Читать книгу Wild Minds - Reid Mitenbuler - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 7

“How to Fire a Lewis Machine Gun”

In the years after World War I, Max Fleischer found working for John Bray frustrating. Max was still one of Bray’s best employees, but Bray’s interests had shifted. He was no longer interested in making the kind of comedies that inspired Max; he was now focused on training and industrial films.

During the war, Bray saw the contracts going to defense contractors and smelled a lucrative new opportunity. The military would need training films, and animation offered a way to illustrate certain concepts much better than live action could. After meeting with Army officials at West Point, Bray procured a contract to make the films they needed, many of which would rely on Fleischer’s rotoscoping process. When the Army then tried to draft Fleischer, Bray asked, “How can I make films when you draft all my men?”

Bray had a fair point, so the Army agreed to an arrangement. Fleischer was relieved of regular service and sent to “Fire School” at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he would supervise the production of training films made there. A dusty scrubland surrounded by even dustier scrubland, Fort Sill was a far cry from New York, but Fleischer didn’t seem to mind. Clad in a custom-tailored wardrobe of drab olives and muted browns so he would appear at least somewhat Army-like, he directed films with titles like How to Operate a Stokes Mortar, How to Fire the Lewis Machine Gun, Submarine Mine Laying, and How to Read a Contour Map. After the war ended, Fleischer returned to New York and convinced Bray to hire his brother Dave, who had been stationed in Washington, D.C., making training films for the medical corps. Able once again to focus on comedic cartoons, the brothers revived Dave’s old clown character and began working up a new series, Out of the Inkwell (although the character would go nameless for several years, by 1924 he would regularly be referred to as Koko, or sometimes Ko-Ko). A mix of live action and animation, each installment of the series began with Max sitting at a drawing table, bringing Koko to life and then setting him off on a series of misadventures in the city. The series was released on a bimonthly schedule starting in 1919.

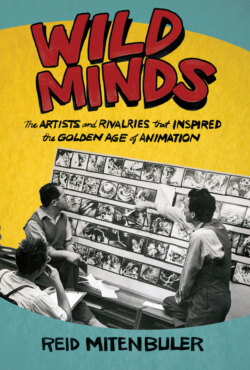

Max Fleischer filming How to Read a Contour Map, one of many military training films he made during World War I.

Although not as popular as Felix—a difficult feat to match—Koko quickly became one of his few notable competitors. Like Felix, he possessed a unique personality, much more than just a simple cartoon automaton performing simple gags and stunts. His films possessed a reflexive nature not seen in other cartoons; he was always aware that he was living as a cartoon, made of pen and ink. This concept, reflecting his creators’ sly self-awareness, thrilled audiences. The clown was “a living example of what can be accomplished by hard work and concentration,” according to Moving Picture World. The New York Times was also impressed, proclaiming that “Mr. Fleischer’s work, by its wit of conception and skill of execution, makes the general run of animated cartoons seem dull and crude.” Fleischer was pleased by the attention but was nagged by a question raised by another Times reviewer: “Why doesn’t Mr. Fleischer do more?”

Model sheet used by animators to standardize the appearance, posture, and gestures of Koko the Clown.

Max did want, very badly in fact, to do more. He tried to convince Bray that, even though Koko was already a star, he could be so much bigger—some theaters had even started advertising him on their marquees, which almost never happened for the opening shorts; it was meant only for main features. But Bray wasn’t interested. His success with military training films had convinced him that educational material was the future of animation. Such films might not have been as sexy as entertainment films, but they did offer steady and dependable revenue from government and corporate contracts. This was important to Bray because he was by now having financial difficulties. His expansion plans had included a production and distribution contract with the Goldwyn Company, a contract worth roughly $1.5 million, which required that he release more than 150 reels of film a year, a number he had trouble reaching. By 1921, he faced numerous legal threats for contractual breaches related to nonperformance and lack of delivery. He would ultimately survive his precarious financial predicament, but not by producing the kind of films that interested the Fleischers. By 1928, he would shutter his entertainment division in order to focus on military films, which he would make well into the Cold War. He would also become the auto industry’s biggest provider of training films.

Bray’s new priorities prompted the Fleischers to leave and start their own studio in 1921. Named Out of the Inkwell Films, Inc., it had humble beginnings, operating out of a dingy basement apartment at 129 East 45th Street, just beneath the groaning floorboards of an old brothel.

How Max Fleischer got the financing to start his own studio was never quite clear. Judging by the colorful stories passed around about the family’s gambling habits, this murkiness might have been intentional. Not only was Essie Fleischer a regular at the racetrack, she liked organizing poker games, where she smoked cigars and pipes alongside the men and ordered her scotch “neat—no water, no soda, no ice, just scotch,” according to her son. From what were probably gambling winnings, she had given Max the money he needed to finish designing his rotoscope, and perhaps a similar arrangement was in play with the new studio. Perhaps not coincidentally, Dave Fleischer won $50,000 gambling on horses just before the Fleischers left Bray. Whatever the case, the Fleischers were never particularly clear about their financing.

One of Max Fleischer’s children later speculated that some money might have come from a distributor named Margaret Winkler. A scrappy immigrant from Hungary, Winkler got her start in the film industry in 1912, at the age of seventeen, working as a secretary for Harry Warner of Warner Bros. When Warner decided to shed the studio’s cartoon distribution deals in the early 1920s—he was not yet convinced that cartoons had staying power—he gave them to Winkler. Not only did he admire her competence, but her bicoastal contacts—made during the years when Warner Bros. was expanding its business into California—were an important qualification for a good distributor. Soon she had worked her way into a deal distributing the Felix cartoons, the most popular series on the market. Signing a distribution agreement for the increasingly popular Fleischer cartoons, which the brothers were trying to distribute themselves, was likewise a shrewd business move.

The arrangement with Winkler was also useful for Max Fleischer. Good distribution could make or break a film’s success, and a skilled distributor like Winkler was crucial. The job meant navigating a complex set of rules known as the “states rights method,” a corrupt and murky system that guided how films were distributed. Under this system, film prints were first sold to brokers, who then distributed them to theaters in a given territory, oftentimes underreporting their numbers and skimming from the percentage owed to the producer. In other cases, brokers sometimes made illegal copies of a film, distributed those, and pocketed the full take. A successful distributor like Winkler had to be part accountant, part bouncer. Her colleagues noted that most of her success was because of her “quick mind,” though others added that her “short temper” also proved handy.

Winkler was also one of the few women in the industry with any real power or influence. Because she knew that some people were wary of doing business with a woman, she used the initials “M. J.,” in “M. J. Winkler Productions,” as a way of hiding her gender (The “J.” in her initials had been made up since she didn’t actually have a middle name.) “How did you do it?” a newspaper reporter once asked Winkler in 1923. “Are people surprised to find out that M. J. Winkler Productions is owned by a woman?”

Winkler would smile politely at such questions, well aware of the obstacles impeding women in her line of work. “I think the industry is full of wonderful possibilities for an ambitious woman,” she said. “And there is no reason why she shouldn’t be able to conduct business as well as the men.” Some men were threatened when they first met her, she explained, “but they got over it.”

As the Out of the Inkwell series grew in popularity, the Fleischers upgraded their studio in 1923. The space beneath the funky old brothel was exchanged for the spacious sixth floor of 1600 Broadway, an impressive tower of elegantly curved brick archways located near the bright lights of Times Square. The staff numbered nearly two dozen now, and included the important addition of Richard “Dick” Huemer, an animator who had previously worked for Raoul Barré. Huemer helped redesign Koko and conceptualize for him a pet dog named Fitz, a sidekick whose main role seemed to be getting Koko into trouble.

As the studio grew, Max and Dave settled into a division of labor. Even though Max’s name was bigger than Dave’s in the credits, the studio’s cartoons reflected Dave’s personality equally. Max handled a fair amount of creative work, but also most of the back-office administration: phone calls, payroll, meetings organized around lunch. Dave’s responsibilities were almost entirely creative: directing cartoons, initiating story ideas, dreaming up gags. His informal directorial style usually started with a general idea upon which the staff would riff—he avoided storyboards and most other forms of organized structure. Individual animators were free to add pretty much any idea, so long as it got laughs. In this way, what the films lacked in gloss they usually made up for in energy. The studio animators also reduced their use of the rotoscope, preferring instead to let their imagination steer the action.

In 1923, shortly after moving into his new studio, Max Fleischer decided to take animation in a new direction. This didn’t mean drastic changes to the Out of the Inkwell series, which had settled into a nice groove; it meant exploring ideas that weren’t strictly comedy.

Ever since Albert Einstein published his general theory of relativity in 1915, Fleischer had been fascinated by it. The theory had revolutionized how scientists thought about space and time, but very few laypeople understood it. It was just the sort of puzzle Fleischer had once worked on as art editor of Popular Science magazine, and he thought animation might help explain the concept.

He started by enlisting the help of Professor Garrett P. Serviss, a science writer for the New York American whose mind “worked at the speed of light,” Fleischer liked to joke. Soon after the two men began working together, however, they clashed over how best to translate Einstein’s complex ideas. Serviss was a literal-minded scientist, uncomfortable with making the leaps of faith that good storytelling often requires. Fleischer was sympathetic, but also knew that audiences become confused by too many details. After Fleischer suggested using a title card that read, “When you see the stars twinkle,” Serviss pounded his fists on the table in angry disagreement, arguing that stars don’t actually twinkle, and that such effects are actually just an illusion.

Fleischer pleaded with Serviss to see things like a storyteller. “Poets make pictures,” Max explained. “They paint with words, but give you a mental picture nonetheless, and since the world has poets and people like poetry, in my opinion it is correct to say that the stars ‘twinkle’ as I think they do.”

Serviss rose from his seat and continued pounding the desk. “I will not go any further, nor will I permit the use of my name in connection with a gross misrepresentation of scientific fact!” he roared. “It’s too bad that after sixty years of scientific writing for the public, here comes Max Fleischer trying to tell me what is right or wrong to say.”

Fleischer gave Serviss a few days to cool off, then tried again. People can reread confusing sections of articles, he calmly explained, but they have a harder time rewatching films. “We must tell our audience these facts in a language they understand the first time,” he said. Serviss finally relented but refused to watch the “stars twinkle” segment whenever it came up on the screen. “It amused me,” Fleischer remembered. “But Professor Serviss was a true scientist.”

When Albert Einstein saw the film, titled The Einstein Theory of Relativity, he was impressed enough to write Fleischer a fan letter. Other reviewers were equally positive, lauding the film for staying as simple as possible. “They have wisely confined themselves almost entirely to the more popular aspects of this complicated theory and have not attempted to delve deeply into the sections regarding the fourth dimension and the bending of light rays which Einstein himself is quoted as saying can only be clearly comprehended by about a dozen persons,” a writer from Moving Picture World wrote. Another reviewer was more succinct, writing that Fleischer was “either a man of super-intelligence or just plain crazy.”

Despite the positive reviews, the film flopped. Fleischer thus learned a valuable lesson about audiences: they generally want to be entertained rather than educated, to see a clown fall down an open manhole rather than learn about Einstein’s theories regarding space and time. Fleischer would later joke about the film’s commercial failure. “There were supposed to be only three people who understood Einstein’s theory,” he said. “Now there are four.”

Two years after The Einstein Theory of Relativity, Fleischer was ready to try making another similarly ambitious cartoon. This time, he wanted to tackle the theory of evolution. The papers of the day were full of stories about the Scopes “Monkey Trial,” in which John Scopes, a substitute high school teacher in Tennessee, was accused of violating state laws forbidding the teaching of human evolution in state-funded schools. The case attracted some of the most famous legal names in the country, with three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan arguing for the prosecution, and famed defense attorney Clarence Darrow speaking for Scopes. Fleischer figured the controversy would drive interest in his cartoon, a combination of animation and live action that chronicled Earth’s creation and the advancement of life, progressing from single-celled organisms into dinosaurs, lower mammals, and eventually humans.

When the film debuted, more people showed up to protest than to buy a ticket. During the premier at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, fistfights erupted in the lobby as angry mobs pushed over display cases, scattering shards of glass across the marble floor. Failing to gain wide release after that, the film failed financially. “The picture made an attempt to merely illustrate Darwin’s theory and not to teach the theory,” Fleischer would later explain defensively.

Throughout the rest of his career, Fleischer would continue to occasionally dabble with similar conceptual material. But he would also remember what kind of cartoons paid the bills. In 1924, the studio began releasing Song Car-Tunes, a series that used an animated bouncing ball over song lyrics to lead audiences in theater sing-alongs. It was a smash hit.

The Fleischers weren’t the only ones to leave Bray’s studio for more creative endeavors. And though they were the most well known of the Bray alumni, they weren’t the most financially successful. That honor would go to Paul Terry, whose unique path would lead somewhere very different. Many considered his cartoons some of the worst ever, although he made a fortune from them.

In person, Terry was charming and witty, describing himself as “a dreamer, more or less.” Around 1904, he dropped out of high school and got a job working with the cartoonists at the San Francisco Chronicle. He later headed east after landing a cartoonist job with the New York Press. After seeing Winsor McCay present a screening of Gertie the Dinosaur, he decided to become an animator.

Two formative experiences guided him. The first came in 1915 as he tried to sell a cartoon to famed film mogul Lewis J. Selznick, who watched Terry’s film, paused for a second, then offered him a dollar a foot for the finished product.

“Mr. Selznick,” Terry answered, “the film I used cost me more than a dollar a foot.”

“Well,” Selznick replied, “I could pay you more for it if you hadn’t put those pictures on it!”

The second experience came after a distributor told Terry that he used his cartoons to clear people out of their seats after the feature. Terry wasn’t even sure if the distributor knew that he was the creator.

From that point on, Terry thought of cartoons strictly as a commodity, not an art. The business became, to him, entirely about cool logic, math, and figuring out the business angles. During his stint working for John Bray, he improved his ability to draw quickly and efficiently, two important skills. He left in 1917 after selling a cartoon with his original character, Farmer Al Falfa, to the Edison company. After World War I—he animated training films for combat surgeons—he struck out on his own. Then, in 1920, Terry received a call from a young actor-turned-writer named Howard Estabrook, who pitched him the idea of a cartoon series based on Aesop’s fables. Terry had never heard of Aesop or his fables, but he was intrigued when Estabrook said it might be profitable.

Terry also liked how the fables featured animals. In many ways, animals made better characters than humans, as Felix’s rising popularity was starting to prove. “When you do something with an animal, it’s unconscious satire, and it seemed to be more sympathetic,” one of Terry’s colleagues would recall. People who act like animals get shunned, but animals that act like people can become immortal. Animal characters also reduced the possibility of offending audiences through ethnic stereotyping, thereby helping them gain wider national appeal, as well as avoid the New York in-jokes commonly found in most other cartoons of the time. Anthropomorphized animals could still be offensive, but started on relatively safer ground, thus helping boost their reputation with distributors and theater owners.

Terry organized his studio the way a factory owner might lay out his plant, with about twenty cartoonists working at desks lined up in rows. Like Bray, he divided the labor into specific tasks, as in an assembly line, to create a hierarchy of labor that was by then becoming an industry standard. The best artists drew only “extreme” poses—that is, poses that anchored the major points of movement in a character’s action. A second tier of artists, known as “in-betweeners,” would then trace in all the drawings between the extremes. These in-between drawings were considered easier to draw, since more tracing was involved, and thus freed up the better artists to focus on harder tasks where their skills were most needed. Finally, a bottom tier of assistants completed the inking, a more menial task that involved filling in the outlines drawn by the others. When labor was delegated this way, animation could be done more quickly and efficiently.

Terry treated every aspect of a cartoon like a variable in an equation. “He kept a file of A gags, B gags, and C gags,” animator Art Babbitt remembered. “The A gags would get a hilarious laugh, the B gags would get a friendly response, and the C gags were not so successful.” Terry mixed and matched the components like a dealer shuffling a deck of cards. Drawings were recycled from other cartoons, while shortcomings were often hidden by speeding scenes up or making them more violent.

“It didn’t matter what the hell the story was,” Babbitt said. The plots featured characters like “Lucky Duck” or “Rufus Rooster,” and were often just random series of non sequiturs. They rarely made sense, and the “lessons” at the end of each fable rarely had anything to do with the story. “A man who cannot remember phone numbers has no business getting married,” read one. “He who plays the other fellows game is sure to lose,” read another, which also highlighted the studio’s loose control of grammar.

“We take any idea that sounds like a laugh,” Terry told the New York Times about his business strategy. Babbitt put it another way: “What we were doing was just crud . . . Terry didn’t care—he was out for the bucks.” Terry, whose studio would remain one of the most profitable in the business well into the 1950s, would freely admit this as well. Another animator remembered applying for a job with him and being told, “We do shit here, compared to the rest of the business, but it makes me a lot of money. If you don’t like to do shit, don’t ask for a job.”