Читать книгу The State and the Social - Ørnulf Gulbrandsen - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

TSWANA CONSOLIDATION WITHIN

THE COLONIAL STATE

Development of a Postcolonial State Embryo

In view of the ways in which the British established supremacy as a rather distant power, it is not surprising that the peoples of the Bechuanaland Protectorate did not develop any strong notion of colonial power as repressive. Of course, the imposition of tax and levies and other requirements were received negatively. Yet many of my old friends and acquaintances on labour migration to South Africa (which was very substantial for almost a hundred years, until the mid-1980s1) recalled a strong contrast between the protectorate and the increasingly repressive, racist regime of South Africa. This difference finds one of its most important expressions in the fact that while peoples of the surrounding states had to engage in violent freedom fights to get rid of the respective racist regimes, the peoples of the protectorate received independence long before the others in a highly smooth and nonviolent way. The colonial state faded out in 1966 as nonviolently as it had captured the population into its structures of domination some eighty years earlier.

This disparity illuminates that, as John Comaroff (2002: 126) reminds us, there is nothing like the colonial state in Africa: ‘colonial regimes contrasted widely’. He argues that instead of conceiving such regimes in terms of ‘generic properties’, we should envisage ‘an ensemble of generative processes’ (2002: 124). Such a processual approach will help to identify, with a much higher degree of specificity, the diversity of colonial regimes. Within the present limits I shall pursue this approach from the point of view that the colonial state in the Bechuanaland Protectorate was not reducible to the British Administration, although it relied, as we have seen, on some dominant coercive powers under its command. Rather, the colonial state should be seen as an assemblage of interrelated regimes in which the officially recognized dikgosi held a key position.

As shown in the preceding chapter, each of the merafe might be seen as a hierarchy of regimes, centred in the respective lekgotla, with the royal office at its apex. The royal office was in turn subject to the British Administration. However, the latter depended on the chain of command vested in the hierarchies of authority within the merafe. At the same time the former depended on the administration should their authority ever be seriously challenged. In what follows I shall first pursue the argument initiated in the preceding chapter: that on the whole this situation had the effect of strengthening the structures of authority relations and domination within each of the merafe recognized by the British. In fact I shall identify significant processes that worked to amalgamate the power structures of the merafe – structures that proved, as we shall see in the following chapter, also to be very sustainable under the conditions of the modern, postcolonial state of Botswana.

However, this is not to say that consent and harmony prevailed throughout the eighty years of the protectorate's existence. In this chapter I shall explain how conflicts and tensions evolved both between the dikgosi and the British and between the dikgosi and their subjects. These conflicts and tensions developed greatly under the impact of Western modernity and raise a major conundrum: under these circumstances, how could a quite unified group of people emerge, often at odds with the dikgosi, which was capable of negotiating decolonization and establishing firm political control over the postcolonial state? Furthermore, I want to answer this question: how could such a group, strong adherents of Western liberalism, the market economy and electoral democracy, succeed in curtailing the powers of the (mostly resistant) rulers of the Tswana merafe and incorporating them into the structures of the postcolonial state, far more tightly and powerfully than the British had ever attempted to do?

Colonial State Transformations: Conflicts and Mutual Dependency between the Dikgosi and the Colonial Power

It is true that with the establishment of British overlordship the rulers of the Northern Tswana merafe lost their absolute sovereignty, since some limitations were placed on their judicial and legislative powers. Nevertheless, Schapera has asserted that ‘the events of 1895–96 greatly enhanced the personal powers of traditional rulers in the Bechuanaland Protectorate’ (quoted in Parsons 1998: 254). The long-term significance of these developments has also been noted by Gillett, who maintains that ‘under the Protectorate the Tswana chiefs [dikgosi] enjoyed almost unchallenged power’ (Gillett 1973: 180).2 Such statements reflect the British policy of leaving the dikgosi to govern their respective merafe with minimal interference until some forty-five years after the establishment of the colonial state.

The extensive practice of indirect rule over such a long period of time amply demonstrates the capacity of the dikgosi and the hierarchies of their respective merafe to keep the population in the societal fold. Nevertheless, in due course the relationship between the dikgosi and the colonial administration became increasingly ambivalent and at times riddled by serious conflicts. Although the authority of the dikgosi and the strength of their polities still enabled the British to run the protectorate at minimal administrative and financial cost, the dikgosi were increasingly perceived as dictatorial. They were seen as operating highly autocratically in relation to their subjects. The trend on the British side in relation to their possessions was, by contrast, to introduce Western principles of legal rationality and state of justice. These strongly conflicting orientations came out fully around 1930.

For example, in 1929 an important resident commissioner stated in his diary: ‘[The dikgosi] practically do as they like – punish, fine, tax and generally play pay hell. Of course their subjects hate them but daren't complain to us; if they did their lives would be made impossible’ (Parsons and Crowder 1988: 4). Other contemporary statements by representatives of the colonial administration similarly portray these rulers as rather autocratic. For example, a resident magistrate stationed in the Bangwaketse capital of Kanye reported that Kgosi Bathoen II of the Bangwaketse (r. 1928–69)

is very obstinate and inclined to be antagonistic in matters connected with the Administration…Morally, Bathoen is rather a low type of native…being legally married to an educated woman, and at the same time living openly with his concubine. He is disinterested in matters beneficial to the tribe unless he, personally, can benefit thereby, and considers everything from his own pecuniary standpoint. His councillors are young and inexperienced headmen of the Communist type; he takes little heed of his older and more reasonable me.3

Furthermore,

he is very selfish. If he requires labour for his own work, such labour is forthcoming, but if for the benefit of the Tribe he is apathetic.4

The autocratic tendencies of the dikgosi were of course very much a product of their privileged and protected position within the colonial state, reflecting indeed the British dependency upon the ways in which they had expanded their networks of power and captured vast subject communities into the structures of the colonial state (see preceding chapter). Furthermore, the range of executive powers of the rulers of the Tswana merafe selected and privileged by the British increased steadily as the political economy of the protectorate developed. Since it ‘was an explicit policy that the British Government had no interest in the country north of the Molopo…except as a road to the interior’ (Sillery 1974: 77), the Tswana were informed that they would have to bear the costs of the protectorate themselves. A hut tax system was thus enforced,5 from which the dikgosi benefited substantially since they received a 10 per cent share of whatever they collected, over and above funds received from a number of other sources.6 Significantly in the present context, the dikgosi retained their ‘customary’ privileges, including the mobilization of age regiments (mephato, singl. mophato) and draught power for the cultivation of their large fields, as well as the receipt of hunting spoils (sehuba), ‘thanksgiving’ corn after harvest from every household (dikgafela) and, most importantly, all the unclaimed stray cattle collected in their respective territories (matimela).

All the wealth thus aggregating in the royal household was customarily justified by the virtues associated with the kgosi as motswadintle (‘the one from whom good things are coming’, see Gulbrandsen 1995 and Chapter 5, this volume). By right, therefore, he should be rich – ideally as the guarantee of everybody's welfare. His wealth was also seen as a major condition for his independence and incorruptibility as a ruler. However, as the British contributed strongly to reinforcing the dikgosi's powers, the dikgosi were not dependent on extensive networks of power by dispensing cattle widely for establishing cattle clientship (cf. Chapter 1). At most, their resources were used to ensure the support of their most important political retainers in relation to the royal centre. Moreover, as labour migration to South Africa provided most ordinary families with a stable source of basic subsistence requirements (see Schapera 1947a), there was less need to dispense grain from the royal granary during times of poor harvest.

All this meant that the dikgosi retained a number of economic sources throughout the colonial era which facilitated the accumulation of wealth – mainly in the form of cattle – that progressively attained the de facto character of private property. The British became increasingly disturbed by the dikgosi's expropriation of funds considered by the colonial power to be destined for ‘tribal’ purposes. They first attempted to separate the dikgosi's ‘purse’ from that of the tribal treasury by establishing what was known as the Native Fund. In a major administrative reform dating from 1934, it was stated that ‘[the] chief could no longer impose tribal levies without written approval from the Resident Commissioner and without agreement of the tribe in the kgotla' (Colclough and McCarthy 1980: 25). Nevertheless, although this proclamation managed to a certain extent to separate public resources from those to be held by the kgosi personally, considerable uncertainty remained over what belonged to the tribe and what was the kgosi's property.3 I shall pursue the issue of the dikgosi's apparent avarice in the subsequent section.

The institution of a ‘Native Fund’ reflected a broader British concern about the dikgosi's alleged abuse of power, a concern which should be seen in the context of the colonial empire. First, after World War I, the British initiated a revision of their previous methods of indirect rule that was extended to the Bechuanaland Protectorate in the 1930s. Secondly, at this time there appeared highly critical reports in Britain attacking prolonged neglect on the part of the Protectorate Administration that had resulted in stagnation, extreme backwardness and highly autocratic chiefs. It was argued, for example, that ‘colonial authorities had failed to bring traditional institutions in Bechuanaland into conformity “with the essential requirements of a modern civilized administration”’ (Picard 1987: 49). In addition to such broader concerns, the administration had experienced difficulties with dikgosi seen to be incompetent or otherwise unsuitable for their office: the most serious of these concerned Kgosi Sebele II of the Bakwena, who was, as we shall see in the following section, dethroned by the administration and exiled to Ghanzi in the extreme west of the protectorate.

This was the beginning of a long-term process, lasting through most of the colonial era, by which dikgosi and agents of the colonial state repeatedly confronted each other over attempts to check the dikgosi's powers by means of radical changes in the government of the merafe. I shall review some of the most important ones in order to identify processes and structural conditions that explain why the dikgosi nevertheless largely maintained – even in certain respects enhanced – their position as supreme authority figures and strengthened the structures of their respective polities.

The determination of the British to make radical reforms found a major expression in two proclamations issued by the high commissioner in 1934. These proclamations were both introduced by reference to the Order-in-Council of 9 May 1891 whereby ‘the High Commissioner is empowered on His Majesty's behalf to exercise all powers and jurisdiction which Her late Majesty Queen Victoria at any time before or after the date of that Order had or might have within the territory of the Bechuanaland Protectorate’. It was conceded that proclamations issued by the high commissioner ‘shall respect any native laws and customs by which civil relations of any Native Chiefs, tribes or populations under His Majesty's protection are now regulated’. There was, however, one important caveat: respect was to be accorded only insofar as native laws and customs were not ‘incompatible with the due exercise of His Majesty's power and jurisdiction’.7 Motivated by the experience of allegedly autocratic, incompetent or otherwise unsuitable dikgosi – the most obvious case being the deposition of Kgosi Sebele II of the Bakwena, mentioned above (see Ramsay 1987: 39f.) – the resident commissioner argued that ‘it is essential that we should legalise the position of the chief…there must be provisions for the Government to recognise the Chief and his suitability for the chieftainship in the interest of the whole tribe’.8

The first proclamation (No. 74 of 1934) stipulated channels through which ‘the tribe’ might articulate dissatisfaction with their kgosi as well as proper procedures to hear the kgosi's defence before the administration made its decision in such matters. The dikgosi rejected this and other provisions in the proclamations on the grounds that these provisions fundamentally disagreed with the Order-in-Council of 9 May 1891. As described above, this document authorized the high commissioner to legislate by proclamation; however, he was restricted by the condition that he should, I reiterate, respect any native laws or customs regulating civil relations (see Schapera 1970: 51). Thus, the new rules for the recognition and instalment of a kgosi were perceived as being in basic disagreement with the Tswana maxim Bogosi boa tsaleloa, gab o loeloe (‘A man should be born for the kingship, not fight for it’). In cases of abuse of power or misconduct in office, it was argued, they had their own procedures: Kgosi ke kgosi ka morafe (‘The kgosi is king by virtue of the tribe’).

The dikgosi feared that they had now been relegated to the lower end of the colonial state hierarchy, supervised by and committed to report to the local resident magistrate. This was obviously intolerable for powerful figures who were accustomed to being recognized by their people according to the dictum Kgosi ke modingwana, ga e sebjwe (‘The kgosi is a little god, no evil must be spoken of him’) and whose authority was sustained by another important maxim: Letswe la kgosi ke molao (‘The kgosi's word is law’). They had also been accustomed to relating directly to the high commissioner. In one of my conversations with Kgosi Bathoen II he stated that to him the resident magistrate was a foreign representative and ‘not my superior’ (cf. Picard 1987: 51).9

Furthermore, when the proclamation of 1934 mentioned above required the dikgosi to establish ‘Tribal Councils’ comprising named members with whom the dikgosi were obliged to consult, it conflicted both with a kgosi's customary privilege to consult whomever he wanted and with his commitment to give due importance to the views of his subjects as expressed in the public sphere of the kgotla where the ‘entire morafe’ (i.e. all adult men) were entitled to participate. Both proclamations, if fully implemented, would probably have undermined the popular forum of the kgotla, idealized by people as the place where all authority figures should make their operations transparent (see Chapter 8). The administration, however, saw the kgotla as patently open to manipulation by the dikgosi and thus conducive to their alleged exercise of autocracy.10 They wanted to establish identifiable and thus accountable bodies that were less dependent on the dikgosi.11

The aim of ensuring legal-rational accountability was particularly apparent in the ‘Natives Tribunal Proclamation’ (No. 75 of 1934), which established that the courts of the merafe were to be divided into two classes of tribunals, designated as Senior Tribal Tribunals (presided over by the kgosi) and Junior Native tribunals. According to this system, ward and descent-group courts were no longer judged competent to pass legally binding sentences. The tribunals were to be composed of identifiable councillors selected from the Tribal Council and nominated by the kgosi, and the councillors were to be paid a fixed salary. The dikgosi refused to comply with the requirement to elect named members to the tribunals, rhetorically asking: ‘If anybody is to be paid are we going to pay all the Chief's Councillors, which implies the whole tribe?’12

The dikgosi were obliged to ensure that written records of their proceedings were available for inspection by the local magistrate, in part to ensure adherence to the principle of equality before the law. It had been a common practice for quite some time to keep written court records, so the request was not in itself controversial. What provoked the dikgosi was the underlying intention to facilitate the appeal of cases from the Senior Tribunals, over which the dikgosi should have presided, to the local resident magistrate court. These provisions, which went together with the recognition of ‘native laws and customs’ only insofar as they did not contradict the legislation of the colonial power, epitomized the subjection of the dikgosi – both as legislators and as judges – to the administration.

Behind the strong resistance towards the proclamations lay also the fear of annexation: in the last session of the Native Advisory Council13 at which the two proclamations of 1934 were debated, the following resolution was addressed to the high commissioner: ‘This meeting of Chiefs and Councillors present on behalf of their respective Tribes of the Bechuanaland Protectorate records its protest and objection to the incorporation of their Territory into the Union of South Africa’14 (see preceding chapter). Kgosi Tshekedi, regent of the Bangwato between 1926 and 194915 and always on the alert in relation to the question of annexation, had evidently been ‘particularly alarmed by the similarities between the proclamations and the South African Native Administration Proclamation No 38 of 1927’ (Wylie 1990: 113). Similarly, Kgosi Bathoen II of the Bangwaketse indicated in several of our conversations that they all ‘saw the writing on the wall’, but could do nothing at this stage except state their objections, since the council was advisory only.16 The resident commissioner and the dikgosi (with the Tswana councillors) failed to reconcile their differences on the matter.17

The two most forceful dikgosi at the time, Kgosi Bathoen II of Bangwaketse and Kgosi Tshekedi of Bangwato, were the leading figures in further efforts to have the proclamations abandoned. In the typical Tswana manner, they brought their case to court, suing the high commissioner by invoking, among other things, precisely the same Order-in-Council of 1891 with which the proclamations had been introduced (see above). In particular, they claimed that the high commissioner had legislated in contradiction of the rights accorded their respective tribes by treaty with Great Britain. The judgement, however, lay in the hands of the British themselves: a special court was set up that ruled against the dikgosi, stating that a treaty could not prevent His Majesty from legislating, and that as a result the administration had ‘unfettered and unlimited power to legislate for the government and administration of justice among the tribes of the Bechuanaland Protectorate’.18 Thus although the dikgosi invoked the ‘treaty’ their ancestors had made with the British in support of their claim that the ‘protection’ was a matter of partnership,19 the judgement made it utterly clear that the rulers of the Tswana merafe in the protectorate were subject to the orders of the colonial state.

However, as Wylie has observed (1990: 115), ‘[t]he administration's victory was symbolic’ in the sense that it was never really implemented. For example, tribal councils and tribunals were only partially established; the dikgosi kept on the customary practices of consultation (kgakololano), particularly in relation to their selected councillors and the kgotla. The people at large did not experience any significant changes: they continued to respect the judgements made in descent-group and ward courts, which were occasionally appealed to the royal court, but very seldom further to the British Magistrate Court.

This also meant that the dikgosi continued to run their merafe in autocratic ways. Also, even though the colonial power had now firmly established that the dikgosi were under the full legislative authority of the colonial state, the British still rarely interfered with their rule. In fact, ‘the chief's right to legislate independently was still officially recognised; and, as in the past, the Administration often preferred to advise, not to order, him to enact measures it favoured’ (Schapera 1970: 63, see also Jeppe 1974: 138). Furthermore, the minutes from the Bechuanaland Protectorate Native Advisory Council leave the strong impression of a generally cooperative relationship between the resident commissioner and the dikgosi (see Gabasiane and Molokomme 1987: 162–63). The controversies surrounding the proclamations of 1934 stand out as exceptional.20

It is therefore difficult to agree that ‘a series of colonial proclamations and ordinances…undermined the institution of chiefship’ (Vaughan 2003: 28) or that ‘the cumulation of multiple acts of British authority and the pervasive influence of commercialisation served to undermine the morafe as a system of rule’ (Peters 1994: 42). As long as such claims are not substantiated by an examination of the real political impact of the proclamations on the authority of the dikgosi and the hierarchies of authority relations over which they presided, we cannot simply assume that the British right to issue proclamations had an undermining effect. First, the British often preferred, I repeat, to let the dikgosi legislate (see Chapter 1), and if they wanted to legislate themselves, the dikgosi were usually thoroughly consulted in the Native/African Advisory Council (see Makgala 2010: 60), as is abundantly evidenced by the extensive minutes from the meetings. Secondly, it can also be argued that proclamations might increase the dikgosi's authority since they expanded the field of their exercising jurisdiction – an activity central to the reproduction and strengthening, as I argued in the preceding chapter, both of their authority and of their respective merafe's sociopolitical order.

It is tempting to suggest, therefore, that in the long run the dikgosi triumphed in important respects. This point is underscored by the arrival of two new proclamations in 1943 by which both the tribal councils and the tribunals were abandoned. Moreover, ‘the list of offences excluded from the jurisdiction of the Courts is now reduced to cases in which a person is charged with an offence punishable by death or imprisonment for life’ (Hailey 1953: 226), a change which largely restored the authority of the dikgosi to its original form (cf. Ashton 1947: 239).21

The increasingly relaxed attitude of the British to implement reforms stipulated in the proclamations of 1934 which might be seen as the background of the prevailing uncertainty – virtually throughout the colonial era – about whether to hand the protectorate over to the Union of South Africa, militated against implementing a reform that would have implied substantial costs. More basically, as reflected in a British official assessment, in due course the British recognized that it was not a straightforward matter to impose radical changes on the indigenous institutions of authority. In view of the colonial state's heavy reliance on these institutions, it is no surprise that it was criticized. ‘[I]n insisting on the establishment of a formally constituted Tribal Council and of Tribunals of a fixed composition to take the place of traditional trial by Kgotla, the law made a radical change in some of the most characteristic institutions of the Bechuana people…the people saw a menace to a system of trial to which they were as deeply attached as is a Briton to the procedure of trial by jury’ (Hailey 1953: 222).22

With some important exceptions, which I shall address subsequently in this chapter, the pragmatics of extensive indirect rule lasted virtually to the end of the colonial era as suggested, for example, by a highly critical observer of dikgosi's rule during the final decades of the colonial era, Botswana's former state president, Quett Masire. He clashed with Kgosi Bathoen II at several occasions (see below) and came to realize how protected Kgosi Bathoen actually was by the British, reflecting their need ‘to reinforce the powers of the chief in their method of controlling, or ruling, the people’ (Masire 2006: 259). That there was a mutuality of dependency – despite the ambivalence, tensions and conflicts over the years – between the dikgosi and the British is curiously demonstrated in Photo 3, where the two major Tswana figures of the colonial era – Bathoen and Tshekedi – are expecting the British royal family in British uniforms.

Finally, this also means that in relation to the conflicting relationship between the distinctive Tswana principles of politicojural practice and the ideals of Western bureaucratic rationality, the British made great concessions to the Tswana mode of exercising authority. Their rationale for considering another line – that of reconstructing indigenous institutions in line with modern principles of bureaucracy – was obviously reflecting a sense of losing control of the dikgosi, being perceived as increasingly autocratic and even exterior to the order of the colonial state.

Yet, in due course, they certainly came to realize that to challenge these authority figures more than necessary might well make them – and their institutions – less integral to the colonial state, creating potentialities of forces of a rhizomic kind. The central point is that the strengthening of the authority of the dikgosi under the British wing was, as I have explained, much a matter of the progressive expansion of the power structures radiating from the bogosi of the officially recognized Tswana merafe. As suggested by Hailey's statement above, the British came to realize how strongly these structures – which they had themselves contributed much to reinforce – were anchored in the indigenous cultural construction of authority, upon which the British always remained dependent. In other words, the British had to realize that with the extensive practice of indirect rule, they had given rise to a colonial state highly dependent on instruments of government of mainly a pre-modern kind, whose major agencies fiercely resisted transformations towards modern, legal-rational institutions. However, at the same time, the dikgosi depended upon the colonial state as a source of power – a mutual dependency prevailed in important respects (Ashton 1947: 238). Only in some few instances did the colonial administration intervene with harsh measures in relation to Tswana royal centres, examples of which we shall see in the following sections.

Illustration 3. Regent of Bangwato, Kgosi Tshekedi (left) wearing a uniform of Royal House Guards Blue acquired by his father (Kgosi Khama III) during the three dikgosi's visit to England in 1895 (Parsons 1998) and Kgosi Bathoen II (right) of Bangwaketse wearing the scarlet uniform of the Dragoon Guards presented to his grandfather (Kgosi Bathoen I) by Queen Victoria on the same visit to England. They are seen waiting for the arrival of the British royal family in the Bechuanaland Protectorate on 17 April 1947. Courtesy of Associated Press.

Issues of modernity vs traditionalism at Tswana royal centres

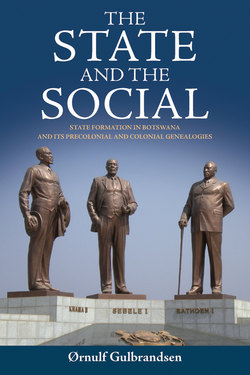

The dikgosi's distaste for Western, ‘rational’ principles and practices of government and administration of justice does not mean that they held on to customary practices and resisted modernity in all respects. On the contrary, as already suggested in Chapter 1, in their actual political practice within the frame of their institutions, many of them represented driving forces in implementing many smaller and larger reforms in positive response to the progressive arrival of Western modernity. The three dikgosi on the cover of this volume – Bathoen I, Khama III and Sechele I – featured already before the turn of the century in Western suits which soon became the daily dress of men of authority in the kgotla context. This practice was adopted under the impact of the evangelizing missionaries as a prominent sign of being a civilized (rutega) person. And in such guise the dikgosi took, I recall, Britain with great positive surprise when traveling across the country for gaining popular support for their cause (see Chapter 1, cf. Parsons 1988). The acceptance of many aspects of Western modernity became even more apparent as the succeeding dikgosi acted upon the European impacts in ways that are reflected in Schapera's (1970) notion of ‘tribal innovators’.

Nevertheless, in Tswana parlance there is a distinction between Setswana (Tswana ways) versus Sekgoa (the ways of the white people). Comaroff and Comaroff (1991: 212ff.) have examined thoroughly the complexity of the Setswana-Sekgoa interface in the case of the Southern Tswana in the South African context. In the present case I am concerned with the significance of these categories in terms of distinct and conflicting political identities at the royal centre of Tswana polities. That is, conflicting political identities entailing factionalism challenging the ruler.

In the preceding chapter I discussed the conflicts surrounding the dikgosi's acceptance of Christianity and the presence of an evangelizing missionary, forming a church congregation. At an early stage, I explained, there was clearly a Christian vs. non-Christian divide surrounding the royal office. This was particularly dramatic in the case of Kgama III and his father Sekgoma I before Kgama defeated his father and initiated his long reign in 1875. At such an early stage, there were also serious conflicts related to the arrival of Christianity at the royal centres of the Bakwena and Bangwaketse (Gulbrandsen 1993a: 49ff.) as well as the Batawana (Tlou 1973, 1985: 99ff.). Moreover, I explained, there then emerged conflicts between missionary churches and so-called independent Christian church movements that appealed to many people because of their greater tolerance toward indigenous ritual and social practices. These movements were often fiercely rejected by not only the dikgosi but also to a great extent the ruling elites because of, I recall, the perceived threat represented by these movements to the order on which they all basically depended. For these elites, it meant that they in due course had to comply with and impose the missionary requirement of abandoning important ritual and social practices.

However, popular resistance towards the abandonment of polygyny, bogadi (‘bridewealth’) and bogwera (initiation ritual) as well as prohibitions of alcoholic drinks prevailed as an undercurrent in many contexts. These changes had thus to be enforced continuously by Tswana rulers (Schapera 1970: Ch. 9). But in a few instances the dikgosi did not readily comply with missionary requirements of doing so. One intriguing case is that of Kgosi Sebele II of Bakwena (r. 1918–31).