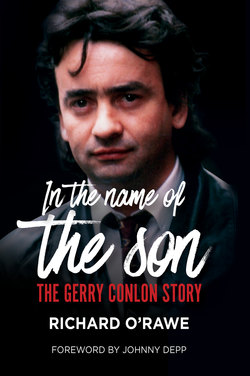

Читать книгу In the Name of the Son - Richard O'Rawe - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеUpon Thinking of My Long-Lost

Brother, Gerry …

20.8.17

I first met Gerry Conlon, by absolute chance, in the hallway of a talent agency in Los Angeles, somewhere around 1990, I believe. It was a rare occurrence for me to visit the place, which made the moment with Gerry all the more charmed.

I had pressed the button and was en route to my destination floor. Upon arriving, the doors opened. As I exited, I spooked a couple of guys to my left, who looked, as did I, sorely out of place. The guts of this heinous, monolithic terrarium of steel, glass and dubious “art”, sparsely shaming those ghastly “modern” walls, was not a typical setting for folk such as myself, or gents of this breed, who, in my personal and moderately professional estimation, were satisfactorily saturated and teetering along the same invisible ledge, as though they’d been out on the prowl, for an especially impressive stretch. Indeed, they looked just like the depraved, miscreant, unhinged maniacs I always tended to hang out with. One of them possessed the squinty scrutinising eyes of the streets, and was as skinny as a dried lizard. He also seemed to have been divined with a prevailing lack of residents in the tooth department. The questionable few choppers that had not been evicted, were lonely, jagged and rotting. His stringy, straight hair – greasy to his shoulders. This was Joey Cashman. A hilariously clever and quick-witted Irishman, from just outside Dublin. He was the manager of one of my favourite humans of all time, the infamously tattered genius of lyric and song, Shane MacGowan, from the Pogues. Joey was a lovely man, who held strong to those he loved. Devoted and solid. I would later survive many adventures with this man, and to this very day, I have been informed of Joey’s tragic and “sudden” demise, and miraculous resurrection, at least fourteen times. The other fella was from heavier stock. He laid a big, beautiful, slightly crazed Cheshire Cat smile on me, which showed that this man had at least met a dentist once in his life. But it was his eyes that got me. Eyes that simultaneously exuded wisdom and a childlike purity; a desire to live and love. There was no question that these powerful eyes had seen and experienced much. This was Gerry Conlon. He approached me and introduced himself and his mate Joey, with the exuberance of a man who held nothing back. He gave of himself freely. His eyes sparkled like ten thousand stars had just given birth to ten thousand more …

Gerry Conlon had first gotten my attention when he stomped out of the Old Bailey in London in October 1989, fists raised high and declared to the world that he was an innocent man who had spent fifteen years in jail. The authorities had tried to shove him out the back door, in order to avoid the inevitable media frenzy, but he had refused, instead imparting something along the lines of “Fuck you, I’m a free man, youse fuckin brought me in the back door, I’m going out the front!” My curiosity had then been further fired when I’d learnt that he’d witnessed his father, Giuseppe, another innocent man, die in a British prison. And now here he was, Gerry himself, stood right before me, in this, the most incongruous of places possible. Fortunately, to prevent matters from being overtly one-sided, he recognized me from something or other and lunch was duly arranged.

Gerry was altogether an articulate, personable, funny, self-deprecating and fierce humanitarian. He was an absolute gentleman, who possessed all the knowledge of law in the streets of Belfast. Chivalrous, loyal and highly sensitive to any injustice, no matter how large, or minute. If he loved you, you were blessed to be invited into his circle, where there existed no edits with him. Gerry said what he felt and meant what he said. He had no difficulty in getting his point across. Ever. He had grown so used to having his prison clique around him that those of us who spent significant amounts of time with him became a newfangled version of just that. He was a 100% trusted friend and brother, to the very end.

During lunch, he broached the subject of my playing him in the film that was to be produced about his life during his unfathomably unjust arrest and incarceration. More than touched at this profoundly personal invitation from this man, I was already on the deck wiping away tears (as was he), when he gave me the first details of his abduction and torture by the British authorities. During this, our first proper encounter, he spoke more of his experiences in prison. Despite the hardship that had been visited on him, I came away with the impression that here was a character whose passion for life had been in no way diminished. He was starving for it. As much as he could get ahold of.

Later, during the summer of 1991, I found myself fortunate enough to be invited on holiday with Gerry and his family. Despite being more of a grape man, the only flavours I recall from that trip are Black Bush, Jameson’s, Irish Coffee and of course, the Guinness. The Conlons were lovely people, one and all, but I had a special place in my heart for Gerry’s mother, Sarah, and his sister, Ann. These were sweet, strong and kind folk whose lives had been torn asunder and putting them back together wasn’t going to be easy. But, if my experiences with these wonderful people told me anything, it was that their humour remained perfectly intact. In fact, I specifically remember some sloppy conversation with both Gerry and I employing words and sentences that our mouths were shamefully unfit to speak, as our eyes began to see double. At some point Gerry decided that we must go to Dingle to see Fungie, the dolphin. Very important. Gerry had no need to convince me, of course I was going to say yes. Who wouldn’t want to go to a place called Dingle to see a dolphin named Fungie? Gerry proceeded to inform me that his cousin, David, would be coming down that night to Dublin from Belfast, and would drive us to Dingle in the morning. And indeed, as promised, later that evening, David appeared in the door of the bar, screaming, “Gerry, ya fucken cunt!” I turned to see a big, thick and angry-looking brute, with ginger hair and pincers for arms. We were introduced. I shook one of his metallic claws and looked him squarely in the eye. “It’s a pleasure to meet you,” I said. He replied with what may have been an eleven-syllable fuck-off. I still don’t know. The man was utterly pickled. If worry was going to come into the picture it would have done so at exactly that moment. We sat down to have a drink. And drink we did. What seemed like an instant later, it was brought to our attention that we were fast approaching 8.30 a.m. It was time to go. Worry never seemed to enter the picture. We had merely forgotten to sleep. But, whilst not feeling all that bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, we remained determined to make our rendezvous with this mysterious dolphin called Fungie. Fungus. I felt like fungus. Gerry looked like fungus, and David was immune to fungus. Of course, I was chosen to ride in the front seat with David. His co-pilot, as it were. It is potentially the only time I have put a seatbelt on without hesitation. Or actually thought about one for that matter. But David, it turns out, was a fantastic driver. His claws were quite handy for storing pints of Guinness, but it didn’t matter, because his feet were steering. So, as I also clutched two pints of Guinness, similar to Gerry in the back seat, I thought that if we were to die, it would be the most interesting trio of obituaries. Anyways, we soldiered onward towards Dingle, but at some point there came the inevitable need to replenish our glasses. The next road sign informed us that Limerick, also known as Stab City, lay just ahead. We would find a pub, have a bite, and get back on our way with enough Guinness to carry us through to Dingle. Wrong. Our brief pitstop in Limerick proved to be one of the most chaotic nights that I can ever remember, and/or, kind of not remember. Suffice to say, we conquered Stab City. The three of us took over a pub, all in the name of Gerry Conlon. He was a hero to these people and it was a joy to bear witness. Courtesy of his devilish charm, he owned the place. It was a riotous celebration. The following morning, I awoke in an unfamiliar room, in what appeared to be an old hotel. Complete with red-eyes and full-on throbbing gristle somewhere within whatever had been spared of my brain, I somehow managed to contact Gerry in the adjoining room. “Where is the Lord Mayor of Limerick?” I asked, referring to David, who had been bestowed the honor the night previous. “He’s taking a shower” Gerry said, in a pained drawl. Apparently he woke up with some chick. He didn’t know where he was, let alone who she was. Gerry went on to tell me that David had said good morning and asked the girl very simply, “Did we fuck?” “I’m not sure,” came the reply from the sweet lady to the armless thalidomide, whose pincer claws had been hurled across the room. David thought for a moment, before calmly stating, “Well, we had better make sure …”

After picking myself up off the floor, we again made for Dingle, where we finally met Fungie. The three of us were in no state to do anything whatsoever, let alone get in a fucking boat with a bunch of tourists. I can recall us being looked down upon by our fellow shipmates, especially the children, for some reason. I felt dirty. But Gerry was as excited as an eight-year-old, as we clipped through the water watching out for the dolphin to occasionally rear a head and deign us with its glory on this most joyous of grey days that I can ever recall. Gerry always possessed the magical ability to ensure such miracles.

The pain of losing his father never left Gerry. He blamed himself for Giuseppe’s death and nothing I, or anyone else, could say to him would shift that blame. In quieter moments, he would tell me of his pain, of how troubled he was at having confessed to the Guildford pub bombing. In his mind, if he hadn’t confessed, his father might still be alive and the Maguire family, who were also wrongfully convicted of the pub bombings, would never have been sent to prison. He might have been dealt the torturous methods employed by the authorities to haul out the counterfeit admissions, but in his rush to self-condemnation, he set that aside. He could not forgive himself.

Gerry Conlon was a leader who became the central figure in the struggle to have the Birmingham Six released from prison, even addressing a Congressional Committee on the matter. Gerry was also an international human rights activist and he highlighted the harsh treatment meted out to the Australian aborigines and Native Americans. His activism didn’t stop there: he protested capital punishment wherever it reared its ugly head. For prisoners around the world, many of whom had been wrongfully convicted, Gerry Conlon was their only hope.

Yet, by his own admission, this man was a flawed character, as so many of us are. He often told reporters that he took drugs to ward off his demons. In 1998 he took the decision to go clean, but what followed was a six-year struggle, during which he repeatedly goaded himself to commit suicide. But he beat the monster; he got off his knees and he beat the monster.

This book is a tour de force, a warts-and-all depiction of the life of Gerry Conlon from the minute he walked out of the Old Bailey. Knowing him as I did, he wouldn’t have wanted it any other way. On every page, the colourful characters that inhabited Gerry’s life reach their hands out to the reader and invite them into a world rich in pathos, humour and irony. This is not a sad story. No, far from it. This is a chronicle of the triumph of the human spirit over extreme adversity. It is a story of hope. It is the story of a man I loved and would have taken a bullet for, as I know he would have done for me and all his loved ones. It was an honor to have known Gerry Conlon and to call him my friend.

Once we’d just left a bookstore in Dublin. Me with a handful of Brendan Behan’s books, and Gerry with a present – a beautifully handworked leather wallet, with one word etched onto it … “Saoirse”, meaning Freedom. It’s in my pocket as I write these words.

Johnny Depp

Vancouver

August 2017