Читать книгу Zen Masters Of China - Richard Bryan McDaniel - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

BODHIDHARMA

The traditional list of Zen patriarchs is probably as accurate as the list of early popes in Christian lore. After the Buddha and Mahakasyapa, third in succession was the Buddha’s cousin and attendant, Ananda, who did not achieve awakening until after the Buddha’s death. Others in the list include historical figures such as Asvaghosha, the reputed author of The Awakening of the Faith in the Mahayana (twelfth patriarch) and Nagarjuna, the founder of the Madhyamaka school of Buddhism (fourteenth patriarch). The twenty-eighth in this lineage was Bodhidharma—a man whose name consists of the terms for wisdom/enlightenment (Bodhi) and teaching (dharma). Bodhidharma is credited with bringing the meditation school to China and is also considered the first patriarch of Chinese Zen.

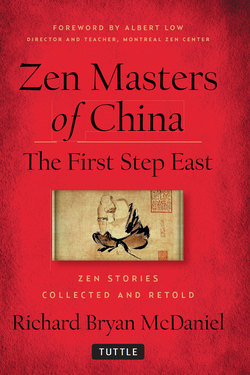

Bodhidharma is a favorite subject of Zen painting, in which he is portrayed with exaggerated features emphasizing that to the sixth-century Chinese he would have been considered a barbarian. He is shown bearded, with prominent shaggy eyebrows, large, round eyes, and often a stern expression.

It is said that he was the third son in a prominent Brahmin family from southern India. The Brahmin were the priestly caste in the Hindu tradition, the caste that studied the various scriptures and were responsible for carrying out the intricate religious rituals associated with them. But rather than assuming the role of his caste, Bodhidharma was drawn to the practice of Buddhism and eventually became a master in the meditation school under the twenty-seventh patriarch, Prajnatara.

Whereas the Hindu faith was grounded in written texts such as the Vedas and even the Buddhism of the day was transmitted through the recorded sutras, or sermons attributed to the Buddha, Bodhidharma would describe Zen in a four-line poem as:

A special transmission outside the scriptures;

Not dependent on words or letters;

By direct pointing to the mind of man,

Seeing into one’s true nature and attaining Buddhahood.

Buddhism was a thousand years old when Bodhidharma became a member of the sangha, and, in the land of its birth, the faith had deteriorated over that time, becoming more speculative and abstract. Monks spent as much or more time analyzing the sutras as in meditating. Their faith had become theoretical rather than grounded in the experience of awakening, what the Japanese would later term kensho (ken, “seeing into or understanding something”; sho, “one’s true nature”).

Nor was Buddhism a single system any longer. Competing theories and interpretations of the sutras led to a proliferation of schools, including the establishment of two broad traditions: the conservative Theraveda (the Teaching of the Elders), which spread to Sri Lanka, Burma, and Thailand, and the more liberal but also at times more fanciful Mahayana, which spread north to Tibet as well as into China, Vietnam, and Korea. It was out of the Mahayana tradition (and partially in reaction to it) that Zen would evolve.

Saddened by the condition of Buddhism in India, Prajnatara suggested that Bodhidharma travel to China and determine if that land were a suitable environment in which to revitalize Zen. It was also their intention to correct the form of Buddhism then prevalent in the Celestial Kingdom.

Buddhism had been practiced in China for over four hundred years by the time of Bodhidharma’s journey, but it was largely an academic Buddhism. Chinese scholars translated the Indian sutras and composed elaborate commentaries on them. A variety of competing schools had evolved that based their teachings on one or the other of these scriptures. Devotional Buddhism was popular with the masses. There were meditation teachers as well, but none belonged to the line of transmission descended from Mahakasyapa.

Bodhidharma was an old man when he set out for China, and it took him three long, hard years to complete his journey, traveling over both land and sea, during which time he must have learned to speak Chinese. Finally, around the year 520, he landed on the southern shore of China and from there he continued his travels on foot.

Evidence of a historical basis to the story of Bodhidharma is found in a document written by an official named Yang Xuanzhi in 547. He recorded that when he visited the temple of Yongning in Luoyang, he came upon an elderly Indian monk named Bodhidharma who claimed to be over a hundred years old. Yang noted that the monk expressed great admiration for the beauties of the shrines and other buildings he found in China.

The story of the legendary Bodhidharma does not include the visit to Luoyang but does say that eventually the Indian monk’s pilgrimage brought him to the capital city of the emperor Wu, founder of the Liang dynasty.

This emperor had been the third son of a noble family and as a young man pursued a career in military and government service, distinguishing himself as a general in the army of the emperor Ming of the Han dynasty. After Ming’s death, however, Wu led a rebellion against Ming’s son and successor. Following a prolonged siege, during which the young emperor died, Wu successfully occupied the royal palace. He had potential rivals to the throne executed, then declared himself emperor.

Although the new emperor had come to his throne by means of contrivance and violence, he proved to be a competent ruler, commended by his contemporaries for the modesty of his personal lifestyle. Around 517 he became a Buddhist, although he continued to respect the native Confucian rites as well. As a Buddhist, he adopted vegetarianism and went so far as to substitute vegetable offerings in place of the usual animal sacrifices that were ritually presented to the ancestors. In 527 he formally dedicated himself to the service of the Buddha, a commitment he renewed three more times. He even authored a repentance ritual still in use by Chinese Buddhists.

When the emperor learned that a monk from the land of the Buddha’s birth was in his kingdom, he had Bodhidharma brought to his court. The monk, however, was probably not what the emperor had expected. The naturalist, writer, and Zen practitioner Peter Matthiessen imagines Bodhidharma presenting an uncouth appearance in the court:

Cowled, round-shouldered, big-headed, bearded, broken-toothed, with prominent and piercing eyes, sometimes said to be blue—one can all but smell his hard-patched robes, stained with ghee butter from India, the wafting reek of cooking smoke and old human leather. One imagines him slouched there scratching and belching, or perhaps demanding, What time do we eat?2

The emperor was concerned about the misdeeds of his younger years and had tried to compensate for them through a variety of devotional acts. He had sponsored the translation of Buddhist texts, supported large numbers of monks and nuns, and assumed the cost of building temples. Like many devotional Buddhists, the emperor believed in karma, the concept that one’s actions bore consequences both in this life and in future lives. Eager to know if his religious activities balanced the crimes of his past, he described to Bodhidharma all he had done to promote Buddhism in his country, then asked, “What is your opinion? What merit have I accumulated as a result of these deeds?”

Bodhidharma, rejecting this simplistic understanding of Buddhism, replied bluntly and tactlessly: “No merit whatsoever.”

It was a courageous statement, because the emperor, for all his good qualities, was also known to have a temper and had the power of life and death over his subjects. A story is told that once Wu was engaged in a board game with a courtier when a monk paid him a visit. The emperor, preoccupied with his play, did not notice the monk. Making a strong move in the game, he exclaimed, “Kill!” His bodyguard misunderstood what he was saying and executed the unoffending monk before the emperor could prevent them from doing so.

On this occasion the emperor controlled himself, although he must have been angered by the old and shabbily dressed Indian’s reply. He limited himself to inquiring, “Why no merit?”

“Motives for such actions are impure,” Bodhidharma told him. “They are undertaken solely for the purposes of attaining future rebirth. They are like shadows cast by bodies, following those bodies but having no reality of their own.”

“Then what is true merit?” the emperor asked.

“It is clear seeing, pure knowing, beyond the discriminating intelligence. Its essence is emptiness. Such merit cannot be gained by worldly means.”

This was unlike any exposition of the Buddhist faith the emperor had heard before, and he asked, “According to your understanding, then, what is the first principle of Buddhism?”

“Vast emptiness and not a thing that can be called holy,” Bodhidharma replied at once.

Wu spluttered: “What does that mean? And who are you who now stands before me?”

To which Bodhidharma replied: “I don’t know.” Then he left the court.

The courtiers were outraged by the barbarian’s behavior, and it is even possible his life may have been in danger after this encounter. He traveled south, crossing the Yangtze River, some claim by floating on a reed.

After Bodhidharma had left, the emperor discussed the Indian with a local Buddhist monk named Chih Kung. Chih Kung expressed the opinion that Bodhidharma may have been the reincarnation of a bodhisattva (roughly the equivalent of a Buddhist saint), perhaps even the reincarnation of the bodhisattva of compassion, Guanyin.

The emperor, abashed that he had not recognized this possibility himself, wanted to send soldiers to retrieve Bodhidharma and bring him back to the court. But Chih Kung dissuaded him, remarking, “It will be of no use, your majesty. Were all the people of your kingdom to appeal to him, he still won’t retrace his steps.”

After crossing the Yangtzi, Bodhidharma proceeded to the Shaolin Temple located in the Songshan mountain range, which would later become famous for its affiliation with the martial arts. Bodhidharma built a hermitage on the peak of Mount Shaoshi and there practiced silent meditation while facing the wall of the cliff that rose in front of his hut. He came to be known locally as Biguan, the wall-gazing Brahmin, and the hut was known as the Wall-Gazing Hermitage.

Popular legends, not taken seriously in the Zen tradition, recount that he sat so long in meditation that his legs withered and fell off (for which reason the round-bottomed dolls weighted so that they always return upright when pushed over are known as Bodhidharma—or Daruma—dolls in Japan). Another story asserts that he became so angered after falling asleep during meditation one day that he cut off his eyelids, which then fell to the earth and grew to become the first tea plants.

Word of Bodhidharma’s audience with the emperor spread throughout the kingdom, and most members of the Buddhist community avoided the barbarian monk, leaving him in isolation. There was, however, a Confucian scholar named Ji who was searching for a teacher to help him resolve the concerns that weighed heavily on his mind—the same type of concerns that had driven the young Siddhartha Gautama to abandon his princely state in order to become a monk. Ji had visited many teachers, Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist. He studied all three traditions and was well versed not only in the Confucian classics but also in the doctrines of both the Theravada and Mahayana schools of Buddhism. Nothing, however, had brought him peace of mind. In desperation he sought out the old barbarian monk who had come from the land of the Buddha.

When Ji presented himself at Mount Shaoshi, Bodhidharma suspected his visitor was another who came seeking an intellectual explanation of Buddhist doctrine rather than the experiential insight that comes from the practice of meditation. So, for a long while he ignored Ji. The Confucian, however, remained patiently outside the hut, waiting several days for Bodhidharma to acknowledge him.

One night, it began to snow. The snow fell so heavily that by morning, it was up to Ji’s knees. Seeing this, Bodhidharma finally spoke to his visitor, asking, “What is it you seek?”

“Your teaching,” Ji told him.

“The teaching of the Buddha is subtle and difficult. Understanding can only be acquired through strenuous effort, doing what is hard to do and enduring what is hard to endure, continuing the practice for even countless eons of time. How can a man of scant virtue and great vanity, such as yourself, achieve it? Your puny efforts will only end in failure.”

Ji drew his sword and cut off his left arm, which he presented to Bodhidharma as evidence of the sincerity of his intention.

“What you seek,” Bodhidharma told him, “can’t be sought through another.”

“My mind isn’t at peace,” Ji lamented. “Please, master, pacify it.”

“Very well. Bring your mind here, and I’ll pacify it.”

“I’ve sought it for these many years, even practicing sitting mediation as you do, but still I’m not able to get hold of it.”

“There! Now it’s pacified!”

And at these words—as when Mahakasyapa saw the Buddha twirling the flower between his fingers—Ji came to awakening. He came to the same experiential understanding that the Buddha, Mahakasyapa, and all the patriarchs before Bodhidharma had attained—that his basic nature, his “Buddha-nature,” was no different from that of all existence. In acknowledgment of this attainment, Bodhidharma told him that henceforth his name would be Huike, which means “his understanding will do.”

Bodhidharma remained at Shaolin for nine years, during which time only a few aspirants sought him out. His teaching was based on the practice of meditation and the attainment of awakening, but (in spite of his emphasis that Zen was a tradition “outside the scriptures and not dependent on words and letters”) he also introduced his students to the Lankavatara Sutra. It would be his followers and descendents who would mold the old Brahmin’s teaching into something thoroughly grounded in Chinese practicality.

In spite of the fact that he had only a handful of disciples, his teaching angered members of other Buddhist sects, and it is said that six attempts were made to poison him, all of which he thwarted.

Eventually Bodhidharma decided to return to India, and, in preparation for his departure, he called his chief disciples together and asked each of them to give him their understanding of the teaching of the meditation school.

The first to reply was a monk named Dao Fu, who said, “Reality is beyond yes and no, beyond all duality.”

Bodhidharma told him, “You have my skin.”

The second to speak was a nun, Zong Chi. “To my mind, truth is like the vision Ananda had of the Buddha-lands, glimpsed once and forever.”

Bodhidharma told her, “You have my flesh.”

Next came Dao Yu: “All things are empty. The elements of fire, air, earth, and water are empty. Form, sensation, perception, ideation, and consciousness—all of these also are empty.”

Bodhidharma told him, “You have my bones.”

Finally, there was only Huike. When Bodhidharma turned to him, Huike bowed and remained silent.

“Ah,” Bodhidharma exclaimed in admiration. “You have my marrow.”

Some accounts put Bodhidharma’s age at 150 by the time he decided to return to India. In one account, he died en route and was buried by Huike in a cave on the banks of the Luo River.

One more story, however, is told of him.

A government official named Song Yun claimed that as he was returning to China from a visit to Central Asia he met Bodhidharma proceeding in the opposite direction, barefoot and carrying one sandal in his hands. When Bodhidharma’s disciples heard this account, they opened the patriarch’s tomb and found it empty except for a single sandal.

Huike meditating