Читать книгу Abandoned Places: 60 stories of places where time stopped - Richard Happer - Страница 11

ОглавлениеROSS ISLAND

DATE ABANDONED: 1913

TYPE OF PLACE: Explorers’ base camp

LOCATION: Antarctica

REASON: Death

INHABITANTS: 25

CURRENT STATUS: Preserved

THIS WAS A STOREROOM, SCIENTIFIC LABORATORY, A STABLE AND A HOME FOR TWENTY-FIVE MEN. THE HUT FROM WHICH CAPTAIN SCOTT SET OUT ON HIS FATAL JOURNEY TO THE SOUTH POLE STANDS LITERALLY FROZEN IN TIME, PRESERVED BY THE SAME SUB-ZERO CLIMATE THAT KILLED HIM.

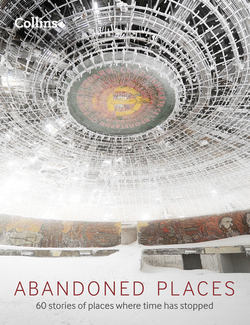

Abandoned crates outside Scott’s Terra Nova Hut, Cape Evans.

Antarctic basecamp, 1911

Tinned ham and whisky are stacked on the shelves beside jars of olives and anchovy paste, awaiting the return of the man who put them there. However, he never would step back into this cosy living space and enjoy the food he had left behind. His name was Robert Falcon Scott – and when he walked out of here it was to go to his doom in an Antarctic blizzard.

Scott’s sensational journey

When Scott left Britain on his attempt to be first to reach the South Pole, he was already a national hero. He had commanded the National Antarctic Expedition of 1901–1904, which included another great explorer, Ernest Shackleton. Scott and Shackleton had walked further south than anyone else in history: they got to within 850 km (530 miles) of the pole.

When he announced another Antarctic expedition, hopes were high that a Briton would be the first to stand on the bottom of the world. Scott’s expedition sailed from Cardiff in June 1910 on the former whaling ship, Terra Nova. It travelled via New Zealand and arrived at Ross Island, Antarctica in January 1911.

Ross Island is a fearsome place. Although little bigger than Anglesey, it has four huge volcanoes, two of which are over 3,048 m (10,000 ft) tall. This gives it the highest average elevation of any island in the world. The only inhabitants are half a million Adélie penguins. It is almost permanently ice-bound, shackled to the Antarctic continent by the frozen sea. However, in summer, it is reachable by boat – the most southerly such island in the world, making it an ideal base for Antarctic explorers.

As soon as they arrived, they set about erecting the prefabricated hut that would be home to twenty-five men throughout the Antarctic winter of 1911. It took a week to build the 15 m (50 ft) long and 7.6 m (25 ft) wide structure. The hut was insulated with seaweed quilt sandwiched between inner and outer double-plank walls, a design so successful that the men found it uncomfortably warm inside.

The interior of Shackleton’s Nimrod Hut has been literally frozen in time: the bedding, tinned food and even the men’s socks still await them.

The push for the pole

With the base established, the next task was to lay caches of supplies on the route to the pole. The Antarctic summer presented a window of relatively better weather and constant light, but it only lasted from November to March. The expedition team needed as many supplies laid down in advance as possible if they were to complete the 1,450 km (900 mile) trek to the pole – and return – in that time.

However, bad weather and weak ponies meant that the main supply point, One Ton Depot, was laid 56 km (35 miles) north of its planned location. This would cost the returning party dearly.

The expedition finally departed on 1 November 1911, in a caravan of motor sledges, ponies, dogs and men. Like booster rockets on the space shuttle, one by one the support teams turned back. It was five men on foot – Scott, Wilson, Oates, Bowers and Evans – who scaled the 200 km (125 mile) long Beardmore Glacier and set out across the lifeless Antarctic plateau towards the South Pole.

‘The worst has happened’

Scott and his party reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912. There they discovered that Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen had beaten them to their great prize by five weeks. In a flag-topped tent, Amundsen had left a note to the King of Norway and a request that Scott deliver it. ‘All the day dreams must go,’ wrote the anguished Scott in his diary. ‘Great God! This is an awful place.’

There was nothing for the distraught men to do but start the 1,300 km (800 mile) return journey. This was a savage undertaking, and the exhausted explorers were pained with frostbite and snowblindness. Edgar Evans died on 17 February after collapsing at the foot of the Beardmore Glacier.

The remaining four trekked on, but Lawrence Oates’ toes had become severely frostbitten and he knew that he was holding back his colleagues. On 16 March, Scott wrote in his diary that Oates stood up, said ‘I am just going outside and may be some time’, then walked out of the tent and was never seen again.

On 19 March the three surviving men camped for the last time. A ferocious blizzard kept them in their tent in temperatures of -44°C, and sealed their fate. They died of starvation and exposure ten days later. They were just 18 km (11 miles) short of One Ton Depot. Scott was the last to die.

A search party found the tent eight months later. Inside were the frozen corpses along with Scott’s diary. The explorers’ bodies were buried under the tent and a cairn erected on top in their memory. After a century of snowstorms, the cairn and tent now lie under 23 m (75 ft) of ice. They have become part of the ice shelf, and have already moved 48 km (30 miles) from where they died. In 300 years or so the explorers will once again reach the ocean when they will drift away inside an iceberg.

Frozen in time

Scott’s hut was reused by Ernest Shackleton’s team in 1915–1917, but was thereafter completely abandoned until 1956, when it was dug out of the snow and ice by an American team. They found that the sub-zero weather conditions had preserved its contents almost perfectly. It’s still there today, and it offers a fascinating insight into a place that is strangely familiar and yet situated in an utterly alien world.

The familiar brands show that even the boldest of Edwardian explorers loved his home comforts as much as we do: Heinz tomato ketchup (stoppered with a cork), tins of Lyle’s golden syrup, Fry’s cocoa and Colman’s mustard.

Stoves, lights, fur-lined boots and clothes, bedding and dog harnesses all lie where the explorers left them. A corridor is still piled with cuts of seal blubber, which would have been used for cooking, heating and in lanterns. Dishes stand neatly stacked on shelves, cups hang from a row of hooks. Scott’s worktable has an open book, a copy of the London Illustrated News and a stuffed Emperor penguin on it. Scientific equipment fills a workbench, and the darkroom of the expedition photographer still has its chemicals and plates. There is even the rusting frame of a bicycle and some hockey sticks – after all, these men needed some way of passing their time.

The hut must then have been a crowded, noisy and smelly place with two dozen men clustered round the table, trying to keep their bodies strong and their spirits up. It is bereft of living beings now, but there is life here all the same. One only has to look at the clothes, the maps, the lamps and the tins of sweet fruit stacked in hope for a return that never came, to feel the power of the human spirit.

Robert Falcon Scott in the Cape Evans Hut, October 1911.

Shackleton’s hut

Scott’s is not the only preserved hut in the Antarctic. Ernest Shackleton’s 1907–1909 Nimrod expedition fell short in its attempt on the pole, but made a successful first ascent of Mount Erebus, Antarctica’s second highest volcano. Their hut on Cape Royds, 12 km (7.5 miles) from Scott’s on Cape Evans, stands in a similar state of preservation.

Portraits of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra still hang on the walls inside, and the shelves are stacked with 5,000 personal items belonging to the nine men who wintered here in 1908. Some of the 450 tins of baked beans and 540 lb of golden syrup that they brought as supplies are still stacked on the shelves.

These Antarctic huts continue to offer up surprises. In 2010, a team found two crates of brandy and three crates of whisky buried under the Nimrod hut floor. Shackleton had originally taken 300 bottles of Mackinlay’s finest malt whisky – although a teetotaller himself, he thought his men might appreciate a warming dram in the endless Antarctic night.

The legends live on

The science started by Scott’s expedition is continuing even today. The readings logged by the early 20th century instruments are now being compared to current values, to help us understand the effects of climate change on Antarctica.

The buildings were given a little loving renovation in 2010. Despite the brutal environment in which they stand, they will live on a little longer as shrines to the men of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration and their incredible achievements.