Читать книгу In the Name of the Son - Richard O'Rawe - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThree

Gerry Conlon was astute enough to know that American political influence casts a long shadow and that sometimes that shadow engulfed 10 Downing Street. He also knew that, as a miscarriage of justice victim, he was in a unique position to exhort American politicians to persuade the British government that it was not in their vested interest to continue to deny justice to the Birmingham Six. So, in early March 1990, along with his trusted cousin Martin Loughran, Conlon returned to Washington to attend the Congressional Human Rights Caucus hearing on the Birmingham Six case, which Congressman Tom Lantos had promised he would convene during the Irishmen’s previous trip. The hearing was co-sponsored by Congressman Joe Kennedy of the Ad Hoc Congressional Committee on Irish Affairs.

There were high expectations of a successful outcome to the caucus hearing, not least because Conlon had a masterful grasp of his brief and had the ability to deliver a faultless presentation. More than any other facet, it was his personality that made him a reliable persuader: in temperament, he was a composite of nervous energy and cordiality; in conversation he had the gift of giving the speaker his undivided attention; in practice, he was blessed with a prodigious memory, which meant that he could remember dates, places and people’s names, even if he had not seen those people for a while, sometimes for years. This meant that if he had been introduced to a politician in the past, or his wife, or his kids, he remembered their names and details. This was impressive data storage, which did not go unnoticed by almost everyone with whom he came into contact.

Once again Conlon availed of Sandy Boyer’s services to help co-ordinate his activities. Even before Conlon had left for the United States, Boyer, an unsung hero of the Birmingham Six narrative, had been busy sorting out the Irishman’s agenda: ‘In the week or so before the hearing, I was speaking to Joe Kennedy’s staffer regularly. We were going over the schedule for the hearing and I was able to answer questions about the case.’1 The significance of Boyer’s contribution cannot be underestimated because, as a result of his discussions with Kennedy’s staffer, a briefing document for members of the caucus was produced, which said: ‘Their [the Birmingham Six] convictions were based upon signed confessions and forensic tests which indicated that the defendants may have been severely beaten at the time the confessions were obtained. Furthermore, the forensic tests were shown to be incomplete and unreliable.’2

Boyer had meticulously prepared the ground, and now it was time for the Guildford Four man to deliver. Boyer recalls:

Gerry and I met in Washington two days before the hearing. We went to talk to the Kennedy staff member who was organising the hearing. She wanted us to meet Joe Kennedy the next day and started to tell us that they had a new office. When, rather than her telling me where the new office was, I told her, Gerry gave me a big wink. The point isn’t that I had done anything especially brilliant, but that Gerry, without even thinking about it, was sending me a compliment, just between the two of us. Little things like that made it such a pleasure to work with him.3

Sandy Boyer recollects that when the caucus convened on 12 March 1990, Joe Kennedy’s staffer was buoyed up because there were more members of the US Congress in attendance than there were staffers. As well as Conlon, the caucus was addressed by Gareth Peirce; the Catholic Primate of All-Ireland, Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich; human rights advocate and barrister Lord Tony Gifford QC and Seamus Mallon, the Social Democratic and Labour Party MP for Newry and Armagh. Mallon made it clear that it had been the IRA, not the Birmingham Six, who had carried out the bombings.

If knots were tightening in Conlon’s stomach as he waited to address the congressmen, he did not show it. Neither did he show any concern about the fact that he had no prepared notes to refresh his memory – his memory did not need refreshing. Sandy Boyer recalled: ‘Gerry was the star. In his testimony he said, “I know what happened to the Birmingham Six because the same thing happened to me. I was held for six days in four police stations without food or sleep. I was beaten, humiliated, degraded and stripped naked. At the end of six days I signed a confession. I was never allowed to see a solicitor.”’4

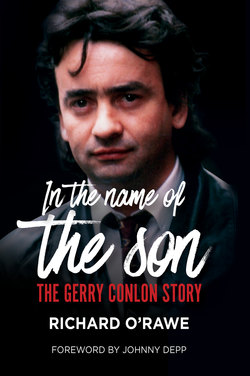

As it turned out, many praised Conlon’s presentation. Congressman Joe Kennedy said: ‘It’s one thing to hear all the very sound legal arguments put forward by Tony Gifford, but nothing compares to hearing Gerry Conlon. It certainly left an indelible imprint on my mind.’5 Colman McCarthy, a member of the Washington Post Writers Pool, later wrote: ‘Gerry Conlon, with unclipped coal-black hair, dark mournful eyes, and a wrinkled suit, had the look of a villager in one of Ireland’s wild moors. He might well have been in one today – farming, raising a family – had the British government not imprisoned him for 15 years as one of the Guildford Four.’6

In his concluding remarks to the caucus, Congressman Chairman Tom Lantos said: ‘It is clear in this instance that British justice has failed, and we will pursue this matter to its end.’ Thanks to Gerry Conlon, Sandy Boyer, and others – Amnesty International in particular – the long shadow of American political influence once again engulfed 10 Downing Street, and it could not be ignored.

For Gerry Conlon it was time to take off that wrinkled suit and hit the bright lights of the Big Apple, where he stayed with friends in the Floral Park neighbourhood of Queens. At the Limelight nightclub in downtown New York, a young Irish girl called Ann McPhee introduced herself to Conlon and said that she was nanny to the Irish actor Gabriel Byrne’s children. She told him that Gabriel was handing out Gerry’s book to everyone who visited him, encouraging them to read it. It was through Shane Doyle, Gerry’s friend and owner of Sin-é Café in Saint Mark’s Place, that a meeting was arranged with Gabriel Byrne.

Gerry found Gabriel impressive: ‘Gabriel Byrne called. He said he’d read the book and loved it and thought it had the potential to make a great film.’7 After their discussion, Gerry decided that Gabriel was the man who could get his film produced. However, with no screenplay, no definitive outline, no money, and nothing more than a wildcat idea, the two men shook hands and concluded a gentleman’s agreement for a nominal figure of one dollar, which gave Byrne the option to develop a film based on Conlon’s life.

On 26 March 1990, RTÉ, the Irish broadcasting company, screened Dear Sarah, a £1 million television drama based on letters written by Giuseppe Conlon to his wife Sarah while he was in prison. The drama, written by Irish journalist Tom McGurk, told the story of how Sarah had visited Giuseppe for the first time, and of how they had to sit at opposite ends of a glass screen, unable to even touch hands. It also showed Sarah Conlon’s immense courage and fortitude, as she fought, almost alone, to clear her husband’s and son’s names, and of how she coped with the strain of travelling between Belfast and Britain to visit her dying husband.

Giving a background analysis to Irish News reporter Pete Silverton, McGurk said: ‘Sarah had an invalid husband and a son she spoiled stupid, and one day a steamroller hit her.’ Silverton pointed an accusing finger at Gerry Conlon for the trouble that had befallen the Conlon and Maguire families:

The steamroller made two passes over Sarah, of course. First her son was arrested – drinker, druggie, gambler, layabout, petty criminal. Like the rest of the Guildford Four, you couldn’t have relied on him to burgle the local chippie, let alone organise a pub bombing. Then his ‘confession’ – naming the Maguires – led directly to his own father’s arrest. Would it be any wonder if the Maguire family refused even to speak to Gerry again? Of all his relatives, they must have thought, why did he pick on us? What did we ever do to him?8

Had Conlon been in an uncharitable mood, he might well have returned the question to Silverton: ‘What did I ever do to you?’

Speaking of Dear Sarah, Ann McKernan said: ‘There were dramatic moments in the film … my father being trailed up the stairs in the prison when he wasn’t able to walk, my mother’s letters being taken from him. These things they did to my father because they couldn’t beat him as he was a sick man.’

Commenting on the drama, RTÉ executive producer Joe Mulholland said, ‘It is a haunting and disturbing true story of a bewildered and ailing man caught up in an implacable system. But it is, moreover, a love story of two people whose faith in each other never wavered.’9

Proved Innocent was launched in Buswells Hotel in Dublin on 11 June 1990, and later that night in the Palace of Westminster. The book is an earthy story of the author’s upbringing in a strictly Catholic home in Belfast’s Lower Falls, where the rosary was recited every night and all family members had to attend. Conlon relates how he looked on this period of his life as a happy and carefree time, even though money and luxuries were scarce. He goes on to narrate how, after leaving school, he pursued a career as a petty criminal and shoplifter, and of how he got the boat to England to escape the violent conflict that was engulfing Northern Ireland. Fast-moving, sometimes hilarious, always fascinating, Conlon was like a gondolier on Venice’s Grand Canal, as he navigated his readers through the crowded, choppy waters of his life. The book became an instant bestseller. When asked what he hoped to achieve by publishing Proved Innocent, Conlon said: ‘There is no one person whom I would like to single out for retribution. That and revenge is something that I do not want. All I am hoping to achieve with my book is to point out that sometimes the British justice system does fail. The British don’t have sole copyright on injustice.’10

At the Dublin book launch, Conlon called on the IRA to call off its armed campaign in order to get all the Irish prisoners in English prisons released. In Belfast, on 13 June, hundreds of people formed queues in the street outside Waterstones bookshop and a mighty cheer went up when Conlon appeared. Inside, he signed book after book, inscribing each with a personal message. In a newspaper interview, given on the same day, he once again committed himself to campaigning for the Birmingham Six, saying: ‘I couldn’t live with myself if I walked away. I would do anything or go anywhere to help them.’11 He also revealed that he was ‘living out of a suitcase; my time is not my own. I don’t see enough of my family.’12

On his return to London, Conlon had barely time to unpack his bags before he was getting on another plane, this time to Copenhagen, with other Birmingham Six campaigners, to lobby representatives at a conference for Security and Co-operation in Europe. Twenty-three out of twenty-eight European and North American countries had sent delegations to the Danish capital. While Conlon could not, and did not, claim credit for convincing the delegates to pass a vote calling on the British government to re-examine the convictions of the Birmingham Six, his participation was nevertheless telling: ‘Gerry’s contribution was crucial,’ wrote Paul May, who chaired the London-based campaign to free the Birmingham Six. ‘Gerry described powerfully how it felt to be brutalised and imprisoned as an innocent man.’13

In between campaigning for the Birmingham Six at home and abroad, Conlon was contractually bound to promote his book in different cities around the United Kingdom and Ireland, while also trying to get a film of his book produced. At the same time, he was struggling to rebuild relationships with his family. The sad reality was that the Conlon family, particularly Gerry, had had to insulate themselves from the world in order to survive their ordeal: they had all been prisoners and each of them was deeply affected by the traumatic events that had been visited upon them. If that was not enough, Gerry had to somehow find a way to temper the guilt that haunted him over the death of his father in prison. Siobhan MacGowan, the sister of The Pogues vocalist Shane MacGowan, met Conlon soon after his release and became a close friend and confidante for the rest of his life. She shared her experience:

Gerry was really deep. We would’ve talked about all sorts of things – his family when he came out and how he couldn’t look them in the eyes because he felt so guilty. He was really soft. That’s why he kept away from Belfast for so long; he couldn’t get past it. He wanted to go home but he couldn’t. And especially his mother – when he looked her in the eye. He was emotionally wounded.14

The extent of this emotional wounding was made apparent in a report compiled by Barry Walle, a counsellor and psychotherapist, to whom Conlon had been referred by senior house officer Dr Joanna Bromley and consultant psychiatrist Dr Geoff Tomlinson in 2000:

Gerry can be described as split: three parts adapted to prison, one part outside. His internal world is almost entirely taken up by vivid and detailed ‘memories’ of his arrest, interrogation/torture, conviction, and prison, so vivid that he is, in effect, reliving it. It is his reality for most of the time without the benefit of the support and companionship of fellow prisoners. Gerry’s behaviour is further confused and complicated because there are no real walls. He often wishes he was back in there because then the way he feels would make sense; he would fit.15

Conlon’s external world was almost as confused, convoluted and perhaps as frightening as his internal one. He had to adjust to a society in which he was viewed as both a lion and a jackal:

My trouble now is that half the people I meet think I’m some sort of hero, which I’m not, and the other half think I’m a terrorist, which I never was. I go to pubs and clubs, and in lavatories everyone wants to shake my hands, and I don’t know where their hands have been. I went to Glasgow for a Celtic-Rangers match and people I never knew were taking off their wedding rings and giving them to me.16

To complicate matters, the Guildford Four were still the targets of attacks from the British judiciary. In a pre-retirement BBC television interview, the Recorder of London and the Old Bailey’s most senior judge, Sir James Miskin QC – the same judge who had said that the release of the Guildford Four was ‘mad’ – offered the ludicrous theory that the IRA could have bribed some young and hard-up policeman to ‘cook up’ certain documents to help free the Guildford Four. It mattered little to Sir James that, other than within the confines of his fertile imagination, there was no evidence of the existence of any such young and hard-up policeman. The possibility was there, and presumably, that would have been enough for him, had he been on the bench of the appeal court on 19 October 1989, to send the Guildford Four back to prison. The same man was no stranger to controversy: at a speech at a Mansion House dinner in London in March 1988, he told a ‘joke’ about ‘nig-nogs’ and said that he was engaged in a trial against ‘murderous Sikhs’ (one of whom he later sentenced to 30 years’ imprisonment for murder).

A barrister, and Fianna Fáil member of the Irish parliament, David Andrews, said of Sir James’s comments that he was ‘very concerned that a mind like that can preside over a judicial system in any democracy. I feel a great sense of relief that Sir James is no longer in a position to adjudge cases.’ Andrews went on to say that the comments were ‘so right wing as to be almost fascist.’17 Gerry Conlon said that the judge’s critique was part of an ongoing ‘whispering campaign’ by the British judiciary against the Guildford Four. ‘This has put our safety in jeopardy,’ Conlon said. ‘I would think that any kind of crazy character in this country could believe what Sir James Miskin has said, and, therefore, want to attack us, physically.’18 Arguably, it was not in Sir James’s nature to apologise for anything – certainly not to anyone he perceived to be an Irish terrorist – and he unwisely refused to express regret for his outlandish remarks. But nature and wisdom sometimes make incompatible bedfellows and, as the eminent eighteenth-century Irish parliamentarian, Edmund Burke, once put it, ‘Never, no never, did nature say one thing and wisdom say another.’19

Despite the high-velocity pace of his life, Gerry Conlon did his best to enjoy his freedom. He was not shy and never lacked the confidence to walk up to a woman and strike up a conversation, with the intention of bringing her home to his bed. Nor was he one of those crusading bores who talked about nothing but the good causes that consumed his daily existence. When he was not ‘working’, he embraced life with the passion of one who felt that he had been denied it for too long. One of his many girlfriends was Dublin journalist Fiona Looney. She first met him six months after he was released from prison, though she didn’t get to know him until a year later. She remembers that Gerry and Paul Hill were ‘quite the rock stars’ in Dublin in the months following their release.

I think I first met him in The Pink Elephant nightclub in Dublin after an RTÉ Late, Late Show, but I really just shook his hand and wished him well. For what it’s worth, I thought he was as sexy as fuck! I had known Marion, Shane, Vicky, Siobhan, Louise Neville, and all The Pogues crowd for a few years, and I met Gerry through them. I spent some time with him over the course of a few months, but I wouldn’t describe our relationship as a romance. He was a charmer, but there was also an innocence about him which I found really touching. When I knew him, he was incredibly forgiving and lacking in bitterness over what had happened to him. I was amazed at that – he honestly didn’t seem to bear anyone ill will. On the other hand, he was like a child in a candy shop – and he helped himself to an awful lot of candy. He slept with dozens of women in the first couple of years after he was released and, like an adolescent teenager, he kept count. I think the count was around one hundred and fifty-six, and he was hoping I’d be the one hundred and fifty-seventh. Most women would be offended by that, but I thought it was funny and endearing. I remember him telling me how grateful he was to the IRA for taking him under their wing in prison; he reckoned it was the only thing that prevented him from being raped.20

Conlon started smoking marijuana at the age of sixteen and had sustained the habit in and out of prison. Occasionally he snorted cocaine and took ecstasy tablets, usually at a party or a rock concert. Frank Murray, the manager of The Pogues, has vivid memories of himself and Conlon hanging around together in Camden Town at the start of 1990: ‘He was full-on, you know? Anything that he couldn’t do in there [in prison], he was trying to do out here; he was trying to live the sixties, the seventies, and the eighties, all in one month. As a friend, it was very hard to go to Gerry and say, “Look, I think you’re overdoing it a bit” because he’d been in jail for fifteen years and he felt he had the right and it was like, “Nobody’s gonna tell me what to do.”’21

On 29 August 1990, Kenneth Baker, the British Home Secretary, referred the Birmingham Six case back to the appeal court, on the basis of further fresh evidence becoming available. In this instance, the fresh evidence was of a forensic nature, which called into question the veracity of tests carried out by Home Office forensic scientist Dr Frank Skuse, whose original examinations indicated that, when arrested, four of the six prisoners had nitroglycerine on their clothing. It was the end of an era for Gerry and all those who had campaigned for this day. It was a victory, but even in victory there sometimes lurks the aura of defeat. At a stroke, gone was the raison d’être for Conlon’s post-prison existence. The campaign was over, at least until the appeal was heard. What to do?

Tens of thousands of pounds in compensation was being sent to Conlon by the British government, and he spent it as if there was no tomorrow. The working-class lad from Belfast now had enough money to indulge practically any flight of fancy that engaged his imagination: an idyllic situation, many would say, but, for the emotionally disturbed Conlon, being given a pot of gold was the equivalent of an alcoholic being handed the keys of a bar and being told to lock the doors behind him on his way home.

Cut adrift from the cause that had consumed his life since he had come out of prison, Conlon now had time to seek a fair wind, and on his journey he found plenty of fair-weather friends. He wanted to fit in, to claw back those lost years, to be ‘like the same fella I was when I went in’. He frequented Irish bars, chased women and generally tried his best to have a good time in the company of lads who reminded him of his own youth.

It was an impossible situation. For a start, I had money and they were all on the sites or else on the dole, and I felt guilty as hell about that. I’d buy everything, all the drink, all the meals; the lot. It got to the point where I needed the hangers-on because I just didn’t like being on my own. But, the strange thing is, I didn’t regard them as hangers-on because I didn’t feel I was deserving of anything more than they had. The only way to deal with that was to give the money away.22

He brought his friends to Manchester United and to Glasgow Celtic football matches, where he would have spent thousands of pounds on drink and drugs. He also brought some friends on holidays to Mexico, Jamaica, and other exotic locations and again footed the bill. Paddy Armstrong and he took a holiday in Goa, in western India.

One who was not a hanger-on but who was amongst the most prominent people in Conlon’s life in the early years after his release was Joey Cashman – a Dubliner and the tour manager of The Pogues. In September 2015, sitting in an alcove of the Marine Hotel in Dublin’s northside, Cashman raises his glass of vodka and Red Bull and says: ‘To Gerry Conlon – the bollocks!’ The glass does not reach his lips before an irreverent laugh erupts from him. Cashman has long grey hair that flaps over his left eye, a goatee beard, and he is dressed entirely in black, with winkle-picker shoes. ‘I loved the guy,’ he says. ‘Me and him, man, we were best buddies; if I were to tell the stories … I’m off seven drugs, you know: crack, heroin, ordinary coke, weed, uppers, downers – hey, I’m even off nicotine. Got there all on my own. When I go to the clinic, I insist they take a sample every week.’

Cashman brushes the hair away from his left eye, looks around and turns back. ‘Do you think he’s listening in?’

‘Who?’

‘Gerry.’

‘Course he is!’

‘Hey, Gerry-man! You’re still a bollocks!’ Cashman bursts into another fit of unfettered laughter. He is clearly enjoying reminiscing about his buddy. ‘I think, I can’t be sure, but I think I met Gerry for the first time backstage at The Palladium in New York on the day before Saint Paddy’s Day 1990, but I’d only time to shake hands with him and leave it at that.’ Later they met in a pub in London and afterwards went back to Cashman’s house off the Prince of Wales Road in Camden, where they traded stories all night. Cashman smiles when he talks about his friend from Belfast:

We might have had a line or two of coke, but we didn’t need it; we were both speedy people anyway. And me and Gerry, we clicked on so many levels, and then we became totally inseparable, so even when we were at different meetings, we’d still ring up during the day and make arrangements to go out that night. And if I could’ve talked for Ireland, he could’ve talked for the United Nations. But we’d some great laughs that night in my gaff. There was this one story that he thought was particularly funny.23

Joey explained that The Pogues had started working on their third album, If I Should Fall from Grace with God, in May 1977, and one of the tracks on the album was ‘Streets of Sorrow/Birmingham Six’, written by Terry Woods and Shane MacGowan. The idea for the song had come from Frank Murray, during a conversation with Shane MacGowan, and it was banned by the Independent Broadcasting Authority in April 1988 because it contained ‘lyrics alleging that some convicted terrorists are not guilty and that Irish people in general are at a disadvantage in British courts of law.’ Commenting on the ban, Murray said: ‘The Pogues will continue to write about what they want and we hope every other artist does the same.’ For MacGowan it was a challenge that he was more than willing to take on: ‘Banned for what? It’s straightforward police state repression of freedom of speech and its censorship.’ For the free-spirited Pogues, the ban had to be defied.

On 12 November 1987, The Pogues were playing Queen’s University in Belfast. Joey Cashman recalls:

For some reason, Frank Murray wasn’t with us, so I’m standing in for him. Anyway, I’m in my hotel room and I get a phone call, and a very stern voice says, ‘Are you the manager of The Pogues?’