Читать книгу Behind the Hedges - Rich Whitt - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

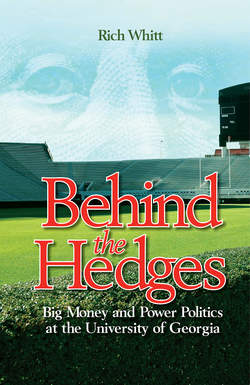

6 Vince Dooley and Michael Adams

ОглавлениеSenior faculty at Centre College say that while president there, Michael Adams had shown a keen interest in the school’s athletic programs. He not only attended games but became directly involved with NCAA matters. That was considered a plus by some members of the Georgia search committee.

Vince Dooley felt certain that he would hit it off with the new president and began to reach out even before Adams arrived on campus, telephoning him congratulations from a hospital bed where Dooley was recovering from knee-replacement surgery. As previously noted, Adams didn’t return the call. When Dooley called again and got through a few days later, the conversation was pleasant with Dooley offering congratulations and Adams saying he looked forward to meeting the legendary coach.

Dooley was satisfied that he would get along fine with the new president. “I’m a person that whoever is given the responsibility as president, my tendency is to go all out to support them,” said Dooley. “I am a good soldier in that respect.”

But Dooley and Adams were soon on a collision course which would reverberate across Georgia. Ironically, it was Adams’s fondness for athletics that led to the dispute, and Dooley now recalls that he received early warnings of trouble ahead.

Shortly after Adams arrived at Georgia, Dooley made a presentation to the athletics board about adding sky suites at Sanford Stadium. Dooley said he didn’t notice, but afterwards Dick Bestwick, the respected senior associate athletic director, commented on Adams’s body language and red-faced expression as Dooley was speaking. Bestwick warned him after the meeting that he had better be wary of Adams.

“That was the first indication that this person was going to be different than any [president] I had dealt with. And I’m glad he was the fifth one and not the second or third one or I might have had a much shorter tenure at Georgia,” said Dooley.

Bestwick later said Adams broached the subject of Dooley’s retirement soon after arriving at UGA. “He asked me when Dooley was going to retire. I said, ‘Why would the king want to abdicate his throne?’” Bestwick said Adams seemed disappointed with that answer.

Dooley recalled another early incident that gave him pause. In the fall of 1998 Uga owner and breeder Sonny Seiler asked Dooley to participate in a “changing of the dogs” ceremony at halftime of an upcoming Georgia football game. Dooley was to remove the collar from the retiring Uga V and ceremonially place it on the new mascot, Uga VI. A week before the ceremony, Dooley got a telephone call from Senior Vice President Tom Landrum saying that Adams wanted to participate in the ceremony. “Landrum said, ‘Mike sees it as a great photo-op.’ I said by all means but I thought to myself that the photo-op was typically political Mike Adams,” Dooley said.

When the cast of characters assembled on the field at Sanford Stadium during halftime, Dooley said he wanted Adams as president to have a prominent part in the ceremony. Dooley suggested that he remove the collar from Uga V and ceremoniously hand it to Adams to then place on Uga VI. Adams nodded his approval of the idea. But when Dooley knelt and removed the collar from Uga V, Adams snatched it from his hand and displayed it for the cameras before Dooley could even stand up. It was a trivial matter, but Dooley was taken aback.

“Up until then, I had not worked for someone whose primary motivation in all things would be so politically self-promoting and ego-driven,” said Dooley. “Prior to that incident, I had many people tell me about the ego and pompous attitude of [Adams], to which I’d paid little attention. But I have to admit that after encountering his display at the changing of the dog, I saw it firsthand.”

Dooley also encountered Adams’s famous temper early one morning in 2002 when he received an irate telephone call at home. Dooley recalls the testy telephone conversation thusly:

“Hello?”

“This is Mike Adams.”

“How are you doing, Mr. President?”

“Not good.”

“What’s wrong?”

“I don’t like what I read in the paper this morning.”

“What did you read?”

“I don’t like reading about an unauthorized stadium expansion.”

Dooley said he explained, as the paper stated, that it was only a preliminary study but Adams replied that neither he nor any members of the athletic board had authorized the study “and this kind of unauthorized action upsets them.”

Dooley said he was by this point in the conversation becoming irritated at Adams’s abruptness. He reminded Adams, who chairs the athletics board, that he had brought the matter up at the previous board meeting.

“I have no recollection of that,” Adams said.

“That’s your opinion.”

“My opinion counts.”

“Mine does, too,” Dooley responded.

After the conversation, Dooley said he researched the minutes of the athletics board and found reference to the study. He had a copy of the minutes hand-delivered to Adams’s office later that morning. Adams never again mentioned the matter even though the two men sat together that very night at a dinner event.

Dooley said he tried to convince Adams that to have good two-way communications between the president and athletic director they needed to meet monthly. The arrangement had worked well with Adams’s predecessors Fred Davison, Henry King Stanford, and Charles Knapp, but Adams rejected the idea.

“I think because I recommended it and it worked well with other presidents he didn’t want that kind of relationship. In fact he told me once that under different circumstances he would have had me reporting to a senior administrator. But the fact is this kind of communication between president and athletic director has become standard procedure among universities and is highly recommended by the NCAA. He didn’t want that. Now he does it with [Dooley’s successor, Athletic Director Damon] Evans and I am pleased that is the case.”

Adams’s tendency of not following traditions established by former presidents also showed up in other relationships. For more than fifty years it had been a tradition of Georgia presidents to join the Athens Rotary Club. Presidents O. C. Aderhold, Fred Davison, Henry King Stanford, and Chuck Knapp were all Rotarians. This association served them well in establishing good relationships in Athens. Adams wanted no part of any local civic group, and his critics allege that this attitude was a major reason for a less than friendly “Town-Gown” relationship that developed.

Dooley said it became clear early on that Adams would use his role as chair of the UGA Athletics Board to make his presence felt more than most presidents in intercollegiate athletics. Soon after Adams’s arrival, Dooley brought in two outside consultants to evaluate UGA’s athletics program and to make recommendations for improvements.

Eugene F. Corrigan, former athletic director at the University of Virginia and Notre Dame and retired commissioner of the ACC, and Chuck Neinas, Big Eight commissioner and former executive director of the College Football Association, spent two days on the Athens campus in January 1999 interviewing administrators and coaches. Their official report, written by Corrigan and addressed to Dooley, generally praised UGA’s athletic programs and facilities and particularly Dooley’s tenure as AD. The report noted that a good relationship and direct access between the athletic director and the president was critical to both parties. The report said:

“It has always seemed to me that one of the main jobs of the AD is to protect the interests of the university (and the president) from all the sources both within and attached to athletics which can bring discredit to the institution. It allows the president to spend his time running the university—while always being aware of what is going on in athletics.”

Writing privately to Dooley, Corrigan was more blunt. “In my conversations with Mike Adams I was struck with the fact that this guy from Pepperdine and Centre College seems to want to be involved more closely with football,” Corrigan wrote. “I was quite direct with him and suggested that it was best to leave football issues to his AD (who knows just about everything there is to know about the game). However, he seems to want his board to know that he has contact with the football coach. I hope he heard what I told him, and more important, that he heeds the warnings. Mike should only talk to [head football coach Jim] Donnan at your request, and they both need to know that.”

Corrigan offered his friend Dooley this advice: “Victory is wonderful, but hardly sustainable in a league as competitive as the SEC. Don’t stay too long, because it can eventually only take away from the incredible accomplishments which you have achieved at Georgia. They should name the place for you.”

Corrigan further noted that in his interview with Donnan, the football coach felt he was underpaid compared with other Southeastern Conference coaches. And not long after that assessment Donnan began agitating for a new multi-year contract.

Dooley had hired Donnan from Marshall University, a Division 1AA school in December 1995, a year and a half before Adams arrived. After a 5-6 season in Donnan’s first year, the Bulldogs bounced back in 1997 to post a 10-2 record, losing only to Tennessee and Auburn and beating arch rival Florida 37–17.

Suddenly Jim Donnan was a hot commodity in the coaching ranks. The University of North Carolina, where Donnan had coached for several years under Vince Dooley’s brother, Bill Dooley, came calling with a $1 million offer to coach the Tar Heels. So Dooley began working on a new contract for Donnan.

After negotiations with Donnan slowed, the impatient Adams did an end run around Dooley, the Athletic Board, and the Athletic Association lawyers who were negotiating the contract. Adams made an under-the-table verbal deal to pay Donnan roughly $250,000 should he be fired with three or more years left on his contract. The president specified that Dooley, the Athletic Board, and the Athletic Association’s attorneys King & Spalding must not know about the deal.

Donnan’s Bulldogs were 9-3 in 1998 and finished the season with a come-from-behind victory over Virginia. The team dropped to 8-4 in 1999 but came from behind to defeat Purdue in the Outback Bowl. It marked the first time since the 1981–83 seasons that Georgia had finished their season ranked among the top sixteen teams in the polls. However, Georgia lost its final regular season game to hated Georgia Tech.

When the Bulldogs finished the 2000 season with an 8-4 record and again lost the final regular season game to Georgia Tech, Adams let it be known he was unhappy. “Our special teams [stink],” he told reporters after the game. “We can’t tackle. We don’t stay in our lanes. We just don’t cover.”

Later that week Adams fired Donnan, implying that there were “off the field” problems with the football program without specifying what they were. Rumors swirled that some team members were into drugs. Donnan felt obliged to respond saying flatly, “We don’t have any drug problems on our team.”

(Donnan’s successor Mark Richt couldn’t say the same. In 2003 campus police were called to McWhorter Hall where they arrested five football players and one basketball player on charges of drug possession. In that case Adams, who had helped recruit Richt from Florida State University, saw fit to say nothing. Richt was winning even more football games than Donnan had and was 3-0 versus Georgia Tech.)

The dismissal of Donnan triggered the secret $250,000 buyout clause that Adams had been hiding from Dooley and the Athletic Association. In January 2001, Donnan’s agent, Richard Howell, wrote Adams demanding that the university honor the agreement and pay Donnan. After Adams refused to discuss a settlement and weeks passed, Howell also contacted the Athletic Association attorney, Ed Tolley of Athens, and told him about the secret agreement. Tolley went straight to Dooley’s office.

“Are you aware of this secret deal?” Tolley asked.

Not only was Dooley not aware of it, he could hardly believe what he was hearing.

After consulting with then-Chancellor Stephen Portch, Adams came to Dooley’s office to explain. Adams acknowledged his “mistake,” Dooley recalled. But he blamed Jim Nalley, a wealthy Atlanta car dealership owner and friend of Donnan’s, who was acting as a go-between in the negotiations. “Adams told me if he wasn’t trying to get a lot of money out of him he’d tell him what he thought of him,” Dooley said.

The question then became what to do next, since the agreement hadn’t yet been made public. Dooley set up a meeting. Attending the meeting were Dooley, his personal attorney Nick Chivilis, and Tolley and Floyd Newton of King & Spalding, who were representing the Athletic Association. Adams sent on his behalf Steve Shewmaker, executive director of the Office of Legal Affairs, the university’s top lawyer and a personal friend whom he had brought to Georgia from Kentucky.

Shewmaker stunned everyone by suggesting the Athletic Association, which is funded by public donations, simply absorb the $250,000 without bringing the matter to the Athletic Association board, thus avoiding public exposure. This proposal smacked to the others as a cover-up and they quickly rejected it. They opted to bring the matter to the board for approval.

Shewmaker later told Deloitte & Touche auditors he didn’t recall suggesting they keep the Donnan payment secret, but everyone else at the meeting remembered it that way.

On April 17, 2001, the Athletic Association executive committee met in the executive conference room at the Georgia Center for Continuing Education on the UGA campus. Adams, who chairs the Athletic Association Board, called the meeting to order and began the discussion of Donnan’s contract. Rather than acknowledge a mistake, however, Adams implied the secret agreement was a misunderstanding.

According to minutes, “Dr. Adams said a verbal statement he made while Coach Donnan’s contract negotiations were underway was taken as a commitment to extend the contract by six months should he be released from his duties before the expiration date of the contract.”

The executive committee approved the payment unanimously and the full board approved it a week later.

Before the firing, however, Dooley, perhaps out of empathy for a fellow coach, had wanted to give Donnan another year to turn the team around or at least give him an opportunity to find another job. Dooley had met privately with Donnan and told him that he was going to recommend one more year but warned that he was not sure of the president’s reaction to the recommendation.

As events unfolded, however, Adams then met with the Athletic Board members to get counseling. The board backed his decision to fire Donnan. Afterwards, Dooley, perhaps because of his many years as a football coach, felt obliged to make public his feelings that Donnan deserved another year to right the ship.

Some felt Dooley’s comments were inappropriate. “I was on the Athletic Board and I favored firing Donnan,” said Hank Huckaby, then a senior vice president. “When Vince came out and said he’d give him [Donnan] another year, I’d have fired him [Dooley] right then.”

Huckaby said Donnan was fired for multiple reasons including suspicion of a lack of team discipline and “going 7-4 every year.” Also, he said Donnan lacked good political skills.

Dooley said he felt it only fair to let it be known at the press conference that he had recommended another year with the decision ultimately resting with the president. “In good conscience, I had to tell the truth about what I had recommended, though, as I stated at the time, the president had the right to make the final decision.”

In his autobiography written with AJC sportswriter Tony Barnhart and in subsequent interviews for this book, Dooley expressed his disappointment at being forced to retire earlier than he wanted. Other long-term coaches and athletic directors, like Bobby Dodd at Georgia Tech, Bear Bryant at Alabama and Darrell Royal at Texas, all had a say in their retirement, he said. Dooley said Adams wanted to put his own people in every position regardless of how proficient an individual might be at his job.

In his second year as president, Adams told Dooley that unnamed “key people” were not happy with Dooley as athletic director. “He said, ‘You’ve done a good job here, Vince, but you never want to stay too long. And, you need to have something named after you,’” Dooley recalled in his autobiography. “My first thought was, now that’s a crafty way to make a change. Is he thinking that I would want to resign in order not to stay too long and to have something named after me? Is he hoping that I will comply and gracefully retire on my own?” Soon, Dooley said he started hearing rumors, especially from his wife, Barbara, that Adams wanted to replace him. Dooley said he dismissed the rumors. He should not have.

As the rumors grew more persistent, Dooley wrote Adams a letter on December 15, 2000, asking for a four-year extension of his contract. Three days later the two men had a follow-up discussion on a flight to Tallahassee, Florida, to interview Mark Richt for the head football coach’s job. Dooley said he offered a compromise of three more years as athletic director and two as a fundraising consultant after his retirement. It was an offer that Dooley didn’t really want, but he proposed it in the spirit of compromise to avoid a controversy. And while in Tallahassee, Dooley said, Richt asked him, in Adams’s presence, how long he expected to remain as athletic director. Dooley told him that he expected to remain for at least three years to help him get the program off to a good start. Adams said nothing at the time or on the return flight from Florida, Dooley said. However, on January 29, 2001, Adams responded with a “Dear Vince” letter expressing gratitude for Dooley’s hard work in the search that resulted in hiring Richt. “I am pleased that you and I were ‘in sync’ with each other during the screening and interview process,” Adams wrote. “Despite some media analysis to the contrary, I believe you and I were close to being ‘in sync’ with the decision made by the Athletic Board executive committee consensus to make a change in the leadership for the football program. In some ways, what we were probably talking about was timing and not the end result. This has been a trying time for all involved, and I look forward to beginning this new year with optimism and excitement for what lies ahead.”

Adams’s letter then got into the meat of the matter. “After much thought on the points you have raised in your letter regarding your future work here and on what direction I want to take on campus in the coming years, I have decided to offer you a contract of four years service, but I very much want to structure it so that you serve two years as Director of Athletics and two years as a Special Assistant to the President for Athletic Development,” Adams wrote. Adams said he had discussed the arrangement with some “key people” including some members of the Athletic Board. While there was a multiplicity of opinion, Adams said, “I believe it is fair to say that most of the key people with whom I consulted believe this is a fair arrangement for the University of Georgia and provides the proper and well-deserved recognition of the important role you have played here and will continue to play.”

Adams proposed that Dooley’s contract become effective July 1, 2001. He would serve as director of athletics until June 30, 2003, and then transition to the job of special assistant to the President for two additional years. Dooley’s compensation and benefits would remain the same.

“On a personal note, your usefulness and effectiveness in this contract extension will be enhanced if you feel like you are being treated fairly, and it is important to me that you indeed feel this way,” Adams wrote. “It is my sincere hope that this arrangement will give you the opportunity to conclude your service to the University on a well-deserved high note. I think the arrangement described here is consistent with the one that Georgia Tech reached with Homer Rice and is significantly more rewarding financially than that agreement.” Adams concluded by suggesting the two men get together to hash out any unresolved issues.

Dooley said Adams was flat wrong about the offer being more lucrative than Rice’s contract. He was concerned with the two-year offer as athletic director. He wrote to Adams on February 1, 2001, stating his rationale for wanting three years, especially citing his commitment to Coach Richt, which was made in Adams’s presence and with no rebuttal by the president at the time or afterwards. According to Dooley, they met February 6, 2001, and Adams offered to extend Dooley’s tenure as athletic director to two and a half years with one and a half years as Special Assistant. Dooley asked for three years. Adams said “no,” Dooley recalled.

“When I asked him why he gave me half of a year, Dr. Adams said it was not uncommon with faculty appointments,” Dooley said. “When I reminded him that this was not at all a common practice in athletics, he basically said, ‘Take it or leave it.’ I told him I was going to take it, but I also said, ‘I’m going to take the high road publicly but I’m going to tell you that I disagree with you and your decision. I don’t think you’re treating me fairly,’” Dooley recalled in his autobiography. Dooley later said that it was “vindictive Adams,” once again, using the half year to justify the commitment that he made to Richt that was not questioned by him. In other words, Adams was covering himself by extending Dooley’s contract a half year to cover the football season only and not the second half of the academic sports year. The following day, February 7, 2001, Adams wrote confirming their previous day’s agreement but couching it as a three-year deal at an annual salary of $313,425.

“Consistent with our conversation yesterday, I am pleased that we have reached an agreement for your contract renewal as Director of Athletics for three years, commencing January 1, 2001. This new contract insures [sic] service at the University through December 31, 2003,” Adams wrote. But Dooley’s contract didn’t expire until June 30, 2001, so the contract extension was really for two and a half years, not three as the letter suggested.

Dooley accepted the contract extension publicly with appreciation, but privately he was not happy. Adams had heard from some “key people” that the half-year part of the contract extension was coming across publicly as petty and vindictive, according to Dooley. But instead of going directly to Dooley, Adams addressed the issue in a Question & Answer interview with Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Tim Tucker. Asked if he would have a problem with extending Dooley’s contract by six months to complete the school year, Adams said he would not. Dooley said that Adams called him the next day to discuss the interview and told him that Tucker had asked him an interesting question about an additional six months on the contract and he told Tucker that he would not have a problem with it. Dooley said he reminded Adams how adamant he was about not granting the six months in the contract discussions. But he told Adams he would gladly accept the additional time to round out a full year, if offered, but he wasn’t going to ask. In June 2001, six months were added to the contract, which would then expire in June 2004. This didn’t settle the issue as far as Dooley was concerned. By that stage in his career Dooley had signed numerous contracts, each followed by an extension. He insists that he saw this one as no different. Adams, on the other hand, felt differently. Anxious to get his own man in that important position, Adams wasn’t about to negotiate another deal with Dooley. In early 2003, with eighteen months left on his contract, Dooley said he began thinking more about staying past his scheduled June 30, 2004, departure. He was in good health and was being encouraged by friends to stick around past his scheduled retirement. Dooley said that he wanted to finish the fundraising campaign that was off to a great start, and finish some projects that were in the initial planning stages with the stadium and the coliseum.

Adams and his top lieutenants felt Dooley was campaigning with prominent Georgians to pressure Adams for a new contract. “Adams gave Vince an extension and Vince accepted it,” said Georgia Senior Vice President Hank Huckaby, who was treasurer of the Athletic Board. “But then he began almost immediately to get people to pressure Mike to extend his contract. Vince might have been able to pull it off but he went public with it.”

Dooley said Huckaby is flat wrong.

“It’s true that about a year and a half into the new contract and not ‘almost immediately,’ as Huckaby indicated, and after the encouragement of several people, I began seeking the counsel of some longtime friends about staying on.” He went to Adams who told Dooley he would “think about it.” About a month went by and Dooley had not heard from Adams.

Dooley said Huckaby is mistaken or misinformed about his going public with the request for an extension. Dooley said that former Atlanta Journal-Constitution sports writer Mark Schlabach, an aggressive reporter, called him about a month after he had made his request to Adams that he had heard that Dooley had asked to stay on. Dooley said he knew from experience that it’s nearly impossible to keep such an issue out of news. Nevertheless Dooley said he was surprised when Schlabach called, and he asked him to hold the story for fear it would interfere with ongoing negotiations. Schlabach agreed but was understandably nervous about it, Dooley said. “Two more weeks went by without my hearing from Adams, and with rumors intensifying and the competition hearing rumors Schlabach, in good conscience, needed to run the story,” Dooley said. And although he explained the situation to Adams and Tom Landrum, Dooley said it was obvious they didn’t believe him. Schlabach told him that Landrum had called him to confirm Dooley’s story, which Schlabach did, Dooley said. Nevertheless Adams was unconvinced and felt the leak came from the athletics office, telling Dooley that it didn’t come from the president’s office. Dooley isn’t convinced.

“I know from experience that anyone he may have consulted with could have, even innocently, said things regarding the issue,” said Dooley. “That is the way rumors get started and the media picks up on it.”

By then, Adams had become convinced that many unfavorable stories about him had originated in the Athletics Department, Dooley said. And these prompted him to push Damon Evans, Dooley’s replacement as athletic director, to make a change in the communications director in athletics. Dooley said that Claude Felton, widely regarded as among the very best sports information directors in the country, was targeted by Adams to be one of the staff members that Evans would replace. “While Damon agreed to let go some other staff members that Adams didn’t like, he was smart enough not to let the best communications director in the business go,” Dooley said. “If he had, it would have haunted him the rest of his career.”

The press leak had obviously irritated Adams, but Dooley felt it was incidental. Dooley asked for a meeting with Adams after he had not heard from the president for over two months. He wanted to stem the public controversy that was stirring over his request for a contract extension. Dooley suggested a compromise in order to stifle the controversy. Adams responded that “we will stick with the original contract,” Dooley said, and handed him a copy of a press release scheduled to be sent out immediately announcing the search for a new athletic director to be brought in six months before Dooley’s scheduled retirement. When this was released Dooley still had almost a year and a half left on his contract. Dooley claims that “it was unprecedented and vindictive. Adams was pouring salt on the wound.”

While the controversy over Dooley’s contract was raging, the men’s basketball program was undergoing an NCAA investigation. The NCAA probe centered on basketball players who allegedly were given grades by assistant coach Jim Harrick Jr., without attending class and other violations. Harrick’s father, head basketball coach Jim Harrick, was forced to resign on March 23, 2003.

Adams had personally interceded to bring Harrick to Athens. The two men had become acquainted when Adams was a vice president and Harrick was head basketball coach at Pepperdine University. Harrick later moved to UCLA where he coached the Bruins to a national championship in 1995. But, he was fired the following year for cheating on his expense account and had moved on to Rhode Island, where he was also having success as head coach of the men’s basketball team when UGA went after him.

Harrick wasn’t Dooley’s choice to succeed Ron Jirsa as head basketball coach at UGA. “We didn’t have him on our short list,” recalled Dooley. “We didn’t even have him on our long list to consider because of his past transgressions. We didn’t know him; and he was beginning to get up in age.” Dooley said Adams called him and started talking up Harrick. “Adams said, ‘I knew him when I was at Pepperdine. He’s a good coach.’ I said, ‘I know he’s a good coach. That’s beside the point.’” But Adams insisted that Harrick be added to the list of finalists and it became clear to Dooley that Adams wanted to give him top priority. And after Dooley’s first choice, Delaware coach Mike Brey, cooled to the Georgia job, Dooley said he felt Harrick was the next best choice. In retrospect, Dooley said, it was apparent Brey had gotten “bad vibes” from Adams during his interview. He had been very interested in the job but decided to stay at Delaware, a program with a lesser classification and without the potential of Georgia. A few years later, Dooley said he visited Notre Dame and talked with Mike Brey who had then become Notre Dame’s head basketball coach. Dooley said Brey told him, off the cuff, “I could have worked for you, but I could not have worked for that president of yours.” Dooley said that he was somewhat stunned but later realized what had happened. Adams had shrewdly maneuvered the hiring of Harrick.

Dooley said that he became even more convinced of that after he received a copy of a letter that Adams had written to the father of a high school recruit on June 28, 2002, in which he took credit for hiring Harrick. “I think you know that I was instrumental in hiring Jim Harrick . . . I chair the Athletic Board, which recently approved a contract extension and a pay increase for him . . . Jim Harrick is a longtime friend and an excellent coach,” Adams wrote.

At that time Harrick’s team was doing well and Adams was quick to step out front and take responsibility for hiring him. That would not be the case a short while later.

Not long after his arrival in 2000, Harrick began recruiting talented but troubled athletes such as Tony Cole, a point guard who had left several colleges amid controversy. Cole was dismissed from UGA after female student accused him of sexual assault. After his dismissal from the team, Cole went on ESPN on February 27, 2003, with allegations that he received money and favors from the Harricks while at UGA and that he and two other basketball players were given “A’s” in a “Coaching Principles and Strategic of Basketball” course taught by Jim Harrick, Jr., an assistant basketball coach.

Dooley and Adams made a joint decision to withdraw the basketball team from Southeastern Conference and NCAA tournaments. In a 2003 Athens Magazine article Dooley said, “We’ve had bruises, black eyes and strong winds of criticism, but we’ve always landed on our feet because we had a solid foundation of integrity as a base value.”

The NCAA and the university both quickly began investigations. In April 2004 university officials—including Adams, Dooley, and Harrick—met with the infractions committee in Indianapolis. Harrick by this point had already been forced to resign and his relationship with Adams had soured. Dooley recalls Adams proudly opened the meeting with a ten-minute dialogue mostly about himself and his qualifications and his experience in intercollegiate athletics.

As they broke from the meeting, Adams walked past Harrick and made a light-hearted comment. Harrick was in no mood for levity. “You are the sorriest sack of shit I’ve ever known,” he told a red-faced Adams. “If Adams had said anything back to him there’s no telling what would have happened,” Dooley said, but Adams wisely got out of the way in a hurry.

At the height of the Harrick controversy Adams called a meeting with senior UGA staffers Steve Wrigley, Hank Huckaby, and Tom Landrum. “I’m there with Damon Evans [assistant athletic director] and [sports information director] Claude Felton,” Dooley recalled. “I guess everybody was looking to the president to set the tone of how this crisis was going to be handled. I was shocked and rather suspect others were as well, when Adams said, ‘I want to cut his balls out,’” Dooley recalled.

Dooley said he thought to himself, “What in the hell am I listening to? What kind of leadership is that? Instead of him laying out an overall plan to address the crisis, his primary and only concern, at the moment, was to annihilate Harrick. I wanted Harrick to go and he needed to go, but I wanted us to find the best way of addressing the crisis for all concerned, especially the university. Adams wanted to make it as bad as he could on his old friend.” The incident gave the school a black eye at a time it had been making progress in climbing the academic ladder.

After one staff meeting to consider how to handle the Harrick matter, Dooley said Adams pulled him aside and said, “We both have a stake in this situation. Your legacy and my national reputation.”

Typically, Adams’s concern was more for himself than the university, Dooley said.

Perhaps the most embarrassing aspect of the NCAA investigation to university officials was the release of a final examination in a course on basketball taught by Harrick Jr. The questions included: “How many points does a three-point goal account for in a game?” “How many halves in a basketball game?” The university, which regularly makes the list of top party schools and had been trying to shake its image as a “football university,” briefly became a punching bag for late-night TV hosts. “I don’t know who was more embarrassed,” quipped Tonight Show host Jay Leno, “the college president, the coach, or the six players who got it wrong.” “It makes us look silly,” Scott Weinberg, then chairman of the faculty’s University Council, complained to the Associated Press.

The NCAA investigation, Adams’s well-known role in hiring the renegade basketball coach, and the ongoing feud over Dooley’s contract extension all came together. It looked as though Adams would be sucked into the vortex of a perfect storm, so widespread was the discontent both on and off campus. But to the media it looked like a sports story.

As tensions mounted, Atlanta Journal-Constitution sports columnist Mark Bradley weighed the situation. In a March 27, 2003, column Bradley determined that Adams, not Dooley, was on the hot seat and wondered if the president could survive.

“In his private moments,” Bradley wrote, “Vince Dooley must delight in the knowledge that he, the old football coach, has outflanked university president Michael Adams, the old political operative. With the Georgia athletics department trying to ride out the tempest wrought by Tony Cole, the athletic director himself has managed to dance between raindrops. His rival, meanwhile, has gotten drenched . . .”

“Such a thing could happen again,” Bradley continued. “Adams tried to run Dooley off two years ago, haggling over months in a contract extension, but this athletic director may remain long after the president is gone. Adams has come off looking scared and silly . . . Dooley, on the other hand, has seemed serious and statesmanlike.”

Bradley misread the situation.

Unlike former President Davison, forced out in the Jan Kemp controversy, Adams lined up powerful backers including Governor Sonny Perdue, Chancellor Tom Meredith, and a majority on the Board of Regents, including Don Leebern (who would be reappointed by Perdue to a third term after Leebern made a $200,000 contribution to the Georgia Republican Party).

When Adams subsequently denied Dooley’s request for a contract decision in June 2003, it stirred a firestorm. Many Georgia alumni and boosters were critical of Adams’s treatment of Dooley, but many influential insiders saw the Dooley contretemps as simply another opportunity to express their profound displeasure with Adams’s leadership and spending habits.

Seeing that the Harrick controversy was hurting the university, Dooley issued a statement asking the people of Georgia not to associate his name with issues that they may have with Adams’s leadership. Adams seized the olive branch saying he would seek Dooley’s advice, which Dooley said he did.

“He asked me what would make me happy,” Dooley said. “I gave him my advice, not for me, but what I thought was best for the university. If you will give me just one more year then I think that most Georgia people will be very pleased with that and that you have extended an olive branch. And all it is, is just one more year, and I would be very happy with that and I think that many Georgia people would be. And it would help toward the healing.”

Adams said he would think about it but later turned down Dooley’s offer, apparently confident he had the power base to refuse the compromise. In his memoir, Dooley speculates that Adams used the time to line up support from “key people” not to grant a contract extension. Dooley said Adams frequently referred to unnamed “key people” during their contract discussions. As events have subsequently shown, Adams’s “key people” certainly included Governor Sonny Perdue and Dooley’s old friend, Regent Don Leebern.

Truth be told, Adams already had Perdue in his pocket by the time Dooley proposed his compromise. Dooley’s contract extension wasn’t denied by Adams until June 2003, but Perdue had already declared his support for Adams on March 12, 2003, two days after the president suspended Harrick.

Many of Dooley’s close supporters, including his wife Barbara, believe that Adams conspired with Perdue and Leebern to end Dooley’s career. Barbara Dooley didn’t approve of Leebern’s abandonment of his wife and she let Leebern and Yoculan know it. She is convinced that this and Vince Dooley’s refusal to name Yoculan as deputy athletic director did in her husband.

Vince Dooley doesn’t share his wife’s view of the split with Leebern. After his contract was not renewed, he wrote a somewhat cryptic letter to the editor which he sent to several newspapers saying so, and forwarded a copy to Leebern with a “heads up” note:

There have been a number of articles, editorials, and letters in recent in recent weeks regarding our gymnastics program and some have mentioned my relationship with Don Leebern.

It is true that Don Leebern and I have been longtime friends since I arrived at Georgia over 40 years ago. It is natural that during a friendship over a long period of time, people will not always agree on various issues and thus we have not been as close as we once were.

However, the assumption that the current situation was caused by Leebern’s support of President Adams in his decision not to honor my contract extension request is absolutely false from my perspective. In fact, if I had been a Regent at the time, I would have supported President Adams’s decision (despite privately not agreeing with that decision). The president has a right to make those personnel decisions and therefore I would expect all the Regents to support that decision—which they did—including several friends of mine.

Dooley consistently laid blame for his departure squarely on Adams, who had gained the power broker support that he needed. “He obviously wanted to make a change early on and waited for the right opportunity to make the move,” Dooley said.

Regardless, it was the president’s prerogative to make that decision, Dooley said. When the chance came, Dooley said he felt that Adams was not forthright. “He was constantly posturing, drawing from his political background. Had he been straightforward with me, more than likely, this situation would not have caused such an unfortunate controversy for the university.”

The issue was not whether Adams had the authority to remove an athletic director; that was a university president’s call. But as we have seen, the events leading up to Adams’s decision had already left a bitter taste in the mouths of Dooley and his close supporters, and the infighting was about to get much worse.

An opinion poll commissioned by the Atlanta-based Insider Advantage internet newsletter in May 2003 found that 64 percent of Georgians held a favorable opinion of Dooley while only 18 percent felt the same way about Adams. Nevertheless, on June 10, 2003, four days after Adams shut the door on Dooley’s career at UGA, the Regents met to formally respond to the developing schism. At the beginning of the Regents meeting, chairman Joe Frank Harris, a former Georgia governor, read a statement.

Please allow me to take a moment of personal privilege as your Chair to comment on a current issue that has generated a great deal of attention. I’m speaking of the publicity surrounding the University of Georgia and its athletic program.

First, let me recognize the extraordinary contribution of Vince Dooley to the University of Georgia in a career spanning four decades. He has established a legacy envied by athletic programs across the country. We deeply appreciate all Mr. Dooley has done and will continue to do for UGA and the state of Georgia.

In February 2001, President Michael Adams and Mr. Dooley both agreed on the term of service of Mr. Dooley as UGA’s athletic director. The president has decided to honor the agreement and the Board of Regents unanimously supports the president’s commitment. Let me just add another personal comment. Chancellor, members of the Board, I want to take this moment and personally salute President Adams for his leadership at UGA. We point with great pride to the progressive and positive positions President Adams has taken to move UGA to new academic heights. We are proud of Michael Adams and of the record he has established. He has our unanimous support. The statement stands on its own. President Adams is here today. We just want you to know we appreciate the leadership you are providing and you have this Board’s unanimous support.