Читать книгу Zen Masters Of China - Richard Bryan McDaniel - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue in India

The story goes that one day the Buddha’s disciples were gathered at the Bamboo Grove to listen to one of his dharma talks. Dharma is a word with several meanings. At times it simply means “phenomenon” or the way things are, the laws governing existence. When used in Buddhist texts, however, it usually refers to the general content of the Buddha’s teachings.

Among the disciples gathered that day was one named Kasyapa. To distinguish him from another disciple with the same name, he came to be known as Mahakasyapa or the “Great Kasyapa.” Mahakasyapa was the son of the richest man in the kingdom of Magadha, located in what is now the northeastern corner of India. His father’s wealth was so great that it exceeded that of the king. But wealth alone does not necessarily bring contentment or security.

Mahakasyapa was drawn to religious life after waking one morning to find a poisonous snake creeping along the bed beside his wife. Mahakasyapa froze in terror, unable to brush the serpent away for fear that if he startled it, it would bite his wife and cause her death. When at last the snake moved off the bed, onto the floor, and out of the bedchamber, Mahakasyapa woke his wife and told her of the danger in which they had been. The two of them were sensitive and reflective individuals, and the incident made them ponder the fragile nature of human life. It became clear to Mahakasyapa that he should look for a teacher who would help him understand the significance of life. So he sought out the Buddha, who accepted him as a pupil.

Those who gathered about the Buddha were referred to as the sangha. They lived collectively, following a strict discipline that included the practice of dhyana, or meditation. Kasyapa adapted to sangha life easily.

On the day in question, the disciples who gathered to listen to the Buddha probably expected him to discuss one of the many themes he returned to time and again—such as the origin of suffering and the path to freedom from suffering, or the chain of causation, or the doctrine of impermanence. However, on this occasion, instead of speaking the Buddha simply sat before the assembled monks and twirled a flower between his fingers. Some disciples shifted in their seats uneasily, some felt impatient, others wondered if there were some hidden significance in the Buddha’s silence; but Mahakasyapa smiled—even though, it is said, he attempted to control his expression because it was, after all, a solemn occasion.

The Buddha noticed that smile and finally spoke: “I have the eye of the true teaching,” he told the assembly, “the heart of nirvana—or liberation—the true aspect of no-form, the unquestionable dharma. Today I have passed these on to Mahakasyapa.”

Buddha is not a name but rather a title meaning “the awakened one.” The man now known as the Buddha had been a prince named Siddhartha Gautama. At his birth, astrologers predicted that he would either grow up to become a great secular or great religious leader. His father, King Suddhodana, naturally hoped the boy would succeed him on the throne, so he tried to shield his son from those sorrows that often draw people to the religious life.

The child was raised in luxury and seclusion. The accounts of his early life insist that he had no contact with sickness, old age, or death until he was nearly thirty years old, by which time he was already married and his wife was pregnant.

However, the ease and privileges of his life had eventually begun to pall, and he grew curious about what life was like beyond the grounds of the palace. So one day he ordered his charioteer, Channa, to take him to see the kingdom he was to inherit. On that first outing, they encountered an old man. The prince stared at him in wonder, then turned to Channa and asked:

“Tell me, Channa, what kind of being is that over there, moving so slowly and with such great effort? Can it be a man? He does not look like other men I have seen. His hair is sparse and white, unlike that of other men. His skin is wrinkled and hangs loosely on his neck and arms, unlike that of other men. His mouth is sunken, and he appears to lack the teeth of other men. His back is stooped, and he supports himself on that stick, unlike other men. His movements are halting, and his limbs quiver, unlike those of other men. What kind of being, O Channa, is he?”

“Prince, he is only a man like yourself who has grown old and frail with the passing of the years.”

“Is it perhaps, Channa, that only this man is subject to this deterioration of age, or are all men so subject?”

“All men, my Prince, are subject to the deterioration of their powers and faculties as they grow older. Even you, sir.”

Distressed by this information, Prince Siddhartha ordered Channa to return to the palace. But not long after, he felt compelled to go out into the kingdom once again. On this occasion, they encountered a man sick with fever, emaciated but with a swollen belly, covered with flies, and soiled by his own filth.

“What kind of being, O Channa,” Prince Siddhartha asked the charioteer, “is that over there? Surely his body is not like that of other men. His shaking and sweating are not like the behavior of other men. The moans and incomprehensible sounds proceeding from his mouth are not like the words other men speak. What kind of being is he?”

“Prince, he is only an unfortunate man, such as yourself, who has fallen ill with a fever.”

“Is it perhaps, Channa, that only this man is subject to the ravages of illness, or are all men so subject?”

“All men, my Prince, are subject to the ravages of illness. Even you, sir.”

“Then how can humankind bear this burden, knowing this to be their fate? If physical beauty and good health are so fragile and fleeting, how can one take any joy in entertainments and the pleasures of the senses?” And once again, he ordered Channa to return to the palace.

For a time, the prince tried to lose himself in the pleasures and privileges of his station, but eventually he once more felt compelled to venture out of the palace grounds. On this occasion, they came upon a funeral procession.

“Why, O Channa,” Siddhartha asked, “are these people wailing and lamenting so? And what kind of being is that which they carry on that litter? He does not move as other men do. The odor that comes from him is not like that of other men. Even the mottled color of his skin is not like that of other men.”

“Prince, that is a corpse. The man has died. The breath has left his body, and he will never again be with his family and friends to share their joys and sorrows. The ones who carry him are those same friends and family, mourning him as they take his body to be burnt.”

“And is it perhaps, Channa, that only this man is subject to death, or are all men so subject?”

“All men, my prince, are inevitably subject to death. Even you, sir.”

Siddhartha returned to the palace, but by now had lost all interest in the distractions his father provided. He was so devastated by what he had discovered that he was unable to rest. And so, for a final time, he ordered his charioteer to take him from the security of the palace to the world beyond. On this occasion they came upon a figure with a shaved head, walking with serenity and dignity. He wore a robe that left one shoulder bare, and he carried a begging bowl. He went up to the door of a house, knocked, and waited calmly until the housewife looked out at him. Wordlessly, he bowed and proffered the empty bowl, into which she placed a small ball of rice.

“Tell me, O Channa, what kind of being is that over yonder? He has a serenity and dignity I have not seen in other men.”

“He is a bhikku, my Prince, a monk. He is one who has left his home and given up all of his possessions. He has learned to control his passions and his ego. He spends his time in meditation and devotional activities seeking to learn the secrets of Being.”

When he heard these words, Siddhartha felt as if a door had opened. He sensed for the first time the purpose of his life and the destiny for which he had come into the world. So it was that he gave up his royal position to become a wandering monk. In doing so, he sought to understand the purpose of his existence and to find a way to escape the bondage of a life subject to illness, age, and final dissolution.

In that culture, it was commonly believed such concerns could best be resolved not by reasoning but through the practice of meditation. Accordingly, Gautama studied with two of the most celebrated meditation masters of his time, but he was dissatisfied with what they were able to teach him. Leaving them, he went on to practice severe austerities with a group of ascetics for six years. These practices also failed to help him achieve what he was seeking and brought him to the brink of starvation. He had become so weak from this lifestyle that one day he collapsed. A young girl, sent to take a food offering to the spirits of the forest, found him and offered him a bowl of milk. He accepted her gift and from that moment gave up the practice of asceticism. His former companions considered this a betrayal of their way of life and abandoned him.

Left on his own, he retired to a grove of fig trees, where he sat under a tree that would later be known as the Bodhi Tree, or Tree of Enlightenment. There he vowed he would remain meditating until he came to full and complete enlightenment.

Even after years of practice with meditation teachers and further years of ascetic activity, the future Buddha still did not have complete control over his thoughts and emotions. As he sat beneath the tree, he was assailed by sexual images, anxieties, and fantasies of accomplishment. But not allowing these to distract him, he remained focused, seeking an answer to the questions of life and death, of existence and human experience.

He sat through the night, focused on these questions, and ignoring the random distractions that arose in his mind. Then as dawn broke he saw the planet Venus on the horizon, and at that moment he became awakened—he came to full and complete enlightenment. Tradition has it that at the moment of his enlightenment, he exclaimed: “O wonder of wonders! All beings just as they are are whole and complete! All beings are endowed with Buddha-nature!” All beings, in other words, have the inherent capacity to realize that their most basic nature, their fundamental nature, is no different from that of all existence.

This was a well-known experience in the traditions current in Buddha’s time. It was experience of what in Sanskrit was called advaya, which can be translated as “nonduality.” While most people have a sense of themselves as an entity within the world confronting other entities through their six senses (the Asian tradition considers thought a sixth sense), in the experience of advaya there is no sense of self separate from all else. For this reason, the experience came to be called, in Buddhism, sunyata or “emptiness.”

The newly awakened Buddha remained beneath the Bodhi Tree for forty-nine days after his enlightenment, during which time he contemplated his experience and reflected on the laws of causality to which humankind is subject. On the forty-ninth day, the Buddha reflected that, although he had found the Path of Liberation he had sought so diligently, he was uncertain whether he would be able to communicate what he had discovered to others. The next morning, as he went to the river to bathe, he paused to observe the lotus flowers growing there. The flowers were at different stages of development. Some were little more than roots buried in the mud; others had stems that still had not risen to the surface of the water; still others had emerged but their leaves remained curled shut; the buds of yet others were just opening; and finally there were flowers in full bloom. In like manner, he reflected, people were at various stages of development, but in each person there existed the seed of enlightenment—their inherent Buddha-nature. With proper cultivation, all persons are capable of realization and enlightenment. So the Buddha decided to share the dharma (the teaching) with others.

Spiritual teachers were common in that era. The Buddha became one teacher among many. He was known by many names. One of his most common titles was Shakyamuni, or “sage of the Shakya clan.” The clarity and simplicity of what he taught quickly attracted followers, and, within a short time, he had a large following. Because the Buddha was recognized as an enlightened being, many people came to him hoping he would be able to help them with their problems. While a few may have wanted to achieve their own awakening, most considered that beyond their capacities and simply sought the assistance of one who had attained that height. They brought to him the type of concerns that humankind has always turned to religion to address. They wanted explanations for why things were the way they were. Others sought guidance on how they should live their lives. Some, no doubt, were looking for that companionship which is found in being a member of a community with shared beliefs. And, of course, there were those who wanted magic, who came in hopes of miracles.

He responded to those questions that came from the heart, which needed to be answered if the individual were to attain peace, but he ignored questions that were purely theoretical—such as those posed by the monk Malunkyaputta, who asked whether the world was eternal or finite, whether the soul and body were one or separate, whether or not there was an existence after death, and so on. To be concerned about such things, the Buddha told Malunkyaputta, was to be like a man wounded by an arrow who refused to have the arrow withdrawn until he knew who had crafted it, what type of wood was used, or what feathers were used in the fletching. Malunkyaputta’s questions were about issues that do not matter and are probably unanswerable, so the Buddha refused to offer an opinion on them.

But to those who sought answers to basic questions such as why there was so much suffering in the world, the Buddha provided teachings such as the Four Noble Truths, which explain that suffering is inherent in the human condition because of desire and that only by letting go of desire can one overcome suffering. To those seeking guidance about how they should live their lives, he offered the Eightfold Path, the last two steps of which are “correct mindfulness” and “correct meditation.” And to those seeking miracles—such as the woman Kisagotami whose infant son had died from a snakebite—he responded with compassion and kindness. In Kisagotami’s case he told her that if she could find a household that would give her a single mustard seed, he would cure her child; but, he added, the household must be one wherein no one had ever died. Through this gentle method, he led her to recognize the reality of suffering, the Four Noble Truths, and the Eightfold Path.

The wisdom the Buddha demonstrated in his teachings was the result of his enlightenment, but the achievement of that wisdom was not the content of his enlightenment. He was not enlightened because he understood the laws of causation or realized the formula of the Four Noble Truths. The enlightenment experience, which led him to understand these things, was beyond verbal formulae and logical structures; it could not be expressed in words. The Buddha’s insights, which were the result of his enlightenment, were recorded—and no doubt elaborated upon by others—in the scriptures called sutras. What the Buddha transmitted to Mahakasyapa was not dependent upon words and letters but something outside the scriptures. What he transmitted to Mahakasyapa was the experience of awakening itself. Mahakasyapa’s realization was the same as the Buddha’s. And when the Buddha recognized Mahakasyapa’s awakening, it was not as a result of anything the disciple had said but by how he behaved, the way in which he reacted.

In the centuries after the Buddha’s death, several schools based on his teachings arose. There was a very strict brotherhood of monks focused on personal liberation and salvation. But over time there also developed schools that focused upon specific sutras and composed elaborate commentaries on them. This resulted in an intellectual Buddhism that was, perhaps, more philosophical than religious. Eventually a popular devotional Buddhism also evolved, in which the Buddha came to be seen as a celestial being and in which devotees recited sutras, made offerings, and undertook good deeds in order to acquire merit that would lead to future auspicious rebirths.

These schools transmitted the Buddha’s instructions and teachings. But parallel to them, according to the Zen tradition, a school of meditation descended from Mahakasyapa in which the enlightenment experience was transmitted.

No doubt thousands of individuals attained awakening, but in each generation there was one individual whose experience was so deep that he was identified as a patriarch of the meditation, or dhyana, school. The names of twenty-eight individuals are recorded, spanning a thousand years, beginning with the Buddha and Mahakasyapa and continuing until Bodhidharma, the man credited with bringing the school to China. There the term dhyana was translated as chan. Some six hundred years later when the school proceeded on to Japan, the Japanese read the Chinese character for Chan as “Zen.”

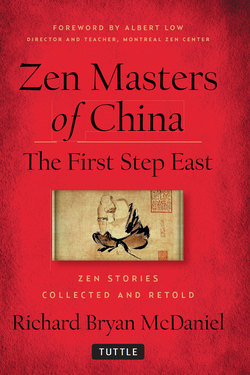

Nineteenth-century Japanese woodblock portrait of Bodhidharma