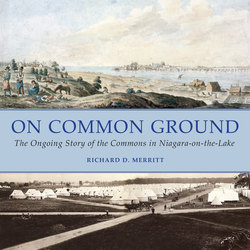

Читать книгу On Common Ground - Richard D. Merritt - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 4

ОглавлениеA “Commodious Dwelling” on the Commons

Standing in the tall, wild grass in the middle of the Commons on the edge of a small creek,[1] it is hard to imagine that a fine Georgian estate stood there as early as 1793. “Springfield” was the home of Peter Russell, a veteran of the Seven Years’ and American Revolutionary Wars and an inveterate gambler. As the newly appointed Receiver General for the Province of Upper Canada, Russell arrived at Niagara in 1792 with his half-sister Elizabeth and a young Mary Fleming (possibly Peter’s illegitimate daughter).[2] The only accommodation they could find “near the Lieutenant Governor’s Residence at Navy Hall”[3] was a two-room “hut”[4] in the middle of the Military Reserve occupied by Widow Murray, for which Russell paid £70.[5] Lieutenant Duncan Murray had been an officer in the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants), garrisoned during the early 1780s across the river at Fort Niagara.[6] While building grist and sawmills on his land grant on the Twelve Mile Creek[7] in 1786, Murray was killed by a falling tree. Perhaps in deference to her late husband, Widow Murray was allowed squatter rights in the middle of the reserve. Russell, realizing that the £70 purchase price was for Mrs. Murray’s improvements only, persuaded Simcoe to grant him a twenty-one-year lease for fifty acres, which included the Widow’s farm, at a nominal five shillings per year.[8] He also received an outright grant of 160 acres of prime land bordering the southern edge of the military reserve, along what is now John Street, that he would later sell for a very tidy profit.

Peter Russell (1733–1808), artist G.T. Berthon, watercolour. Russell, army officer, office holder, politician, and judge, was also the builder of Springfield on the Fort George Military Reserve/Commons. Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library, Toronto Reference Library, John Ross Robertson Collection, JRR #T34630.

Before winter set in, the Russells undertook extensive renovations to the hut. Peter complained of the “extravagant wages”[9] of the workmen, with carpenters demanding 7 shillings per day.[10] Within the first year they had already spent £400[11] and by 1796 Russell claimed to have spent £1200[12] on improvements, which included his governmental office on the premises. No exterior views of the house have survived, but a plan of the property drawn in 1797[13] reveals a full two-storey house, along with a coach house, stables, outhouses, root house, and cellars, as well as a formal fruit garden at the rear. Even a spring is shown on the plan. This may explain the name of Springfield, since the fields of the military reserve surrounded the estate. Despite much grumbling about the costs of their “Dear House” the little family seemed to have been very comfortable in their new home. In a letter to a friend in England, Elizabeth wrote:

We are comfortably settled in our new House and have a nice little farm about us. We eat our own Mutton and Pork and Poultry. Last year we grew our own Buck wheat and Indian corn and had two Oxen, got two Cows with their calves with plenty of pigs and a Mare and Sheep.[14]

Elizabeth’s fruit preserves became a much sought-after commodity amongst her fellow colonists. Even Mrs. Simcoe admired Elizabeth’s hobby of collecting and preserving botanical specimens gathered in the area.

Not interested in the whirl of social activities at Navy Hall, the Russells were content with small, intimate dinners at Springfield served on the family silver plate, accompanied by fine wines and followed by sonorous renditions given by Peter. This “little threesome” in the commodious house could not possibly have managed without help. The practice of slavery was still alive and well on the Commons in the 1790s. Peter had at least two manservants, Robert Franklin and Pompador. There were also at least two maids/cooks, including Milly and the “troublesome” Peggy. Russell’s attitude towards slavery was hypocritical. Although he supported Simcoe’s anti-slavery legislation through parliament,[15] and later as administrator of the province prevented an attempt to reverse the legislation, he owned at least five slaves. He paid for a tutor to teach the son of one of his slaves to read and write, and yet in 1806 he put Peggy and her son Jupiter up for sale.[16]

Well-established in her “commodious dwelling house,” Elizabeth Russell commiserated with the Simcoes who had “only a Canvas House”[17] to shelter them from the inclemency of the Canadian weather.

Government officials were well aware of Simcoe’s determination to move the temporary capital of Upper Canada across Lake Ontario to York, with the new parliament opening there in 1797. Many government officials were slow to make the move, and quite agreed with Elizabeth who proclaimed, “For my part I am determined to stay here where I am till there is a comfortable Place there to receive me.”[18] Eventually, her brother, who had by then been named administrator of the province with Simcoe on sick-leave in England, would find a suitable abode in York. However, the prospect of moving created a major quandary for Peter: how could he possibly recoup his investment in Springfield when he still did not have clear title to the property? One can clearly detect an air of desperation in his correspondence to the new Governor General Robert Prescott, in which Russell suggested that the military reserve need not be so large; if the reserve were to be reduced in size, his property would be outside the reserve and hence his land could be held in freehold.[19] In reply he received a harsh reprimand from Prescott’s secretary for even suggesting a change in the military reserve. Moreover, he was advised that the lease was invalid and he had no right to build on the land and would have to remove his house from the reserve.[20] To add to his woes, his new house in York for which he had paid £400, had “just burnt to the ground,”[21] putting his sister “in a low nervous state.”[22] In the end, the Governor General relented and permitted the much-chastened Russell to continue to lease the property on the military reserve. In an effort to sell his leased property in Niagara, Russell placed a large advertisement in the November 1796 edition of the Upper Canada Gazette for “A Commodious Dwelling, coach house, stable and other offices all built within three years.”[23] He commissioned Lieutenant Robert Pilkington of the Royal Engineers to draw up “a Plan of the Premises of Mr. President Russell,”[24] which apparently was quite widely distributed. After one year on the market the balance of the lease and the buildings thereon were conveniently taken over by the British Indian Department as a dwelling quarters for its officers at £900.[25]

Plan of the Premises of Mr. President Russell, artist Robert Pilkington, 1797, sketch (a 1915 copy of the original in Library and Archives Canada, NMC 0023040). On his fifty-acre leased property in the middle of the Fort George reserve, Russell erected a two-storey “commodious dwelling” with cellars, several outbuildings, plus an extensive garden. Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #986.006.

The British Indian Department was created by the British government in the 1750s as the Crown’s military liaison with the Native tribes in North America (see chapter 7). It had initially been concerned with mobilizing His Majesty’s Indian Allies against the French during the Seven Years’ War. Subsequently during the American Revolutionary War, the Indian Department worked diligently to direct the First Nations against the rebelling colonists, especially along the western frontier. Even after the Revolution, the British maintained this “chain of friendship” with the Natives, keeping them “on side” leading up to the War of 1812 when His Majesty’s Indian Allies would play a pivotal role in several battles.[26]

With the Americans’ takeover of Forts Niagara, Detroit, and Michilimackinac in 1796 in accordance with Jay’s Treaty, the Indian Department was reorganized. It built new Council Houses at Fort George, Fort Malden on the Detroit River, and Fort St. Joseph in the northwest, each with its own officers, including a superintendant of Indian Affairs, a storekeeper/clerk, and interpreters. The timely availability of Russell’s house and fifty acres in the midst of the military reserve was a perfect fit for the needs of the Indian Department: the new Council House, storehouses, blacksmith, and other out-buildings on one side of the creek and the officers of the Department ensconced in the “Commodious Dwelling” on the other.

What a sharp contrast between the two households: from the hesitant yet arrogant bachelor-bureaucrat Peter Russell, his gossip-prone, haughty spinster half-sister, and the quiet, young but frail teenage Mary,[27] supported by a household of several slaves, replaced by the boisterous and lusty backwoodsmen employees of the Indian Department. No doubt the house was renovated to meet the needs of the Department. In addition to several bedrooms there would have been an office for the superintendant, a dining/meeting room, a kitchen in a separate building, and a large common room. There, whoever happened to be in town on Department business would probably gather around the fireplace, exchange news and gossip, recall exploits, and perhaps tell some very tall tales, all the while puffing on clay pipes and throwing back swigs of rum or brandy. Raucous games of cards, dice, checkers, or backgammon would have been other popular pastimes. The air would have been heavy with wood and tobacco smoke mixed with the smell of tallow candles and rancid body odours. The common room’s walls were probably decorated with maps and proclamations, prints and sketches, portraits of George III and other members of the Royal family, and many colourful and curious Native artifacts.

Effective December 25, 1797,[28] the following Indian Department officers were appointed at Fort George: William Claus, superintendant; Robert Kerr, surgeon; William Johnson Chew, storekeeper and clerk; Barnabas Cain, blacksmith; and George Cowan, David Price, John Norton, and Jean Baptiste Rousseaux as interpreters.[29] Although it is highly unlikely that all these men were assembled together at Niagara at one time, as a group they arguably represent the most colourful and remarkable collection of individuals ever to occupy the Commons or its perimeter.

William Claus

Born into a family of wealth and privilege in the Mohawk Valley, William Claus was a grandson of Sir William Johnson, the powerful Superintendant of Northern Indian Affairs. His father, Christian Daniel Claus, also held important positions in the Indian Department. William’s formal education was interrupted by the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. He enlisted as a volunteer in the King’s Royal Regiment of New York under the command of his uncle, Sir John Johnson. After the war, he obtained a lieutenancy in a regular British regiment, the 60th Foot, and made captain by 1795. Meanwhile Uncle John, who was now Superintendant General of Indian Affairs, anxiously sought a position for young William in the Department. With the death of John Butler in 1796, Claus was finally appointed deputy superintendant at Fort George and four years later named Deputy Superintendant General for Upper Canada — a post he held for the next twenty-six years.

William Claus (1765–1826), artist and medium of portrait, unknown. Claus was a grandson of Sir William Johnson, an army officer, office-holder, deputy superintendant of the British Indian Department for Upper Canada, builder of what became known as the Wilderness, and a horticulturalist. Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum, #984.1.559

Although much of Claus’s official time in the service involved “the interminable tedium of Indian councils, gift giving and pledges of British friendship,”[30] Claus was confronted by several major challenges. Captain Joseph Brant, civil and war chief of the Six Nations, insisted the Natives of the Haldimand Tract of the Grand River had the right to sell off some of their lands. Claus, acting on behalf of the colonial government, countered that the Six Nations did not have free sovereignty of their land and hence could only sell their land back to the Crown.[31] Although a partial compromise was eventually found, the land ownership issue continues unresolved today.

With the increasing belligerence of the War-Hawks within the United States, Claus was kept busy trying to polish the chain of friendship with the Six Nations and Western Indian Allies in order to keep the Natives “on side.” Opposition to his influence within the Six Nations came from an unexpected source. Former employee and sometime fellow occupant in the Commodious House, interpreter John Norton, was persuaded by Joseph Brant to leave the service and move to the Grand Valley where he quickly became Brant’s confidant and eventual successor. During the War of 1812, impressed by Norton’s outstanding military acumen and leadership skills, the British Army generals deferred to Norton rather than Claus, and by early 1814, commander-in-chief Sir George Prevost proclaimed that Norton was to be the sole spokesman and dispenser of gifts to the Six Nations and Thames Natives until the end of the war.[32] Embarrassed and humiliated, Claus became consumed by jealousy and loathing of Norton’s influence, constantly trying to undermine Norton’s reputation. The intense rivalry between the two men only diminished after Norton was pensioned off and was succeeded by the young John Brant.

The post-war years were also characterized by a major shift in British colonial policy towards the Natives from one of “allies” to mere wards of the state — a transition supervised by Claus, but a role he played with efficiency and compassion. He was appointed to the prestigious Executive Council of the Province, named a Justice of the Peace, and he served as a school trustee and commissioner of customs.

Although he probably maintained an office in the officers’ quarters, it is unlikely that Claus ever intentionally slept over in the officers’ quarters; he had inherited his mother’s town lots[33] on the edge of the military reserve, where he raised a family. He and his wife, Catherine, kept careful notes of their gardening efforts which provide an interesting glimpse of horticultural practices in early Upper Canada.[34] He died in 1826 after a slow, agonizing battle with disfiguring lip cancer.

Doctor Robert Kerr

Robert Kerr was born circa 1755 in Scotland, and soon after his arrival in North America became a hospital mate in the King’s Royal Regiment of New York during the Revolutionary War. In 1788 he was appointed Surgeon to the British Indian Department, no doubt in part due to his fortuitous marriage to Elizabeth, daughter of Sir William Johnson and the indomitable Molly Brant. Settling in Niagara the following year, he attended diligently to his duties with the Indian Department, but also served at times as surgeon to the various regiments garrisoned at Fort George. He also had a large private practice in town. In 1797 he and fellow physician James Muirhead advertised the availability of small pox inoculation for the townspeople, “the poor gratis”[35] — one of the first examples of preventive medicine in Upper Canada.[36]

Dr. Robert Kerr (1755–1824), attributed to E.Wyly Grier, watercolour over pencil on paper. Kerr served as surgeon to military regiments and the British Indian Department, town physician, judge of the Surrogate Court, and deputy grand master of the Provincial Grand Lodge of Masons. He married Elizabeth, daughter of Molly Brant and Sir William Johnson. Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library, Toronto Reference Library, John Ross Robertson Collection, JRR #T14843.

The doctor had built a substantial house in town for his growing family,[37] so it is unlikely that he actually stayed in the commodious house on the Commons, but he would certainly have attended to ailing Department employees there as well as any visiting Natives. In his war loss claims Kerr lists his medical instruments at the Indian Council House as having been destroyed.[38] Kerr was also a prominent freemason, serving as provincial grandmaster for a remarkable thirteen years. Tall and well proportioned, he enjoyed sports, particularly boxing. Like other early medical men, he supplemented his income with government appointments, serving as a judge of the Surrogate Court, a Land Board member, commissioner of the peace, and trustee for public schools. As one of the earliest physicians of Upper Canada, Kerr was much beloved and respected by the Natives, soldiers, and citizens alike.

William Johnson Chew

William Johnson Chew, born in that fateful year of 1759, was appointed through the influence of his father, Joseph Chew, who had served ably as secretary to the Indian Department. Young William “behaved with attention to his Duties,” starting in 1794, although he was “not much conversant with the Indian language.”[39] As storekeeper he was responsible for all of the Departmental supplies, as well as the presents and trade goods for the Natives. As clerk he would attend the Indian councils to accurately record the speeches and any resultant agreements. On the morning of May 27, 1813, serving as an officer in the Indian Department with fifty Natives under Captain John Norton, he was killed trying to prevent the American landing at One Mile Creek.[40] Chew married Margaret Mt. Pleasant, whose mother was a Tuscarora Native.

Barnabas Cain

Barnabas (Barney) Cain is listed as a sergeant in the Indian Department.[41] He was granted town Lot 39 in Niagara, as well as Lots 111 and 114 in Niagara Township (near Virgil). He later served in the Lincoln militia at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane and is said to have carried off the battlefield the lifeless body of his friend George Caughill.[42] As the Department’s blacksmith he would have been kept busy forging a variety of iron hardware, as well as shoeing horses for the employees and the Natives. In some provincial locales the blacksmith also repaired guns and instruments. The smithy was situated by the Council House. Newly remarried in February 1798 by Reverend Robert Addison,[43] he probably hurried home to his new bride, Cyble Clinton, rather than linger about the commons in the evenings.

Interpreters

Interpreters were chosen for their language skills and trustworthiness. At least one and often two interpreters would be present at the various Indian Council meetings, whether at the Council House at Fort George or at meetings held elsewhere such as Buffaloe Creek,[44] Burlington Heights, or the Grand Valley. On occasion they would be sent out as special emissaries or on secret missions. Given their backwoods origins, most interpreters probably preferred to sleep under the stars by a smoking fire, accepting the housekeeper’s invitation to bed down indoors only in inclement weather. Later there may have been separate quarters for the interpreters over by the Council House.

David Price

Born of Welsh parents in the Mohawk Valley in 1750, David Price was captured by the Senecas in 1771 and lived amongst them for seven years. During the American Revolutionary War he served with the much-feared Brant’s Volunteers,[45] which consisted of both Natives and whites who fought together under Joseph Brant “in the Indian Fashion.” After the war, he became an interpreter first at Oswego and later Fort George. In 1800 he married Margaret Gonder, daughter of loyalist Michael Gonder, who lived on the upper Niagara River. This “old zealous Servant of the King”[46] left the service circa 1812 and took up farming along the Chippawa Creek until his death at ninety-one years.

George Cowan

Probably of Scottish ancestry, Cowan was captured as a young boy by the French at Fort Duquesne (Pitt) in 1758, became fluent in French, and at times assumed a French name, Jean Baptiste Constance or Constant.[47] Although he served on at least one occasion as an interpreter for the Americans in the Ohio Valley,[48] he became a fur trader, guide, and interpreter for the British, establishing a trading post on Matchadesh Bay on Lake Huron. As the guide for Lieutenant Governor Simcoe when he trekked through the region in 1793, Cowan pointed out the ideal site for the future strategic harbour of Penetanguishene.[49] Cowan was considered one of the best Chippewa and Mississauga interpreters in the colony. Whenever these tribes visited the Indian Council House at Fort George he would be summoned. In 1804, a Chippewa chief accused of murder and accompanied by Cowan as an interpreter was being transported aboard the schooner HMS Speedy for trial in Newcastle on Lake Ontario. All aboard, including the judge, the Solicitor General for Upper Canada (prosecutor), a member of the Assembly (defence lawyer), the high constable, and several others were lost when the Speedy went down in a violent storm.

John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen)

Norton was born in Scotland in 1770, the son of a Scottish mother and a Cherokee father who as a young boy had been rescued by a British officer from a burning village in America. Based on his future writings and great oratory skills, John received a good education before enlisting as a private in the British 65th Regiment of Foot, which arrived in Quebec in 1785. One year later his regiment was posted at Fort Niagara where Norton soon became enamoured with the Native people. Leaving the army shortly thereafter, he served as a schoolmaster for Native children at Deseronto for one year before heading west. Hired by Detroit merchant John Askin, Norton acted as interpreter and fur trader at various trading posts in the Ohio Country and the Old Northwest. With the defeat of the British and their Native allies at Fallen Timbers, he returned to Niagara and was appointed interpreter to the Indian Department. Based on records of Indian councils, Norton appears to have been the most active interpreter and emissary, hence, he probably spent considerable time at the commodious dwelling. Norton soon caught the eye of Captain Joseph Brant, who eventually convinced him to resign from the Indian Department and work with him amongst the First Nations of the Grand Valley. Soon he was adopted as a Mohawk nephew of Brant and given the name Teyoninhokarawen. Brant sent Norton on a secret mission to Britain in 1804 to press the Six Nations’ land claims. He was unsuccessful in his prime objective, but the trip was a personal triumph for Norton as he was introduced to reformers and abolitionists as well as the nobility and even the Prince Regent.

Tall, handsome, gregarious, fluent in four European languages and twelve native dialects and blessed with a remarkable memory and oratorical skills, he truly had charisma. He was equally at home in the small intellectual gatherings of the reformers and the grand drawing rooms of the wealthy upper-class of Britain as he was in the frenetic war dances of the First Nations. Before returning home, the newly formed British and Foreign Bible Society convinced him to undertake their very first transcription effort: the translation into Mohawk of the Gospel of St. John, a remarkable feat accomplished in less than three months. Shortly after his return to the Grand Valley, Joseph Brant died. Norton assumed Brant’s role as a chief of war and diplomacy, introducing reforms in agriculture, industry, education, religion, and social welfare to his adopted people. Although supported by the majority of the chiefs and matrons, the Indian Department and his old protégé William Claus, encouraged by colonial officials at York, constantly tried to undermine his authority. They questioned his parentage, his motives, his chosen way of life — yet the more they attacked his integrity, the stronger his stature became.

John Norton, Teyoninhokarawen, the Mohawk Chief (1770–circa 1830), artist Mary Ann Knight, miniature watercolour on ivory, 1805. He was appointed an interpreter with the British Indian Department at Niagara in 1796 but three years later he was persuaded by Chief Joseph Brant to move to the Six Nations Tract on the Grand River. Note his silver earrings or ear bobs and the many trade silver brooches on his shirt. Library and Archives Canada, C-123832.

In 1809 Norton undertook an odyssey to the land of his Cherokee ancestors in the southern United States where he became acquainted with relatives of this father. He also recorded the legends and lore of the Cherokees as well as their modern adaptation to the incursions of the Europeans.

Back in the Grand Valley, Norton resumed the military leadership[50] of the Six Nations, a position he held throughout the War of 1812; after Tecumseh’s death in 1813 he also led His Majesty’s Western Native Allies. In addition to Detroit, Norton fought at every major battle but one in the Niagara Peninsula. His military acumen and leadership skills, particularly at Queenston Heights, received glowing praise from British Army generals, and yet the Indian Department, increasingly alarmed at his growing stature, continued their attempt to undermine his integrity and authority among the Natives. By early 1814, however, commander-in-chief Sir George Prevost proclaimed that therein Norton was to be the sole leader and dispenser of gifts among the Six Nations and Thames allies until the end of the war[51] — an unprecedented acknowledgement of Norton’s abilities and accomplishments and a total repudiation of William Claus and the Indian Department.

Shortly after the war, Norton with his wife and young son returned to Britain where he was welcomed as a hero — gazetted a brevet major in the British Army, granted a lifetime pension, and awarded personal gifts from the Prince Regent (future George IV) himself. While in Britain he completed his monumental journal dedicated to Northumberland, who was to arrange to have this important work published in Britain. Unfortunately the Duke died shortly thereafter and the manuscript sat on a library shelf nearly forgotten until after the Second World War when it was discovered and eventually published by the Champlain Society.[52] The journal consists of three sections. The first describes his trip to the land of his Cherokee ancestors in which he records details of Cherokee mythology, history, customs, social conditions, and even sports — the accuracy of which has been confirmed by later historians and ethnologists. The second section is devoted to the history of the original five Iroquois nations and contains much heretofore unknown information which had been collected by Brant but subsequently lost and hence is of enormous scholarly importance. The final section is Norton’s personal and amazingly accurate narrative recollection of the War of 1812. As such the journal is certainly the most important and by far the most detailed account of the War of 1812 from a Native perspective and is arguably the most comprehensive personal account of the war from the British side as well.

Back on the Grand River again, Norton managed a large farm, constantly extolling to his neighbours the rewards of good agricultural practices and the virtues of good “Christian living.” He was also indefatigable in promoting the war claims of his fellow Native war veterans and their families.

In 1823 he became involved in a duel over alleged infidelities by his wife. His protagonist was killed: rather than sully his wife’s reputation Norton pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was assessed a fine. Greatly shaken, Norton settled his affairs and headed south again, never to return to British North America which he had so strenuously helped to preserve. In 2011 the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada designated Norton as a National Historic Person.

St.Jean-Baptiste Rousseaux

St.Jean-Baptiste Rousseaux was born in Quebec in 1758. As early as 1770 his father was trading with Natives at the mouth of the St. John’s Creek, later known as the Humber River on Lake Ontario. Soon Jean-Baptiste was carrying on this trade and serving as an Indian Department interpreter with the Mohawk and Mississauga tribes. By 1792 he had established a store on the Humber. The following year he welcomed the Simcoes, who arrived to explore and proclaim the site as the future capital of the province. As such, Rousseaux is considered one of the founders of the city of Toronto.[53] A restless but enterprising soul, he later moved to the Head of the Lake (present day Hamilton Harbour) establishing a general store and later an inn, blacksmith shop, and extensive grist and sawmills at Ancaster. Meanwhile, he continued as an interpreter and respected adviser on Native affairs, hence his appointment at Fort George. Prior to the War of 1812 he was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the militia. Present at the Battle of Queenston Heights, one month later he contracted pleurisy, and despite the efforts of his friend and physician Doctor Kerr, he died at Fort George (possibly in the commodious house) and was buried with full military honours in St. Mark’s churchyard.[54]

Many visitors would have been welcomed to the commodious house. The Superintendant General, Sir John Johnson, who occasionally toured the Department’s sites, would have expected special attention. Commissioned officers of the Indian Department and veterans of the American Revolutionary War probably dropped in for a little refreshment and camaraderie in the common rooms.

The transfer of Springfield from the Russells to the Indian Department was not quite as smooth as originally planned. Apparently when the Russells departed for York, several army officers took up residence in the vacant premises and were quite incensed when forced to give up their commodious dwelling to officials of the Department.[55] This underscored the ongoing friction between the officers of the British Army, who were primarily from the privileged class in Britain, and the officers and men of the Department, who had spent their entire adult life in North America. Moreover, many of the latter had married into Native families and were much more sympathetic to the First Nations’ cultures and perspectives.

Departmental officials also had to deal with other intruders. Townsfolk who regarded the military reserve as their commons were helping themselves to the extensive gardens and orchards on the premises, hence they were told explicitly that “Towns people can have nothing to do with it (any) more than the King can interfere with their property without previous consent.”[56]

One gentleman who was welcome was the garrison’s commissariat officer. With no space for his offices in the new fort, he was permitted to use one of the outbuildings on the estate.

Although some of the buildings of the Indian Department were destroyed by the bombardment of Fort George in May 1813 and the subsequent occupation by the Americans, a post war map (1817) of the military reserve[57] indicates a building very near the site of the original commodious dwelling’s stable, so it may have survived the war, at least in part. It is labeled “Commandant Quarters,” which makes sense as it is halfway between the crumbling but still occupied Fort George and Navy Hall to the east and the new Butler’s Barracks complex being built to the west. The twenty-one-year lease had expired and the much diminished Indian Department no longer had any need for the building and was gradually transferring its properties back to the British Army.

In 1970 an extensive archaeological excavation of the site was undertaken.[58] It found evidence of a frame building on a stone foundation with cellars dating from the early nineteenth century. The foundations indicated that a number of additions were made to the structure. David McConnell in his exhaustive review of the known references to the Commandant’s Quarters[59] confirmed from military reports that indeed repairs and additions had been undertaken in 1817, 1819, and again in 1823. However, E.W. Durnford of the Royal Engineers concluded in his report of 1823 that “[t]his is a very old house to which additions have been made from time to time,”[60] which certainly suggests a much earlier origin.[61]

In 1823 the commandant moved to the more comfortable Commanding Engineer’s Quarters near the Niagara River while the more junior Commanding Engineer took up quarters periodically on the Commons. On occasion, the premises were also rented out. The first tenant in the 1830s was “Mr. Powell,”[62] who presumably was John Powell (1809–1881). John was the grandson of two influential personages: William Dummer Powell, the Chief Justice of the province, and Major General Aeneas Shaw, one time Queens Ranger and later Adjuvant General of the Provincial Staff in the War of 1812. John grew up in the home built by his father overlooking the military reserve. The property, later known as Brockamour (see chapter 21) was sold out of the family in 1836. This may have prompted John and his young family to temporarily rent the quarters on the military reserve. In late 1837, however, John was in Toronto where he became embroiled in the rebellion of 1837. He supposedly killed one of the rebels and sounded the alarm of a threatened rebel attack on the city. For his heroism he was elected Mayor of Toronto at age twenty-eight. John later returned to Niagara, became registrar of the county of Lincoln, and was commanding officer of the Number One Company, a militia unit raised in Niagara during the American Civil War.

Colonel’s Residence, 1854, artist uncertain, watercolour. This may be the commandant’s quarters on the Commons. Archaeological studies suggest the quarters may have retained elements of Russell’s original pre-war commodious dwelling. Courtesy of the Niagara Historical Society and Museum # 988.273.

A later tenant was Lewis Clement, the son of a famous father, “Ranger John” Clement who had a legendary career as a Butler’s Ranger. Carrying on the family tradition, Clement served with distinction in the militia artillery at Vrooman’s Battery during the Battle of Queenston Heights. A one-time successful merchant in Niagara, he invested in the financially troubled Niagara Harbour and Dock Company (NHDC), which may explain why he was reduced to renting premises on the Commons for several years.

With the great alarm of Mackenzie’s Rebellion in 1837, several regiments were deployed to Niagara. The new commandant appears to have taken up quarters on the Commons once again after they had been extensively renovated. A painting of the quarters in the 1850s has survived, which is the only view we have of any building on this site. While vacant it burned to the ground in 1858.

There is no visible remnant of the “commodious dwelling” on the Commons today. There is still a spring in the area seeping to the grassy surface and occasionally a groundhog digs up a piece of brick or pottery shard at the site. The natural configuration of the nearby creek bed may have been altered over the years. Otherwise, the site today probably looks remarkably as it did that August morning in 1792 when Peter Russell first came out to see Widow Murray on her farm. On an early hot summer’s morning with the heavy mist layered across the Commons, it is quite easy to conjure up the restless spirits of some of those characters who had a presence here so many years ago.