Читать книгу Abandoned Places: 60 stories of places where time stopped - Richard Happer - Страница 9

ОглавлениеANI

DATE ABANDONED: Eighteenth century

TYPE OF PLACE: Medieval city

LOCATION: Turkey

REASON: Political

INHABITANTS: c. 200,000

CURRENT STATUS: Ruined

A MILLENNIUM AGO THIS WAS THE CAPITAL CITY OF AN EMPIRE THAT STRETCHED FOR HUNDREDS OF KILOMETRES ACROSS EURASIA. IT SURVIVED VIOLENT CENTURIES OF CLASHING KINGS ONLY TO BE FORGOTTEN WHEN THOSE EMPIRES THEMSELVES FADED. NOW IT LIVES ON IN RUINS, FAR FROM THE TOURIST ATTRACTIONS OF TURKEY, A GILDED SHADOW OF ITS FORMER POWER AND GLORY.

The medieval megacity

There were few more magnificent cities anywhere in the world in AD 1000. Perhaps Baghdad could boast the same architectural majesty, and maybe Constantinople had a similar wealth of international trade. But Rome was in ruins, London was a mere Saxon market town and New York was a wooded island. This is Ani: the key military stronghold, the capital city and the cultural heart of a mighty Armenian empire.

Ani lies deep in eastern Turkey, over 1,450 km (900 miles) from Istanbul. Even the nearest town, Kars, is 48 km (30 miles) away. There is precious little in the hinterland but sheep and goats. The plains here roll on and on in every direction, only ended at last by a horizon of slumbering mountains. This feels a long way from civilization; yet a millennium ago it was the centre of one.

The city of 1001 churches

Just before the Norman kings expanded their rule into England, the Bagratuni royal dynasty was crushing local tribal leaders in the area between the Black Sea, Caspian Sea and eastern Mediterranean to create an empire of their own. From AD 961 to AD 1045, Ani was the undisputed capital city of a kingdom that stretched for over 800 km (500 miles) from west to east and 600 km (373 miles) from north to south – a territory that would now include Armenia, eastern Turkey and parts of Azerbaijan, Georgia and northern Iran.

The city was blessed with a superb defensive situation: a steep-sided triangular plateau rising from the ravine of the Akhurian River and the Bostanlar Valley. It also happened to lie at a nexus of trade routes that connected Syria and Byzantium with Persia and Central Asia. The canny Bagratuni capitalized on this location to transform the city into a trade hub close to the Silk Road.

When the seat of Armenian Catholicism relocated to Ani in 992, the city also became the centre of a religious golden age. Churches popped up like desert flowers after a flood, and there were no fewer than twelve bishops within the city leading the faithful in prayer. Ani was famous throughout the region as the ‘City of 1001 Churches’ and the ‘City of Forty Gates’. It was also the sacred resting place of the Bagratuni kings, with an extensive royal mausoleum. The city’s population grew from around 50,000 in the tenth century to well over 100,000 a hundred years later. It probably topped 200,000 at its peak.

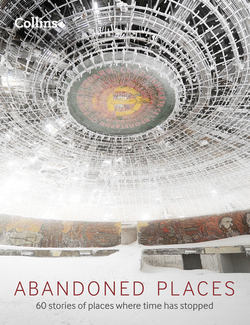

Earthquakes have shattered the abandoned churches, mosques and walls of Ani.

Trophy of the empire builders

The city’s strategic location made it a pawn in a vast Eurasian game of chess. It was fought over, sacrificed, taken, even promoted to the status of a queen. The names of the nations fighting changed over the centuries, but Ani saw them all come and go.

From 1044 it came under a wave of Byzantine attacks. In 1064 the town was captured and the inhabitants put to the sword by Seljuk Turks. Over the next 200 years it was owned by Muslim Kurds, Georgians and then Mongols. In the fourteenth century Ani was ruled by another Turkish dynasty, and then the Persians took over, before it became part of the mighty Ottoman Empire in 1579.

By now the city’s day in the sun was dimming into its twilight. The earth’s great empires now lay elsewhere. By the time the site was completely abandoned in 1750, there was only the equivalent of a small town left within the walls.

Lost and found

Ani slumbered in its little nook for a century or so. It was then rediscovered by delighted archaeologists and excavated in 1893. Several thousand of its most important treasures were uncovered and removed before the site could be looted, as happened in the First World War. At the end of that conflict the city was briefly back in Armenian hands before finally being incorporated into Turkey in 1921.

Today the best-preserved monument in the city is the church of St Gregory of Tigran Honents, completed in 1215. On its outer walls, elaborate animal carvings frame panels filled with ancient text. Inside, its frescos still shine with azure, gold and crimson hues as daylight floods the chamber through windows high in the central tower.

Several other churches stand in various states of preservation. A couple look ready to welcome worshippers; some are cloaked in grasses and lichens. The Church of the Redeemer stands like one half of a huge nutshell, its inside exposed to the elements; the church was cleaved in two by a lightning bolt in the 1950s. The rubble from the fallen half has been heaped forlornly in a poor attempt at protecting the half that remains standing.

The Cathedral of Ani has fared better. This architecturally stunning building was completed in AD 1001 and is famed for its pointed arches and clustered piers. These long predate the gothic style of architecture, which would eventually make such features commonplace.

Just down the street from the cathedral is the mosque of Minuchir, the first mosque to be built on the Anatolian plateau. Its 1,000-year-old minaret survives intact along with much of its prayer hall.

Ani was once encircled by powerful defensive walls, and many of these battlements and towers still stand. The walls were doubled in thickness at the northern side where the city was not protected by a river or ravine. Today these sections remain . . . ready to face an enemy that will never come.

There are also the remains of a convent, bathhouses, palaces, streets with shops and ordinary homes, and the abutments of a single-arched bridge over the Arpa River. A few minutes’ walk away in the gorge is an early solution to urban overcrowding – a satellite town of caves cut into the cliffs. The same high architectural standards are evident here: there is even a cave church with frescoes on its walls and ceiling.

The city’s future survival

Earthquakes in 1319, 1832, and 1988, as well as blasting in a nearby quarry and even target practice by the army have all damaged the city’s ancient architecture. Some ham-fisted repair work has done more harm than good. Currently, the city is on the ‘at risk’ register of the World Monuments Fund.

Ani’s sovereignty, meanwhile, remains contested. Today the ruins sit just inside Turkey; Armenia lies a piece of rubble’s throw away across a disputed frontier. Although open to visitors, it remains fenced off in a Turkish military enclave. History would suggest that this may not always remain the case. Ani may have been forgotten by the world at large for several centuries, but the Armenians have always remembered. One day they may yet reclaim their ancient city.

The church of St Gregory of Tigran Honents looks out over the river gorge and the empty plain beyond.