Читать книгу Behind the Hedges - Rich Whitt - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 Legacy

ОглавлениеChartered two years before the founding fathers gathered in Philadelphia to adopt the U.S. Constitution, the University of Georgia was the first college in America to be created by a state government. The concepts underpinning its charter—which established the school as the head of the state’s educational system—laid the foundation for public higher education in America. In 1784, at the urging of Governor Lyman Hall, the state set aside forty thousand acres to endow a university. The following year, Abraham Baldwin introduced legislation that passed in the General Assembly creating the university’s charter. Baldwin then served as the first president of the University of Georgia, during its planning phase from 1786 until it opened to students in 1801. (By then, North Carolina had followed Georgia’s lead and moved to a faster track in establishing a state-supported institution of higher learning, the University of North Carolina, which opened in 1795.)

Governor Hall and President Baldwin were both Yale-educated Connecticut Yankees; the architecture of their new campus in Athens was modeled on that of Yale, and the bulldog is the mascot for both schools. Baldwin and Hall shared a vision of the importance of education to a developing state and nation. Baldwin once said that Georgia must place its youth “under the forming hand of Society, that by instruction they may be moulded to the love of Virtue and good Order.” Two centuries later, it would be hard to overstate the importance of the University of Georgia to the people of the Peach State. The school motto, “To teach, to serve and to inquire into the nature of things,” spells out its broad mission. The oldest, largest, and most comprehensive educational institution in the state, the university’s first mission is to educate Georgia’s people. But it is also charged with improving the quality of life of all Georgians and discovering new knowledge through research. Though it has neither medical nor engineering schools, it has in most respects fulfilled that mission admirably.

The university has also carved its legacy deeply into Georgia’s political landscape. Alliances formed in its law and business schools have often been tempered and honed in the arenas of state government. Since 1851, UGA has educated twenty-five governors and countless state and local politicians. Luminaries of every political persuasion have advanced through the famous arches at Athens. Georgia’s current Republican governor, Sonny Perdue, and both of Georgia’s U.S. senators, Saxby Chambliss of Moultrie and Johnny Isakson of Marietta, are UGA graduates. Perdue, who hails from the town of Bonaire in central Georgia, is the fifth consecutive governor and seventh of the last nine to hold a degree from the University of Georgia. Other prominent graduates include Dan Amos, CEO of AFLAC; Robert Benham, the first African American chief justice of the Georgia Supreme Court; Robert D. McTeer, former CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank in Dallas; Charles S. Sanford Jr., former chairman/CEO of Banker’s Trust Company; Pete Correll Jr., retired CEO of Georgia-Pacific Corporation; retired Synovus CEO James Blanchard; Billy Payne, chairman of the Augusta National Golf Club; and the late humorist Lewis Grizzard, to name just a handful.

Yet Georgia was never an institution for the elite only. In its first two centuries—with one big exception—the university’s doors were open to just about anyone who could afford the modest tuition and board. Generations of Georgians from small towns and large cities alike followed one another to Athens, creating an interwoven tribe of alumni whose devotion to their alma mater almost needed to be experienced to be fully understood. It’s not uncommon today to hear a Georgian boast of being the third- or fourth-generation Georgia Bulldog in his or her family. This loyalty was partly by design: until 2002, so-called “legacy” admissions gave preferential treatment to applicants whose immediate family members had attended UGA. This policy no doubt contributed to the historical discrimination against blacks—the exception to the open admission philosophy noted above—and ended only after the school’s affirmative action program for African American students was struck down by the courts in 2001.

Like most Southern institutions, the University of Georgia struggled with the race issue. Although the original charter pledged that no citizen could be denied enrollment at the university because of religious affiliation, sex, or race, slaves were never considered citizens, even after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. And even after the end of the Civil War, African Americans were barred from the University of Georgia for another hundred years.

Race, of course, has been at the heart of some of Georgia’s greatest trials and triumphs. It boiled to the surface in 1941 when a University of Georgia secretary gave a sworn statement that the dean of the School of Education favored racial integration. Governor Eugene Talmadge, an avowed segregationist, demanded that the Board of Regents fire Dean Walter Cocking. To appease the governor, the Regents voted 8–4 to dismiss Cocking. However, the Regents reconsidered after President Harmon Caldwell threatened to resign in protest. At a special executive session two weeks later, the Regents reversed themselves and voted 8–7 to retain Cocking. The Regents’ action infuriated Talmadge, who snapped his galluses and demanded the resignations of three of his own appointees so he could pack the board with more subservient members. The three Regents refused to resign but two other members did quit and the Board was reconstituted more to the governor’s liking. The Regents then voted 10–5 to fire Cocking and also dismissed Marvin Pittman, the president of Georgia State Teachers College (now Georgia Southern University).

Both the Georgia university system and Talmadge would pay dearly. The Southern Association of Colleges and Universities met later that year and voted unanimously to strip most of Georgia’s public colleges of their accreditation. That stern action helped turn Georgia voters against the race-baiting Talmadge and his meddling in higher education. In 1942, voters instead elected as governor a progressive young legislator, Ellis Arnall, who promised to remove the university system from political interference.

Arnall—a Georgia law graduate—kept his promise. One of Governor Arnall’s first acts was to sign legislation creating a constitutionally independent Board of Regents, thus ending overt political interference in Georgia’s higher education system (although Georgia governors still appoint Regents and have retained considerable influence over the board).

The struggle to desegregate the University of Georgia began in earnest in 1950 when LaGrange native Horace Ward applied to attend law school. Ward had earned an undergraduate degree from Morehouse College and a master’s degree in political science from Atlanta University.

The Regents weren’t as supportive of a young black man as they had been of Dean Cocking. Responding to Ward’s application, the University System Board of Regents established new criteria for admission, including personal recommendations from UGA alumni. Ward sued, but (in one of the many ironies of the segregated South) before the case could be heard, he was called on to serve the country that considered him a second-class citizen. When Ward returned from military service, he renewed his lawsuit and the case was finally set for trial in December 1956. The judge then dismissed the case as moot because Ward had meanwhile enrolled at Northwestern University’s law school.

Ward was not finished with the University of Georgia, though. After graduating from Northwestern, he returned to Atlanta and soon joined famed civil rights attorney Donald Hollowell in representing Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes, who had applied for admission to UGA in 1959 after graduating from the segregated Turner High School in Atlanta. Both were honor students, but university officials threw up roadblocks, claiming, among other excuses, that the dorms were full.

On January 6, 1961, U.S. District Judge William A. Bootle ruled that the pair were fully qualified to enter the university and “would already have been admitted had it not been for their race and color.” Three days later, on January 9, Hunter and Holmes were escorted to class as a crowd of white students chanted, “Two-four-six-eight. We don’t want to integrate.” There were no further demonstrations until January 11, when a student mob descended on Hunter’s dormitory after a basketball game between Georgia and Georgia Tech (Georgia lost in overtime, 89–80). Sports reporter Jim Minter, later to become editor of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, was on campus covering the game. Years later he wrote about the evening in a newspaper column: “I walked out of the gymnasium into rioting. Rocks were thrown, torches burned, threats shouted. The dean of students was hit in the head by a brick.” Minter recalled that eighteen students left the university following the incident; some were expelled, others just refused to attend school with blacks.

Holmes and Hunter were escorted back to Atlanta by state troopers. Dean of Students J. A. Williams told them he was suspending them “in the interest of your personal safety and the welfare of more than seven thousand other students at the University of Georgia.” More than four hundred faculty members signed a petition protesting the removal of Hunter and Holmes and calling for their return. A few days later, the pair did return, under the protection of a court order. Still, there was talk of closing the university. In 1956, the Georgia legislature had passed a resolution that forbade integration of schools and threatened the funding of any schools that did desegregate. However, Governor Ernest Vandiver, himself a Georgia graduate, kept the university from closing.

Hunter and Holmes graduated in 1963 (both had already gained some college credits elsewhere while their lawsuit was pending). Holmes had earned cum laude distinction and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. He went on to receive a medical degree from Emory University and became an orthopedic surgeon in Atlanta. Hunter-Gault became a distinguished journalist, first in newspapers and later with PBS and CNN, winning two Emmys and two Peabodys. In 1988, she returned to the University of Georgia as the school’s first black commencement speaker. Horace Ward was later appointed a U.S. district judge and presided over the 1986 Jan Kemp lawsuit (see Chapter 6). The University gave Donald Hollowell an honorary degree in 2002 in recognition of his legal battles on behalf of Hamilton and Hunter-Gault.

The generations of white Georgia alumni may have gotten over their resentment of integration more easily than they have accepted the loss of legacy admission entitlement for their children and grandchildren. The roots of this particular change can be traced to the 1990 gubernatorial campaign. Long-time Lieutenant Governor Zell Miller was seeking the Democratic Party’s nomination for governor against four other candidates. Lottery fever was sweeping the nation but few Southern states had taken the plunge into state-sanctioned gambling. Many state politicians felt Georgia voters were too conservative and too “Baptist” to approve a lottery. But Miller was watching the caravans of Georgians streaming into Florida every week to play the numbers. Where other candidates saw danger, Miller saw opportunity.

An astute observer of all human condition except his own, Miller had been Georgia’s lieutenant governor for sixteen years. His habit of taking multiple positions on every major issue had earned him the nickname “Zig-Zag Zell.” Miller was not the favorite in a primary field that included Andrew Young and State Senator Roy Barnes. Young was popular and a civil rights legend, former aide to Martin Luther King, Jr., former congressman, former ambassador, and two-term former mayor of Atlanta. Barnes, considered a rising star in the Democratic Party, had the strong backing of the politically powerful Georgia House Speaker Tom Murphy, an arch-enemy of the lottery and Zell Miller.

Miller had cut his teeth in the executive branch as the chief of staff for segregationist Governor Lester Maddox, he of ax-handle and backwards-bicycle-riding fame. After the Georgia House of Representatives bottled up legislation to put the lottery issue on the ballot in 1990, Miller vowed to make it the central issue of his campaign. Miller had seen politically unknown Kentucky businessman Wallace Wilkinson ride the lottery issue into the governor’s office in that state three years earlier. Wilkinson’s campaign manager, James Carville, the “Ragin’ Cajun” who would head Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, signed on as Miller’s campaign manager.

Miller won 41 percent of the vote in the five-man primary and defeated Young in the runoff. Young had also supported a lottery but Miller had established himself as the lottery candidate. Miller then defeated the Republican nominee, State Senator Johnny Isakson, by 100,000 votes in the November general election.

Miller’s election was seen as a mandate to create a state lottery for education and he quickly drove a proposed constitutional amendment through the General Assembly. Georgia voters approved it in 1992. The lottery proceeds were earmarked for pre-kindergarten, technology, and, most importantly, the HOPE Scholarship Program which pays the full tuition for any Georgia high school student who graduates with at least a “B” average in a core curriculum. Since its inception in 1993, the HOPE scholarships have paid more than $4 billion to students in tuition, books, and fees.

Many of Georgia’s best and brightest students who once routinely left the state to attend other acclaimed universities are now staying home to take advantage of free tuition. Nearly 80 percent of the freshmen who enrolled at the University of Georgia in the fall of 2007 were from Georgia and 99 percent had received HOPE scholarships; they also had an average SAT score of 1233.

This rising tide of high-scoring students had unintended consequences for some of Georgia’s most loyal alumni. Many among the generations of Georgians who have followed one another to Athens over recent decades have done so using so-called “legacy” points awarded to the sons and daughters of Georgia alumni. In some cases, those points meant the difference between admission and rejection.

Former Governor Roy Barnes, himself a UGA graduate, acknowledged that many Georgians view attending the state’s flagship university as a birthright. And when their sons and daughters began being turned away, it ruffled feathers. “Some of these folks on the [University of Georgia] Foundation have been big givers,” Barnes said. “Now a lot of their children can’t get in the university and they blame [school officials]. I hear that all the time: ‘I’ve been giving to the university and four generations have gone there and now my kid can’t get in.’”

The University of Georgia is a top-tier state university. Its sixteen schools and colleges offer twenty-two baccalaureate degrees in 140 fields, thirty master’s degrees in 124 fields, and four doctoral degrees in 87 fields. And Georgia is a financial bargain. U.S. News and World Report has ranked UGA as high as seventh among public universities on its “Great Schools, Great Prices” list, which relates a school’s academic quality to the cost of attending. Kiplinger’s magazine has ranked UGA tenth on its list of best values among public colleges and universities based on academic quality, cost, and financial aid. The Princeton Review’s “Best Academic Bang for Your Buck” has ranked UGA ninth among 345 public and private colleges. And because nearly all in-state first-year students come to Georgia on the HOPE scholarship, the university has been ranked by Money magazine as one of nine “unbeatable deals” nationwide where students can attend college tuition-free.

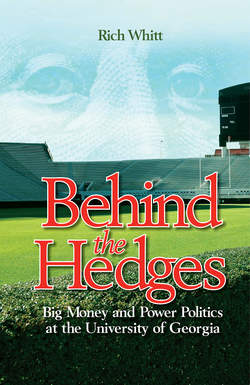

Princeton Review, by the way, has also ranked the university twelfth among the nation’s best party schools, but if parties and academics aren’t enough, Georgia has one of the most storied athletic programs in the country. The university fields competitive NCAA teams in basketball, track, swimming, gymnastics, baseball, and other sports, though football dominates. On a typical Saturday afternoon each fall more than ninety thousand crazed red-and-black-clad loyalists pour into Sanford Stadium to watch their Dawgs do battle, as they say, “between the hedges.” Thousands more tailgate outside the stadium or tune into the radio broadcasts where for decades they listened to the legendary voice of the Bulldogs, Larry Munson. Georgia played its first football game in 1892, beating Mercer University 50–0. A month later UGA and Alabama Polytechnic Institute, better known today as Auburn University, met for the first time in what has become the Deep South’s oldest football rivalry. UGA won that game 10–0. In 115 seasons, the Bulldogs have an overall record of 713–381 with 34 ties. The football team has won five national championships, and 1982 Heisman Trophy winner Herschel Walker no doubt could have gotten even the votes of geriatric woolhat segregationists if he had announced for governor after leading the Bulldogs to a 32-3 record in his three varsity years.

And Georgia has continued to move forward even in the midst of the controversy of the past few years which is the focus of this book. A new $42.2 million Student Learning Center opened in the heart of campus in 2003. It is considered one of the largest and most technologically advanced such facilities at an American university. The 206,000-square-foot building contains twenty-six classrooms and ninety-six small study rooms. An electronic library allows users to access materials in other university libraries. The building has five hundred public-access computers, and many classrooms and study rooms have wireless internet access. There is also a coffee shop and reading room.

A new medical school, to be jointly operated by and staffed with professors from UGA and the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta, is scheduled to open in 2009. The 200,000-square-foot Paul D. Coverdell Center for Biomedical and Health Sciences opened in 2006, providing space for faculty research in biomedicine, ecology and environmental sciences.

The University of Georgia today is big in every respect. Big in academics, with 32,000-plus students who boast rising test scores. Big in sports, with high-achieving athletes in almost every category and with distinguished alumni at all levels of professional and international competition. Big in business, with graduates in the executive suites of major corporations. Big in the professions, with its law graduates heading top firms and filling key judgeships. Big in politics, as previously noted. Big in philanthropy, with supporters giving the university about $100 million a year and with its endowment now approximately half a billion dollars. And big as a business itself, with an annual budget of $1.3 million.

When an institution is that big, and when it has a reputation built up over two centuries and carries with it the hopes and aspirations of an entire state, the person who heads up that institution becomes both its symbol and its lightning rod. The “forming hand of Society” and “the love of Virtue and good Order” come into play, as Lyman Hall and Abraham Baldwin might have put it.

Hall and Baldwin might have had quite a lot more to say if they could have been around in 1997 to see how Dr. Michael Adams was selected to be the next president of the University of Georgia, and to watch what unfolded over the next few years.