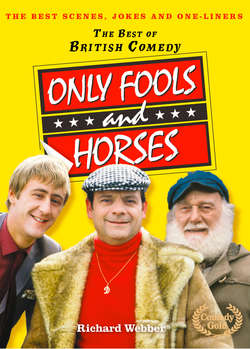

Читать книгу Only Fools and Horses - Richard Webber - Страница 6

THE STORY IN A NUTSHELL

ОглавлениеWriter John Sullivan had already scored with a hit sitcom, in the shape of Citizen Smith, by the time he turned his attention to Only Fools and Horses.

The then BBC head of entertainment, Jimmy Gilbert, had played a key role in launching Sullivan’s writing career by commissioning Citizen Smith and was keen to retain the services of the talented writer. Although he wasn’t enamoured of the title, Only Fools and Horses, he knew immediately that the sitcom’s premise – a London family who wouldn’t sponge off the state as they wheeled and dealed their way through life from one dubious business deal to the next – would work.

The first series was eventually commissioned, centred on the Trotter family, a surname Sullivan had encountered previously, having worked with someone of the same name. Experienced director Ray Butt took control of the opening season before passing the reins on to Gareth Gwenlan.

When it came to casting, Nicholas Lyndhurst was already in the frame to play Rodney, a decision which pleased Sullivan. Finding his older brother was trickier. Enn Reitel and Jim Broadbent were both considered before David Jason’s name entered the frame. By chance, director Ray Butt watched a repeat of Open All Hours, with Jason playing Granville, and knew instantly that he’d found his man.

Did you know?

Only Fools and Horses was originally titled Readies. The name was eventually changed to the former, which had previously been used for an episode of Citizen Smith.

With Lennard Pearce recruited to play Grandad, the opening series kicked off with the episode ‘Big Brother’ on 8 September 1981. The six episodes comprising the first season didn’t set the world alight in terms of audience figures, attracting just under eight million viewers. But this was the era where new programmes were given time to find their feet in the over-subscribed world of TV.

Del had no sense of style.

© Radio Times

Rodney always felt he lived in his brother’s shadow.

© Radio Times

Great writing and sublime acting were the fundamentals behind the success that followed; regarding the latter, the adroit casting which paired David Jason with Nicholas Lyndhurst couldn’t have been more profitable. Jason’s animated and overt portrayal of the older brother was juxtaposed by Lyndhurst’s beautifully crafted interpretation of the languid younger Trotter.

Initially, John Sullivan didn’t think the BBC were keen on the sitcom and half-expected it to be scrapped after the first season; he was, therefore, delighted when asked to pen a second series, although the average audience figures, just under nine million, were far from ideal. It wasn’t until Series Four, which saw viewing numbers average above 14 million, that the show had found its footing. Sadly, though, the growing success paled into insignificance when the death of Lennard Pearce, alias Grandad, was announced. John Sullivan et al were left with a dilemma: how to bridge the almighty chasm left behind by Pearce’s sudden death. Recasting was out of the question, so John – while meeting with Ray Butt and Gareth Gwenlan – suggested introducing Albert, Grandad’s brother, to add an extra dimension. After frantic rewriting of the scripts, Uncle Albert made his first appearance attending his brother’s funeral in ‘Strained Relations’. Buster Merryfield, a bank manager turned actor, was welcomed into the fold and delivered a sterling job under difficult circumstances.

By the time Series Six was screened, the episodes had been extended to 50 minutes and Only Fools and Horses had established itself as arguably the BBC’s most popular programme. Extended episodes proved beneficial in many respects, including John Sullivan not having to cut funny scenes purely to reduce the length of the script and affording him the opportunity and time to explore his characters and storylines in more depth.

‘OH THE EXTERMINATOR. WELL, OF COURSE, TO RODDERS THAT IS ROMANTIC. I MEAN, HE CRIED HIS LITTLE EYES OUT OVER THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE.’ (DEL)

In the latter stages of the sitcom, we saw the Trotter brothers finally settle down and take on life’s responsibilities more willingly. In due course, Del and Rodney discovered true love in the shape of Raquel – who was only expected to appear in one episode but made such an impact the character was retained – and Cassandra respectively, and, later, fatherhood. The Trotter brothers were maturing, settling down and discarding their lads-about-town image.

Although the boys’ marriages suffered more than their fair share of ups and downs, again providing John Sullivan with the chance to exploit his skills of writing the poignant moments, the series had moved on to a more mature level.

All good things must come to an end, though, and the screening of the 1996 Christmas Trilogy marked the cessation of visits to the Trotter household – or so everybody thought. If this had been the end, the show certainly went out with a bang. Each of the three episodes were watched by over 20 million viewers with the final instalment, ‘Time On Our Hands’, with the Trotters finally becoming millionaires, pulling in a colossal 24.3 million viewers, all glued to their screens to bid farewell to Del, Rodney, Uncle Albert and the rest of the gang. As always, the episodes had successfully mixed pathos with humour, and it was clear the British public were going to miss catching up with the frustrating yet loveable Trotter boys.

When the brothers struck gold, it looked like the lights would be switched off at Nelson Mandela House for good. No one intended making more episodes, but in the world of TV you never say never. One day, a throwaway comment from Gareth Gwenlan, hinting that perhaps a special episode would be made to celebrate the new millennium, started the ball rolling and, eventually, they were back.

Turning his attention to the scripts, Sullivan knew that keeping the Trotters as multi-millionaires wouldn’t have worked. If they were to stroll the streets of Peckham once again, he wanted to return them to where they started; the trouble was, he couldn’t do that in one episode. Eventually, another trilogy was commissioned.

John Sullivan decided the Trotters would lose their fortune, thanks to Del gambling away their millions on the Central American money market, and so five years after the final instalment in the Christmas Trilogy, the crowd were back.

The three episodes, ‘If They Could See Us Now …!’, ‘Strangers On The Shore’ and ‘Sleepless In Peckham’ – and this time they would be the last – were transmitted on Christmas Day 2001, 2002 and 2003. There were times when Sullivan regretted writing the new shows because the press reaction was disappointing, despite winning plaudits from the audiences. Later, though, John was able to appreciate the episodes which, again, proved that quality writing, casting and acting win every time.