Читать книгу Last Chance Texaco - Rickie Lee Jones - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

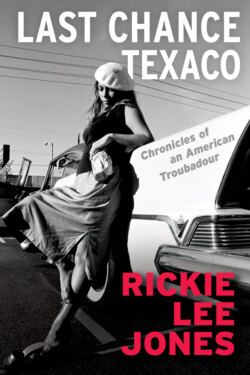

ОглавлениеChapter 4

A Summer Song

Father, Janet, Danny, Mother (pregnant with Pamela), and little Rickie Lee, 1963

My baby sister was born five or six weeks early. Premature Pamela went from Mother to the intensive care unit and stayed there for weeks. When she finally came home, she had an embryonic serenity but she was such a tiny creature that she seemed too small to be a human infant. A blanket of fuzzy hair covered her body but no eyelashes or fingernails and even her crying was faint. She sounded like a faraway lamb.

Those afternoons with my newborn sister, I lay with her on Mom’s bed, petting the chenille bedspread with my feet. What a mystery she was. I laid my baby doll next to my sister. “Remember this,” my mother said, “your doll is bigger than your baby sister. One day you won’t believe it was possible.”

In the languid light of the Venetian blinds, I performed improvised operas, epic melodies of my own design. I was a mommy, singing to her, rocking her, loving her so.

I was about to enter the transitory and terribly uncomfortable age of ten. This passage to adolescence is ripe for rock bands and pop stars. Young girls are suspended in time as they fall deeply in love with the larger world. I was to fall for the first and best of all of them, the Beatles, and they would remain my true love, musically at least, for the rest of my life.

Our new house on 32nd Avenue was about a mile from our old one, next door to a car wash. We had apricot trees, two rabbits, and a stereophonic console record player. When I wasn’t standing by the back window trying to practice my violin, I lay in front of the record player and listened to my dad’s records: Andy Williams’s “Moon River,” Nina Simone’s “Black Is the Color,” and my favorite, Harry Belafonte’s Calypso. I was studying music theory and I did not even know it.

Just a month or so after we arrived in our new house, my six cousins and Aunt Linda arrived from Chicago. With Uncle Bud gone, Linda wasn’t able to look after all six children. Uncle Richard might be a surrogate father, they hoped, but my father was the rebel artist of the family and barely involved with his own kids, much less six more. It was the summer of 1965.

I was thrilled to meet my new instant family of so many children. Cousins by the dozens! They were all Chicago attitude, thick accents smearing a “y” on the “a,” so tough and mean. The girls ratted their hair and drew black eye-liner under their eyes. That summer they taught me to dirty dance.

Uncle Bud had been a prolific man, child-wise. He was the handsome oldest brother. I have only one memory of him, a memory of safety and love, the kind of memory upon which the others lean.

Uncle Bud often babysat his brother’s three-year-old girl—me. Bud lived in an old wooden Chicago tenement apartment, one story up. On this day, as Mother was sneaking off to work, I just caught her leaving—the edge of her coat slipping out the room. I screamed and I ran to the screen door as it sprung back and slammed my finger. I stood there, wrecked in despair and pain, crying as the bus drove away. Don’t leave me here Mother! Don’t go!

My Uncle Bud bent over and picked me up. He turned and sat down in the rocking chair in front of the round black-and-white television screen. There he rocked me, back and forth, back and forth, holding me tight, until no more sobs hiccupped from my chest. This memory of being comforted by my uncle trumps all infant memories. I am sure we were cared for, but this is the only memory of love and consolation that made it out of Chicago.

“The heart is always that one summer night . . .”

My cousins’ new house was on a corner where neighborhood kids came out at night to play. It was the best August I would ever know, even better than the end of summer after my debut record came out. It was the best August of all time.

After our dinners of Rice-A-Roni and fried chicken when the heat went down to ninety degrees, my cousins and I would emerge from our houses to join the other hungry desert animals in the coolness of the night. We played all-neighborhood games like kick-the-can and hide-and-go-seek. My mother was reluctant to allow me to play with “the gang.” We might be related to these Joneses but they were not like us and she did not want me becoming like them. I’d already heard swear words from them I had never heard before, much less coming out of the mouth of a six-year-old.

The thing about a game like hide-and-go-seek is that if you are really good at it, then no one ever captures you. A girl has to pretend not to be very good if she wants to make friends. I was so determined to be good at everything I did that I was rarely captured. It was discouraging.

One night it was only Rodney and Debbie and Donna and I. We were ants-in-our-pants anxious to live out every summer night before school started.

“Where are you going?” Mother asked.

“Out.”

“What are you doing?”

“Nothing.”

“Be back here in forty-five minutes. I mean it.”

Three cousins and I walked down the sidewalk. This was our sidewalk.

“So what are we doing?” I asked.

“We are going to ring doorbells.”

“Huh?”

“We ring the doorbell and run.”

“Some adult opens the door and no one is there.”

“It’s funny but scary because they get mad and can catch you.”

It sounded so frightening that my stomach felt queasy. I was going to do something bad! Something Mother would not approve of, but I’d be part of the gang. We snuck up to a house and rang the doorbell. The interior light spilled out the front door and a man followed. Ha! He’s so big and we lured him out of his house! He can’t see us. We win! Ha ha hah! We conquered the adult in his own domain.

Not a nice game but we didn’t realize that someone might really be afraid.

As the night wore on, it got quieter and spookier. The shadows were blending into the darkness and no cars were going by. It was my turn to ring the doorbell. We chose a house, crept up to it, and then everyone hid as I approached the door. I was alone crossing the last few feet to the doormat. I still remember the columns on the porch. Even the crickets stopped singing.

I rang the bell and bam! No porch light, no shuffling of feet—it was like he was waiting for us. There was no time to jump off the porch, no chance to run. In the microseconds of the door starting to open I had only one option. I stepped next to a column on the porch.

My cousins could see me standing on the street side of this column as the man walked out of his house. He looked aggravated. I could see his face in the streetlight.

Behind my pillar I held my breath. I willed, I prayed to be invisible. “Don’t see me, don’t see me, don’t see me.” I was standing four feet away from him when he looked right at me. He seemed to be looking right through me. It was true, he could not see me! I was invisible!

The man moved toward me now to stand on the opposite side of the pillar. I almost said, “Hi. I’m here. Fooled ya!” But no, I kept my breath in and stayed so very still. I could see my cousin Debbie’s eyes were wide as saucers and she was motioning me to not move.

Then he simply turned and went back into his house. The sound of the screen door slapping its wooden frame was my cue: I jumped onto the grass and ran to my cousins who emerged from the shadows of cars, telephone poles, and shrubs. We ran halfway down the block toward Aunt Linda’s, squealing with excitement.

“He looked right at you!”

“Yeah! Did you see him do that?”

“Impossible!”

“Like you were invisible.”

“Oh my God!”

“I was invisible!”

Something told me that he had not been able to see me there in the shadows for two reasons. One, he didn’t expect me there, and two, because I had willed myself into a different reality and it had worked. Real magic. Adult-tested invisibility. That night I became invisible using the airless spirit of night that hides what does not want to be seen.

Every school year my mother bought me and my brother Danny a whole new wardrobe. I received new blouses, skirts, dresses, shoes, the whole treatment. This year Mother decided to make our clothes and cut my hair herself. My bangs were crooked in my school picture that year and I could not tell her that all I wanted was store-bought clothes and to be like everyone else at school.

After school Mama would ask, “Did anyone say you looked pretty today?” This was her way of saying, “You are pretty if someone tells you that you’re pretty.” She wanted people to accept me and be kind to me, but she was also asking whether I had been accepted. Her questions never made things better. Not even when the answer was yes and she was happy for me. Her constant need for people’s approval made my private moments of anguish into a family announcement of my failures.

Perhaps because school was a closed door to me, I found beautiful places inside myself. I dwelled on things most people didn’t even see. I kept myself intact and part of everything around me by daydreaming.

Someday, I promised myself, I would be a beautiful lady on television accepting an award of my own. An Oscar! Miss America! I would be so beautiful, and all those kids who drew cootie lines around me would wish they could be my friend. I would create a whole wide world from my own imagination. I would teach it how to find magic. Maybe I would find others like myself.

Those long daydreams often ended up on my report card. “Rickie daydreams all day long”—as if that were a bad thing. I had a highly active imagination with nowhere to grow. This year there would be no daydreaming, not in Mr. Carter’s class.

“When they know you’re not watching they talk behind your back”

My fifth grade teacher was a small, square-shaped bully with a crew cut and a bad temper. He once manhandled me by my collar because I told my classmates, “Drop your pencils at four o’clock.” With my stunt, I finally made it onto their social radar screen. Listen: everyone was dropping their pencils because of me! They liked me!

Uh-oh. Outside the classroom, Mr. Carter picked me up by the collar and held me against the wall. He was threatening me with a fury that almost made me pee.

“Please Mr. Carter, don’t hit me,” I pleaded. The door to the classroom next to mine was open so the entire fourth grade heard me reduced to begging. It was humiliating. I was a fifth grader that even the fourth graders looked down upon. Mr. Carter didn’t care about a ten-year-old girl trying to get a little social footing. There is something fundamentally wrong in an adult man’s physical retribution when his feeble sense of authority has been challenged by falling pencils.

I wished I would die rather than have to stay at that school. I could not figure out what was wrong with me.

There was a ray of hope when I met my very first schoolyard friend, Susan Carl. She was a sassy girl with long brown wavy hair and a sweet face. She and her mother were from Las Vegas. Her mom wore too much makeup and ratted her hair up high. Susan and I bonded over being the first girls to get brassieres, which meant we were the first young girls of our class to be recognized as little women.

The first bra ritual was a big deal. For once in my life I did not feel like the outcast new kid. My nemesis, Jo Ellen Hassle, was no longer a threat. None of them were. Womanhood trumped any playground game as far as I was concerned. A maturing body was something far more substantial than winning a tetherball game. My little bra, along with Susan’s friendship, restored a modicum of dignity, just enough to get through the rest of the year.

Friends are passengers on the short flights from one place to another, and few of them manage the transition of families moving. When the sixth grade came, Susan and her mother moved back to Las Vegas. We promised to write and visit forever but we didn’t.

The Beatles

I first saw the Beatles in February 1964. My cousins and I gathered around the black-and-white television in Aunt Linda’s living room. The Rice-A-Roni was cooking on the stove and fried chicken was in the pan.

The Beatles were on The Ed Sullivan Show. With the rest of America we had waded through his usual muddy dis-entertainment of puppets and chorus girls, and now we finally got to see what this Beatles fuss was about.

What was that they were doing with their hair? Why was their hair so long?

Girls were screaming back there in New York City. A wave ran through the audience and out of our television screen. By the second bridge—“Well my heart went boom”—we were captured, defeated, and the world was remade in their image. We were not who we had been three minutes before. The entire country had the air knocked out of it. Nothing that has happened in entertainment since can compare.

The violin I was once so eager to learn suddenly seemed unnecessary. Square. Ever since Mr. Ellis put me in the second chair of the orchestra where I faked my way through performances, I knew I was never going to make it, not reading music as well as the other kids.

On the other hand, I learned every note of every Beatles song I heard. I understood this music instinctually and thoroughly. I sang harmony and matched every nuance of their recordings. I imitated, I improvised, I learned.

By summer, I had a Beatle haircut, Beatle boots, and Ringo rings. I collected Beatle trading cards that came with sheets of bubble gum, baseball cards for Beatle fans. If I could not have Paul, I would be Paul. In a life as unpredictable as mine, the Beatles gave me something I could depend on. In a world where my family might move any day, John and Paul gave me harmony that I could be part of.

Unlike other girls my age, I didn’t want to be a girl singer or the Beatles’ girlfriend. I wanted to be a Beatle. I was not afraid to be “the boy” if that’s what it took to find a little glory. I would find a way to learn guitar. When I first had access to one a year later, in 1965, I played it left-handed like Paul. Then I understood that the strings were backwards, so I reluctantly turned the guitar right side up. That certainly helped me with the chords, oh yeah.

Now I discovered the jukebox, the one that had always been there, and grubbed a dime or a quarter to play “Louie Louie,” mythic in its reputation as the most forbidden song, indecipherable in its pronunciation.

Or “Do Wah Diddy Diddy,” the song of 1965. As my cousins and I snapped our fingers and shoved up our feet, American rock stepped close behind. We were “Dancing in the Street” . . . from Chicago to L.A. “Hang on Sloopy” still makes my toes curl up. Fronted by Rick Derringer, the McCoys jettisoned little girls out of the cold wet Liverpool cavern and right smack in the back seat of a ’57 Chevy.

It was nasty American rock ’n’ roll. If you wanted to see how vulnerable our teen boys were, listen no further than “Rag Doll” on the East Coast and “Don’t Worry Baby” on the West Coast. Teen emotion was exploding like acne upon the surface of American culture, and there I was, right in the epicenter. Wherever there was a jukebox, there was a connection to the larger world. The songs never got old—we were building rock ’n’ roll.

It would be easy to dismiss the laments of surfers and their cars except that Brian Wilson’s melodies insisted, carefully, that we take notice. This was every kid’s lament—“I guess I should’ve kept my mouth shut”—but it was incongruous with the gentle melody it was nailed to. We felt it. The Beach Boys made it alright to do a little James Dean as you hung five and then “hahahahaaaa, wipe out.” Our American identity asserted and defined itself in the musical conversation taking place with the world. Or at least with Britain. Every song gave birth to another direction.

I was undergoing a social and spiritual metamorphosis. Rock music was my bible. Mine would be the first generation to make rock ’n’ roll both a lifestyle and a political movement.

My parents continued to strive for their American dream. That summer I had become an AAU swimmer. Mom and Dad told me that I had to take swimming seriously if I wanted to be the best. I committed, I was going to make it to the Olympics. They committed too. By August, I was fast at butterfly, I could easily glide up and over the water. I would press forward when others tired and I would win long-distance races. I loved to win and here I didn’t need others in order to feel good about myself; I alone was creating approval and accomplishments.

Mother woke me up at five in the morning to practice and after school I swam laps until dinnertime. My coach, Moonie, was an old Filipino who’d been to the Olympics for his country. He was rough and inspiring, tapping me in the water with a pole if my stroke faltered and stepping on my hands if I grabbed the side of the pool instead of flipping. “Ricarda! What are you doing?”

I started school looking sharp in my Carnaby Street fashions, sporting new clothes and feeling proud of myself from the ribbons and applause of swimming and my musical summer, but Orangewood School was a kiln, an oven of sorrow, and nothing I did outside of it ever took the heat off me. I simply could not find acceptance at school. It was so ridiculous that even the brother of one of Danny’s friends, who was walking near me one day said:

“I would walk with you Rickie, but the other kids don’t like you. You know how the kids are.”

“I know, that’s okay.” But it wasn’t okay. It hurt.

The difference between this year and last was that I could go home and listen to the Beatles. Finally, I had something real to hold onto, something that would hug me back.