Читать книгу Heroes, Villains and Velodromes: Chris Hoy and Britain’s Track Cycling Revolution - Richard Moore - Страница 6

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

A Righteous Kick up the Arse

Palma de Mallorca, March 2007

The scent of drying concrete fills the air; scaffolding is everywhere; workmen go about their business with a sense of urgency, adding bits to the Palma de Mallorca Arena here, painting bits there. The impression is unmistakable, and not in the least encouraging. The 2007 Track Cycling World Championships begin here tomorrow, in a place that currently has the atmosphere, smell, appearance, sound, and ubiquitous dust, of an unfinished building.

However, deep in the centre of the arena, in what feels like its core, far from the madding construction, there is a rather surreal spectacle: a perfect oval of varnished wooden boards, glistening and shining as they reflect the bright spotlights – a bit like crashing through a waterfall and entering a peaceful, serene hideaway. In the case of the Palma Arena, the sight is that of a beautifully finished, brand new cycling track: 250 metres all the way round, with steep, wall-of-death-style banking at each end, sweeping into short straights, then quickly curling into the next banked bend.

And in this oval, burling around the bends, thundering along the brief straights, the British team, comprising eighteen riders – with twenty-eight support staff looking on – are going through their final training session before the championships. They are slick, organized and thoroughly impressive to watch; they also present a neat juxtaposition to the chaos outside, the only reminder of which is the occasional sound of a drill or some piece of machinery wafting in when a door opens.

But … hang on. Twenty-eight support staff to eighteen riders: did I hear that right? Are twenty-eight people really necessary? I suggest to Dave Brailsford, the British Cycling performance director, that this seems ‘a healthy ratio’. ‘It’s a winning ratio,’ smiles Brailsford, a man who manages, somehow, to appear simultaneously intense and relaxed as he watches his men and women whirl around the velodrome in a blur of red, white and blue.

I am here in particular to see one of Brailsford’s ‘blue-chip’ athletes, and a man regularly described as the ultimate athlete – the Olympic and world champion Chris Hoy. Chris and I were team-mates once. We were in the same Scotland team at the Commonwealth Games in Kuala Lumpur in 1998, but in many ways we belonged to different eras. For him, the Commonwealth Games were the start – they provided a springboard. For me, they were the end, the Commonwealth Games being as high as the bar of my ambition – I use the word advisedly – was set. In my case, a springboard with a malfunctioning spring – more like a trapdoor, really.

Back then, Hoy tended to be a little in the shadow of another rider, slightly older than him – Craig MacLean. The two of them came as a package: they were both blond, they were similar in appearance, they seemed inseparable and were constantly mistaken for each other. Craig used to sit in the apartment in the games village strumming his guitar. Chris didn’t play the guitar but he was, in other respects, Craig’s mini-me. There was something that set these two apart from the rest of the team, though. It was clear they were going places. The bar of their ambition was set fairly high; precisely how high, no one – not even them – could have imagined.

I was at those games, if I am honest, for the T-shirt (and three polo shirts, tracksuit, sweatshirt, shirt, tie, smart trousers, kilt and sporran, brogues, kit bag, racing and training kit … and yes, it says it all that I can reel that list off without really thinking about it).

‘That [Kuala Lumpur] Commonwealth Games,’ Hoy said to me on one occasion, ‘was the last games where the Scotland team had the attitude of being second-class citizens, and of thinking, “We’re gonna get humped here, but at least we’ve got the clothing.”’

Our team returned from these games, according to one report, ‘burdened by highly embarrassing statistics’. Which could be translated as: no medals. Again. Not that such humiliating return journeys were restricted to Scottish teams; at UK level, Britain’s cyclists repeatedly travelled to the Olympics, and returned – one or two notable exceptions notwithstanding – similarly ‘burdened by highly embarrassing statistics’. We were British: that was what we did. We got humped, as Hoy might put it.

Oh, but how times change. In Palma a new era is upon us – but more on Palma in a moment. This is the story of how that has happened: how the British team reinvented itself, and how Chris Hoy – who has been at the vanguard of this revolution, and is the central character in this story – is the embodiment of this new era in British cycling.

In one sense, Hoy was fortunate to find himself in the right place at the right time. In another, he is the perfect athlete to act as flag-bearer – because Hoy epitomizes all that is successful about British cycling. His finest hour up to that point was on a stifling hot evening in Athens in August 2004. The kilometre time trial at the Athens Olympics: Hoy’s event. As reigning world champion, he was last man to go – a mixed blessing. As he awaited his turn, he was forced to watch no fewer than three riders break the existing world record, knowing that he would have to step up and go faster than all of them – and faster, of course, than he had ever gone before.

Each new world record inevitably made Hoy’s task appear more and more difficult – impossible, even. Watching it unfold on TV, I found myself making excuses for him. Whatever happened in the next few minutes, he had done well to be crowned world champion. He, however, was not thinking along such lines. Finally, it was his turn to step up to the plate, as they say, and Hoy, looking like a man about to face the gallows – albeit clad in his unlikely ‘death suit’ of lycra – stood up, and walked awkwardly to the track in his cleated cycling shoes. And hurriedly, since a mistake with the timing device meant the countdown began early.

That technical glitch – possibly even more than the three world records he had just witnessed – was the moment when panic should have taken over. But if he was rattled, it didn’t show. Instead, he sat on the wooden boards, looking confident rather than pensive, while the mechanics fitted his bike into the starting gate. Then he climbed aboard, took several deep breaths, as if inflating his body down to his ankles, and settled forward, wrapping his fingers carefully around the handlebars, standing up on the pedals, waiting for the clock to finish its countdown. And when the last five seconds had cranked up the tension to an almost unbearable degree, he went off like a bomb, releasing enough power to illuminate a small village.

As Hoy started his ride, cheeks puffed out, legs pumping, I watched in a pub in Edinburgh, where the atmosphere was close to that of a football match. We roared at the TV, and when, after four laps, he flashed across the line in a world record time, we cheered, and I turned to a friend and said, ‘Did I mention that he and I were team mates …?’

Something else that happened in the build-up to Hoy’s ride in Athens was telling. While he was warming up, a medal presentation from another event got underway; but when it came to the national anthem, while many continued what they were doing, Hoy stopped, dismounted, and stood in respectful silence for the duration of the anthem, before remounting his bike and resuming his warm-up for the biggest race of his life.

Back to Palma. The stakes are high as we near the end of another four-year Olympic cycle and the 2008 Beijing games loom on the horizon. Hoy is in action on the first night of the world championships, in the team sprint, a thrilling three-man race that, like many of the track racing disciplines, can appear utterly bamboozling to the outsider. But it is actually very simple. In a nutshell: three men start, one finishes. Opening that nutshell and examining the contents: the trio line up together on the start line, side-by-side-by-side. On the opposite side of the track their opponents do the same. On the inside is the lead-out man, who rides the first lap flat out and then swings up the banking; next to him is the rider who, having followed an inch behind him on the first lap, will hit the front on lap two; and on the outside is the rider who will finish off the job, completing the third and final lap alone. For Team GB, the experienced – that sporting euphemism for ‘old’ – Craig MacLean is the lead-out man; the young pretender Ross Edgar is number two; the dependable Chris Hoy is the anchor. Hoy makes a comparison with athletics to explain their specific roles: ‘Man one needs the pure speed of a 100 m sprinter; man two has the speed and staying power of a 200 m specialist; man three needs the speed and endurance of a 400 m runner.’

The British trio qualifies fastest. It puts them into the final, against the French, where MacLean – billed as ‘the world’s fastest man over one lap’ – explodes out of the start gate, all popping eyes and pumping arms and then, after a lap, swings up the banking, allowing Edgar to come past, with Hoy remaining in Edgar’s slipstream. They are 0.290 seconds down on the French after a lap; Edgar reduces it to 0.281 after two, then swings up the banking as they approach the line. Hoy hits the front.

And now, not for the first time, we are treated to a head-to-head between Hoy and his old rival Arnaud Tournant. Hoy puts in a stunning lap, or perhaps Tournant slows down – it is difficult to tell. They are neck-and-neck on opposite sides of the track, and as they cross the line it is impossible for one pair of eyes to separate them.

The clock can, however. Just. The French have completed the three laps in 43.830 seconds – a world record; the British in 43.832 – also a world record, had the French not gone two-thousandths of a second quicker. So it’s silver for Hoy, Edgar and MacLean.

‘There wasn’t much else we could do,’ says MacLean. ‘But I’m sure when we look at the video we’ll pick a few things out. There’s always room for improvement.’ ‘Tonight the French were outstanding,’ adds Hoy, ‘but at least we got that ride out the way before Beijing. We’ll be better then.’

The following evening in Palma is the keirin, a discipline with its origins in Japan, where it forms a betting industry worth $7.5 billion a year; ‘kei’ means bet in Japanese, ‘rin’ means wheel. Many seem to be under the impression that ‘keirin’ means fight – which it doesn’t, though it would be fitting if it did.

The keirin is a sprinters’ event where six of them fall into line behind a motorcycle-mounted pacer, who over several laps gradually winds up the pace. There can be jostling for position, but generally the cyclists form an orderly line behind the motorcycle pacer and remain in order until, with two-and-a-half laps remaining, he swings off. Then, with the speed up to around 30 mph, it becomes a straight fight for the line, or as straight a fight as you can expect with six sprinters – who by definition are muscle-bound, (naturally produced) testosterone-fuelled alpha-males – competing with each other for the most advantageous position, which is generally held to be third or fourth man in line, where you have the benefit of shelter plus the advantage of surprise should you choose to launch an early attack.

But in Palma, Hoy doesn’t ride the keirin like this. He opts for a different tactic altogether. In the semi-final he tucks in behind the pacer, as first man in the string of six riders. When the pacer disappears Hoy stays there, ramping up the speed with deceptive ease, and effectively making it impossible for his opponents to come past him. His is a victory based on sheer power rather than tactical acumen.

In the other semi-final his team-mate Ross Edgar takes the opposite approach. With a lap to go he is last man, placed sixth and seemingly out of it. Yet, despite the fact they’re now travelling at around 40 mph, the compact, stocky Edgar manages an extraordinary surge, injecting enough speed to propel himself around the outside of the five flying bodies, to cross the line first. More of a pure sprinter than the powerful Hoy, Edgar has just demonstrated why, at twenty-four, he is tipped as one of the world’s hottest prospects. It is a performance that is destined to become a YouTube classic.

So to the final, and a fascinating contrast in styles – but it is not just about Hoy and Edgar. There are another four riders, most notably Theo Bos, the rapid Dutchman. Bos – or ‘The Boss’ – is the fastest man in the world, the undisputed king of the sprint – up to this championship, at least. Is he still the same awesome force? There are whispers and murmurs that he might not be – that chinks have been spotted in his previously impenetrable armour. Since being voted Holland’s sports personality of the year there are even rumours that fame might have gone to his head, that he might have been afflicted by the potentially fatal condition for a sportsman – that of believing that he really is as good as everybody is saying.

Thinking about Bos, and speculating about his form, I am reminded of something Dave Brailsford has told me. ‘We’ve banned the C-word,’ said the British performance director. ‘That’s something we insist on.’ But I wasn’t looking at Bos and thinking that he was the most offensive word in the English language. ‘Complacency’ Brailsford had elaborated. ‘We’ve banned it.’

As in his semi-final, Hoy tucks in behind the pacer. Bos sits behind Hoy. Edgar sits behind Bos. It is a good tactic: a British sandwich with a Dutch filling. When the pacer swings off, all hell breaks loose, as it always does in the keirin. As they hit 40 mph there is jostling, bumping, barging, but, as in the semi-final, Hoy appears quite serene at the head of affairs – all the frenetic stuff is happening behind him. Bos, try as he might, cannot quite find the strength or the speed to come round him: Hoy is too fast, too powerful. Holland’s golden boy and defending world champion crosses the line second, with, emerging from the melee behind, Edgar holding off the challenge of Mickaël Bourgain of France to claim bronze.

‘I had no pressure on me today,’ says Hoy, who couldn’t have been more imperious in winning the gold medal, but for whom it was, nevertheless, an unexpected bonus. ‘Jan [van Eijden, the GB sprint coach] told me to relax, and in the final I used my kilo strength to lead out from a long way. It couldn’t have gone any better. But it’s a big surprise.’

And still to come, on the final night of the championships, is Hoy’s main event – the kilo, in which he is Olympic champion, three-time world champion and sea-level world record holder. In six weeks, at the altitude of La Paz in Bolivia, he will go for the absolute world kilometre record, currently held by his great rival Tournant.

As reigning world champion, Hoy is once again the last man to go. The kilo – he insists this will be the last time he will contest this event in a major championship – also gives him the chance to draw level with the two kilo kings, both of whom have four world titles to their name. Ahead of him in the table are Lothar Thoms and – who else? – Tournant.

Another British rider, Jamie Staff, the second man to start, is the early pacesetter. He tops the leader board for the best part of an hour, until the penultimate rider – another Frenchman, the youthful François Pervis. In Manchester, just a few weeks earlier, Pervis placed second to Hoy in the World Cup kilo – and gave him a real fright in finishing just thirty-five-thousandths of a second slower. Now, in Palma, it all comes down to Hoy and the clock. He races through the first of the four laps marginally up on Pervis, but down on the time set by fast starter Staff. Hoy has to lift it and he does; at half distance he is a tenth of a second ahead but it is in the second half that he makes the difference, accelerating to cross the line in 1.00.999, almost a full second quicker than Pervis. It is Hoy’s second fastest kilo and the second fastest time ever recorded at sea level.

It puts the icing on a generous cake: the championships have been an astonishing success for Hoy and for Team GB. In fact, Hoy’s haul here in Palma means that he is now the most successful British cyclist of all time in terms of gold medals won at world championships, with seven golds, one silver, three bronze, to add to Olympic gold and silver, not to mention two golds and two bronzes at the Commonwealth Games He can now be hailed as Britain’s most successful track cyclist ever. The debate over whether he is the best ever can rage in internet chat rooms.

Yet there is a sour taste in his mouth. It had been his final championship kilo, but not out of choice. The decision had been effectively forced on him by cycling’s world governing body, the UCI, who, in an act as bizarre as it seemed perverse, responded to the most exciting kilo of all time – at the Athens Olympics in 2004 – by dropping the event from the Olympic programme.

‘I’d love to do the kilo at the world championships in Manchester next year and go for a fifth title,’ Hoy tells the press in Palma, ‘and obviously I’d have loved to go to Beijing and defend my Olympic title, but I really have to draw a line under this event now and focus on an Olympic event. But it’s frustrating because I don’t think the powers-that-be really understand certain facets of the sport. I don’t think they realize the implications of what they’ve done.’

The challenge now for Hoy is to try his hand at new disciplines – the sprint and the keirin. His surprise victory in the keirin in Palma gives him confidence but Hoy is under no illusions: he knows he has much to learn. He also knows that, at thirty-one, he doesn’t have much time. He is a (comparatively) old dog having to learn new tricks if he is to have any chance at all of fulfilling his ambition of a second Olympic gold medal. Imagine Michael Johnson, at his peak, being told the 400 m was being scrapped; or Ed Moses being told to switch to flat racing. This is the scenario Hoy has been presented with thanks to the scrapping of the kilo. The next twelve months will tell him if such a transition is possible – he is acutely aware that it might not be.

But otherwise the taste in Palma is of sweet success. ‘Being here at the world championships with the British team has been great,’ says Hoy after his kilo victory. ‘We’re really unified. There are no cliques, no divides. We go into every event thinking we can win medals. We have a winning mentality.’

As he is talking, the opening bars of ‘God Save the Queen’ fill the Palma Arena (again), and Brailsford can be seen deep in conversation with a member of his four-strong senior management team – Britain’s 1992 Olympic pursuit champion Chris Boardman. Both are standing with their arms crossed. They uncross them and cease their conversation for the national anthem, then immediately recross their arms and renew the discussion. It looks like they’re plotting something.

They are. But eventually they part and Brailsford offers a review of the championships. Or, rather, he doesn’t. Instead, he looks forward. ‘Tomorrow,’ he says, ‘I will be at my desk in the Manchester Velodrome, relentlessly planning our pursuit of medals in Beijing.’

In the final reckoning, the British team has claimed eleven medals in Palma, including seven gold: 41 per cent of all the available world titles. The other squads retreat from the arena licking their wounds. ‘We’ve just had a righteous kick up the arse,’ admits the Australian coach, Martin Barras. ‘That was the best performance by a track team, period,’ he elaborates. ‘It’s as simple as that. And Chris? What can you say? His win in the keirin was something else, and I’d put his kilo here in Palma above his performance at the Olympics. It was phenomenal. As a professional coach, never mind the coach of a rival team, you just have to go: “Wow.”’

Brailsford can well afford to be satisfied, then. The Olympics are the overriding goal, as he keeps stressing, but with every medal his stock – and that of the British team – rises. The unprecedented success in Palma means it has never been higher, and it was already pretty high before Palma, when it was reported that various performance directors from other sports had been beating a path to his door, to pick his brains and learn from Britain’s most successful team. Apparently, the people charged with running athletics, rugby and rowing had all been to visit Brailsford in recent weeks. Brailsford is coy on this.

In talking to Brailsford, however, there is one subject that looms ominously and lurks malevolently in the shadows. This being cycling, there has been a gathering cloud of suspicion, rumour and innuendo, whispered in the past, but inevitably set to be more explicitly stated the more successful they become. In the Italian camp there have been accusations that the secret to the British team’s success must be doping – organized, systematic doping.

When asked about this, Brailsford doesn’t sigh in exasperation. He doesn’t fix you with a withering stare. He doesn’t point out that it is impossible to prove a negative. In short, he doesn’t dodge the subject. And what he says, though it may look almost naive, contains an irresistible logic. ‘We create an environment in which athletes don’t want to dope,’ he says. Ah. Okay, then. But how? ‘Come and have a look at what we do,’ shrugs Brailsford. ‘We have nothing to hide. We look at aspects of performance that have nothing to do with doping. But anyone who wants to check us out can come and have a look at our anti-doping programme and draw their own conclusions.’

But if it isn’t a highly sophisticated and organized doping programme, then what is the secret? Is there one? Still hanging around the track centre is Boardman, whose remit, as director of coaching, includes ‘research and development’. The man who was once famous for winning the Olympics on a machine christened ‘Superbike’ is now – appropriately enough – charged with sourcing and developing the latest, most cutting edge equipment, from clothing to bikes. Boardman is leaning over one of the barriers that segregate the teams, in their ‘pens’, when I approach him. He looks furtive. Nothing to hide, eh? Yeah, right – not according to Boardman. While Brailsford stresses that the anti-doping programme is open for inspection, Boardman makes it clear that the equipment bunker – the ‘Secret Squirrel Club’ he calls it – is strictly off-limits. So the implication is clear. Effectively, what they seem to be saying is: ‘You can come and watch our athletes piss into a bottle; just don’t ask them about the fancy saddles they use in training.’

‘We have kit we’ve been using in training but we haven’t used it here,’ confirms Boardman. ‘We produced some really sexy handlebars for the sprinters last year, but at last year’s world championships the Germans came along and took some pictures of our handlebars, and now they’ve got them.’ It is easy to see how this could happen. At a track meeting, where the teams occupy their pens in the centre, separated from each other only by metal fencing, equipment is easily visible. All kinds of people are sniffing around. And some, says Boardman, are spies. ‘If you leave stuff lying around the track centre,’ he points out, ‘then people will see it.’ It is fairly important, then, to keep the top Secret Squirrel ‘stuff’ hidden – and note, incidentally, the deliberately frivolous, almost Orwellian sounding, moniker assigned to Boardman’s ‘club’. ‘We’re paying a lot of money to develop this stuff,’ he points out, ‘so next year we’ll use it in competition, but it’ll be too late for anybody to copy.

‘And a lot of it you won’t even be able to see,’ he adds, looking satisfied. As well he might. He knows that, if nothing else, such talk will score points in the psychological war. Consider this: if it is frustrating for the opposition to look enviously at the state-of-the-art machines belonging to their rivals, then how frustrating must it be to know that you can’t even see half of what makes it state-of-the-art? It is the sporting equivalent of Donald Rumsfeld’s infamous ‘known unknowns’ argument. ‘There are known knowns,’ said the then US secretary of state for defense, speaking of the War on Terror. ‘Then there are known unknowns. But there are also unknown unknowns.’ Some of the stuff in Boardman’s Secret Squirrel Club comes into this category. As far as the opposition is concerned, it is an unknown unknown. How much of a mind-fuck is that?

This, mind you, is a game that goes on between all the teams, with psychological warfare a big part of track cycling for all kinds of reasons – the riders rub shoulders in the track centre, they warm up in full view of each other, the racing itself is gladiatorial; there are no hiding places; image and appearance is (almost) everything. Boardman doesn’t criticize other teams for ‘sniffing around.’ Far from it.

‘Oh, we do it,’ he says. ‘I don’t do it myself, because that would be too obvious. I have somebody doing it for me, and I can assure you they’re not wearing a GB T-shirt. I heard about one bike manufacturer sending guys who looked like cycling groupies in long hair and long shorts. They’d look daft and ask stupid questions and the mechanics would just stand there and tell them everything.’ Boardman shakes his head. ‘You have to be clever.’

What is remarkable about all of this – the confidence, the gold medals, the ample resources, the subterfuge, the aura of invincibility, the sheer ebullience – is that this is a British team we’re talking about. A British cycling team. Ten years ago British cycling teams were the designated whipping boys, and girls: that was their role. To other nations it must have seemed their raison d’etre. Yet now it is they who do the whipping, kicking the collective arse of the once dominant Australians. The Australians!

To fully understand how far the British track cycling team has come you must first understand where it was. It was nowhere. Over the decades there have been exceptions – outstanding individuals such as Reg Harris, Beryl Burton, Hugh Porter, Graeme Obree and indeed Boardman himself – but each succeeded despite the system, not because of it. Because there was no system.

In 1997, when Hoy began to be a regular member of the British team, he was given a racing outfit, ‘told to feel grateful for it’, and lent a bike, ‘a state-of-the-art bike – from the 1960s’, and told to feel grateful for that, too. In 1996, when he was selected for his first international event – the European Under-23 championships in Moscow – he was one of three riders, with no support staff. They could only afford to send three people, so they decided not to bother with a mechanic or a team manager. Compare and contrast that to the twenty-eight support staff in Palma.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of what has happened over the last decade – the development of a system every bit as efficient and effective as the old East German system, without the systematic doping – is that it just seems so unBritish. We don’t really do success – or not systematic success, at any rate. According to the December 2007 issue of the Observer Sports Monthly magazine, we are, in fact, ‘ritually accustomed to defeat’. According to Simon Barnes of The Times, we ‘have no contingency plan for excellence, no strategy for dealing with the calamity of victory’. When we win, we go off the rails. Whatever it takes to build on success, or even sustain it, we just don’t seem to possess it.

That Observer article (entitled ‘Born to Lose’) concluded by claiming that is not that we do not want to win: ‘We want to win as much if not more than anyone else. We just do not want to do what is necessary to win.’ We do not want to do what is necessary to win. Which raises the question: what is necessary to win? Well, if anyone knows the answer to this question it is Chris Hoy. And the British cycling team. How has this happened? And why in track cycling?

What struck me in Palma, as the British team dominated event after event, and my old – ahem – team-mate Chris Hoy confirmed himself as one of the all-time greats, was the realization that there was something – beyond winning – that was very special, and very unusual, about this team. There was planning, and attention to detail, and athletic talent – all these things, of course. But there was something else – a unique and very potent chemistry. And there were secrets – intriguing, closely-guarded secrets, from Boardman’s Secret Squirrel Club to the team’s employment of a clinical psychiatrist – someone whose previous work had been with inmates of a high-security hospital, but who, in 2002, had made the surprise career switch to work with Britain’s top cyclists. The success of his work with certain members of the team prompts Brailsford to say that he is ‘the best person I’ve hired – and I’ve hired some great people’.

Sporting success, skulduggery, psychiatry, suspicions of systematic doping, in a world of heroes, villains and velodromes … there could be a hell of a story here, I thought.

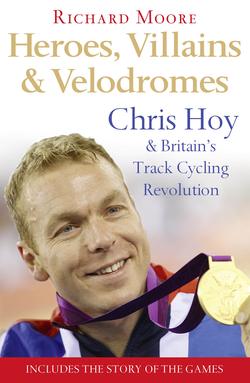

A couple of weeks after Palma, a month before he was to travel to Bolivia to try and set a new world kilometre record, I sat down with Hoy in a bar in Edinburgh and gave him my spiel: ‘I’d like to write a book – about you, and about this incredible year you have in front of you, taking in Bolivia, the World Cups, the crazy keirin circuit in Japan, the madness of six-day racing, the world championships in Manchester … and looking ahead to Beijing. Only, it won’t really be about you, as such, well it will, and it won’t – it’ll be part your story, your BMX-ing as a kid, that sort of thing, but it’ll also be the story of the British team – the revolution there’s been over the last ten years. I mean, it’s an incredible story, really, when you think about it … what do you think?

‘Okay,’ said Hoy.