Читать книгу On Common Ground - Richard D. Merritt - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 5

ОглавлениеNavy Hall

Below the ramparts of Fort George near the edge of the Niagara River, the long, low stone-clad building known as Navy Hall is a popular venue for various social gatherings and educational events. Inside, the exposed hand-hewn beams, interior shutters, and welcoming fire in the huge stone fireplace evoke an ambiance of two centuries ago. Through excellent interpretive displays on the walls, visitors may learn the Navy Hall site is nearly 250 years old. The Navy Hall wharf, now a popular perch for amateur fishermen and the occasional mooring site for commercial marine enterprises, has been a naval and public dock for a similar period. In recognition of its rich and colourful past, Navy Hall was designated a National Historic Site in 1969.

In its formative years, the isolated Fort Niagara was completely dependent on sailing ships bringing in provisions, ammunition, and reinforcements across Lake Ontario from the St. Lawrence River, and later from the more easterly outpost of Oswego. The wharf below the fort was busy and several vessels were built there. However, the site was not ideal, and by late 1765 the British commander of Fort Niagara reported that “they [Naval Department] have been building a Navall Barracks 1200 yards above this Fort upon the opposite side of the river; they have also begun a warfe [sic] there.”[1] It was easier for tall-ships to get underway from the west side of the river, the site was more protected for ship-building and wintering, plus there was a ready supply of oak beyond the grassy plain above. Initially, the building consisted of a barracks for seamen and a room for officers and was set at right angles to the shoreline. In order to accommodate increased naval activity during the American Revolutionary War, more barracks, a “house,”[2] and outbuildings including a “rigging and sails loft” were added. The shipyard was busy repairing and building various new vessels for the Provincial Marine and private merchants. The first official use of the name “Navy Hall” appeared in a memorandum in May 1778,[3] but it actually referred to the general area and the complex of buildings on the site.[4] Under the terms of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the British would eventually have to cede Fort Niagara to the Americans. Almost immediately Governor Haldimand directed his surveyors to reserve the plain above Navy Hall for a protective military post[5] (see chapter 8).

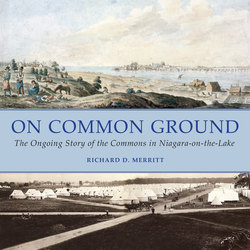

A View of Niagara Taken from the Heights Near Navy Hall, artist James Peachey, watercolour, 1783 or 1787. This painting clearly shows a portion of Navy Hall at the water’s edge and British-held Fort Niagara across the river. The open grassy plain on the left with the Rangers’ Barracks in the distance, although already reserved for military purposes, is being used as common lands. Library and Archives Canada, James Peachey collection, C-002035.

By 1788 the buildings were already “in exceeding bad repair,”[6] so when Lieutenant Governor Simcoe arrived in the summer of 1792, he immediately ordered an extensive renovation of Navy Hall (by then only the original building was still standing) as a residence for his family and for government offices. He complained to a friend back in England that for accommodation he was “fitting up an old hovel that will look exactly like a carrier’s ale-house in England when properly decorated and ornamented.”[7] While waiting for the renovations to be completed, the Simcoes lived in marquee tents and later the canvas house on the plain just above Navy Hall, which they much preferred. During hot Canadian summer evenings, they would sit outside their canvas tents to catch the breezes. We generally think of the first Lieutenant Governor as one of strict formal military bearing; his wife a young reserved, though proud, wealthy heiress. Yet while writing a letter to Charlotte, one of his daughters who remained back home in England, Simcoe portrays a very relaxed informal domestic scene: sitting in an oak bower on the edge of the Commons (now the site of Fort George), the little family was thoroughly enjoying one another’s company as well as the vista to Navy Hall below, the expansive river, and Fort Niagara beyond.[8] Panting at their feet also trying to keep cool would have been their huge “borrowed” Newfoundland dog, Jack Sharp, who was a frequent fixture at Navy Hall during the Simcoe era.[9] When the first member of the Royal Family to visit Upper Canada, Prince Edward, the Duke of Kent,[10] arrived, he chose the canvas accommodation and hence the Simcoes were reluctantly forced back into the “miserable … damp”[11] Navy Hall. Despite the limitations of the old building itself Mrs. Simcoe enjoyed the property with its vistas across the river, the fine turf of the commons, and the woods beyond (known today as Paradise Grove) where she often took walks. She was especially pleased with “thirty large May Duke cherry trees behind the house, and three standard peach trees.”[12]

Lt. General Simcoe, artist Jean Laurent Mosnier, oil painting, 1791. John Graves Simcoe (1752–1806) commanded the Queen’s Rangers, First American Regiment, during the American Revolutionary War. Upon his appointment as the first Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada in 1791, Simcoe returned to North America and chose the tiny community opposite Fort Niagara as the first but temporary capital of the province. For the next four years the Navy Hall complex served as his home, administrative offices, and base of operations. Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library, Toronto Reference Library, #T 30592.

Elizabeth Posthuma Gwillim Simcoe (1762–1850), artist Mary Anne Burges, watercolour. Elizabeth, through her letters, diaries, and sketches portrayed many aspects of life in Niagara and Upper Canada during her husband’s tenure as Lieutenant Governor of the province. Library and Archives Canada, C-095815.

In order to accommodate a growing bureaucracy, several more buildings were erected on site. During the four years Niagara was the temporary capital of Upper Canada, most official government correspondence originated from Navy Hall. Moreover, thousands of hopeful but apprehensive settlers went there with their petitions for land grants. But the old building was much more than a sterile government office; several well-attended “splendid balls” lasting through the night were held there, as well as grand levees. Even visiting American diplomats were impressed.[13]

With the transfer of the government to York in 1796, the bureaucracy reluctantly followed across the lake as well. Simcoe’s offices were converted into the officers’ mess for Fort George while the other buildings in the complex were used by the Provincial Marine and for commissariat stores. During the tremendous bombardment from the American guns at Fort Niagara and their river battery in November 1812, the original building at Navy Hall was “entirely consumed.”[14] It is believed the rest of the buildings were totally destroyed during the American bombardment just prior to their successful invasion the following May.

Navy Hall from the Fort of Niagara, artist Elizabeth Simcoe, sketch on paper. The verdant plain and woods above the Navy Hall complex are readily visible. Archives of Ontario, Simcoe family fonds, F 47-11-1-0-13.

Within a year of cessation of hostilities, construction began on a new frame “commissariat store at Navy Hall.”[15] Rebuilt on the same location, but slightly smaller at one hundred feet by twenty-five feet, it was complemented by a new “King’s Wharf” as well. In 1840, the building was fitted as a barracks to accommodate seventy-two men.[16] Meanwhile, a cross-river ferry was operated from the Navy Hall wharf with a customs house, guard house, and the “Ferry House” tavern nearby. The area was very much in the public domain. By the 1850s the barracks shown on maps as either the Red Barracks or Ferry Barracks had been relegated to storage use again. For a short time during the American Civil War, nine married couples of the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment occupied the premises.[17]

In 1864, to accommodate a spur line of the Erie and Niagara Railway, the building was ignominiously moved across the road closer to the ruins of Fort George[18] where it was allowed to deteriorate. By the turn of the century the old building was being used as a stable and cow barn and appeared to be about to collapse. Historians, erroneously believing that this building had survived the War of 1812 and had been the actual site of the first parliament of Upper Canada, petitioned the federal government to restore Navy Hall. A small injection of federal funds supplemented by a bequest of the publisher and historian John Ross Robertson stabilized the building, and a marble plaque was erected.

Inoculation in the First Parliament Building in Canada, Niagara Camp 1915, photo postcard, 1915. Soldiers are lined up at the partially restored Navy Hall, patiently waiting for their inoculations prior to being shipped out to Europe. Courtesy of the author.

During the Great War the partially restored building was converted into a laboratory for the Canadian Medical Corps to test the Niagara River water supply for Camp Niagara. Other uses included a six-chair clinic for the Dental Corps, stores for medical supplies, and as an inoculation site. Abandoned after the war, the building deteriorated again. In the midst of the Great Depression, local Boy Scouts and Girl Guides occupied the old building until finally in 1934 the Niagara Parks Commission (NPC) reached an agreement with the federal Department of National Defence. As a make-work project, the NPC would restore Navy Hall and Forts George and Mississauga with federal funds, in return for a ninety-nine-year lease “with rental set at an affordable $1.00 per year”[19] (see chapter 8). The rarely used railway spur line had been removed two decades earlier, allowing the old ramshackle building to be moved back to its original site.[20] Actual reconstruction began three years later in 1937. It was set on a new stone foundation with a full basement and encased in stone to protect it from the elements.[21] Many of the original beams had deteriorated, and so a number of beams salvaged from an old barn in Niagara Falls were used in the restoration. All the work was completed by the next summer. To provide vehicle access to Navy Hall, the Niagara Parkway was eventually extended from its intersection with John Street in Paradise Grove along the river to the Navy Hall site. Ricardo Street was extended from the northwest. The small frame one-and-a-half storey Customs House was also restored at this time. Also clad in stone and now situated on the Fort George side of Ricardo Street it is currently used for offices of Parks Canada employees. A new wharf was built to accommodate a proposed shuttle service between Forts George and Niagara, although this never really materialized. Nevertheless, the locals and tourists alike could now enjoy the river site of Navy Hall once again. In 1969, the NPC relinquished its lease to Parks Canada. The wharf was upgraded in 1977[22] and later the building was refurbished and the interpretive displays installed within. Today the restored 1816 commissariat store is a popular site for both indoor and outdoor social gatherings … and on a hot summer’s evening, one might see a young family sitting with their dog on the grassy rise above Navy Hall enjoying the view across the river.

Navy Hall today, photo, 2011. The restored 1816 commissariat building clad in stone (1930s). The fortifications of Fort George are barely visible on the rise above.

Courtesy of Cosmo Condina.