Читать книгу Riverview Hospital for Children and Youth - Richard J. Wiseman - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление[ CHAPTER 2 ]

A PLACE TO START

…

In 1962 children diagnosed with serious psychiatric or behavioral difficulties were admitted to Connecticut Valley Hospital in Middletown and eventually placed in the Children’s Unit. However, it was many years earlier, in the early 1940s, that legislators, parents, mental health professionals, and scholars from the Yale Child Study Center planted the seeds for reforming children’s mental health facilities in Connecticut.

These innovators identified problems in the mental health system and began talking about the need for a residential setting for children and youth unable to be served in traditional child guidance clinics or residential child-caring facilities. A survey in 1943 by James M. Cunningham of the State Bureau of Mental Hygiene provided enough evidence to support the need for a psychiatric study home. In 1945 Governor Raymond Baldwin appointed a child home study committee that repeated the survey, focusing on the number of new cases referred to the juvenile court, State Child Welfare Division, or Council of Social Agencies in the calendar year 1945. These agencies were asked to identify children under the age of sixteen who met one of the following criteria:

(A) Required more careful observation and diagnosis than could be provided in an existing outpatient clinic if one were available. Or

(B) Required a more extended period of psychiatric treatment, excluding children diagnosed as psychotic and needing long-term care.

There were 636 children so identified, 355 in category A and 281 in Category B.

In their preliminary report to the governor dated 23 December 1946, the Subcommittee on Operations unanimously recommended that “a cottage type of institution [be] required for satisfactory work with the children,” and “the individual cottages should be small, housing no more than twelve children each.” It was agreed that the central treatment building would be planned with facilities for carrying out treatment with one hundred children in residence. The committee recommended the “immediate establishment of a seventy two bed cottage type of institution with an embracive children’s program under psychiatric direction.”1

In 1947 the first positive step in the implementation of this recommendation came in the form of House Bill 441, submitted to the Connecticut General Assembly. It was favorably received by the Committee on Welfare and Humane Institutions, but not by the Appropriations Committee, which had the responsibility of approving the $643,000 needed.

In 1948 the new governor, James McConaughy, former president of Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut, reactivated the Child Study Committee. The committee submitted its report in December 1948 to Governor Chester Bowles after McConaughy’s untimely death. Amending the original study—“inasmuch as the records of the State Hospitals indicate that approximately fifty psychotic children are admitted each year to the state hospitals, it is therefore recommended that two more twelve-bed cottages should be added to the Study Home”—seemed to be a fallback decision. The report further states, “It was hoped that the three mental hospitals might establish in one of their institutions a children’s ward with proper personnel and a program to service the approximately twenty-five psychotic children now scattered among the three institutions. Since this proposal has not proved capable of accomplishment, and since the need to provide adequately for these children remains as pressing as ever, the committee has concluded and accordingly recommends … the inclusion of these children in the Study Home.”

The subcommittee also recommended that “a psychiatric study home should not be established on the grounds of any existing institution in the state” and voted unanimously in favor of the recommendation.

The final recommendation was that “the home be planned in terms of eight twelve-bed cottages, or a total bed capacity of ninety-six,” and an additional twenty-four beds for psychotic children. The subcommittee estimated that the cost of funding this venture would be $308,198, of which $198,198 represented expenditures for personnel and the remaining $110,000 for costs of operation.2

THE CHILDREN OF CONNECTICUT VALLEY HOSPITAL

On 1 October 1953, the Connecticut Department of Mental Health with John Blasko as commissioner replaced the Joint Committee of State Mental Hospitals. Elias J. Marsh, previously with the Department of Health, Division of Mental Hygiene, and an outspoken advocate for children, succeeded Blasko in July 1957. Marsh was instrumental in moving ahead with the development of appropriate services for children residing on adult wards. He therefore ordered a full assessment of all children sixteen and under in Connecticut psychiatric hospitals. This included Norwich Hospital, Norwich; Fairfield Hills Hospital, Newtown; and Connecticut Valley Hospital, Middletown (then known as Connecticut Hospital for the Insane). His assessment showed sixty children housed on the various adult wards—eating, sleeping, and mingling with adult psychiatric patients. This meant that, on any given day in 1957, you might run into a seven-year-old autistic girl sharing a room with a sixty-seven-year-old psychotic woman.

Finally, after years of discussions, modifications, site searching, and various other delays, the State of Connecticut appropriated $250,000 to build Connecticut’s first Child Study and Treatment Home for emotionally disturbed youngsters. The result of these discussions was the building of High Meadows in Hamden, Connecticut. Unfortunately, funding was sufficient to house only a limited number of beds, many fewer than had been requested.

After a lengthy search, the state appointed Charles Leonard as the first superintendent of the newly constructed High Meadows. In a personal interview conducted on 1 May 1990, Charles shares his account of what happened:

The original plan was to have beds for sixty children, but even though the money had been approved on paper, the General Assembly only released enough for one building serving twenty children: fourteen boys and six girls. When it opened, everybody thought we would be able to take all the troublesome kids and of course that wasn’t true…. So the big questions came up about two years after High Meadows was built (about 1959 or ’60): one, how come High Meadows wasn’t taking these kids, and two, if High Meadows isn’t going to be the answer … then what about these kids in the adult wards?3

Dorothy Inglis, newly appointed chief social worker at High Meadows, interviewed each child, read every record, and performed clinical evaluations. In an article published in the Journal of Orthopsychiatry and presented at the 1957 annual meeting of the unit’s board, she and coauthor Elias J. Marsh reported the results of their study. In their summation they conclude: “Mental hospital use for children points to the need for the community to review its resources and its problems, to bring programs inherited from the past in line with the present knowledge of human behavior. We may have many worthwhile individual programs. However, they must be coordinated in a community-wide effort to meet the full range of children’s needs. Until this is done those who are not provided for may continue to be found in places never meant to serve them, such as the state mental hospital.”4

This remarkable study—as well as increased pressure from the professional community, hospital superintendents, the acting commissioner, and the legislators—led to the consideration of bringing all children under sixteen years of age to a single hospital as a demonstration project.

Exactly why Connecticut Valley Hospital was chosen is not clear, but certainly its central location was a major factor. While superintendents from each of the three hospitals—Ronald Kettle of Norwich, William F. Green of Fairfield Hills, and Harry S. Whiting of CVH—were reluctant to admit children into their hospitals, Whiting apparently accepted the responsibility.

Unfortunately, the children were not housed together; they were placed “wherever feasible throughout the hospital.”5

In September 1958, Wilfred Bloomberg was appointed commissioner of the Department of Mental Health, and the intention was to establish nineteen new positions at the proposed children’s services at CVH. When hospital administrators were unable to find a psychiatrist interested in overseeing the CVH program, Max Doverman, the former superintendent of the Children’s Welfare Center in New Haven, stepped up as coordinator. His job was tough. He had responsibility for CVH’s children, but very little authority. Children were still housed on the adult wards. The psychiatric residents on the individual wards provided the “treatment,” and Doverman was responsible for education and recreation. In 1960 a full-time psychologist, Herbert Gewirtz, was hired. Although new personnel placement continued, change occurred slowly. In his July 1960 report, Whiting wrote, “The Children’s program did not make the progress during the year that we have hoped it would. Efforts consisted largely of trying to provide better care for the children we have with a very limited staff until recently as it was predominantly a volunteer service.” He also disclosed that the children continued to be housed on the adult wards and the coordinator’s responsibility was pretty much limited to education and recreation.6

To compound matters, once the decision had been made to admit more children to CVH and word spread that a children’s program existed (albeit in its infancy), a floodgate opened. More and more children arrived at CVH. Whiting and Doverman hired eight college students to oversee evening and weekend recreation activities. This was a significant step forward because it constituted the first sustained, structured program outside of school and gave hope to the care staff that things were going to improve. Mike Karwan, the recreation director, and Louise Johnson provided clinical support. Some of the college students eventually became full-time employees. Susan Reale returned as a social worker, and Carl Sundell can be found in this history filling many roles, including superintendent. Also at this time, Sal Allessi joined the staff as a part-time clinical psychologist who provided clinical supervision to the small staff. Sal quickly became an essential teacher and supervisor, particularly in the area of group psychotherapy. But for the moment, in 1961, progress was painfully slow. In a rather clear reflection of frustration, Whiting’s report for September 1961 contains the following:

The number of children under 16 is increasing rapidly. The admission rate has exceeded the rate of progress toward development of the children’s program. There has been much misunderstanding between the hospital, the central department and the State Budget Department. As a result, we are still struggling to get positions that were granted by the legislature. There has been an alarming increase in the number of disturbed young people. Almost none of these young people are psychotic but are behavior disordered. However, the other institutions claim they cannot handle them…. The boys are a very disturbing influence, with acting out and stimulating the adult patients to do the same.7

In mid-1962, Max Doverman resigned as coordinator, and Whiting asked Herbert Gewirtz, the psychologist assigned to children’s services, if he would like the coordinator position. He accepted, but it was clear to him that the programs had to be unified and brought together in one physical area. This was contrary to the hospital’s position as stated in the Quarterly Report Ending in December 31, 1960:

We are unable by any statutory authority, to limit the number of children referred to our hospital for admission from any part of the state. Admissions flow in from general practitioners via 30-day emergency detention certificates, from child guidance clinics, from other institutions, including hospitals and correctional institutions that cannot handle these children, from the Juvenile Court and from frantic parents requesting voluntary admission. We are asked to not only treat them but to evaluate them prior to admission. This does not point to a deficiency on our part but clearly to a deficiency of the various communities of Connecticut, individually and jointly, who are neither prepared nor willing many times to accept the responsibility for the children in their midst who deserve a highly specialized kind of care. We suffer from a lack of sufficient numbers of specially trained professional staff at various levels, including senior staff, nurses and ancillary personnel.8

There were sixty boys and thirty girls in residence, an overwhelming number in view of the anticipated admission rate. In our 1995 interview, Herbert Gewirtz recalls the situation as he remembers it:

The hospital was not interested in having children. They were totally against it. It was imposed upon [the facility] by the governor’s office—they were getting a lot of pressure to provide mental health services for children. The whole thing was just dreaded by the hospital administration. Kids were trouble. They just caused a lot of grief to the administration and so they weren’t interested in them at all. So Max Doverman was operating in a vacuum because he had no power and they weren’t about to give him any. At that time it was basically lip service and window dressing and just hoping it would go away. But Max got some things started. He hired a principal and some teachers and a recreation person. Then he gave up. He had enough and left.9

When Gewirtz was appointed, he set as a priority the task of bringing the children’s programs into a unified service. This was not a popular idea. Nevertheless, he pushed forward, and eventually succeeded. He talks about the process in our interview:

The resistance to unification was tremendous. Nobody wanted to give up their domains, nor did anyone want to exert the effort to do so. The only thing that didn’t frustrate the staff was what was happening outside the hospital. People were now interested in this children’s service. Marjorie Farmer, state representative, was very vocal. Others behind it were people in the Mental Health Association; mental health professionals in various administrative positions; child guidance people who needed a place to send a kid; the Institute of Living [at Hartford Hospital]; Dr. Zeller. People started coming down to the hospital to visit, and I always presented the seamy side—never told them what was good—and that was my policy. I told them what we haven’t got and what we need. At this time I had no authority; however, when I found a vacuum I just went ahead and tried to fill it.

The first real step in unification was the assignment of the assistant superintendent of CVH as responsible for the services for children—Charles Meridith, M.D. That was really a result of all the pressure being put on Whiting (superintendent of CVH). He didn’t want to have anything to do with it so he gave it to Charlie. I developed a good relationship with him, and it was a result of the influence that I could exert on him that we thought about unification—because all we were doing was putting out fires—functioning like an occupational therapy department. So we began to move toward towards unification.10

CHILDREN’S SERVICES

In November 1962 I had my first experience with the newly formed children’s services. I started work in the Psychology Department of CVH. My training and previous experiences had been with children, and I felt I needed to get some practical experience working with adults. I decided, however, to at least take a look at this new children’s services, vowing only to look and not get involved. When I walked onto the ward in Beers Hall, I was stunned. Having just come from Michigan, where I interned in a state-of-the-art psychiatric program for children, I couldn’t believe my senses. While forty years have passed since that day and recollections fade, the dismal images that come to me are of a large room with some thirty or more beds, high ceilings, dim lighting, and creaky floors, and all I could think of was the movie The Snake Pit.11 For the moment, I kept my vow to stick with the adult unit, but I knew someday I would get involved with the children.

By this time all children under sixteen had been transferred from the other hospitals, and with a steady stream of new admissions the population of children’s services had reached fifty-five boys and twenty-eight girls. The first floor of Beers Hall was opened up to thirty-eight boys, with seventeen boys still residing on the adult wards. Soon thereafter, the girls were moved into adjacent housing in Dix Hall.

In a River Views interview, children’s services worker Andrea Spaulding recounts, “Things were very chaotic, every patient seemed to exhibit a different problem behavior or psychosis. All you tried to do was keep them in order.”12

The Hartford Courant, in a series of articles about the plight of children in Connecticut hospitals, aroused public outcry when it revealed the use of straitjackets on children.13 This naturally caused a political furor, and the commissioner of the Department of Mental Health ordered an internal investigation. Charles Leonard, who had vast experience in conducting surveys of children’s facilities, volunteered to do a survey if he could do it his way, which was to live on the grounds and be granted free run of the place, both day and night, for a period of one week. The commissioner agreed to ask CVH superintendent Harry Whiting. Harry graciously agreed to Charles’s stipulations and made arrangements for him to stay in a guesthouse. Leonard spent the days and several nights on and off the wards and described meeting “some real good, down-to-earth, competent psychiatric aides at two and three in the morning,” but the Beers Hall facility was an “awful, awful, terrible place—even the toilets were awful, stinky.”14

Another major step in the unification of the children’s programs was the assignment of psychiatric residents. According to Gewirtz, “Previously … kids on different wards … were assigned to whoever worked on that ward. Each ward had its own personnel. Now residents were responsible to me—not for clinical supervision but more administrative, general strategies around kids. This was historically a first for psychiatrists to come under a non-physician.”15

Fragmentation had been true in all other disciplines—significantly nursing, which, of course, included all nurses and psychiatric aides. Nursing the hospital’s largest department. The hospital structure included a nurse supervisor for males and one for females, each reporting to a director of nursing. In order to add a nurse supervisor for children’s services, Gewirtz established a new position, director of group living, reporting directly to him as director of the Children’s Unit. With this new title, Louise Nelson had more direct responsibility to children’s services and its administration. She therefore became a pivotal person in the program. Also, John Thomas, the medical director of High Meadows, in Hamden, became a consultant. This added to the political pressure for unification of child services. Gewirtz explains:

It had political implications because everyone was looking to see what was going on. It was very shaky yet. At that point, Lou Perlman completed his residency and came on to help run the children’s services. He started as co-director. There were a lot of problems, however. I thought it could work out because we were good friends. I was looking forward to his coming. We handled it by splitting our domains. Lou had the clinical side and the ward, and I took the outside work (administrative, politicking, etc.). It didn’t work out. Lou became appointed director, and I became assistant director. There were a couple of reasons for that. One had to do with a letter I sent to a doctor in New York…. The guy was a big name in the field who talked to Bloomberg [then commissioner of mental health], who called Dr. Whiting, and people were very upset with me. Bloomberg went on to say, “I think we need a medical person there,” so I left, primarily because of that. The idea of co-directors was too problematic. Factions developed; there were too many process struggles. It turned out that Lou Perlman didn’t stay long either. I think he didn’t really want the administrative responsibilities.16

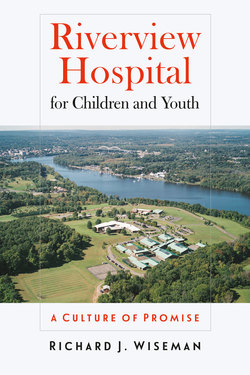

The original planning for the construction of the new Children’s Unit began in the early 1960s, soon after the children moved to CVH. Charles Leonard remembers driving out to the site of the Silvermine Building. Sydney Finkelstein, a member of the hospital’s advisory board, accompanied Leonard. They were sitting on the hillside and looking over the Connecticut River and Middletown hills when Charles said to himself, “This is it, envisioning a beautiful setting for a residential treatment center.”17

And so on 25 April 1963, a report entitled “Proposed Future Hospital Recommendations for Children’s Services” was finalized. It documents the plan:

We wish to move as rapidly as possible towards the establishment of an integrated Children’s Residential Treatment Program under one roof. This would allow children to be evaluated, treated and cared for in the setting of the program designed specifically to meet their needs and carried out by the same professional staff at all levels. It is our opinion that a physically separate children’s center or section removed from the main stream of the adult therapeutic units is necessary for a well rounded, effective and adequate functioning children’s program in all respects.18

By the end of 1963, administrative integration had been accomplished for girls and boys. Louise Nelson acted as nurse supervisor, and eight new employees were on board. The Children’s Unit was finally a separate service, and the new Connecticut Valley School had been opened. The superintendent’s report for that year quips, “The children celebrated the opening of the school by setting off the fire alarm six minutes after the formal opening, much to everyone’s consternation.”19

Oh, well! School commenced with some seventy children attending.

THE NEW CHILDREN’S UNIT (TEMPORARY) SCHOOL

In 1962, when children were first brought together at Connecticut Valley Hospital, planners envisioned and built a separate one-story school building.

Thirteen teachers were hired, including part-time physical education teacher Eunice Wiseman and a full-time physical education teacher, Jack O’Day. Eunice describes her experience:

I started at the Children’s Unit in 1962 as a part-time physical education teacher. I was told I could take the children each day to either the gym or to the pool. Or I could do whatever I wanted with them. Sometimes I would go and get the children and they wouldn’t be ready. The staff would be playing cards, and I would have to round up the kids and get their stuff and take them to the gym or the pool. Then there was a skating rink and once a week I took them there. One day Jack said, “This is your day to take the van.”

I said, “The van?”

“Yes, the van. You can take the kids wherever you want to take them.”

So I started field trips—to the farm, to the bakery, to different places—so we could make interesting experiences. I told the kids when they got in the van, “You better be good because I have to drive and I don’t want any distractions.” They were always good for me.

One of the things I accomplished working there was to convince the superintendent that the kids should be drinking milk. The adults had milk but the children did not. So I went to the superintendent’s office and I told him the children should be getting a pint of milk each day. Finally they agreed with me and so the children started getting milk.

The children were not supervised well. I had children that were bigger than I was that had grand mal seizures. One day one of the girls had a seizure on the steps into the pool. Had we been in the pool, I was not told how I could deal with the child. Fortunately, it was on the steps and I called and they sent an ambulance.20

Eventually they hired a principal, Irving Renn, and a few more teachers. Two of those teachers, Betty Flynn, a math teacher, and Willie Fuqua, a music teacher, both fresh out of school, were hired on the same day in the early 1960s (and both retired on the same day in the late ’90s). Until the school was built, teaching took place either on the ward or in small rooms.

Robert Miller, chief of professional services of CVH, was hopeful in his year-end report: “[D]uring the coming quarter, we believe that our efforts should be directed toward unification of the service administratively with the goal of integrative planning.”21

In 1964 Suzanne Peplow, a social worker, became co-director with Lou Perlman. Lou assumed the clinical responsibilities and Suzanne took over the managerial/administrative duties. This collaboration lasted for a short time. Lou resigned to take a position elsewhere, and Robert Miller assumed Perlman’s duties in addition to his own. Joyce Aksu was appointed supervisor of group living, replacing Louise Nelson.

Marcia Pease-Grant started as an intern at CVH and later became social work supervisor—a role she held until her retirement in 1995. Marcia tells about her early days at the Children’s Unit:

June 1964: I was hired by the State of Connecticut for $6,000 a year and worked mainly on the Children’s Unit at CVH. The ’60s were a time of political stability under Governor Dempsey and the Democrats. Human services were in vogue, and social workers were in demand. The boys’ ward was in Beers Hall, the girls’ ward was in Dix Hall, and the staff offices were in Shew Hall. These buildings were very old and dark even then, and were condemned within a few years. There were forty boys on one locked ward, their gray metal beds alternating with gray metal cabinets, lined in neat rows in one very large room. The outside wall was covered with large windows, but had thick safety screens, which kept out the light. There was a television room and a large screened sunporch, like a cage, on the second floor of the building. There was one large bathroom with exposed pipes, and one boy burned his back rather badly when he accidently leaned against a pipe. The dining room was in Paige Hall. It was huge, and served many of the chronic adult patients. It was very noisy. Worst of all the boys had to walk to it through a second-story walkway, which had wooden sides, but the roof was wire mesh and there was pigeon shit everywhere. Years later I watched this building and walkway demolished, and I cried with joy at the sight.

The school and recreation areas were equally in poor shape; the floors literally undulated from room to room. Overall the girls’ ward was in better, brighter condition, having light beige walls and cleaner windows, bedrooms for three or four girls, a more modern, sanitary bathroom, and access to the outdoors, being on the ground floor. There were usually about twenty-five girls at any one time. The girls’ ward was more violent than the boys’ ward, and at times I was physically afraid of both the girls and the staff. These children, all crowded together, ranged in age from four to sixteen, and ranged diagnostically from autism to schizophrenia to conduct disorder to sociopath to traumatized to simply in no need of hospitalization at all.22

In 1964 a blue ribbon committee recommended that the children’s services be moved to the Silvermine Building. In that same year, the state appropriated $1,000,000 to begin construction of a children’s ward.