Читать книгу Last Chance Texaco - Rickie Lee Jones - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

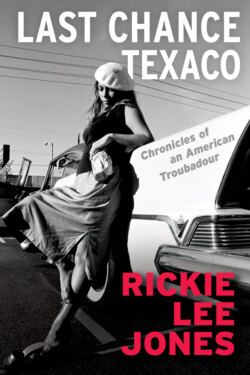

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION: A PRELUDE TO GRAVITY

Inamed this book “Last Chance Texaco” because I spent most of my life in cars, vans, and buses. Back seats, shotgun, and driving myself. From these vantage points I watched life approach and recede. As time went by I was always running away from and moving to new life, but once I finally got there I could never lay down roots. For me, it seems, life is the vehicle and not the destination.

The meaning of “Last Chance Texaco” is simple. It is the light in the distance that never goes out, refuge for the tired traveler on a dark road. “You can trust your car to the man who wears the star” sang the old commercial—an important backstory people today may not know—“The big bright Texaco star!” I used the familiar signposts and lingo of my generation to build the lyrics of “Texaco,” and in fact most of my early songs make reference to obscure Americana nearly forgotten today. When my young life seemed to be nose-diving into the desert sands of Hollywood, going nowhere fast, I raised that Texaco star like a pirate flag and overtook my future against all odds. The man with the star is as much Christ as he is a lover or a stranger in a gas station, whomever it is you need to put your trust in tonight. “Last Chance Texaco” remains a kind of living spirit to me. A whisper of belief in impossibilities.

When I was twenty-three years old I drove around L.A. with Tom Waits. We’d cruise along Highway 1 in his new 1963 Thunderbird. With my blonde hair flying out the window and both of us sweating in the summer sun, the alcohol seeped from our pores and the sex smell still soaked our clothes and our hair. We liked our smell. We did not bathe as often as we might have. We were in love and I for one was not interested in washing any of that off. By the end of summer we were exchanging song ideas. We were also exchanging something deeper. Each other.

Tom had two tattoos on his bicep. He liked to don the vintage accoutrements of masculinity: sailor hats and Bernardo’s pointed shoes. The more he tried to conceal his tenderness, the more he revealed a chafed and childlike nature. I adored him. He was my king. In bed he was the greatest performing lion in the world. I mean to say that Tom was never not performing.

Then quite suddenly, in November we were no longer seeing each other.

I spent the fall driving around with Lowell George, the charismatic guitarist from Little Feat, a local hero who kept his little feet “in the street” as it were. He found me there in my squalid basement encampment and we went drivin’ around in his Range Rover, seated high above the street studying various motels and apartments where he had spent time with Linda and Valerie and Bonnie too. He showed me the hotel I would live in one day—the Chateau Marmont—and we sat in the living rooms of managers who would load him up with drugs for the chance to put his signature on paper. He flirted with them all like a child flirts with the devil, toying with their furious drugged-up machinations and escaping, like a child called home by his mother, just before he signed his soul away. Lowell seemed unconcerned about his own mortality. The play was the thing, and that boy could play the guitar.

In bed Lowell was a fat man in a bathtub. I mean to say that something about him was in another room, laughing, singing to himself. He was a handsome man, unhealthy, kind to a fault.

By June we did not speak much anymore. He’d tried to obtain the publishing rights to “Easy Money” and Warner Brothers intervened. It left a very bad taste on both our tongues. I learned that lesson out of the gate; when push comes to shove, money trumps friendship.

The next summer I drove around with Dr. John. It was a very different car, a station wagon used to take his kids to school and bring groceries home to his wife, Libby. He had been married a couple times and had a number of “sprouts.” He also had a ghost he kept with him, a thing that followed him, watched from behind the curtains in the hotel rooms and the plastic-backed chairs in the diners we visited. I mean to say it was his addiction.

By the end of summer, he left his companion with me and I drove alone for the rest of the year.

Then Sal Bernardi picked me up in a car with broken windows and cardboard to keep the cold out. He drove like Mr. Magoo. “Road hog,” cried the New York City cabbies as he careened his “vehicle” down Fifth Avenue toward the Village one snowy December evening in 1978. He was wearing his pajamas and a stocking cap. Sal was always so punk rock. He wrote a melody too tender and too complex to be understood by the alley cats he was inclined to throw his songs at.

The apex of my love life corresponds to my career success, and unfortunately my success corresponded with my drug use. My drug career was short-lived—three years from 1980 to 1983. I quit and headed to France. But the damage was done.

I did drugs like I did everything else. On fire, with no back door. I escaped, of course, and I carried my heart out in a birdcage. But she was burned, and she cried so loud, casting wild notes over water and cloud. Freed of such beauty, she waited to be freed of her sorrow. Maybe that is the picture I see. I turned it into poetry, what else could I do?

By the following spring, Waits and I were back together. I remember driving down La Brea Avenue from the airport. Tom and Chuck liked to pick me up at the airport. There was plenty of traffic so when “Chuck E’s in Love” came on the car radios it echoed across the stoplights and the exhaust pipes. Tectonic plates of culture and music were colliding around us. The three of us, me riding in the middle, were the last Neanderthals, the holdouts of the Tropicana Motel. Once Tom and I moved in together, a way of life ended. Eskimos began migrating south and all the mammoths died away.

My 1957 Lincoln got mangled that summer by Chuck E. and Mark Vaughan who went joyriding while I was on tour. When Tom and I broke up, Tom ditched his Cadillac in self-storage and I left my roughed-up Lincoln with a nurse up north. She worked at the hospital where I nearly died from a heart infection.

I quit driving around with people then. I rented cars and lived in hotels. For a long time I looked over my shoulder thinking there was someone behind me. Just the shade of the demon. I was sober but something was following me.

A collage of images from my Chicago infancy is forever glued to my music. I see rickety wooden fire escapes and recall holding my sister’s hand in an alleyway. I know the smell of dime store lunch counters where Mother and I ate pie in thick coats of cigarette smoke. The carbon monoxide fumes and air brake screech of the city buses we took. Most of all, I remember Riverview Park where terrifying rides and bright lights and loud calliopes enchanted me. Speeding carousels with huge wooden horses I was too small to mount, a perpetual state of fear and longing that became the backdrop for so many songs.

I must have been lost more than once on that fairway, as Mom stood in line for tickets. Outside the bright spotlight I wandered toward the dark sea of an unlit backstage where monsters slept. I was drawn to the darkness and terror. No matter how much a ride frightened me, I begged to go on it again and again.

We left Chicago in 1959 when I was four years old. I grew up in the Arizona of the 1960s. Phoenix was a quiet place in the endless desert, and the radio was our only means of touching the larger world. The Phoenix I knew, ancient and unchanged, is gone now.

My family took such a long trip across America that I felt as if I had always lived in the back seat of our 1959 Pontiac. My big brother Danny and I kicked, poked, and tickled each other in a blender of games that turned the long minutes into long hours. Once I kicked my brother right in the balls and he tore into me like a tornado. I didn’t really know what was down there. He kicked me too. It hurt, but catching the attention of the front-seat referee was not allowed. If Mom said Danny was too rough he might not play with me, so I had to pretend I was not hurt. We were shaping rules not only for hurting each other, but for whom we might be as adults.

On that magical tour into the U.S.A., we saw stalactites in New Mexico, and in Yellowstone National Park we encountered bears rummaging through the garbage like homeless Russian astronauts in fur coats. They were as alien to me as if they had dropped from the sky. I knew them as the cartoon Yogi (“smarter than the average bear”), but in person they were hungry as hell. They came up to our car and demanded food and suddenly I was terrified. “Hurry, roll up the window,” with Mom and Danny laughing. They were always laughing at danger. I couldn’t understand why they didn’t take these things seriously. Finally, our road trip ended in Pomona on my uncle Bob’s doorstep.

America was succumbing to an expanding postwar pressure of social symmetry: be alike, fall in line. In California my family became the idealized version of itself. We had a collie dog just like Lassie and my brother had a raccoon cap like Davy Crockett. We were Walt Disney’s America. Mother wore gloves and Father had a crew cut.

Trying to fit into the Protestant world around them and win the good graces of my Protestant grandmother, my parents baptized me Presbyterian and we attended Presbyterian services. All the rest of my family remained Catholic. It was a terrible source of friction and in spite of everything we tried, the Joneses remained unwelcome in Grandmother’s Temple City. There was an argument and we hit the road, coming to a stop in our new home in the Arizona desert.

The shy desert, a chalky remainder of countless millions of years of other living things. Animals who raised their young on these unforgiving rocks, only to lay down their burden and wait. The skeletons of their lives are the dirt of our cactus gardens. We too will become fossilized pages in some unimaginable future. Well, maybe imaginable: “Look, can you see my fossilized arm—under the Xazzcandra Prelapse? I think it is turning pink again.”

There is a little girl down there we need to talk to. Can you see her? I wonder, do you think she can hear me singing? What’s she doing with that frog?