once said, “I don’t care what the papers write about me. My constituents can’t read. But, damn it, they can see the pictures.” (Ironically, when Tweed escaped jail in 1876, he was arrested by an official who recognized him from the caricatures in Harper’s Weekly, drawn by Thomas Nast.)

When Hearst entered the newspaper business, one of his earliest hires was a teenage cartoonist named James Swinnerton, known as Jimmy to some and Swinny to others. Swinny had previously worked at a racetrack, but joined Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner in 1892 after realizing that he preferred drawing to gambling. After spreading upcoming comic strips on the floor of Hearst’s office, Swinny would then watch as Hearst walked among them, enthusiastically scribbling notes in the margins. After Swinny’s hiring, Hearst continued acquiring top talent, often by poaching it away from his competitors. In 1898, Hearst hired Richard Outcault, one of the first cartoonists to use speech balloons, from his rival and fellow newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer. Done in order to acquire Outcault’s popular “Yellow Kid” character, the acquisition inspired the term “yellow journalism,” describing the newspaper industry’s breathless competition for market share, sensationalism, and profit. Hearst then rubbed Pulitzer’s nose in his victory by printing “eight pages of iridescent polychromous effulgence that makes the rainbow look like a lead pipe. That’s the sort of a Colored Comic Weekly people want—and—THEY SHALL HAVE IT!”

As moguls battled over their talents, newspaper artists were well aware of their bargaining power. Sometimes, they used their cartoons to send subtle messages to their employers. In 1911, while still working for James Gordon Bennett’s Herald, Winsor McCay had been frustrated over his pay and what he considered a lack of creative freedom, so he slipped a secret message to Bennett into one of his Little Nemo in Slumberland strips. “Now we can do and go wherever we please!” Nemo squeals as he tours different American cities in an airship. Soon thereafter, McCay signed his contract with Hearst.

A bidding war between Joseph Pulitzer and William R. Hearst to acquire The Yellow Kid comic strip character would inspire the term “yellow journalism,” referring to the industry’s breathless pursuit of sensationalism.

A year after curtailing Winsor’s vaudeville appearances, Hearst began to change his low opinion of animation. John Bray’s and Raoul Barré’s fledgling studios had begun releasing regular series of animated cartoons, some based on newspaper comics, and Hearst realized how animation could boost the popularity of his own strips, which included Krazy Kat, Happy Hooligan, and the Katzenjammer Kids. In 1915, Hearst started his own animation studio, International Film Service (IFS), and hired one of Barré’s animators, Gregory La Cava, to run it. The cartoons weren’t particularly well drawn and the studio ultimately lost money, but this didn’t matter to Hearst so long as they increased the popularity of his newspaper comics and helped sell papers. Losses were written off as an advertising expense. The studio was shuttered a few years later, after Hearst decided it was no longer worth the effort.

McCay never worked for IFS. A cartoonist of his skills was far more valuable at the newspaper. Nor would he have wanted to work there; the work primarily consisted of simple line drawings and gag humor, and wasn’t up to McCay’s level. Instead, he continued toiling away on artwork for Arthur Brisbane’s ghastly columns. But his thoughts remained on animation and dreaming up his next big project.

Winsor McCay opened his morning newspaper on May 7, 1915, to read that a German U-boat had torpedoed the British ocean liner Lusitania. The ship sank to the bottom of the Atlantic in eighteen minutes, its four giant smokestacks hissing and sputtering as they slipped underneath the sea. No pictures of the tragic sinking existed; there were images only of the aftermath: bloated bodies, tangled in seaweed, washing up on the shores of Ireland, many of them children.

For days, talk of the sinking filled New York, rattling the windows of cafés and diners. Americans wondered when they would get involved in the war. Speculation filled the newspapers but was noticeably absent from one man’s papers: those of William Randolph Hearst, a staunch isolationist. This bothered McCay, who thought the German aggression needed to be confronted. The only country Hearst did support attacking was Mexico, but this was probably only because Pancho Villa had once looted Hearst’s vacation house in Chihuahua, and Hearst likely wanted revenge. Hearst certainly didn’t want to enter a war to assist the British, whom his papers still sometimes referred to as “redcoats.” Two days after the Lusitania sank, Arthur Brisbane argued that the ship “was properly a spoil of war, subject to attack and destruction under the accepted rules of civilized warfare.”

McCay was still working for Brisbane, providing illustrations for his off-kilter rants. The drudgery was wearing on him, making his work flabby and less lively. He often disagreed with Brisbane and particularly disagreed with him about the Lusitania.

Despite his being in the rotten position of having to work for an unpleasant boss, Winsor’s situation was slowly improving. Hearst had loosened his moratorium on cartoonists holding side jobs, allowing McCay to take Gertie the Dinosaur back on the vaudeville circuit, although with some restriction on how much he could travel. Back in the saddle, he began thinking about new animation projects to tackle, his thoughts constantly returning to the sinking of the Lusitania. Since no photographs had captured the dramatic moment, a cartoon of it might help people better realize war’s human cost.

In July 1916, McCay was in Detroit showing his cartoons at vaudeville theaters when he announced his next project. “Imagine how effective would be cherubs that actually fly and Bonheur horses that gallop and Whistler rivers that flow!” he told a gaggle of reporters, reminding them of animation’s grand possibilities. Whenever he talked about the new art form, he liked referencing fine art, the kind of art done on canvas with oil paint. He then reminded the reporters of the ways animation was evolving, thanks to many innovations introduced by men like John Bray and Raoul Barré. McCay explained that he would be using some of those innovations in his next project. “I am now working on a film which will show the sinking of the Lusitania,” he announced. Then he added a dramatic flourish: “The film will revolutionize cartoon movies.”

McCay needed two years to make The Sinking of the Lusitania. He had help from his assistant, John Fitzsimmons, and another friend, William Apthorp Adams, who was a descendant of John Adams and one of Winsor’s cartoonist pals from his Cincinnati days. Because of McCay’s newspaper duties, the men could only work part-time and the task quickly became daunting. It required approximately 25,000 separate drawings even though the film was only a little over ten minutes long. To get the atmospheric effects he wanted, McCay experimented with elaborate shading techniques and ink washes to capture the complicated movements of drifting smoke and churning water. Each frame was its own little painting.

A signed cel from Winsor McCay’s The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918).

“Winsor McCay’s Blood Stirring Pen Picture—the World’s Only Record of the Crime that Shocked Humanity!” the movie poster read when the film debuted in July 1918. Other animators were awed by how the ink washes had given it an impressionistic effect, while fine cross-hatching and intentional splatters added to its impact by providing the feel of a newsreel documentary. On-screen, the Lusitania glided silently across the black water under a silver crescent of moonlight; the breathtaking visuals, alternating shots of close-ups and pans, done at varying speeds, were far more advanced than the camera work of much live-action cinema being done then. After taking the audience underwater to glimpse fish darting away from the bubbly wake of the German torpedoes, McCay ended with images of the passengers’ heads bobbing on the waves. For the finale, a mother slips beneath the water, struggling to push her infant to the surface.

The Sinking of the Lusitania was instantly deemed a masterpiece, although it didn’t have the full cultural impact McCay had wanted. He originally envisioned it as a call to arms, inspiring Americans to join the war in Europe, but millions of American soldiers were already fighting in France by the time the cartoon finally debuted. Thus, The Sinking of the Lusitania served more as a memorial, solemn and brooding, rather than as a battle cry. It also set a high-water mark for other animators to reach; its movie poster boasted that it was “the picture that will never have a competitor!”