Читать книгу Riverview Hospital for Children and Youth - Richard J. Wiseman - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление[ CHAPTER 1 ]

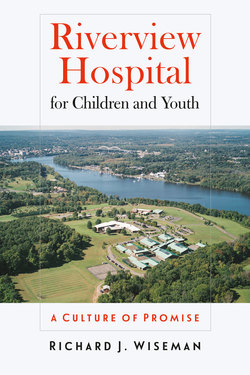

ON THE WAY UP THE HILL

…

I did not set out to write a whole book about Riverview. Originally, my intention was to write a history of the children’s mental health system in Connecticut based on my sixty years as part of that system. Having witnessed a very slow evolution that still is a long way from meeting the mental health needs of children and their families, I had titled it “On the Way Up the Hill.” The story of Riverview was contained in one chapter.

As I thought about the chapter on Riverview and my twenty years as co-director and then superintendent there, I became acutely aware of how my previous experiences in the mental health system had forged a philosophy regarding the treatment of seriously emotionally disturbed children and the function of a state hospital in the continuum of care that guided me in my vision of what Riverview should be. As I explored these paths, the chapter on Riverview turned into a book. Here you will find the story of how Riverview came to be and what it represented for children’s mental health treatment.

Let me start with a brief account of the experiences that led me to Riverview, as well as a chronology of the hospital. When I graduated from high school in 1946, I attended Drew University, Madison, New Jersey. After my freshman year, I transferred to Springfield College, Springfield, Massachusetts, majoring in group work and community organization, and was invited to join the football team. By my senior year, I realized I was eligible for another year of football, so I returned and received a graduate assistantship in guidance and personnel. There I was involved in teaching an introductory psychology course called “A Student Structured Class,” which merged the work of three contemporary psychologists: Carl Rogers’s client-centered therapy approach, Abraham Maslow’s theory of motivation and self-actualization, and Milton Rokeach’s organization of belief systems. This formed the basis of my master’s research in 1952.

In addition, I was asked to teach an orientation class for incoming freshmen. This happened to be the first year that women were admitted to the college. In my class there was a student named Eunice Ganung, and I stumbled over her name when calling the role. She came up to me to correct the pronunciation, and we became interested in each other. She became the first coed to graduate, finishing in three years, while I completed my air force commitment. When I returned we married, and within two weeks I took a job at Children’s Village, in Hartford Connecticut. I accepted a group work supervisor position, and my duties included supervising and directing a wide range of activities utilizing volunteers from the community. After a few years, my wife and I were asked to fill in as house parents in the cottage for older boys (twelve to fourteen years old). We became “parents” for a year, with twelve kids along with our own two-year-old—our boys.

One of these boys, Jimmy, was always in trouble—except in our house. He adored my wife, Eunice, and would announce to the other boys at bedtime, “I don’t want anyone to be noisy and wake up Kenny,” our son. Ours was the quietest bedtime in the village. Nevertheless, because Jimmy was always getting into (playful) trouble and annoying other staff members, a meeting was called for the purpose of discharging him. I spoke up for Jimmy, saying that he always admitted to what he had done and never blamed anyone else. I liked him. We all agreed to give him another chance. He stayed as long as possible. When he aged out, he went to a facility in Litchfield. There, he contracted appendicitis. Since he had nowhere to go to recuperate, Eunice’s parents, who had a cottage at a nearby lake, took him in. He officially became a member of our family.

Later, Jim became a successful businessman, owning his own contracting company. He married and has four children. On special occasions, Eunice and I are invited to sit at his family table. When we decided to move to a retirement facility, it was Jim, with his company van, who helped us move.

My Children’s Village experience left me with a true sense of the importance of the other twenty-two or twenty-three hours in these kids’ lives and the feeling that the fostering of children around the clock is at least as important as their one- or two-hour therapy sessions. I made the decision to invest in further training, and we left for Michigan State University, where I would pursue a doctorate in child psychology. There I had the fantastic experience of working for three years in play therapy with an autistic child and also learned the importance of individual work. But I still wanted to work with children in groups, and I was the first student in our campus psychology clinic to run a play therapy group, with four children. Also during this period our daughter, Lauren, was born, and we became foster parents to a fifteen-year-old girl who had run away from a treatment center in Texas. Sue lived with us for two years, and we thought of her as a “borrowed sister” for our son and daughter. Sue’s two children and their children continue to be part of our extended family.

When I returned to Connecticut, Ph.D. in hand, my first job was with the Connecticut Valley Hospital (CVH) Department of Psychology. That was in 1962, the very year children from other hospitals were relocated at CVH. Three years later I was asked to be director of the Connecticut Service Corps, a takeoff of the newly formed Peace Corps. During each of the next five years we hired 150 students to fill ten-week sessions. Students came from all over the world to spend time “socializing” with patients from the back wards of our four state hospitals (including the new Children’s Unit). One group went with my family and me to the woods in Danielson, Connecticut, and with the help of patients from CVH, Norwich Hospital, and Fairfield Hospital we built Camp Quinebaug.1

Every two weeks a new group of sixty patients from the hospital (adults in early summer, children in late summer) would become campers before returning to their respective hospitals to become patients again. Witnessing this transformation from patient to camper to patient was an amazing and frightening experience, one that left an indelible imprint on my thinking about the nature of hospitalization, or what I coined “patientitis.” And I wasn’t the only one who felt this way. Around a campfire one night, students were bemoaning how the campers resumed their roles as sick people upon boarding the bus for their hospitals. The students concurred that something should be done. Matt Lamstein, a student at Wesleyan University, returned to school and organized a community advisory committee with me as clinical adviser. The university gave them a house, and the group recruited student volunteers as staff. They named the place Gilead House, after a favorite campfire song, the African American spiritual “There Is a Balm in Gilead.” The house is now a million-dollar operation, called Gilead Community Services, providing aftercare patients in Middletown, Connecticut, with a wide variety of clinical services.2

After five years as director of the Service Corps and director of Camp Quinebaug, I was appointed, along with Peter Marshall, co-director of the newly formed Children’s Unit at Connecticut Valley Hospital. Peter and I realized that while some children need a secure setting, with an intensive, highly structured treatment model, we wanted our program to be as unlike a hospital as possible. Fortunately, our boss, Deputy Commissioner Charles Launi, and Commissioner Wilfred Bloomberg agreed with us. What follows are the stories of how the Riverview Children’s Unit came to be and the amazing challenges that existed for those of us who built a mental health system to serve children.

RIVERVIEW: A TIMELINE

1943–1955 Public awareness grows of plight of children with serious mental health issues, including autistic children, who at that time were considered mental health patients.

1947 House Bill 441 passes, recommending construction of a seventy-two-bed facility.

1957 High Meadows Residential Treatment Facility constructed with far fewer beds than required. Several children sixteen and under are still in Connecticut’s state adult psychiatric hospitals, referred to as “insane asylums.”

1960 Connecticut Department of Mental Health is formed.

1961–1962 Children sixteen and under are transferred to Connecticut Valley Hospital (CVH) from the three adult psychiatric hospitals. They sleep wherever beds can be found on the adult wards.

1962–1963 Children are brought together to form the Children’s Unit, boys located in Beers Hall, a section of Shew Hall, otherwise occupied by adult patients. The girls occupy an adjacent section of Weeks Hall, built in 1868.

1964 Blue ribbon committee recommends moving the Children’s Unit to a new site on the grounds of CVH.

1965 Children are moved to Merritt Hall, a newer building (built in 1960) primarily for adult women. Three wards on the top floor are allocated to children.

1966 Architect Val Carlson is hired to draw up plans for proposed Children’s Unit school on CVH grounds—on the hill overlooking the Connecticut River—with Silvermine as a central building housing a dining room, a kitchen, conference rooms, and medical records office.

1969 Letter goes to Governor John Dempsey from Children’s Unit staff pleading for recognition of inadequate staffing of Children’s Unit; co-directors Wiseman and Marshall are appointed to new Children’s Unit as an autonomous unit of CVH, with separate budget and control of programing, reporting directly to commissioner’s office; two child psychiatrists from Yale Child Study Center are assigned as consultants; development of milieu therapy concept begins as part of the change from the medical model to a residential treatment model.

1970 Children’s Unit redefines mission as a treatment service instead of a placement/referral service; adolescent program is developed in the state’s three adult hospitals. New facility at Silvermine Complex is official; recreation becomes a department.

1971 Letter goes to Hartford Courant about failure to fund new facility; funds are received and new facility opens. Dedication ceremony for the RiverView School takes place on October 8.

1971 Governor Meskill, in downsizing government, eliminates co-coordinator positions. Wiseman is director; letter from entire staff goes to governor and results in funding of new staff position for Children’s Unit.

1972 BLEU, Behavioral Learning Environment Unit, begins and behavior modification is utilized with “autistic” kids; new facility is dedicated; children move to new campus.

1973 Governor Meskill appoints commission to study which department should have responsibility for autism—co-chaired by a representative from Department of Retardation and Department of Children and Youth Services (DCYS). Wiseman represents DCYS.

1975 Senate Bill 1446 transfers all mental health programs to DCYS, including facilities; Children’s Unit becomes Riverview Hospital.

1977 Public Act 77-43, An Act Changing the Name of the Children’s Unit at Connecticut Valley Hospital to Riverview Hospital for Children, determines age limits, allowing parents the right to sign child six and under for treatment, but any child fifteen or older can self-commit. The “v” in Riverview is now uppercase: RiverView; DCYS becomes an official special school district.

1980 Riverview program starts new management structure.

1981 Riverview cottages go coed; Autistic Unit moved to round cottage, renamed Alpha.

1982 Interim management team appointed to restructure Altobello Adolescent Hospital.

1983 Riverview staff develops community services program.

1984–1985 Major renovations completed in cottages.

1986–1987 A facility for adolescents is planned on grounds of Riverview.

1988–1989 Construction begins on adolescent facility.

1989 After twenty years as co-director, then superintendent, Wiseman retires.

1990–1991 Margery Stahl becomes acting superintendent of Riverview and Altobello and is eventually appointed superintendent of combined facilities; decision made to merge adolescent facility with RiverView to become a single facility with full hospital status.

1992 Stahl retires, and Carl Sundell is appointed superintendent; regional directors announce that RiverView will be renamed Riverview Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Hospital, dropping the uppercase “V.”

1993–1997 Children and adolescent facilities are merged; administration changes four times; residential treatment center philosophy becomes that of formal hospital model; Riverview becomes an official hospital upon accreditation under hospital standards; all adolescents are transferred or admitted to Riverview Hospital for Children and Youth.

1997 After successful completion of the merger, Carl Sundell retires and Louis Ando becomes acting superintendent.

1998 Ando becomes full superintendent but given temporary assignment as bureau chief in the central office of Department of Children and Families as an additional responsibility.

1999 Robert Plant, Ph.D., appointed as superintendent when Lou Ando promoted to bureau chief of medical services in central office.

2000–2004 Focus becomes designing ABCD, a new milieu program, and implementing it in all residential units; decreasing length of stay; reducing use of mechanical restraints.

2004 Melodie Peet becomes fifth superintendent as Plant transfers to central office in charge of community system of care development (community collaboratives); this becomes a period of internal strife, poor morale, staff and kids acting out. Central office orders external program review; newspapers reflect concern; and politicians suggest closing Riverview as too costly.

2008 Melodie Peet resigns. Joyce Welch, superintendent of Connecticut Children’s Place, becomes superintendent and begins recovery efforts.

2011 Joyce retires after bringing order back to Riverview; Michelle Sarofin becomes new superintendent.

2012 Riverview retires. A new entity named the Albert J. Solnit Children’s Center with mission to be the center of children’s mental health services opens.

2014 Full description of changing mission is in progress.