Читать книгу The Book of Israela - Rena Blumenthal - Страница 7

3

ОглавлениеWhen I returned to the office, I found a fuming Penina Mizrachi beached outside my door. I suggested to Penina, who I now remembered as the fat woman with the garishly dyed and braided hair, that we reschedule for another day, but she would have none of it. Once in my office, she perched on the edge of the patient’s couch, clutching her oversized handbag in her lap, and launched into a long, whiny complaint about the ways in which I—like her husband, grown children, and a random assortment of neighbors—didn’t afford her the respect she was due. She had been on time for her appointment, as she always was, and had seen me ever-so-casually slip out of the waiting room. Why was her time not as important as mine? I might have answered that she, unlike even minimally functioning people like myself, had no job and no schedule to keep, and what difference did it make if she spent her time in our waiting room or sunk in her couch staring at celebrity talk shows? But I held my tongue and watched her substantial bosom heave up and down with the weight of her lot, wondering at the effort and expense and poor judgment that had culminated in her odd coiffure, listening intently to the squeaking sound her breath made on the rare occasions when she took a chance and paused. She needn’t have bothered, as I had no intention of interrupting her numbing monologue. Long ago she had married a man who was unabashedly in love with another woman and had kept the affair going through all the years of their marriage. Saddled with a slew of unruly kids, she had never had the confidence or self-respect to walk out on him. Listening to her, I found myself longing for Nava, thinking about her lithe body and ropy neck, the proud way she angled her head in public. Nava had dignity, self-respect—she wouldn’t put up forever with a no-good philanderer. I was suddenly filled with an overwhelming sense of loss. What had I been thinking? Nava was nothing like this pathetic specimen, this Penina Mizrachi, who had let herself grow fat and lazy and reconciled to a lifetime of neglect and humiliation. I held tight to my rising grief, my face frozen into concerned listening mode, my sympathetic grunts modulating to the wavelike heaving of Penina’s chronic, languishing despair.

When the session was over, I watched her dutifully get in line at the reception desk to confirm her next visit. I had barely heard a word she had said, yet she was visibly calmer. Was she really so lonely that even this pretense of caring companionship made her life more bearable? I rummaged through the piles on my desk for her long out-of-date chart, then stared at it a while, wondering what I could possibly write about this session. “Patient continues to have symptoms of depression and anxiety. Patient continues to feel unappreciated and unloved. Patient continues to lead a useless, pathetic life. Patient continues to bore husband, children, and therapist to distraction.” I tossed the chart onto the floor in disgust.

The afternoon dragged on, patient after desperate patient. Jezebel was right that the intifada was causing a dramatic increase in the demand for our services, but I wasn’t nearly as confident as she was that our role in the midst of this social dysfunction was entirely benevolent. Yes, we could sometimes provide superficial relief through medications, or even therapy, but weren’t we just enabling all the feckless politicians on both sides who allowed this insanity to continue? My 3:00 patient was typical—an eight-year-old boy who had stopped speaking and developed violent outbursts after witnessing the Sbarro restaurant bombing in August. More than seven months later, he still hadn’t said a word. His mother, frantic with worry, was herself suffering from insomnia, chronic nausea, and other post-traumatic symptoms, which her psychiatrist had been trying for months to alleviate through the right combination of brightly colored pills. But wasn’t hers a perfectly normal reaction to watching a pizza parlor in downtown Jerusalem, on a hot summer day, suddenly explode into flames?

At 6:00 I thought I could finally call it a day, but the receptionists had wasted no time scheduling in extra patients, vengefully taking advantage of my predicament. They had assigned me a new patient, of all things, to the 6:00 hour. I hadn’t done an intake in months—if she showed, it would mean reams of paperwork. And, as Jezebel had made abundantly clear, I’d have to complete it, too.

I petitioned whatever gods might be up there for reprieve, but being the confirmed atheist I was, my plea to the heavens was duly unheard. About ten minutes into the hour, just after I had successfully flung a rubber band over the engraved, ornamental quill pen Yudit had bought me for my forty-fifth birthday, a woman barged into the room. Why hadn’t the receptionist called to tell me she was here? I flung my legs off the desk, knocking a few more charts onto the floor, but she didn’t notice a thing. She was in full story before I’d even stood up.

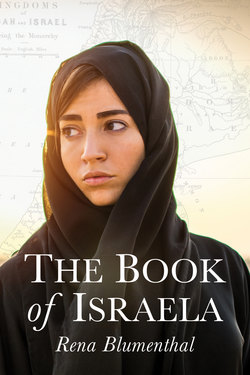

“Dr. Benami? Thank God, I finally have someone to talk to.” She was untangling herself from a huge, fringed shawl that wrapped her head like a mummy, talking all the while. “You can’t imagine what it’s like being followed all the time. I can’t take it anymore.” The tears were already starting to spring up—another desperate, weepy broad.

“Excuse me, but did you sign in with the receptionist? I’ll be needing the intake forms, and—”

“I was so late, I didn’t want to wait in line,” she said impatiently. Her eyes flicked around the room and finally landed on me, round and dark. “His crazy friends are stalking me again. I have to dodge them whenever I leave the house, taking roundabout routes through back alleys. That’s why I’m late wherever I go, but otherwise they follow me and harass me, you have no idea what it’s like.” She paused to push a long strand of curly black hair out of her face, fixing me with a stare. “You have to forgive me, Doctor, and you such a busy man. I know, they told me—the chief psychologist! They must realize what a tough case this is—everyone in Jerusalem knows about me.” And with this she sunk into my recliner, the tears beginning to gush.

“I’m afraid you’re sitting in my chair. The patient usually sits—”

“I know how busy you are, Doctor, but you have to help me!” She launched into another tirade but was so blubbery with tears I couldn’t understand a word. Grandiose, paranoid, hysterical—it was going to be a long hour. I reconciled myself to the stiff couch, a stranger in my own office, noticing that the piles of charts on my desk looked particularly precarious from the patients’ angle. Probably not the most reassuring sight—I made a mental note to at least arrange them into neat stacks. The woman was going on and on, sniffling and blowing her nose, complaining about her husband. Another miserable, tortured relationship. I’d heard the routine countless times from every possible angle. But this was an intake, I reminded myself; I’d have to settle her down and get at least a few details if that paperwork would ever get done. I could always pick up the forms from the receptionist at the end of the session.

“Uh, Mrs. . . ”

“Tzur. But please, call me Israela. Everyone does.” She looked up at me, her eyes filled with tears, muddy brown pools of desperation.

She would have once been an olive-toned beauty. She was still attractive, but her face was prematurely etched with worry lines. Mid-thirties, I’d guess. Slim, still dressing like a hippie, in bangles and gold chains and flowing skirts, layers of flouncy material, laced leather sandals. I wondered if she shaved her legs under those billowing skirts; these gypsy types often didn’t. She had dark, curly hair, long and wild, glinted with silver streaks. Her eyes were her most striking feature, large and soupy. And she was built, with full breasts straining at her white, cotton blouse. But there was something peculiar about the way she held herself, I couldn’t quite put my finger on it . . .

“Doctor, what do you think I should do?” She was staring at me intently.

“Well, Mrs . . . uh . . . Israela, I think it’s way too soon to start talking about solutions. I’ll need to know a lot more about you before I have any idea how I might be able to help. This is an intake session, which means we’re here to gather lots of information: what the problem is, when it began, your early history. Based on what I learn, we’ll formulate a treatment plan. I know you’re upset right now, but why don’t you see if you can tell me in a few words what problem brought you here today.”

She reached an arm out to pluck another tissue from the box, then grimaced in pain, rubbing the side of her neck with the other hand.

“Is something wrong?”

“The muscles go into spasm when I’m upset,” she said, massaging her neck with her left hand as she dried her eyes with the right. “My husband complains about it all the time. He thinks I do it on purpose, for sympathy, or as an excuse not to listen to him. But that’s totally unfair. It just happens whenever I get upset.”

This threatened to release a new wave of sobs. I went to my desk, picked up a notebook and pen, and sat back down on the edge of the couch. “Israela,” I said in a firm tone. “Why don’t you tell me, as clearly and succinctly as you can, what makes you seek treatment at this time.”

She calmed down instantly. The paper and pen was a great trick, I’d found. Helped even the most histrionic women focus, at least for a little while.

“Well, like I was telling you, my husband, he’s the center of my life. He’s everything to me. But the truth is, he doesn’t treat me very well.”

“In what way?” I jotted a note, then let the pen hover over the paper for effect.

“It’s not his fault, really. He’s very insecure, that’s all.”

“And how does he show that insecurity?”

Her eyes were darting around the room, the telltale sign of a battered wife. I’d bet my last shekel she was another bruised-up woman about to protect her beloved abuser.

“Well, for one thing, he’s very secretive. He’s almost never home, but even when he is, he sneaks around like a thief.” She sighed deeply. “He doesn’t like showing his face.”

“He’s that shy?” I asked.

“Oh no, not at all. He’s just . . . well . . . sensitive.”

Yeah, right. So sensitive he’d probably kick her around the room if she happened to be standing in the way.

“I see. And does he show this ‘sensitivity’ in other ways as well?”

“Yes, well . . . he can be very jealous. He’s always imagining that I’m having affairs. He even brags about how jealous he is to his friends, as if it were proof of how much he loves me.”

I made my voice soft and sympathetic. “Does he threaten you?”

“Well, sometimes, I guess.” The tears were welling up, but this time she fought to keep them down. “Yes,” she whispered, “he threatens me a lot.”

“What does he threaten you with?”

“Oh, terrible things. How he’ll hurt me, humiliate me, destroy our house. But not directly, he never threatens me directly.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Well, like I said, he’s hardly ever around. Months can go by and not even a word from him. He doesn’t call, doesn’t tell me where he is. So he sends messages, through his friends, the ones who are stalking me.”

“Threatening messages?”

She nodded, absentmindedly rubbing her neck.

“Have you ever reported these stalkers to the police?”

“Oh, no, of course not. They’re his friends; they’re just trying to help him. And they’re doing it for my own good, I know.” She lowered her eyes, a delicate crease forming between her eyebrows.

“Has he ever carried out any of his threats? Has he ever gotten violent with you?” I asked gently.

“Well, sort of . . . But none of this is really his fault! I haven’t been a good enough wife. I haven’t been the kind of wife he wanted.”

“That would hardly give him the right—”

“I know.” It was barely a whisper. We sat a few moments in silence.

“When’s the last time you saw him?” I asked.

“Oh, my goodness, it’s been such a long time. I’m not even sure. Maybe a year? Or even longer.”

That was straining credulity. “You haven’t seen or heard from him in over a year? Are you sure he’s OK?”

“Of course he’s OK,” she said. “His friends see him all the time.”

There was something very odd going on here. I needed a new line of inquiry.

“What kind of work does he do?” I asked.

“He’s a . . . an entrepreneur.”

“What do you mean?”

“Oh, it’s kind of hard to explain. He’s always busy with one thing or another. Got his finger in a million pies.” She smiled weakly, as if to apologize for the obvious evasion.

The husband was starting to sound like a shady character. I wondered if he might be part of the Israeli Mafia. Sometimes these Mafia types had to go underground for long periods of time, keeping their whereabouts unknown even to their wives. That would explain the lackeys with their violent threats. But was she covering up for him, or did she really not know? Now I was genuinely curious.

“Do you have any idea where he’s been this past year?” I asked.

“Not really. Even before that, he was never around much. He has an office in the house, with a separate entrance. Sometimes I think I hear him shuffling around down there, but I’m never sure. The office has a couch, but I don’t think he ever sleeps there anymore. Maybe his friends put him up. He must hang around with them a lot; you should see how they worship him.” She looked embarrassed. “Like I said, I don’t really know where he is.”

“Do you think he may have another woman?” I asked gently.

She broke into a pained laugh. “Him? With another woman? Don’t be ridiculous. I’m the only love of his life.”

Even for a battered woman, that level of denial was extreme. I’d seen my share of absentee husbands, usually with a mistress or two in town, sometimes a slew of kids, and the wife sitting at home all innocent and surprised. Did he really sneak into his office, send threatening messages? It seemed much more likely that the guy had set up a whole new life, that she imagined his little visits, had made up the whole story about the stalking to convince herself that she was still married. Could an intelligent woman really be so blind?

And she did seem intelligent. I’d heard a lot of bizarre tales in my time, but something about her had caught my attention. There was the sharp, penetrating way she looked at me, even through her tears, that was disconcerting. I wondered if she was trying to hear my mind’s commentary, to see through my pretense. It was a question that usually didn’t concern me much, but I was feeling a little sensitive myself these days. It occurred to me that from the couch there was nothing much to look at other than the mess of charts; from the recliner I could always keep an eye on my reflection in the glass of the window. Without those reassuring peeks at my professional mien—the gently receding hairline, strong chin, and wire-framed glasses that made me look distinguished, even professorial—I felt, instead, naked and exposed.

“Israela, given the fact that your husband hasn’t been around for so long and that he has this violent streak, I’m not clear why you would want to stay in this relationship. You could claim desertion, or abuse—file for divorce, start a new life.”

“Oh, but I’ve given you such a terrible impression of him! He loves me so much! And he’s the center of my life, he’s everything to me! And we’ve been married such a long time. You’d really need to hear the whole story. This isn’t a marriage one gets out of lightly!”

“One never gets out of a marriage lightly,” I said, in my reassuring, doctor voice. It was the party line, but of course it wasn’t true. Nava had tossed her wedding ring into a coffee cup, and poof, she was out. I wondered again what she would think listening to Penina or Israela, the disdain she would hold for the multitude of women who remained loyal and committed to men who abandoned and abused them. At least I’d never disappeared for months or gotten violent. Why didn’t Nava appreciate what she had in me?

Israela was staring at me, a curious, almost bemused, look on her face.

I snapped myself back to my professional bearing. “Israela, it sounds like this has been going on for a long time. I’m still not clear why you’re seeking treatment now. How do you think therapy will be able to help you?”

She leaned forward in the chair. “You’re not the first person to tell me I should divorce him, forget all about him. All the neighbors say the same thing. But I can’t. I miss him so much. You can’t imagine how awful it is for me.”

“But you haven’t seen or heard from him in over a year . . .”

“I can’t leave him!” she cried. “He’d be lost without me. I can’t destroy him like that after all he’s done for me! And I’d be lost without him. He’s the one who rescued me from my horrible childhood, the one who gives my life meaning and purpose. I’ll never divorce him. Do you think you can help me? Do you think you can help me be the kind of wife he wants me to be?” At this, she broke into another wave of heaving sobs.

Her reality testing was tenuous at best. The guy was happily shacked up with another woman, had practically forgotten she existed, but she couldn’t leave him because he’d be devastated. She never saw him, but he was the only thing giving her life purpose. He’d be lost without her, she’d be lost without him. The thought of even trying to tease out the truth of this bizarre, dysfunctional marriage exhausted me.

I needed more context to figure this out. “Tell me about the rest of your life, Israela. Do you have children? Do you work? What about your family?”

“I have no family; I was an orphan,” she replied. “I don’t have any life outside of him; that’s part of the problem. Like I told you, he’s insanely jealous. I’m not to have any friends, male or female. He would kill me if I ever got a paying job; he doesn’t even want me walking about the neighborhood by myself. And since the intifada started, he’s even more opposed to my leaving the house—he’s terribly worried that something could happen to me. You know that couple who died in Thursday’s bombing on King George Street? They left two orphans, and she was five months pregnant.” She paused for effect. “He totally freaks out whenever something like that happens.”

“Well, of course,” I said, “it affects us all. But we can’t just stay locked up in our homes.”

“I agree, but he doesn’t see it that way. That’s why I wear that enormous shawl. I sneak around like a criminal just to leave the house.” Her voice went down to a frightened whisper. “He’s always been obsessed with the idea that I might be having an affair, but it’s not true. Don’t let them tell you otherwise!”

“Don’t let who tell me otherwise?”

“His friends, they’re everywhere!” She stared out the window like a terrified child, her neck stiff, her shoulders hunched in fear, and I turned to look, half-expecting to see a spying face hanging from the fourth-floor sill. Her voice was rising with panic. “He’ll be furious when he hears I came to see you. Just you wait and see. When word gets out, they’ll come to see you too. They’ll tell you terrible lies about me. Don’t believe a word they say!”

I kept my voice calm and professional. “But if your husband’s never around, how would he even know what you’re doing? And how would these friends of his know—”

“He knows everything!” she shrieked, in a panicked voice. “He sees everything I do! Don’t you understand?”

My heart sank. This was not, after all, some silly woman in delusional denial about an absentee husband; it was, more likely than not, a case of psychotic paranoia. I was getting the sick feeling that the day might end with another forced hospitalization. I kicked myself mentally for allowing myself to be bullied into taking on these new additions to my caseload. Didn’t I have enough trouble? I should have stood up to that bitch and refused. I’d served my time in the trenches, and I was now an administrator. Didn’t that count for anything? How had I gotten myself into this mess?

But even as I groaned at the hours of extra work, my diagnostic wheels were busily spinning. She was extremely dramatic in tone and mannerism, which was not typical for a schizophrenic. But then again, paranoid schizophrenics could surprise you—it couldn’t be ruled out. With such a full range of emotional expression, she certainly didn’t fit the pattern of a paranoid personality disorder. As a matter of fact, the most striking thing about her was her exaggerated affect, which suggested a histrionic or borderline personality disorder. Histrionics could be very loose in their reality testing, but her paranoia was extreme. And what about that neck? Histrionics often somatized their symptoms. Was this a physical manifestation of an extreme mind-body dissociation? Or maybe the whole thing was a manic episode. I needed more information.

But before I could ask another question, she offered her own reality check.

“No, of course you don’t understand, it sounds crazy to you,” she said. “You’re probably thinking you should lock me up. And maybe you’re right! I’ve been stuck in this insane relationship for so long I hardly know what’s real anymore.”

I was relieved to hear her so lucid and self-reflective. It was a good sign. “So you question your own sense of reality?” I asked.

“Sometimes,” she said, her voice soft and pleading. “But if you met him, even for an instant, you’d understand. There’s something about him. Once you’ve been in his presence you never forget it. When you meet his friends, crazy as they are, you’ll see how devoted they are to him, how they love him with all their hearts. Maybe then you’ll get an inkling of what kind of a man he is . . . and he chose me! Of all the women in the world he might have married, he chose me!” She turned her sad, luminous eyes toward me. “You think I’m totally crazy, don’t you?”

Yes, I thought, you’re totally nuts, but something inside me was stirred by her story. For just a moment I could feel her love, shot through, as it was, with terror and wounded pain. Despite my dalliances, I had always been attracted to my wife. I was devastated that she’d thrown me out, already missed the life we’d had together. But now I was wondering: had I ever in my life loved anyone the way Israela loved her husband, or even, for that matter, the way Nava had once loved me?

The feeling was gone in an instant, and I pulled myself back into role.

“What’s his name?” I asked.

She looked away, rubbing her neck as she stared out the window.

“You don’t want to tell me his name?”

She looked back at me. “Oh, no, I would, but . . . it’s just . . . very hard to pronounce.”

“That’s OK. I don’t need to pronounce it.” I picked up my notebook and poised my pen expectantly.

She stared at me a few minutes longer before responding. “I call him Y,” she finally said. “Everyone just calls him Y.”

I let the notebook drop back into my lap. What the hell was she hiding? Was he some kind of notorious criminal whose name I’d instantly recognize? Could it be, even more bizarrely, that she didn’t know or couldn’t pronounce his name? Or, it suddenly occurred to me, was it possible that the husband didn’t even exist?

Our time was almost up and I felt totally disoriented. Maybe it was the effect of sitting on the patient side of the room. Maybe I was just too distracted by my own problems. But I had just sat with this woman for almost an hour with nothing to show for it. I’d gotten almost no essential information, didn’t even have a diagnosis. Maybe I was just getting rusty.

I debated getting an emergency psychiatric consult. The last thing I needed was word getting out that I’d failed to properly treat some psychotic patient. On the other hand, I was on the outs with all the psychiatrists, and any one of them would take perverse pleasure in the shoddy intake I had just done. She was paranoid and delusional, that was clear, but she was also lucid and calm. I decided to take the chance that she could hold on through the end of the holiday. Hopefully, she’d never come back. If she did, I’d be sure and do a full mental status exam, get a proper diagnosis. I decided to let it go.

“Israela, there’s a lot more information I’ll need before I can know how to help you,” I said. “After Passover, I’ll want to get a full life history and a broader sense of your day-to-day life. I’m going to ask the receptionist to schedule you for the first day after the holiday. Will that work for you?”

She nodded, her eyes glistening with new tears. “Passover is a hard time for me—I always miss him terribly during the holiday. I clean the house obsessively, trying to show what a good wife I can be, hoping that will draw him back to me.” We sat in silence for a long minute. “It never seems to work,” she finally said, “but at least the house gets clean.”

I laughed, and she smiled back shyly. A sense of humor was always a good sign.

“Are you sure you’ll be OK over the holiday?” I asked.

She nodded slightly, her whole upper body moving stiffly with the effort. She took her appointment slip and got up to leave, her brow furrowing as she glanced around the room.

“You know, Doctor, you should really speak to the cleaning lady. This office is littered with rubber bands and paper clips.”

She wrapped her head tightly in her shawl and fearfully scrutinized the waiting room before venturing out the office door.