Читать книгу Heroes, Villains and Velodromes: Chris Hoy and Britain’s Track Cycling Revolution - Richard Moore - Страница 10

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

The Wellydrome

Meadowbank velodrome, Edinburgh, 1994

Of all the ill-considered sporting arenas in the world – from the ski centre in Dubai, to the two football stadiums that back onto each other in Dundee – Edinburgh’s velodrome has to be up there with the very daftest.

Not that there is anything wrong with the track at Meadowbank, which is a good, internationally-renowned wooden oval that, in its day, has hosted top class competition, producing world championship medal-winning cyclists and one Olympic champion – Chris Hoy. But there is one glaring, not to mention fundamental, glitch: one oversight; one fatal flaw; one unforgivable omission. It has no roof.

We are talking here about a velodrome in Scotland, one of the wettest and most inclement countries in the world, which is rendered unusable every time it rains. A few drops are enough, in fact, to have them postponing the action and running for the covers, à la Wimbledon.

Even more remarkably, it is a state of affairs that has existed since 1970, when the velodrome was built for the first Edinburgh Commonwealth Games. Since then there have been numerous proposals to build a roof, but the roof – unlike the rain – has consistently failed to materialize, as a consequence of which the poor wooden boards have suffered, oh how they have suffered, through their constant exposure to the elements.

Still, that the track was built at all was something of a triumph for the sport in Scotland. The country had several concrete cycling tracks – longer than a wooden velodrome, with comparatively shallow banking – and there was a proposal, popular with the spendthrift council, to hold the track cycling events of the 1970 ‘Edinburgh’ Commonwealth Games at Grangemouth, twenty-five miles away. One man who led the fight for an Edinburgh velodrome was Arthur Campbell, then president of the Scottish Cyclists’ Union and a consummate sports politician, who went on to hold high-ranking positions in the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) and the Commonwealth Games organization. In the end Campbell won, and hundreds, if not thousands, of Scottish cyclists have since had cause to be grateful. The facility built at Meadowbank, adjacent to the main athletics stadium, was state-of-the-art. It remains state-of-the-art – by 1970 standards, that is.

Be that as it may. There is a nice link between Campbell, the man who drove through the plans for a velodrome in Edinburgh, and Hoy, who would go on to become its most successful ‘product’. Twenty-four years after its construction, and with Hoy having just made a tentative start to his track cycling career, the young cyclist attended a training camp in Majorca. It was his first overseas training camp, and it fell on his eighteenth birthday. One of the senior cyclists on the camp was Campbell, then in his mid-seventies, but still showing the youngsters a thing or two on the daily training rides. Hearing of Hoy’s birthday, Campbell pedalled off to a nearby village, several kilometres away. When he returned, he had something balanced precariously on his handlebars. ‘Many happy returns,’ he said to Hoy. It was a birthday cake.

Hoy had started riding on the track, thanks, again, to Ray Harris. The East of Scotland Cycling Association had a fleet of around a dozen track bikes stored at the velodrome, which could be used by members of the Dunedin Cycling Club at their weekly ‘track night’. It was at one of these track nights, in April 1991, that Hoy had his first outing on the boards of the Meadowbank Velodrome. ‘I remember being scared and intimidated by it,’ he says of the track. ‘Walking through the tunnel, under the track, and then out into the track centre and realizing how steep the banking was … it was daunting. And there was an etiquette about riding there that I didn’t understand.’ Here Hoy slightly contradicts Harris’s claim that Dunedin was a ‘youthful’ club. It was true that its membership was youthful as far as cycling clubs went, but it was, says Hoy, all relative. There weren’t many as young as he was, which was fifteen. ‘It wasn’t that they weren’t friendly to young riders,’ he says, ‘it was just that there weren’t many young riders.

‘I remember being given a track bike and starting riding on the track, then, eventually, being led round it by one of the older riders. We followed behind him in a string. It was really scary at first. It just didn’t look physically possible to stay upright on the steep banking; I thought you’d slip down unless you were going really fast. But when you rode around on the black line [near the bottom] and realized that it was just as steep there as it was at the top, then you realized that you could ride at the top as well. So you could start to move up the banking, and that was exciting.’

It was fortunate for Hoy that there was a velodrome – still the only one in Scotland and one of only a handful in Britain – in his home city. ‘Our club was officially based at the velodrome,’ explains Harris, ‘as much because we were trying to keep it open as anything else. The history of that track has been one of bumps along a very rocky road. After the 1970 Commonwealth Games it had quite a following, because it was such a good track. The only drawback was the everlasting weather problem. Events could be cancelled with a drop of rain. They still can, and regularly are. But it got to the stage where it was almost matchwood; there were splinters appearing of astronomic proportions; everything leaked.’

At that stage, on the brink of becoming matchwood, the velodrome was rebuilt for the 1986 Commonwealth Games, at a cost of £450,000, but still with no roof. And it rained a lot during those games, playing havoc with the cycling programme. Thus was the velodrome christened – by Prince Edward, apparently – the ‘Wellydrome’.

Although the Dunedin Cycling Club was based at the Wellydrome, track racing was merely one activity. They were very active in the other disciplines – road and now mountain biking, too – and they were all encouraged. Hoy, as a consequence, did a considerable amount of time trialling and road racing, even competing in the 1994 Junior Tour of Ireland, a mini-Tour de France-style stage race and a major event for juniors, held over nine days, with stages of sixty to seventy miles a day. For juniors this was a gruelling, demanding event, in many cases providing their first experience of a proper stage race, and Hoy did reasonably well. As he says, he was never going to be a climbing specialist – though he wasn’t big at the time; ‘he was a wee sparrow,’ says his father, David – but on the fast, flat stages he could remain safely in the ‘peloton’ and even get near the front in the hectic sprint finishes. He managed two top-ten finishes on road stages.

Earlier road race outings hadn’t been so successful. Having travelled to the north of Scotland for a weekend of racing in and around the town of Forres, Hoy was unfortunate to puncture as the first road race was starting, within metres of having left the neutralized zone. He stopped to get a wheel change from the following ‘service’ car, then began to chase and appeared to be successful. But when he got within thirty metres of the rear of the peloton – almost touching distance – they began to speed up; he dropped back and never got close to them again.

He seemed to take to the track, though – or take to it as well as anyone when confronted by the steep wall-of-death-style banking, which, as Hoy says, was a daunting prospect. But he enjoyed it from the start. ‘You enjoy what you’re good at,’ he says. ‘I found that I did okay on the track and enjoyed it from day one. I started doing the weekly track league, on a Tuesday evening, and really enjoyed the 500 m handicaps. Being so young I’d start with about a lap-advantage over the big boys. I’d only be racing about half the distance they were, so it’d be flat out and I enjoyed that kind of effort – it was a bit like the start of a BMX race.

‘Every week I’d hear the older riders coming up behind me – whooom! – and then sweeping past, but I found I could hold them off for a bit longer each time. I could see I was improving, which felt good. I remember the first time I won one of those races – it was a great feeling. Though it did mean that my handicap got smaller. The better I did the harder it was to win.’

But to say that Hoy took to track cycling like a duck to water would be stretching it. He did suffer teething troubles. Even at the 1994 national track championships – immediately prior to the Junior Tour of Ireland – there was an incident that Ray Harris puts down to ‘inexperience’. Harris was there helping – though Hoy had joined a new club, the City of Edinburgh Racing Club, at the start of that year – and he was horrified when his protégé took to the start line of the junior kilometre with a spanking new pedal-and-shoe ensemble. He had got himself a clipless system, whereby shoes snapped into pedals, and were held there, rather than being attached by old-fashioned toe-clips and straps, which were still overwhelmingly the choice of track riders for whom reliability was the most important consideration.

‘You don’t try new tricks on the day of the competition!’ exclaims Harris. ‘Of course, he starts his effort, and in the strain of starting, he pulls his foot out of the pedal. My god! In the kilo there’s a rule that if you have a mechanical problem in the first lap, or fall off, then you can start again. But a pulled foot doesn’t count as a mechanical, so the commissaire [referee] is looking at me, saying “Push him over!” It’s an old trick, that, the trick of falling off your bike if your foot comes out. But Chris didn’t realize. It’s a learning experience, but it can be costly if it’s the one chance you’ve got as a junior. However, I think the least perturbed by all that was Chris himself. He seemed very calm. I was having kittens.’

To make matters worse, Hoy had ‘previous’ in this regard. At the 1992 British championship – his first, where he had the experience of riding around, awestruck, behind the new Olympic champion Chris Boardman – he had also pulled his foot out of his toe-clips and straps during his starting effort, riding the entire race with his foot resting limply on top of the pedal. Two years later, when he caused Harris to have kittens by pulling his foot out of his new pedals, he at least managed to clip his foot back in, and placed fifth in the junior kilo. But it could and should have been so much better, says Hoy, who feels that the 1994 championships – about which more later – were significant for being ‘the first time I realized I had potential. I probably would have won the kilo if I hadn’t pulled my foot out.’

It had been at the end of the 1993 season that Hoy felt it time to leave the club environment of the Dunedin, and the mentorship of Harris, to join a more specialist and more serious club, whose overriding focus was track racing. But he didn’t forget Harris, who explains: ‘I’ve had lots of lads come through the club and most of them move on to the next stage of their life and you never hear from them again, or see them; they become adults, get married, have kids, move on, though they probably keep a memory of it. But if I send Chris an email he always replies. It’s one of the endearing things about the lad. He keeps in touch, in quite regular contact really.’

Stepping into Harris’s shoes as mentor was Brian Annable: the inimitable, irascible Brian Annable – the Brian Clough of Scottish cycling. Annable ran his team – the City of Edinburgh Racing Club – with all the obsessive zeal, and occasional bursts of bad temper, of Clough. And the truly remarkable thing is that, twenty-five years on, he is still doing it. Since November 1982, when the City of Edinburgh Racing Club was established, Annable has been at the helm, skippering the good ship through some choppy waters, but invariably to success – which, in his book, means medals in British championships. Sitting in his large house in Edinburgh, behind a pile of immaculately blue-bound City of Edinburgh Racing Club annual reports – all twenty-five of them, in order – the well-spoken Annable spells it out, like an army major listing battles won: ‘By 2006, seventy-six championships and two-hundred and forty-eight medals, won by club members in British championships.’

Annable has been the driving force behind those seventy-six national titles and two-hundred and forty-eight medals. He was a competitive cyclist himself, and in the British team pursuit squad for the 1952 Olympics, but his training, as an architect, got in the way of his cycling ambitions. A peripatetic career took him to Coventry, then to Manchester, ‘to clear the slums of England in five years’, and finally to Edinburgh, in 1970, just in time for the Commonwealth Games. ‘I had been out of bike racing activity for several years,’ he says, ‘but I was appointed as deputy chief executive of the national building agency, based in Edinburgh.

‘I went to Jenners [Edinburgh’s big department store] on the first morning of the Commonwealth Games; down in the basement, where I was told I’d get tickets. But they had no plan of the track or anything,’ he says with disgust and disdain. ‘They didn’t know where the finish line was!’ Clearly this offended Annable on two fundamental levels – it showed an ignorance of sport, and an ignorance of the architecture of the arena. ‘If you’re in the left-hand end, where the track goes up, you can’t see the finish. And I ended up with tickets there, because they didn’t have a bloody clue.

‘The problem,’ he continues, now on a roll, ‘is that the track was not done properly. For some reason the city engineer’s department was involved in designing a cycle track, though they had no knowledge.’ He discusses some complicated-sounding facts pertaining to cycle tracks, mentioning German designers and UCI manuals, longitudinal expansion, roof trusses, metal angle irons, and slotted holes.

So, is he saying that there were no velodrome specialists involved in the building of the Edinburgh velodrome? ‘No! That’s what amazes me,’ he replies. ‘It was a bunch of amateurs. But somebody must have known something; if someone contacted Schuermann [the renowned German architects, reputed to have built 125 velodromes worldwide] then I wouldn’t be surprised.’

After the 1970 games Annable found himself down at the velodrome on an increasingly regular basis. A Scot, Brian Temple, from Edinburgh, had, surprisingly, won a medal at the games – silver in the ten-mile scratch race – and it provided evidence that Scottish cyclists could compete on such a stage, after all. There was also much in the ‘build it and they will come’ mantra of Field of Dreams, the baseball movie. The state-of-the-art Meadowbank velodrome proved quite a draw for cyclists from throughout Scotland during the 1970s.

But there was little organization to it. And there was certainly no pathway from participation to elite competition. When talented cyclists emerged, they had to make their own way. That is when mistakes tend to be made, and repeated ad nauseam.

In 1982 another talent emerged: Brian Annable’s son, Tom. With Eddie Alexander – a Highlander based in Edinburgh – he enjoyed some success at that year’s British championships, winning bronze in the junior points race. Two days later Alexander won bronze in the junior sprint. Incredibly, says Annable, these were the first two medals ever won by Scots in the British championships. ‘And they were getting no support in Scotland!’ he adds in characteristically bombastic fashion.

That winter Annable sat down with Alan Nisbet, ‘Mr Track Cycling in Scotland’, and discussed forming a specialist track club whose remit would be to ‘bypass Scotland and target success at British level’. They talked to Arthur Campbell, who agreed that the track cyclists needed more support but felt they should do it within an existing club. Annable was having none of that. ‘I got so fed up with the Scottish approach, still am, because it’s more concerned with the importance of people who are office bearers than with talented young riders. Bunch of blithering idiots! They were stuck in the past, obsessed with time trialling and with no advertising, sponsorship or money. They didn’t want to support people. Arthur was different, he was progressive, but he was keen we be part of a bigger club. In the end we said, “We’re going to do our own thing, we’ve got two youngsters here [Tom Annable and Eddie Alexander] with enough talent to start it, and others who are being ignored.”’

Annable wrote the constitution for a new track club, which remains, word-for-word, to this day, and appears on the first page in all twenty-five of those annual reports:

Cycle racing at the international level, including the World Championships, the Olympics and Commonwealth Games, and the British Championships, recognise champions in two road events and seven to nine track events.

In 1982 two Scottish junior riders won bronze medals on the track at the British championships. Eddie Alexander from Inverness in the Sprint and Tom Annable from Edinburgh in the Points race championship. It was clear to them and some other young Scottish track riders that they would have to concentrate their efforts and seek out specialized training and coaching and travel to competitions outside Scotland, if they were to have a chance of winning championships at the British and international levels. It also became obvious that an organisation devoted to this purpose was a prerequisite to success and that there was no such organisation in Scotland. Talks were held with an objective of winning medals at the British level, concentrating mainly, but not exclusively, on track racing and composed of young riders who were prepared to train, travel and race as necessary to reach that objective. It would be necessary to recruit expert coaching and team management and financial support.

The City of Edinburgh Racing Club was formed in November 1982. The country’s top track riders were recruited, and in 1985 the club could boast its first British champions. ‘Scotland has never had a British champion in track racing,’ read that year’s annual report. ‘It now has two: 1km Eddie Alexander; 20km Steve Paulding.’

The club was not wealthy. Sponsorship was modest and numbers were kept low. ‘I got sponsorship from the council, but I only asked for £1,000,’ says Annable, ‘because my experience, and advice, was to never go for a big team. Keep it simple and small. We’ve got nineteen members now [in 2007]. It’s always been a low number.’ Membership was – and is – restricted. ‘In terms of criteria for joining … well, I don’t think we’ve ever had anybody we didn’t know,’ says Annable. ‘It’s a small part of a small sport, so we know the riders. And we’ve always gone for riders who were talented and keen to travel – ambitious.’

Other individuals and companies put money into the club. In the early days they included Joe McCann, who gave £1,000. He described himself as ‘an enthusiastic optimist’. This was the kind of sponsor that clubs such as the City of Edinburgh RC tend to attract and upon whom they depend.

Within a few years, the club, by now known – and feared – as ‘The City’, was achieving its objectives. In fact, it was wiping the board. The City was so dominant in British track racing that in 1988 it was likened to the mafia by Kenny Pryde, a reporter for Cycling Weekly magazine. ‘The City of Edinburgh “mafia” were to be seen sitting at trackside cheerfully exhorting their team-mates to greater efforts,’ read Pryde’s report, which prompted a response, published in the magazine the following week. It was a letter that appeared beneath the headline ‘Message from the Edinburgh Godfather’:

Maybe your reporter Mr Pryde had little joke about the enthusiasm of members of the family encouraging the boys in the team. He calls them a ‘Mafia’, but the boys don’t understand what this means. I have arranged for one of the boys to drop in on him one night in Glasgow to discuss the matter, and to make him a little offer I know he won’t refuse.

Brian Annable, Edinburgh

Eddie Alexander was the club’s star in its early years and in 1986, at the second Edinburgh Commonwealth Games, he won a bronze medal in the men’s sprint, beating England’s Paul McHugh in the ride for third. That and other successes earned him selection for the world championships in Colorado Springs, from where he sent Annable a postcard, which he still has. On one side there is a picture of the majestic San Juan mountains, and on the other, beneath the date (19 August 1986), the scrawled message: ‘Dear Club. Very hot and sunny out here. Having a real good time – these BCF [British Cycling Federation] holidays sure are good value. I think we’re going to fit in some racing next week at the velodrome. Wish you were here. Eddie.’

He was joking about it being a holiday but it might as well have been, because men’s sprinting, the blue riband track discipline, was a closed shop. Alexander, the only British rider, had about as much chance of making an impression as Eddie the Eagle had of not embarrassing himself in a ski jump. Check the four semi-finalists: Michael Huebner, Lutz Hesslich, Ralf-Guido Kischy and Bill Huck. They had one rather significant thing in common, these four semi-finalists. They were all East German.

Now, you can speculate all you like about why the East Germans were so dominant. They were certainly awesome physical specimens – extraordinary physical specimens. There is a clip of a Huebner sprint, from 1990, that has proved popular on YouTube. Type in the words ‘pumped up Huebner’ and you will find it: Claudio Golinelli, the Italian, against Michael Huebner, in the final of the world sprint championship in 1990. Huebner, resembling the Incredible Hulk, is majestic, utterly impervious, while the words of the American commentator are unintentionally humorous. ‘With that show of upper-body strength [from Huebner] I think Golinelli will be heading for the health club,’ he muses, before suggesting: ‘He is on the podium today, perhaps starring in Rocky VI next.’

Not to suggest that Huebner – nor indeed Hesslich, Kischy or Huck –did anything illegal. But East Germany, a country of fewer than 17 million people, was, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the dominant Olympic force, in particular in sports such as swimming, athletics and cycling, for reasons that are now a matter of public record. Thousands of East German athletes were given performance-enhancing drugs during that time; many didn’t know what they were taking – some thought they were vitamins. Numerous ex-athletes have since suffered terrible health problems, including liver cancer, organ damage, psychological trauma, hormonal changes, and infertility. Eventually the German government set up a fund for doped athletes to pay medical bills arising from their years of being doped. By the March 2003 deadline 197 athletes had applied for the compensation of $10,000 each.

In 1987, Alexander’s second world championship, he qualified thirteenth but, once again, all four semi-finalists were East German. But by now there was also another Scot – and a City of Edinburgh club-mate – at the championships in the form of Stewart Brydon. Brydon qualified twenty-first and told Cycling Weekly: ‘The worlds have been an experience and it’s made me realize how much work needs to be done. The Eastern Bloc countries are in front, but not by that much, and it’s done me good to see them. You think they aren’t human when you read what they are doing, but on the line they have fear in their eyes, the same as everyone else.’

Alexander also earned selection to the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, and it was here that he demonstrated just what a talented rider he was – and hinted at how far he might have gone had the playing field been level. Being the Olympics, there was only one rider per nation, which meant a guarantee of only one East German in the semi-finals. And Alexander, incredibly, made it that far, finally finishing in the worst place of all – just out of the medals in fourth. Lutz Hesslich, ‘the man with the broadest shoulders in cycling,’ was the Olympic champion, as he had been in 1980. Alexander, though, became the first British sprinter to reach the last four since Reg Harris, some forty years earlier.

The near-miss prompted Alexander, an amateur whose day job was to design power stations, to reflect on the ‘Cinderella status’ of British track racing: ‘A lot of these guys have been in training camps or preparing in Europe. What did we get? Five days at Leicester [the outdoor track which hosted the British championships] and it rained on two of those.’

In the following years Brydon inherited Alexander’s title as Britain’s fastest sprinter, though he didn’t make the same impact as Alexander on the international stage. At the British championships the City of Edinburgh sprinters were dominant – the East Germany, if you like, of the British scene – with Alexander, Brydon and Steve Paulding taking a clean sweep of the medals in 1989. The success in this discipline satisfied the club’s ‘Godfather’, Annable, for it was sprinting that enthused and excited him. As far as he was concerned, it was real racing.

‘You have to make a distinction between an athletic event and a race,’ says Annable. ‘My emotions are for racing, which for me means match sprinting. The most boring event in the world for me is the qualifying round for the women’s pursuit. Riding fast against the watch doesn’t excite me, whether it’s the kilo, pursuit or team sprint. That’s not a race! Whereas the racing from the quarter-finals of the sprint is electrifying. It appeals to my emotions.

‘When I started there were two ways into the sport of cycling,’ he continues. ‘On the road you had the inspiration of the Tour de France, the mountains and all the rest of it. But in Britain at that time you couldn’t road race – massed start racing on the roads was banned. You could time trial or ride on the track, and track racing was huge. Heavyweight boxers and sprint cyclists were superstars in those days.’

And the biggest star of all was Reg Harris, whose bronze statue now looms over the final bend of the Manchester Velodrome, the home of British cycling. Harris, born in 1920, won the amateur world sprint title in 1947, following that with two Olympic silver medals in 1948, in the sprint and tandem sprint, despite having fractured two vertebrae three months earlier, then falling and smashing his elbow just weeks before the games. But it was as a professional that he made his name: he won the world sprint title four times between 1949 and 1954. Then, perhaps even more famously, he came back twenty years later, winning the 1974 British title at the age of fifty-four.

Harris embodied the familiar traits of the star sprinter. He had panache, and, with his huge legs and puffed-out chest, the confident swagger of the sprinter. Backing up Annable’s claim that the sprinters were huge stars, his feats also captured the imagination of the wider sporting public: in 1950, for example, he was named Sportsman of the Year by the Sports Journalists’ Association, and he was twice named BBC Sports Personality of the Year.

Harris was colourful and controversial. He married three times, ran numerous businesses, including the Fallowfield Stadium velodrome, which he renamed the Harris Stadium, and started a ‘Reg Harris’ line of bikes. The man dubbed ‘Britain’s first cycling superstar’, and known as ‘Sir Reg’ on account of his incongruously cut-glass accent and debonair manner, died after a stroke in 1992.

In some ways it seems strange that Harris is held up as the gentleman of British cycling and the grandfather of British sprinting. He was certainly utterly ruthless in pursuit of victory, and, according to some witnesses, not above skulduggery or dubious tactics. Tommy Godwin, the other great British track rider of the 1940s and 1950s, writes about Harris in his autobiography, It Wasn’t That Easy, and the picture that emerges is of a devious, scheming rider. In one race, writes Godwin, ‘I passed Reg on the final bend and was into the straight when suddenly a pull on my saddle almost stopped me. My friend Harris [safe to assume he is being sarcastic here] wanted to win the final sprint in front of his home crowd, which he did. My response was to get to him as soon as possible and physically attack him.’ Godwin also makes allegations of race-fixing and, at one point, tells of an exchange with a Belgian soigneur – a cyclist’s masseur/trainer/unofficial doctor – named Louis Guerlache, who offers him ‘a little help’. Writes Godwin: ‘The inference of this I understood. I immediately said, “No, if I can’t do it with what I have been gifted with then I don’t want it.” But at the mention of “No” Louis had picked up all the things laid out for the massage, threw them into his suitcase, which was packed with about half a chemist’s shop, and stormed away.’ Later in his book, Godwin notes wryly, and without comment, of one of Harris’s world titles that: ‘His trainer was Louis Guerlache, a Belgian.’

Annable’s eyes light up as he remembers Tommy Godwin, his own particular favourite. He, to Annable, was a real racer. And he has seen enough of them now come through the City of Edinburgh, with the club snapping up any track cyclist with a modicum of talent and plenty of ambition. Meadowbank has always proved the testing ground; the weekly track league, on a Tuesday evening, provides a showcase, or audition, for any aspiring young rider. Arguably no other track in the UK has produced such a conveyor belt of talent, or so many British medallists.

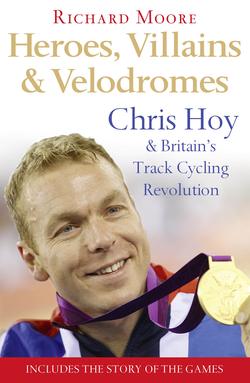

There is no question, though, about who is the best of them all. Chris Hoy is the only individual world champion – with seven individual world titles among his nine gold medals – and, of course, the only Olympic champion to have taken his first pedal strokes at Meadowbank, and to come through the ranks of ‘The City’.

Yet Annable, asked if Hoy is the most talented rider he has worked with, hesitates. ‘His head wasn’t good initially,’ he says, eventually, and in his very matter-of-fact way. Annable is talking of the 1994 national track championships at Leicester, where a pulled foot led to Hoy finishing fifth in the junior kilo. He also placed sixth in the junior points race, but it was in the sprint – Annable’s favourite – which served as a demonstration of his potential. Hoy qualified fastest, with 11.777 seconds, beating the best junior sprinter of the day, James Taylor. ‘James Taylor’s mother came over to me after that,’ recalls Annable, ‘and said, “God, you’ve got another one – who’s he?”’

Someone else who was impressed was Doug Dailey, the national coach. He was sitting in the stand, just behind Hoy’s parents. ‘I overheard him saying, “That kid looks like he’s got something about him,”’ recalls David Hoy. ‘I spoke to him later, told him I was Chris’s dad, and he repeated what he’d said. Chris was over the moon to hear that.’

He progressed to the final, to meet the experienced Taylor in a race that also saw Hoy make his first TV appearance – it was broadcast by a new satellite sports channel called Sky Sports. ‘He got to the final,’ says Annable, ‘against Taylor, and I said, “Look Chris, you may be faster, but he can stop you riding. He’ll put you against the barriers and do whatever it takes to stop you.” I told him exactly how to get out: “Don’t chicken out!” I told him. “He can’t hurt you; he can intimidate you.” But Chris was outmanoeuvred, and Taylor got the better of him, beating him in two straight rides.’

This is what Annable means with his assertion that Hoy’s ‘head wasn’t good initially’. It seems a harsh judgement on a seventeen year old. He must be surprised that Hoy became his first and only Olympic champion. ‘You have to give him his due,’ says Annable, grudgingly. ‘His single-mindedness has been phenomenal and so has his work rate. It took him a long, long time. He is now much bigger, physically, through specialized gym training, but it’s taken him years. When he made up his mind, and had the confidence to know what to do, I mean, you can’t fault him’ – much as it would seem Annable would like to! – ‘he has really done the work. But other riders have been better at knowing how to win a race. Craig MacLean, for example.’ In MacLean Annable discovered the kind of rider he liked, almost – almost! – without qualification. ‘Craig won sixteen gold medals with our club,’ he says with evident pride. ‘Chris won six,’ he adds less effusively.

If the diplomatic Hoy has a criticism of the City it is that, although expectations were high in terms of successes, support off it, in the form of coaching and guidance, left much to be desired. Hoy says he was ‘thirsty for knowledge. I knew I wasn’t doing the right training, that there were pieces of the puzzle missing. I was desperate to know what I should do, and I kept asking questions, but there weren’t many answers.’

It is also fair, however, to say that although Hoy’s progress in his early days with The City demonstrated he had talent, there was little to indicate that he would go on to become arguably the country’s most successful ever track rider. As well as his silver in the British junior sprint in 1994, he claimed two gold medals in the Scottish championships, winning the junior sprint and pursuit. Annable, typically, is dismissive. ‘The Scottish championship is a fish-n-chipper,’ he snorts, a ‘fish-n-chipper’ being one of those baffling pieces of sporting parlance – in cycling, it means inconsequential, rubbish.

October 1994 brought a significant development for the sport in the UK. The country’s first indoor velodrome was built, in Manchester, as part of the city’s planned bid for the 2000 Olympics. Costing £9 million, it proved an instant hit, not least with the City of Edinburgh Racing Club, who transferred their dominance from the traditional home of the national championships, in Leicester, to their new home in Manchester. In 1995, the first year the championships were held on the indoor track, the club won a new event, the team sprint. Hoy figured in that gold-medal winning team and also – illustrating his earlier point that he did have ‘an element of aerobic potential’ – in the silver-medal winning team pursuit team, contested over 4,000 m.

There began to be talk, already, of a ‘Manchester effect’ – namely, a raising of the standards of Britain’s track cyclists, who, finally, were able to train all year round, whatever the weather. It meant no more running for cover at the sight of rain. A Manchester Super League was established, with races held in the winter, traditionally the off-season, and with the riders representing cities, pitting Edinburgh against London, Birmingham, and Manchester.

But of all the talent that was beginning to shine from the mid-1990s, it was another Highlander – MacLean – who stood out. After Alexander, though Brydon was successful at British level, there had been no sprinters who made an impact on the international stage. At the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona no British sprinters were even selected. And four years later, at Atlanta in 1996, it was the same again: no British sprinters were deemed good enough to go. It was, explained the British coach, Doug Dailey, simply a case of ‘quality control. They just weren’t fast enough.’

Speaking in 1997, Dailey admitted that the track sprinters had for several years been treated like outcasts. But, he explained, ‘That’s about to change now. There is real progress and my feeling is there’ll be a leading light who will drag sprinting along and set the standard other sprinters have to aspire to. This boy MacLean will set the standard and he can have a dramatic effect on sprinting.’ Sprinters tend to come in little groups – the Americans and Aussies have theirs. ‘MacLean,’ Dailey added confidently, ‘can become the Guv’nor.’