Читать книгу The State and the Social - Ørnulf Gulbrandsen - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

THE DEVELOPMENT OF TSWANA MERAFE AND THE ARRIVAL OF CHRISTIANITY AND COLONIALISM

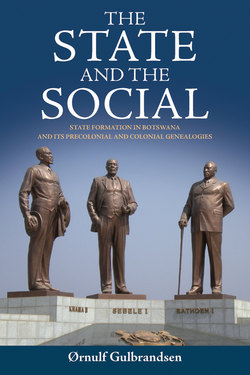

On 3 October 2005 Botswana's state president, Festus Mogae, unveiled what is known as the Three Dikgosi Monument in the capital, Gaborone (see cover of this book). The monument commemorates Kgosi Sechele I of the Bakwena, Kgosi Bathoen I of the Bangwaketse and Kgosi Khama III of the Bangwato, renowned for their diplomatic mission to London in 1895. The president asserted in his speech, ‘During the early years of colonialism these three distinguished monarchs played a leading role in ultimately ensuring our territory's independent future, by preventing its administrative handover to neighbouring white settler regimes’. In such terms the three dikgosi were declared as the founding fathers of the nation, ostensibly preventing the subjection of their countries to Cecil Rhodes's settler regime and the racist regimes of Rhodesia and South Africa. At the time of unveiling, which amounted to no less than a state act of establishing the principal national monument, there were minority voices in Botswana which saw this as an(other) expression of Tswana domination (Parsons 2006: 680).

Neil Parsons (1998: 255) has suggested that the best way to grasp the significance of the dikgosi's journey in 1895 ‘is to ask what would have happened if Khama, Sechele, and Bathoen had not gone to Britain’. Obviously, there were no other leaders in the country at that time representing polities of sufficient strength to engage with the British in efforts to prevent annexation to one of the settler regimes. In the first part of this chapter I shall approach this issue by identifying major historical transformations by which these merafe grew progressively in strength and scale since the late eighteenth century and appeared dominant along the eastern fringe of the Kalahari desert at the time the British decided, hesitantly, to establish the Bechuanaland Protectorate.

This approach will also serve to pursue another major issue of this chapter: the development of the Tswana merafe as a dominant force in relation to a substantial proportion of the population which were included in the Bechuanaland Protectorate and subsequently in the nation-state of Botswana. I shall first explain how, under changing historical conditions, ever-new groups of people were captured into the domain of the Tswana merafe in ways that more and more reinforced their hierarchical order, territorial control and structures of domination radiating from the Tswana royal centres. Thereafter I examine the impacts of evangelizing missionaries, before I address the significance of the British and the establishment of the Bechuanaland Protectorate. I am centrally concerned with how transformations of the major Tswana merafe1 involved a progressive increase of their strength, expansion in scale and rise of Tswana hegemony in the sense I conceived it in the Introduction.

The Development of Tswana Merafe at the Edge of the Kalahari

The Tswana merafe in focus here, as Wilmsen (1989: 101) appropriately states, ‘passed from a peripheral position in the region to almost uncontested dominance’. At first sight this seems surprising as one would not have expected settlements as populous as the royal towns of Northern Tswana merafe to exist in an area with exceptionally poor and erratic rainfall. Moreover, on examining accounts of Tswana societies in the larger region from around 1500 AD, Jean and John Comaroff found that they were characterized by a constant shifting between amalgamation and fission (Comaroff and Comaroff 1991: 127–8), centralization and decentralization (Comaroff and Comaroff 1992: 132). Nevertheless, the Tswana merafe in focus here continued, with few major interruptions,2 to develop in strength and scale from the late eighteenth century, finding their most apparent expression in very large royal towns (Gulbrandsen 2007). In this section I shall give a brief, generalized presentation of processes underpinning the formation of these small states, based, especially, upon extensive historical accounts and analysis I have published previously (Gulbrandsen 1993a, 1993b, 1995, 1996a: Ch. 3, 2007).

Since the London Missionary Society (LMS) had already been active in the region for decades, the British were well informed about the conflicts – often centred round the royal houses – that riddled these polities. On the other hand, the missionaries could also attest to the strengths of their political institutions, particularly the extent to which the Tswana rulers – and their retainers – controlled even the furthest outlying communities in a vast territory. Already in 1824 the LMS missionary Robert Moffat, on visiting the Bangwaketse, was amazed by the size and concentration of the population in well-organized, closely spaced villages: ‘[T]he [royal] town itself appears to cover at least eight times more ground than any town I have yet seen among the Bechuanas [BaTswana]’. He estimated the population to be ‘at the lowest computation, seventy thousands’ (Moffat 1842: 406)3. The kgosi (Makaba, r. 1790–1824) conducted government affairs in ‘a circle…formed with round posts of eight feet high…Behind lay the proper cattle fold, capable of holding many thousand oxen’ (1842: 399). While Makaba was widely reputed to be a dangerous warrior, Moffat conveys an atmosphere of societal harmony. He was not struck by the barracks and military exercises but rather by civic order and the presence of adult men in the kgosi's council (kgotla). Well versed in political life among the Tswana, Moffat – clearly impressed by the manner in which they conducted their meetings in the royal kgotla – speaks of their ‘parliament’, asserting that ‘business is carried on with the most perfect order’ (1842: 346). The idea of the Tswana royal towns as profound manifestations of civic order is also apparent in early missionary accounts of the Southern Tswana merafe (see Comaroff and Comaroff 1991: 129).

These qualities of the Tswana polities were most likely conveyed to the imperial power by LMS missionary Mackenzie who represented ‘a powerful voice…raised in defence of the Tswana’ (Sillery 1965: 39; cf. Dachs 1972: 653f.). Mackenzie worked closely with several dikgosi; his extensive publications reveal an impressive knowledge of Tswana political institutions and practices. For example, he offers an illuminating account of the political proceedings in the royal court of the Bangwato, asserting that they were ‘conducted with decorum and order’ (Mackenzie 1871: 373). In 1882, during the preliminaries to the establishment of the Protectorate (1885), he went to Britain in order to make the case for the Northern Tswana on a tireless campaign for British intervention.4 Sillery relates that Mackenzie's efforts included fostering ‘public enlightenment’ and enlisting ‘many prominent men and an influential section of public opinion’ (Sillery 1965: 39). As evidence of Tswana receptivity to ‘civilization’, Mackenzie could point out that – exceptionally in an African context – several of the dikgosi had been among the first of their people to accept Christianity and undergo baptism, with the consequence that many of their people followed suit (Gulbrandsen 1993a, 1993b; see below in this chapter).

Illustration 1. Robert Moffat, the first LMS missionary to visit the Bangwaketse royal town (1824), preaching to a Tswana local community as rendered on the title page of Moffat's Missionary Labours and Scenes in Southern Africa (1842).

So how could it be that these merafe developed such scale and strength? I shall start examining the process of centralization in these kingdoms with the point of departure in asking how they successfully overcame the conflict-generating ambiguities and contradictions that have often permeated other ‘Southern Bantu’ polities (e.g. see Schapera 1956: 176; cf. Gluckman 1963: 20). Such conflicts relate mainly to succession to office and the exercise of authority once in office. They rose primarily amongst close, rivalling agnates who were able to mobilize sufficient factional support to represent a threatening challenge. However, the conditions for generating such support varied considerably amongst so-called Southern Bantu tribes (see van Warmelo 1974: 56ff, 1930; Schapera 1965: 7f.). Sansom has described how the Tswana (as a major section of the Sotho-speaking peoples) tended to have rulers whose power lay in manipulating bonds and grants concerning people's access to land. He contrasts such ‘Tribal Estate’ regimes (as he calls them) with ‘Chequerboard’ regimes, in which land allocation was decentralized and rulers depended upon ‘reallocating products rather than means of production’ (Sansom 1974: 251). This thesis draws attention to the fact that centralization depended on certain material resources under the ruler's control. But in order to come to terms with the centralizing forces at work during precolonial times among the three major Northern Tswana merafe, we need to examine the rulers' control over cattle rather than land. This notion is by no means an obvious one. Goody, for example, has stated of Africa in general that cattle ‘easily become fused with the personal property of the incumbent; support of livestock is the formula for a very much looser polity. it is difficult to centralise cows’ (Goody 1974: 33). Nevertheless, it is my contention that the centralizing processes of the three Northern Tswana merafe were particularly powerful precisely because of their rulers' exceptional access to cattle (e.g. see Tlou 1985: 69). But note, the conundrum thus presented by the Tswana can be resolved provided we do not seek the answer in the determinist or evolutionist arguments of ecology. Instead, I shall demonstrate that the role played by cattle and cattle-based trade amongst Northern Tswana is mediated through social and political processes that favour not only state formation but a concentrated population as well.

The aggregation of cattle wealth among the ruling families may well reflect the fact that the Tswana – known as an exceptional African case (Radcliffe-Brown 1950: 55) – allow FBD (father's brother's daughter) marriages. Such marriages are practised especially among noble families (Schapera 1957). As the saying goes, ngwana rrangwane, nnyale, kgomo di boele sakeng (child of my father's younger brother, marry me, so the [bride – wealth – bogadi] cattle may return to our kraal). Schapera places particular emphasis on this custom as instrumental in transforming potential rival agnates into supportive matrilaterals, arguing that ‘intermarriage of royals is a means of reinforcing social ties between different (and potentially hostile) branches of the royal line’ (Schapera 1963: 110, cf. 1957: 157). Whether such marriages actually work in practice, however, depends – as the Comaroffs argue – on relationships being ‘skilfully manipulated’ (Comaroff and Comaroff 1981: 44).

The arguments put forward by Schapera and the Comaroffs raise the question of exactly how relationships resulting from royal FBD marriages can be manipulated to amalgamate the power structures surrounding the rulers. The answer varies according to context. In the case of the Northern Tswana, vast cattle herds enabled the rulers not only to exercise such manipulations. They were also highly instrumental in bringing potentially rebellious agnates into dependency as cattle clients.

Cattle clientship is established amongst the Tswana according to their institutions of mafisa and kgamelo. Mafisa is a contractual relationship by which a rich or wealthy herd owner places some of his cattle with another person who herds the cattle for the benefit of milk and some of their offspring. This practice can be found on all levels and at different scales. With the vast royal herds building up as a consequence of the dikgosi's monopolization of the highly beneficial trade of fur and ivory, they had the opportunity to place out large portions of the cattle, not only to potentially challenging rivals, but also a number of important dikgosana. The political significance of this practice as a measure to amalgamate the power structures of the Tswana merafe centred in the bogosi follows from the fact that mafisa cattle could be called back at any time.5 This powerful sanction on political clientship was further reinforced amongst the Bangwato who developed the institution of kgamelo; that is a contract by which the holder was compelled to return not only the cattle initially received by the kgosi, but his entire herd (see Schapera 1984: 249).

Although rise and expansion of the Northern Tswana merafe is attributable to the fact that they were located at the edge of the Kalahari where the dikgosi took great advantage – economically and consequently politically – of their monopolization of the vast wildlife in their respective territories, I reiterate that I do not want to pursue a determinist or evolutionist argument of ecology. The point is that cattle wealth and cattle-based trade amongst the Northern Tswana were mediated through social and political processes that favoured both state formation and large, compact settlements. I thus argue that there is no necessary connection between these processes and the environment (see Gulbrandsen 2007).

This point is particularly evident if we consider the ways in which these merafe expanded during most of the nineteenth century. At this time the Northern Tswana merafe were located in a region characterized by vast unexploited pastures and hunting grounds. Further east, in the present Transvaal, by contrast, demographic and ecological pressure was building up. The consequent violence and warfare brought many groups in flight westwards where they were attracted by a resourceful environment and mostly peacefully harboured in one of the merafe in focus here. These peoples and the peoples who had been conquered and incorporated locally, were of such a magnitude that they in due course comprised the numerical majority (Schapera 1952: v, 1984: 5).

It needs to be explained that unlike other so-called Bantu-speaking peoples in Southern Africa, the Tswana do not form large unilineal exogamous descent groups. On the contrary, the Tswana are organized in sociopolitical units known as kgotla; in English these units have long been referred to as ‘wards’6. Such wards are composed of a number (usually 57) of relatively small, agnatically structured, co-residential descent groups which may be related by marriage (and thus subsequently matrilateral ties). But neither the descent group nor the ward has ever been endogamous. A ward has a distinct location, with a relatively dense settlement pattern, and is also referred to as a motse (‘village’). Each of the agnatic segments is similarly referred to as a kgotla and motse. ‘Kgotla’ is also the name of the descent group's council place located in the open adjacent to the cattle kraal. This open space and the kraal are surrounded by family homesteads, known as malwapa (sing. lolwapa). Each ward is composed of six to eight such elementary entities which, within this context, are ranked with the ward kgosana's kgotla as the most senior one. The wards are the basic sociopolitical building blocks of the merafe, ‘as a basic feature of their social organisation’ (Schapera 1935: 207; cf. Schapera and Roberts 1975). The ward kgosana – who is also the head of the most senior kgotla within the ward – refers either directly to the kgosi or to a senior kgosana who is assigned the responsibility of a number of wards by the kgosi.

The kgotla of the descent group thus constitutes the link between the everyday world of the people and the politico-judicial hierarchy of the morafe. In Chapter 4 I shall elaborate on these interconnections in order to explain their postcolonial significance. Here I shall give an account of the ward as an organizational tool for sociopolitical integration under precolonial and colonial conditions. As already suggested, the wards are composed of a number of agnatic descent groups which are ranked. The ward kgosana is either closely related to the ruler or to a particularly trusted ‘commoner’.

The notion of ‘commoner’ is composite. It includes nonroyals of the ‘original’ stock as well as groups of people conquered or harboured at different historical stages. They are generally ranked according to the length of time they have stayed. Groups incorporated at an early stage were terminologically distinguished from those who could trace their agnatic descent to the founders of the morafe. The latter, named dikgosana, naturally enjoyed superior status. The former were called batlhanka (‘commoners’, lit. servants); which was an honorary matter of holding royal cattle (mafisa, kgamelo) or otherwise assisting the kgosi – indicated by also being titled basimane ba kgosi (the kgosi's boys). Immigrants of more recent origin, called bafaladi (refugees), were in turn ranked lower than the batlhanka.

The dominance of the ruling dynasty is underscored by the fact that those identified as bafaladi might, in the larger Tswana world, be of higher rank than even the hosting kgosi. For example, today there are groups categorized as bafaladi who can trace their origin to the ruling dynasty of the Hurutshe, who are recognized as senior to all three of the merafe under consideration here. Such ‘downgrading’ in the hierarchical order is, as indicated in the Introduction, justified by the Tswana maxim of ra tlou e tlola noka ke tloutstwane (‘when an elephant crosses a river, it becomes a small elephant’).

Finally, there was a distinct ‘underclass’ of people (mainly San and Bakgalagadi). As the dominant Tswana groups expanded their herds – and therefore needed larger territories and more herd labour – they stripped such people of any livestock they might have and put them to work for wealthy families, either as herders or as domestic servants. People belonging to this often-despised category, called malata, thus became part of the morafe on terms that amounted to serfdom (Wilmsen 1989: 99). For example, they were ‘deprived of their children or transferred from one man to another’ (Schapera 1984: 32; cf. Tlou 1977; Wilmsen 1989: 285ff.), a practice prevailing at least until midcolonial times. In such circumstances, it is comprehensible that there evolved a Tswana notion of a huge contrast between the ruling group found at the kgotla kgosing (‘kgosi's court’ or ‘the royal kgotla’) in the royal town – the epitome of ‘civilization' – and the mobile, ‘lawless’ people of the bush – hence ‘bushmen’. This hierarchical order is underpinned by an elaborate code of rank and respect, reproduced in a multitude of contexts – precolonial as well as postcolonial – spanning from the elementary family group to the royal court.

Socio-politically, this means that foreigners were systematically – and tightly – incorporated into the hierarchical sociopolitical order of wards which was spatially concentrated in large royal towns or compact outlying villages (this did of course not pertain to the mentioned ‘underclass’ of serfs unless they were brought in as domestic servants). This was, however, not only a matter of placement in the sociopolitical hierarchical structure. The forceful apparatus of capture at work in these merafe involved a persistent mill of cultural assimilation through the everyday practices of litigation in the context of the hierarchy of courts spanning from the kgotla of single descent group to the royal kgotla (see Chapter 4). It was by virtue of these processes that vast numbers of conquered or hosted groups, in due course, assumed primary identification with the Tswana morafe in which they were incorporated.

The significance of this apparatus of capture – in the sense of Deleuze and Guattari (1991: 360) – is particularly apparent at times when larger communities were to be integrated, in which case they might be divided and distributed among various wards. In this way they were strictly subject to the hierarchy of the morafe, located spatially close to the political centre and always under close surveillance by the ruler's retainers. This practice gave rise to systematized power relations radically different from those of other Southern Bantu polities, where large descent groups were allowed to develop in ways that more frequently led to factionalism and succession (see Schapera 1956: 175).

In this context it is particularly important that among the Northern Tswana the division of descent groups into small sections distributed between different wards gave rise to networks of crosscutting loyalties, facilitating the ruler's exercise of checks and balances of power. The consequent strengthening of the central power was evident from the fact that the authority of ward kgosana and their deputies was largely a matter of delegation and thus subject to the ruler's control. In addition, the kgosi had the authority to reshuffle the distribution of agnatic segments among the various wards or – as occasionally also happened – pick such segments from different wards in the pursuit of constructing a new ward.

Nevertheless, the fact that immigrants were brought under the immediate authority of a ward kgosana does not mean that their incorporation automatically contributed to the strength of the ruler. That of course depended on the ruler's control of the respective dikgosana. Significantly, a substantial number of these dikgosana were members of the royal family, some of them close enough to the ruling line to represent a challenge to the ruler. This means that if the rulers lacked the measures to ensure the dikgosana's support, immigration might well have aggravated rivalry for the bogosi.

It is in this context that the significance of cattle manifests itself as a measure to amalgamate the power structures surrounding the kgosi and counteract such challenges: being in control of vast herds, the kgosi was not only in a position to bring potentially challenging agnates into a position of dependency. By the formation of a network of cattle clientship amongst commoner dikgosana, the kgosi both gathered political support against rebellious agnates and loyalty amongst those who were delegated the authority to integrate the vast numbers of ‘foreigners’ into the hierarchical sociopolitical order of the morafe. From this position of strength, the three merafe in focus here expanded their respective territories and brought under their domination a number of outlying communities (Gulbrandsen 1993b). These subject communities were instrumental both in exploiting the hunting territories to the benefit of the kgosi, to whom they also were compelled to pay levies and tax, and to herd the large royal herds and those of wealthy, high-ranking people.

This trend of trade and accumulation of cattle centred in the bogosi should, however, not be taken as an indication that the rulers of these merafe operated in a region that was characterized by peace and harmony. During the first part of the nineteenth century the various Tswana groups of this region frequently raided each other and occasionally engaged in conflicts that amounted to small warfare (Schapera 1942a: 13–14, 1952: 21; Parsons 1982: 118). Such violence found, of course, its major culmination during the devastating intrusion of the Matabele, known as difaqane, by which the Tswana were conquered and dispersed for more than a decade (c.1825–1837). Yet in the long run, these aggressive actions served, on the whole, to consolidate and strengthen the three merafe under discussion. As so often happens in times of serious conflict, the central power, being in control of the age regiments, provided the necessary internal cohesion and thus became vitally important (see Cohen 1985: 276). In particular the kgosi, as commander-in-chief and recipient of booty (both cattle and people), gained considerable authority.

All these merafe were at times stricken by serious dynastic conflicts, occasionally to the extent that a morafe was temporarily separated into mutually independent sections, yet in due course reunited by one conquering the other (see Schapera 1952: 12). In the manner known from indigenous polities all over the subcontinent (Gluckman 1963: 9ff), conflicts within ruling families might lead to secession of a splinter group. In the present context, after the Bangwaketse and Bangwato departed from the Bakwena in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century,7 Batawana's secession from the Bangwato is the only case which resulted in a permanently independent morafe. There are several reasons for this (see Schapera 1952: 15ff), including reconciliation and return, hosting by another morafe and, most importantly, the British policy that all inhabitants of the territory – the ‘native reserve’ in British terms – were compelled to submit to the authority of the Tswana kgosi recognized by the colonial power and granted extensive credentials (see below). At any rate, on the basis of Schapera's (1952: 11–15) meticulous accounts it is evident that very few, if any, royal sections of the merafe here have prevailed permanently beyond their royal centres and represented a potentially challenging force.

In summary, I have argued that the strength and scale of the Northern Tswana merafe in focus here were in progress from the late eighteenth century, mainly conditioned by the linking up with long-distance trade, abundance of wildlife, vast unexploited pastures and incessant population increase by capturing numerous alien groups into their structures. That is, people were either searching for safe harbour in an increasingly violent landscape or conquered and subjected to one of the merafe. Under these conditions, I have argued, the three Tswana merafe in focus here underwent major transformations, the two significant ones relevant to the present argument being: (a) the amalgamation of the power structures around the dikgosi by the formation of cattle clientship of nonroyal leaders, including some of those of foreign origin; (b) the use of the ward system, combined with cattle clientship, which enabled the ruling groups to incorporate people conquered and hosted in ways that effectively put them into the mill of assimilation and made them integral to the hierarchal structure of the merafe, adding progressively to their strength and scale.

The decisive mediating factor was cattle herds which grow fast under favourable ecological conditions and the dikgosi's exclusive linking up with the intercontinental trade of fur and ivory and their control of trading in the region. The propelling factors were thus of a global kind – intercontinental trade and the imperial expansion into the continent that brought numerous communities and families in flight westwards from the most troubled areas. (By the way, it is a highly intriguing point that, as I shall explain in Chapter 3, cattle – in combination with global trade connections – played a similarly crucial significance in the formation of the postcolonial state in Botswana.)

As for people, I have explained that the rise of the Tswana merafe went hand in hand with that core group in due course becoming a numerical minority. In control of bogosi, they prevailed as the ruling communities progressively asserted their dominant position. By means of particular practices of social incorporation and cultural assimilation, political integration of groups conquered or hosted in the royal centres worked to the effect of developing primary identification with the core group which recognized them as full members of their morafe (see Chapter 6). This is, however, not the whole story. Within the vast territories claimed by the merafe, there were always a number of outlying communities that resisted the overlordship of the rulers of the Tswana merafe of present concern. They were mostly of foreign origin, but also included groups seceded from the royal centre of other Tswana communities in the region. In order to comprehend how the Tswana merafe consolidated and expanded their domination at the edge of the Kalahari and beyond, I shall, in a subsequent section, explain the significance of being brought under British overlordship.

Anticipating that, let me point out that the transformations I have been concerned with in this section involved the development of a civic government (puso) highly instrumental to the British establishment of a colonial state in the country, confirmed by Roberts' (1972: 103) assertion that ‘the administrators of the Bechuanaland Protectorate had at their disposal from the outset a group of closely similar and already highly sophisticated judicial systems, the higher levels of which could be incorporated in the official structure almost without modification’. One of the most apparent expressions of civic order was the centrality of the kgotla in the structuring of social life and the settlement pattern, conspicuously manifested in the compact, well-organized royal towns of thousands of people with the royal house at the core (see Gulbrandsen 2007, cf. 1993b). The evangelizing missionaries had already impacted upon these orders for decades before the establishment of the colonial state in 1885. To their engagement with the dikgosi – and the dikgosi with them – we now turn in order to come to terms with their significance.

Strengthening Royal Ancestorhood, Receiving Evangelizing Missionaries and Establishing State Churches

Although the Bakwena, the Bangwaketse and the Bangwato were, at times, riddled by internal conflicts, they succeeded in taking control of many smaller and larger communities, either conquered or hosted. Their respective dynasties had occasionally proved their ability both to stand up to external threats and to force, if necessary, foreign groups into submission. In Tswana thought, royal authority is not only a matter of ascription by virtue of descent: it has to be asserted by a demonstration of strength and the fruits of good governance in the form of welfare, health and prosperity of the population – all proofs being supported by the royal ancestorhood (see Gulbrandsen 1995).

The authority of the ruling dynasty is cosmologically linked to a hierarchy of forces. In the Tswana imagination, this hierarchy is, in brief, projected into the realm of the ancestors (badimo). In this mode of thought, the ancestors of the ruling line (badimo ya dikgosi) constitute the supreme source of power, wisdom and morality, exclusively available to the living ruler. Furthermore, a kgosi is ideally in possession of the most powerful charms to protect himself and the bogosi against internal enemies and guard the morafe against threatening external forces. In addition the kgosi should ideally be in control of the most powerful productive medicines, e.g. for providing rain (see Chapter 8 below; Gulbrandsen 1995). A kgosi who acts in relation to external forces with strength and sustains internal control is spoken of as a kgosi who relates well to his ancestors and asserts his command of productive and protective ‘medicines’.

The notion of a Tswana ruler's authority was dependent not only on descent but also on his personal strength and ability to act upon ever changing historical contexts to the benefit of his people. This is a notion – capacity and engagement – which is intrinsic to the cultural construction of the kgosi as a ruler with, as we shall see, considerable authority to initiate major transformations. This dimension of pragmatic assessment of a ruler's strength and ability is perfectly expressed by the mythological origin of the ruling lines of the Bakwena and Bangwaketse. As for the latter, I was told more than once, in the words of one man, that:

Long ago, there were two brothers, Kuto and Kutoyane, who were the sons of Moleta, one of the ancient dikgosi of the Bangwaketse. Kuto was the eldest one [as indicated by the diminutive form Kutoyane given to the younger brother]. However, although Kuto was the one who according to our custom [mokgwa] should succeed his father, this did not happen. The reason is that Kuto, in the opinion of the people at that time, was found to be too weak. They wanted Kutoyane, who they thought would be a much more forceful kgosi. I think they were very right, because ever since the Bangwaketse have been ruled by people descending from Kutoyane and they have proved to be very strong and wise, like Makaba II, Gaseitisiwe, Bathoen I, Seepapitso III and Bathoen II. The people of Kuto still live here in Kanye and much respect is paid to them, especially their seniors – although they do not have sufficient force to rule people. Their head has a very senior position in the royal kgotla, placed at the right-hand side of the kgosi among his paternal uncles and principal advisors. At the time the Bangwaketse adhered properly to the ritual practice of go loma ngwaka [‘to bite the new year’ – the first fruit ceremony], the head of the Kuto people was the one to bite the pumpkin first, even before the kgosi.

The LMS missionary Willoughby relates a similar myth about a ‘junior’ line constituting the ruling dynasty among the Bakwena (Willoughby 1928: 229). The central notion here, of strength being attributed to a genealogical line of rulers, comes out of the Tswana cultural construction of kgosi authority. Ideally, the kgosi is a motswadintle (‘one from whom good things come’; see Gulbrandsen 1995: 421), ensuring societal order and thus social harmony (kagiso). As I shall elaborate in Chapter 4, kagiso is imperative to health, fertility, prosperity and welfare. In popular imagination, a powerful kgosi is a kgosi who provides kagiso for the morafe at large because he is perceived as being on good terms with the principal custodians of the morafe's moral order, the royal ancestorhood (badimo ya kgosi). A kgosi's authority – as the incumbent of the bogosi – thus springs to a significant extent from his exclusive access to the royal ancestorhood. Yet, I reiterate, it also depends on his actual ability to act with strength and determination to the benefit of the morafe as proof of ancestral support. In terms of Tswana cosmology, if he does well, he will, at his death and subsequent inclusion in the royal ancestorhood, add to the popular perceived strength of the ruling dynasty (see Gulbrandsen 1993b: 566ff.).

The preceding section illuminates how Tswana dikgosi attempted to amalgamate the expanding networks of power that enabled them to prevail as forceful rulers of a morafe that expanded in strength and scale. For example, the Bangwaketse extraordinarily powerful hero-king Makaba II features, even today, prominently in popular consciousness about the force vested in the ruling dynasty's ancestorhood. His great significance is currently most apparent in the symbolism in the royal kgotla of the hierarchical order of bogosi: the senior living descendants of the senior male line descending from each of his wives are, in ranked order according to the ranking of the wives, situated on the right-hand side of the kgosi in the royal kgotla, with the most senior descendant next to the kgosi.

Tswana dikgosi are not to be classified as ‘sacred kings’ (e.g. of the kind analyzed by de Heusch (1982) in Central African contexts). But their responsibility for their people's overall health, prosperity and welfare instilled them with major tasks that could not easily be taken care of solely through the stratagems of amalgamating and expanding networks of power. Their spiritual leadership is required for providing rain and preventing the influx of pests and plagues, depending on a range of ritual practices. That is, practices which are, on the one hand, directed towards satisfaction of the royal ancestorhood (see Chapter 4) and, on the other hand, involving deployment of powerful ‘medicine’, ideally provided by the strongest doctors/diviners (dingaka, singl. ngaka) available. They are often of foreign origin, reflecting a belief in their capacity to convey constructively highly potent, potentially dangerous spiritual forces prevailing beyond the limits of the morafe.

It is in the light of this obsession with empowerment and fortification by spiritual means as well as more tangible forces that we should understand why a number of Tswana dikgosi were, unlike many other African rulers, amongst the first to be baptized, engaging extensively with evangelizing missionaries who were often attracted to establish a church in the royal town and subsequently in outlying villages.8 David Livingstone of the London Missionary Society was the first to be stationed in what would become the Bechuanaland Protectorate. The Bakwena (see Map 1), amongst whom he worked and lived for about ten years from 1842, were at that time under repeated attack by the Boers, and missionaries were ostensibly helpful both with strategic information and arms (Sillery 1954: 110).

On the other hand, missionary requirements that the dikgosi impose radical changes in several important ritual and social practices9 gave raise to major conflicts at the royal centres (see Gulbrandsen 1993a: 50 ff). For example the missionaries obliged the dikgosi to abandon all but one of their wives, famously illuminated by the aftermath of Livingston's baptism of Kgosi Sechele I of Bakwena (r. 1831–92, see front cover of this book) in 1848 involving major conflicts with some of his senior dikgosana (see Livingstone 1857: 13ff.; Schapera 1960: 298ff.). Amongst the Bangwato, tension and conflicts emerged in 1860 when Kgosi Sekhoma – who was highly ambivalent, if not hostile, to the evangelizing missionaries – and his son and heir Khama became bitterly divided as the latter refused to participate in the initiation ceremony (bogwera) after having been baptized. There were violent confrontations around the royal town of Shoshong between Sekhoma's and Khama's supporters (see Illustration 2), before a process of reconciliation (tetlanyo) started and ultimately led to the enthronement of Kgosi Khama III (r. 1872, 1875–1923, see front cover of this book).10 However serious, these conflicts were in due course resolved; after the Khama had taken full control of the bogosi, he was never seriously challenged by anti-Christian or anti-missionary factions.

Illustration 2. ‘Battles outside Shoshong’ as rendered by LMS missionary John Mackenzie (1883: 246)

While it is true that the missionary-kgosi relationship could, at times, become tense and even conflict ridden, in some important respects the kgosi was the stronger party because the evangelizing missionaries depended on his permission to establish a church in his morafe. Usually, the dikgosi allowed only one missionary church to be established (Schapera 1970: 122), which they attempted to capture into their polity. That the dikgosi and their close retainers functioned as the church elderhood epitomizes the extent of their engagement. As I have argued elsewhere (Gulbrandsen 1993a: 49ff.), this meant that the missionary churches tended to take on the character of a ‘state church’. Landau (1995: 51) emphasizes the missionaries' dependency on the dikgosi, one of whom pointed out that ‘[i]n a very true sense Khama is head of the Church as well as head of the State’. Likewise, during a celebration in the royal kgotla, a prominent man asserted that Kgosi Khama ‘reigns through the Church. His reign is established by God’ (Landau 1995: 52). Echoing European notions of church-monarchy relations, Khama himself declared that ‘[t]he Lord Jesus Christ…made me a chief, and He knows how I try and have always tried to rule my people for their good’.11

By these constructions, several dikgosi hence attempted – to a great extent successfully – to add a new spiritual dimension to their respective bogosi. For example, when Kgosi Bathoen II of the Bangwaketse (r. 1928–1969) played the organ during church service, he was both asserting his divine connection and naturalizing Western idioms of eminence into Tswana hierarchical thought. This did not conflict with the kgosi's centrality in indigenous cosmology which was continuously reproduced in the discursive field of the kgotla – the locus of ancestral morality – into which also the missionaries were drawn, e.g. in the conduct of Christianized ritual practices, like praying for rain (see Gulbrandsen 1993a: 68–70).

The consequent close relationship between dikgosi and the evangelizing missionaries was the prevailing pattern amongst the Northern Tswana – to the extent that the missionary church assumed the character of being a ‘state church’. To a very limited extent ‘the spiritual aspect of the chieftainship’ drew a wedge between ‘religion and politics, chapel and chieftainship’ as Comaroff and Comaroff (1986: 4–5) report in the case of the Southern Tswana. But there were a few exceptions, as for example in the case of Kgosi Kgama who ran into a serious conflict with the missionary resident in the royal town that instigated the formation of a challenging faction (in 1894), entailing a major controversy which also involved the protectorate administration (Chirenje 1978: 35ff.). However, Khama prevailed as a Christian kgosi. Amongst the Bakwena a controversy over the initiation ceremony of bogwera also entailed factionalism and a major conflict at the royal centre that implicated the missionaries; I shall discuss this case in the following chapter.

In the case of the Bangwaketse, an indigenous LMS priest, Mothowagae, came acutely at odds with the resident missionary and he established an independent church – King Edward BaNgwaketse Church. This gave rise to a major divide amongst the Bangwaketse, manifesting itself in a serious conflict between Kgosi Bathoen I (r. 1889–1910, see front cover of this volume) who was attached to the missionary, and important dikgosana who supported Mothowagae. Their support was largely influenced by an emerging rivalry between Bathoen and his younger brother, Kwenaetsile. As I explain extensively elsewhere (Gulbrandsen 2001: 44ff.), the dikgosana were unhappy with the kgosi's close association with the resident missionary and his consequent reform and abandonment of important ritual and social practices. Mothowagae exploited this rift by expressing adherence to Tswana cultural practices. This he allegedly articulated in a charismatic manner that prompted the missionary to accuse Mothowagae of having brought ‘Ethopianism’ to the Bangwaketse. At the same time the dikgosana exploited this development to build up a second political centre. Kgosi Bathoen prevailed, however, because Kwenaeitsile died. But there was also a perceived threat emerging toward bogosi represented by independent church movements to which the dikgosana felt equally vulnerable as the kgosi.

Apart from capturing Christianity in the effort to adding another spiritual dimension to the bogosi, it became increasingly evident that the kgosi's control over the missionary church was highly conducive – from the point of view of the royal centre – to sustaining spiritual control within the morafe. During the latter part of the nineteenth century an increasing number of young men migrating to industrial and mineral centres of South Africa were exposed to indigenous church movements, lead by people who had departed from a missionary church. Some of these church movements also attempted to expand into the Tswana merafe, where they were fiercely rejected as potentially disruptive to social order and a major challenge to kgosi authority (see Gulbrandsen 2001: 49ff. for an extensive account).

Thus, by granting a missionary society a monopoly on evangelization and taking firm control over the church and its congregation, the dikgosi virtually gave rise to state churches. Quite pragmatically, virtually all the Tswana dikgosi recognized by the British (see below) privileged the missionary churches with a monopoly since they represented a powerful instrument preventing syncretistic movements – as dangerous exterior forces – from generating rhizomic attacks. Especially the provincial communities represented potentialities of such forces (Gulbrandsen forthc.), the supervision of which was tacitly conducted by the network of clergies extending from the royal centre. In particular, to keep at bay forces giving rise to challenging independent church movements was at least as much in the interest of the missionary church as the ruling groups of the Tswana merafe. Before the dikgosi lost their control over the establishment of churches at Botswana's independence, there seems to have been only one instance (in the 1930s) when one such movement temporarily became of some significance in a dynastic conflict at the Bakgatla royal centre (Morton 1987: 88f.; Gulbrandsen 1991: 52f.).

Negotiating Protection: Threats of Annexation and the Establishment of a Colonial State

The formation of the Bechuanaland Protectorate cannot, however, be characterized as entirely a matter of ‘love at first encounter’. Negotiations with each kgosi were conducted by a colonial officer – Charles Warren – who was met by the Bakwena with some reluctance, but shown considerable appreciation by the Bangwato (see Ramsay 1998: 66ff, on whose excellent account much of the following relies). Scepticism was only to be expected in view of British expansion into the region over the past decades. Indeed, this expansion was at one point perceived as such a serious threat that initiatives were made to unite various Tswana merafe, including the Bakwena and the Bangwaketse, into a confederation to resist what they considered British aggression. Such a confederation never materialized, however. The Northern Tswana rulers Gaseitsiwe (Bangwaketse) and Sechele (Bakwena) remained spectators to the violence perpetrated by the British in order to safeguard the diamond fields in and around Kimberley.

When they eventually welcomed the British offer of ‘protection’, their acquiescence should be understood against a background of other colonizing forces at work which was perceived by Northern Tswana as an indeed dangerous threat. These were settler communities – British as well as Boers – which were by no means under British control and which pushed for expansion into the territories of the Northern Tswana merafe. This led to some violent interactions in the early 1880s (Ramsay 1998: 65).

In the context of such dangers, and given that they had no chance of resisting the British if the latter really had wanted to gain the Northern Tswana land, the three dikgosi consented to the establishment of the Bechuanaland Protectorate. The deal was after all quite acceptable, since the British had promised that ‘the chiefs…might be left to govern their own tribes in their own fashion’12 and, very significantly, the colonial power firmly restricted the establishment of white settler communities within the tribal territories. The Northern Tswana's geopolitical location had worked to their advantage: the decision to establish a British protectorate was triggered by increasing German activity in what was then South-West Africa. Was there now, the British asked themselves, a ‘danger that the Germans might join hands with the hostile Boers, or with the Portuguese, or even with other Germans who were in East Africa, cut the road to the north and thus permanently bar the Cape from access to central Africa?’ (Sillery 1974: 75). As Maylam (1980: 25) states, being ‘in danger from three sides: South African Republic, Germany and Portugal’ the establishment of the Bechuanaland Protectorate served the British imperial interests in blocking South African and German expansion. These interests were more than ‘political’ (Parsons 1985: 29) as the control over the vast territory of the protectorate helped significantly to secure economic interests further north, especially by the construction of a railway through the country which remained the only direct link between South Africa and Rhodesia until the 1960s.

That the British considered negotiating the establishment of a protectorate was also due to the existence of somebody to address. That is, somebody in sufficient control of the country and people to be recognized as a partner with enough local authority and political control. Hence the significance of the strength and scale of the Bakwena, the Bangwaketse and Bangwato merafe to be brought under the British wing in order to avoid annexation to the neighbouring violent states.

The negotiated agreement proved, however, not to be watertight. After only a few years the British saw the protectorate as a base for imperial expansion into central Africa. Meanwhile Cecil Rhodes emerged as a leading figure capable of imposing colonial rule on the protectorate. Queen Victoria paved the way for his British South Africa Company (BSACo) to take control, which encouraged the British to push for more than mere ‘protection’. In an Order-in-Council the British denied the sovereignty of the dikgosi and gave themselves absolute power over all the territories of the Bechuanaland Protectorate. This set in motion a power struggle between the dikgosi and the colonial agencies during which the former's strength was severely tested. On at least one occasion, the British and the Tswana were on the brink of war. Aware that the dikgosi might join forces, the high commissioner decided to give in, and this particular confrontation was resolved peacefully. The British, however, had not abandoned their plans to transfer the protectorate to the BSACo. Rhodes at this time was at the height of his power: ‘For him direct control of Bechuanaland was the stepping stone to the realisation of his greater ambition – to seize the gold-rich Transvaal’ (Ramsay 1998: 75).

Alarmed by the possibility of annexation, the dikgosi of the Bakwena, Bangwaketse and Bangwato embarked on the famous journey to London (September-November 1895) mentioned above. Not only did they take their case to the British government, they mounted a lengthy – and successful – campaign throughout Britain against the BSACo, accompanied by missionaries and presenting themselves as model Christian rulers. Asking what would have happened if Bathoen, Khama and Sechele had not travelled to Britain, Parsons suggests, I recall, that the protectorate would have been taken over in October-November 1895. Instead, the dikgosi's effect on the electorate made Prime Minister Chamberlain ‘obliged to make partial concessions to the chiefs’ and held him back from ‘throwing his lot completely into the Rhodesian camp’ (Parsons 1998: 255). Perhaps most significantly, their lobbying in London had such an impact on the Colonial Office that it complicated a plan by Rhodes to attack the Boer government. Since this venture subsequently failed to the extent that it became an international scandal, Rhodes's political standing was significantly reduced. The British government abandoned its plans to leave his company with most of the Bechuanaland Protectorate and renewed its promise to protect Bechuanaland. Having apparently defeated Rhodes, the dikgosi were celebrated as heroes by their followers.

And yet, the ostensible promise of ‘protection’ represented no definite guarantee against annexation. In the wake of the South African war, the British government ‘began to press for the transfer of the Protectorate to the control of the nascent Union of South Africa’ (Ramsay 1998: 82). Once again the dikgosi headed campaigns against such plans, and in 1909 they made a second journey to London, where ‘the Batswana leaders’ views had an immediate, if immeasurable, effect on public discussions'. The Times remarked on their ‘skill in elocution’, concluding that ‘[t]he speeches of these barbarian chiefs…are far better reading than the speeches of most European statesmen’.13

Although the success of the Tswana dikgosi certainly owes considerably to their personal capacity, it must be stressed that their endeavours were decisively conditioned by the conjunction of particular historical circumstance. First, the strength of their respective polities, centred round large, well-organized royal towns and their extent of control over many outlying communities perfectly matched the British strong desire of running the protectorate at minimal cost by implementing extensively practices of indirect rule from the outset by leaving ‘the traditional organization very much alone’ (Ashton 1947). Second, the dikgosi's development of a close, supportive attachment to the London Missionary Society facilitated the development of the British-Tswana relationship. Third, the new orientations emerging amongst ruling groups of the Bakwena, Bangwato and Bangwaketse underpinning the dikgosi's efforts to ensure British protection, was conditioned by the threat of being captured into the violent domains of the expanding settler regimes immediately east and north of their own territories.

Finally, despite their capacity of incorporating and assimilating foreign groups, these processes were, however, not complete: during the latter part of the eighteenth century a number of communities, some of which large and strong, were located within the territory claimed by one of the three Tswana merafe. As we shall now see, with a privileged position within the colonial state, the dominant position of their ruling communities in relation to other communities was progressively reinforced.

Expansion of the Dominant Tswana Merafe under the British Wing

After the Bechuanaland Protectorate had been established in 1885, the eight Tswana merafe officially recognized by the British were each designated a distinct, demarcated territory, known as ‘native reserve’ (see Schapera 1943a: 7ff.; Motzafi-Haller 2002: 86ff.).14 A kgosi was established as the ‘native’ authority in charge of all the peoples living in each of them. Furthermore, during the three dikgosi's visit to England in 1895, the British made it clear that they would be given full backing, if required, to prevent junior sections of the ruling dynasty from branching off and forming separate establishments. The rulers of these merafe were hence installed by the British as the supreme authority of all those communities living within their respective reserves. This also meant, as suggested previously, that groups that had seceded from the royal centre and taken residence elsewhere, were now subjected to the overlordship of the Tswana kgosi recognized by the British (Schapera 1952: 17). The dikgosi were assured full support in case subject communities should challenge their overlordship. In this section I shall explain how the dominant Tswana expanded the network of power with their respective reserves and how the increasingly repressive structures were countered by resistance.

As suggested in the Introduction, there were huge differences among the eight ‘native reserves’, both in territorial range (see Map 1) and population size (see Schapera 1952). Moreover, they differed sharply in the extent to which foreign groups were assimilated into a recognized morafe.15 The three smallest ones – the Barolong, the Malete and the Batlokwa – occupied minute areas and were quite homogenous, with no unassimilated groups of any significance except for a small category of servants (batlankha). The Bakgatla were also relatively homogenous, small in number and confined to a relatively small territory, yet, as we shall see, with one distinct Tswana community with non-Kgatla identification. Of the four larger territories – the Bangwaketse, the Bakwena, the Bangwato and the Batawana – the first two included some sizeable communities which identified themselves as Tswana, but originated from sections different from the three ‘hosting’ merafe. In addition, a considerable number of people were scattered around in small villages or hamlets: as discussed earlier in this chapter, these consisted partly of small groups originating from Sotho-speaking communities in the Transvaal, and partly of people who had ‘always’ been living in the area and who were classified by the ruling Tswana groups as Makgalagadi or Masarwa.16 When the dominant Tswana communities increased their cattle wealth from the eighteenth century onwards, the latter categories constituted a source of free labour and consequently were exploited as herders. This was particularly the case among the four large merafe. The Bangwato and the Batawana were granted the most extensive ‘native reserves’; they also were assigned overlordship of great numbers of people who had retained their non-Tswana cultural identities.

By the exercise of their dominant position, all communities within the confines of each native reserve were captured into the hierarchical structure of authority radiating from the royal centre of the officially recognized merafe. The Tswana ruling group exercised their power by means of this network: formally on behalf of the Crown, they administered the allocation of natural resources, collected tax and exercised jurisdiction. The heads of provincial communities were recruited either from the local group or from members of the royal centre who were placed in provincial communities to embody the authority of the kgosi officially recognized by the colonial state. During the colonial era such delegation by the dikgosi increased, with a system of ‘chief's representatives’ originating from the royal centre and also an extensive intelligence service.

This system worked more efficiently in compact communities, especially those closer to the royal centres, than in peripheral communities in large ‘reserves’ such as those of the Bangwato and Batawana. On the other hand these peripheral communities, composed mainly of hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists, were politically inactive and thus represented no threat to the Tswana rulers. Moreover, although the majority of the population in the reserves lived in compact villages, being agriculturalists and pastoralists they operated over a wide area: a family's arable land could be located 500 kilometres from their village and their cattle post even further away. As all land resources were ‘communal’, and under the trusteeship of the kgosi access to land could be obtained only with the consent of the kgosi or one of his deputies, by appointing ‘overseers’ to administer all the areas used for agricultural and pastoral purposes (see Schapera 1943a: 143, 224ff), the dikgosi kept control of this particular part of the hierarchical network.

It needs to be stressed, however, that communities foreign to the Tswana merafe were brought under their domination to a highly different extent. This had partly to do with space. For example, while one Kalanga group was so closely connected to the royal centre of the Bangwato that it constituted a separate ward in the royal town, other Kalanga groups were living far away at the fringes of the territory which the Bangwato attempted to control, allowing them considerable de facto autonomy (Werbner 2004: 37; cf. van Binsbergen 1994: 156; Schapera 1952: 65ff). Partly this was a matter of power: while most ‘foreign’ Tswana-speaking communities were tightly integrated with the royal centre, there were some large Tswana communities which, as we shall see subsequently, were not located far from the royal centre yet always challenged the supremacy of the ruler of the ‘hosting’ morafe.

In any case, the domination of the Tswana merafe recognized by the British prevailed. The force of the processes and structures of subjection is testified by the fact that during the colonial era – spanning some eighty years – there were very few rebellions or serious conflicts between the dominant Tswana groups and their subject communities. It also reflects the fact that the leaders of these subject communities often perceived some benefit in submitting to the dominant morafe. For example, in 1922 a large contingent of Herero (originating from the present Namibia) sought refuge among the Bangwato and were accommodated by the establishment of a separate ward in 1922 (see Durham 1993: 72, 130–31). Furthermore, among the sizeable, composite population designated by the Tswana as Makgalagadi, who were mostly scattered among small hamlets, there were groups which gathered under the leadership of a kgosana and formed Tswana-style settlements, centring on compact villages divided into lekgotla.

I lived for a year in such a village in southeastern Bangwaketse that had been established at a small lake in the southern part of the ‘reserve’ and brought into the political order of the Bangwaketse at the time of Kgosi Seepapitso III (c. 1915). In 1946 his son, Kgosi Bathoen II, moved the people of this community some 15 kilometres towards the north and placed it under the authority of one of his dikgosana who were located there in a separate ward with five descent groups from different wards in the royal town. They were, without question, compelled by the kgosi to move in order to give the kgosi's representative a substantial support group. The group of people brought from the south were identified by the Bangwaketse of the royal town as X; their actual name I do not relate for reasons that will be obvious shortly. This group met this reorganization with considerable ambivalence, if not resistance.17 On the one hand, it linked them more closely to the hierarchical order of the Bangwaketse, thus clearly ranking them above those who were, as one of their elders put it, still living in the bush. Moreover, the position of their leader (to whom I was able to speak shortly before he died in 1977) was strengthened within his own community, and he asserted that he worked well with Kgosi Bathoen's kgosana. On the other hand, the Bangwaketse group from the royal centre – constituting the senior ward in the village – never accepted X as Bangwaketse ‘proper’.18 When I came to the community thirty years after it was established, there had been – with one exception – no intermarriage between the X and those who claimed to be bona fide Bangwaketse. Yet the X insisted to me that they were Bangwaketse ‘just like everybody else in the village’, and they made every effort to appear indistinguishable from them. The story of the X offers a perfect illustration of how the dominant Tswana group had inculcated their holistic ontology of an all-embracing hierarchical order – there was nothing else to aspire for than belonging to the dominant Tswana.

Similarly I have come across other groups of ‘Bakgalagadi’ Tswana in a number of small provincial communities in Eastern Botswana who were hiding their perceived stigmatized identity and asserting their belonging to the dominant Tswana (see Solway 1994; Chapter 5 below). This aspect came out in an intriguing way at Botswana's independence when the ruling group of the postcolonial state embarked on constructing a ‘nation’ principled upon nondiscrimination and other virtues of equality (see following chapter). It became a matter of offence that could be prosecuted to address minorities by the degrading prefix of ‘Ma’, as in Makgalagadi and Masarwa, the stigmatising Setswana label of Makalaka for Kalanga, or even by the use of their distinct group name if they themselves perceived it humiliating, as in the case of the X above. This and many other communities insisted on being identified by the name of the morafe that claimed ownership to the territory in which they were living.19 I was told by people who identified themselves as Bangwaketse proper in the village in which I was living that if ‘if you call them X, they might hit you or take you to court!’ Tswana hegemony had obviously been forcefully at work. I shall pursue the issues of domination and pressure for assimilation in Chapter 5.

While many groups thus submitted rather quietly to Tswana overlordship, there were some occasions on which ambivalence, tension and uneasiness turned into open conflicts and confrontation. Although not so many in number, they are significant because they show that the dikgosi of the colonial era began to rely less on amicable incorporation and more on coercion. A case in point is the Kalanga, living scattered in a number of small communities in a region of northeast Botswana into which the Bangwato expanded. Werbner has compared the Kalanga to the Tswana, describing both as ‘super-tribes’: having ‘neither political community nor territory, [they] emerged as the broader category of culturally related people, widely spread in tribes and their diasporas, both rural and urban’ (Werbner 2002b: 733). In addition, both contained peoples of diverse origins from the outset (e.g. Ramsay 1987: 74). Sociopolitically, however, the Kalanga and the Tswana appear to have differed radically from one another. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the northern Tswana were organized in increasingly centralized polities while at the same time expanding their territories; Kalanga-speaking groups by contrast formed small ‘headmanships’ scattered throughout the northeast of present-day Botswana.20 In the Tswana manner of expansion, these settlements were incorporated into the Ngwato morafe in the latter part of the nineteenth century as a result of refugee movement and conquest.21 They thus came under the rule of the Ngwato kgosi Khama III (r. 1872/5–1923), who accommodated them peacefully for a long period of time (van Binsbergen 1994: 675) and included their leaders in his government.

A major shift came with the regency of Tshekedi (r. 1926–1949). Whereas Kgosi Khama III had allowed the Kalanga a measure of self-government, Tshekedi installed his own retainers as governors of the region and diminished significantly the existing Kalanga authority figures. This move initiated a protracted struggle, during which the Bangwato ruling group used considerable violence in their efforts to subjugate the Kalanga. Indeed, their treatment of the Kalanga was so harsh that at times British support was given only reluctantly (see Ramsay 1987: 77ff.). The British saw all too well that continued resistance by the substantial Kalanga minority22 within the Bangwato-controlled morafe threatened the interests of the colonial state and, especially, their practice of indirect rule.

The shift by the Tswana ruling groups to exercise more coercion while under British protection, engendered resentment among many subject communities. The vast majority, however, were too small and weak to react by resistance.23 Even the larger ones reluctantly submitted to Tswana rule – for example the BaKaa, who were located in the ‘native reserve’ ruled by the Tswana community of BaKgatla (baga-Kgafela). Kooijman (1978: 13–14) explains that ‘[a]lthough they felt resentment, the Kaa feared the consequences of ignoring the Kgatla chief's call too much to demur openly’, except on one occasion in 1927 when a young man, Phesudi, was installed as their leader. During the ceremony he wore a leopard skin, a true symbol of supreme authority, and expressed his intent of claiming ‘full independence from the BaKgatla’. However, shortly afterwards Phesudi died, and this was perceived as an occult attack effected by the personal involvement of the BaKgatla kgosi: ‘to the Kaa it was a stern warning that they were to obey Kgatla authority or otherwise suffer consequences of dire misfortune’ (Kooijman 1978: 15).

These events substantiate the growing strength of the ruling Tswana communities during the colonial era. Calls for British intervention were required only in a few special cases such as the Kalanga-Ngwato conflict mentioned above. Another such case involved the BaKgatla-baga-Mmanaana in the Bangwaketse ‘native reserve’. This large Kgatla community had moved around the region for many decades without being able to gain control of a separate territory. Finally they were taken in by the Bangwaketse and installed at Moshupa some fifty kilometres north of the Bangwaketse royal town (Kanye). A series of conflicts between their leader and Kgosi Bathoen II of the Bangwaketse, initiated in the early 1900s, culminated with the senior section of the Bakgatla ruling dynasty and many followers being exiled in 1933 to the neighbouring Kwena ‘native reserve’ when the British intervened with physical force (see Schapera 1942a: 21 and 25, cf. 1942b; Tselaesele 1978: 35). This particular intervention was no doubt due to the tenacity of the Kgatla leader at the time. However, the progressive polarization that brought the relationship to the brink of physical violence (Tselaesele 1978: 40) also reflects a growing tendency towards authoritarianism among Tswana rulers (see the following chapter).

A third case is that of the Babirwa whose leader tried, in the 1920s, to challenge the authority of Kgosi Khama III to remove them from their area, the background being that Khama had given this area to the British for sale of land to white farmers. The Babirwa resisted, only to experience that a Bangwato regiment (mophato) forced them out of their area and put fire to their houses. Their subsequent efforts to bring the case to court were jeopardized by the British who cooperated closely with Khama in a process that was concluded with the Babirwa leader being banished from the protectorate (see Ramsay 1987: 64ff.). This case illuminates that the British were quick to support the dikgosi when harsh physical violence was seen necessary, but there were very few occasions of this kind.

The dikgosi's heavy-handed behaviour was not only a matter of imposing their will on the subject communities within the merafe. It also owed a great deal to the authoritarian style and structure of the colonial state, which made the dikgosi responsible for extracting taxes and enforcing British rules and regulations. These were responsibilities they willingly took on since they were given a percentage of the tax collected. Imposed colonial state rules and regulation only reinforced their dominant position in relation to subject communities (see following chapter). Although these measures, perceived as oppressive, originated from the colonial state, subject communities reacted against the dikgosi rather than the British. In fact, the Bakgatla-baga-Mmanaana, the Bakaa, the Bayee and others wanted to eliminate Tswana kgosi domination by obtaining a direct relationship with the colonial power. The British always refused to accept such requests.

In conclusion, under the circumstances of the colonial state, the repressive character of the dominant Tswana intensified. Despite subject communities' resistance, the Tswana rulers prevailed because they could always appeal for British support and were provided violent measures if required. A multitude of – often tacit – repressive practices that developed during colonial times have, as we shall see in Chapter 5, been sustained in important respects under postcolonial conditions and have become integral to the modern state structures of social control. However, under these circumstances, I shall explain, major conflicts are emanating from contradictions of, on the one hand, Tswana domination and repressive practices in relation to minority communities, and, on the other hand, the modern state's virtues of equality and liberalism.

Reinforcing of the Tswana Merafe within the Colonial State

That the domination of the Tswana merafe triggered minority protest as late as some thirty years after independence, I take as an indication of how forcefully Tswana hegemony has been working at all times. The ways in which these protests manifested and were countered by agents of the state are a major issue of Chapter 5. Here I am concerned with the ways in which the dominant position of the ruling communities of the Tswana merafe recognized by the British was reinforced during colonial times by virtue of extensive delegation of power. The British had after all promised at the inception of the protectorate that the selected Tswana dikgosi 'might be left to govern their own tribes in their own fashion'.24

Always wanting to run the protectorate at minimal cost, the British established a very small colonial administration, headed by a resident commissioner whose office was in fact located outside the country – in the township of Mafeking, some twenty kilometres beyond the South African border. (The resident commissioner was referring to the British High Commissioner residing in Cape Town.) This meant that the day-to-day government of much of the country was left with the dikgosi and their respective ‘tribal administration’. The British authorized, I recall, the dikgosi to govern all the peoples (except Europeans) in their ‘reserves’. Moreover, in several official statements (see Schapera 1970: 51–52) the British asserted from the outset that the colonial administration should ‘respect any native laws or customs’ regulating ‘civil relations’. The secretary of state actually instructed the high commissioner to ‘confine the exercise of authority and the application of law, as far as possible, to whites, leaving Native Chiefs and those living under their tribal authority almost entirely alone’ (Schapera 1970: 52, italics added). When the colonial administration wanted to establish laws and other regulations, the high commissioner had the power of doing so in the form of ‘Proclamations’. Crucially, however, the British rather preferred to encourage the dikgosi to frame laws for their subjects (see Schapera 1943b: 9; 1970: 53). It is true, as we shall see in the following chapter, that around 1930 the British took a more active and critical line in relation to the dikgosi, being worried about their ostensibly ever-more-autocratic style of rule. Nevertheless, throughout the colonial era the British depended much upon the executive power of the dikgosi in relation to the population within their respective ‘reserves’ and continued to feature as authorities with wide-ranging executive powers.

The increasing array of activities undertaken by the dikgosi and their respective governments is reflected in systematic written records of their decision making. For example, Kgosi Seepapitso III of the Bangwaketse (r. 1910–1916) compiled comprehensive accounts that later on were published by Schapera (1947b) and examined by Roberts (1991: 173). Roberts has identified the various fields in which dikgosi exercised their authority, including: ‘the agricultural cycle; control over access to agricultural land; the regulation of population densities in residential areas; the regulation of family life; the management of education; the organisation of public works such as roads and construction, and the eradication of noxious weeds; attempts to control Christian sects; regulation of the activities of the Ngwaketse medico-religious specialists (dingaka); control of money-lending; and the management of stray cattle’.

As this suggests, many of the dikgosi readily operated as agents of Western modernity, extensively confirmed by Schapera's (1970) ‘Tribal Innovators’. In the dikgosi's effort to conduct the administration of their respective ‘reserves’, they also developed a small administration, staffed with clerks who, amongst others, made written records of political decisions and court judgements. This was, however, not a radical break with the past. As Wylie (1990: 55) states, the northern Tswana dikgosi changed to ‘govern with the aid of salaried bureaucrats who were accountable to him alone’. The point is that the dikgosi could only operate powerfully in the interest of the British (and themselves) by maintaining their authority in relation to the morafe. This meant that they had to exercise authority continuously in the context of the kgotla and cultivate networks of political support amongst powerful dikgosana and other authority figures. A kgosi who repeatedly acted in disagreement with his subjects would not last long (see Chapter 6). That the two most prominent indigenous rulers during the colonial era – Kgosi Bathoen II of the Bangwaketse and the regent Tshekedi of the Bangwato – developed particularly forceful leaderships did not depend upon British support alone. As we shall see in the following chapter, the relationship between these two dikgosi and the British was at times ridden by serious conflicts and was always ambivalent.

Of course, it is questionable the extent to which the popular meetings in the kgotla (lebatla, pitso) under the presidency of the kgosi- with a highly inclusive assemblage of the adult male sections of the population (see Schapera 1984: 82) – were operated in a ‘democratic’ way in a modern, Western sense (see Chapter 6). It is nevertheless crucial that vast sections of the population were regularly gathered in the royal kgotla and exposed to the exercise of kgosi authority as the apex of the hierarchical structure of royal councillors (bagakolodi, singl. mogakolodi) and dikgosana25 of all the wards comprising the morafe. This exercise of authority was, to missionaries and other Westerners, readily conceived as mundane, secular practices of public debate ended by the kgosi's concluding statement. But, as I shall explain in Chapter 4, the process itself – in the discursive field of the kgotla – had significance far beyond resolving pragmatically the issue at hand in a straight forward Western sense. In brief, the debates in this discursive field – which often go on for hours and even days – ritualized the rich symbolism underpinning the hierarchical order of the merafe. They hence asserted the eminence of the Tswana ruling group surrounding its apex – the kgosi – who, as the incumbent of the bogosi and the principal custodian of ancestral morality, gave this particular hierarchy a cosmological anchorage.

The consequent reenforcement of the dominant position of the Tswana was gaining further momentum by the ever-more-present, larger world that impelled the dikgosi to secure societal control by means of legislation. Prior to legislation the dikgosi consulted extensively with their bagakolodi, dikgosana and the merafe at large in the context of the kgotla. Schapera's (1943b) extensive survey of the laws (melao) framed by Tswana rulers since the mid-eighteenth century shows how legislative activity intensified progressively during the colonial era. This development had a significant bearing on the dominant Tswana groups' exercise of authority in relation to subject communities as the legislative debates in the royal kgotla also included their leaders. Patently, they were brought into a discourse governed by the dominant Tswana which was leading up to the kgosi's decision, anchored in the Tswana royal ancestorhood.