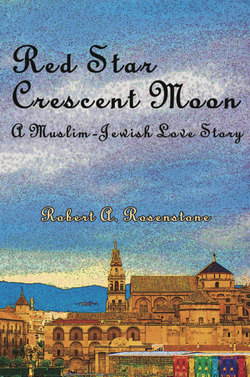

Читать книгу Red Star, Crescent Moon: A Muslim-Jewish Love Story - Robert A. Rosenstone - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 Benjamin

ОглавлениеWere I making a film and not writing a memoir, you would see a black Mercedes pull up in front of the stone bulk of a medieval tower as words on the lower right hand of the screen read: Cordoba, Spain. Five men wearing ski masks and carrying assault weapons burst out of the vehicle and race up its front steps two at a time, guns at the ready. Roughly they disarm the two uniformed guards at the entrance, then push them inside the building while their colleagues round up a bunch of cowering tourists, men with gray hair sticking out beneath baseball caps, bellies hanging over their belts, women in shorts, sandals, and straw hats, and herd them all into a cement basement room crammed with cardboard cartons, wooden crates, empty glass fronted display cases, stacks of posters advertising art works, ethnographic shows, tourist sites in Andalucia. Two of the masked men hurry up the winding staircase to the roof, haul down the red and gold Spanish flag, and run up a white banner with a green crescent moon in the upper left hand corner. As it flaps above them in the breeze, they pull off the masks, give each other high fives, and turn to gaze across the Guadalquivir River towards the bulk of the Grand Mosque and its soaring bell tower that once upon a time was a minaret

In this ancient medium of words, we have to make do with a headline, a newspaper story, and your imagination. On screen a director might fade to a slow panning shot across the expanse of a large European square surrounded by elegant, historic buildings. Again words tell us where we are: Plaza Mayor, Madrid. A late afternoon sun slips behind the rooftops in a blaze of digitally enhanced color, providing more than enough light to show it’s the end of a warm day, the men in short sleeve shirts, jackets over their arms, the women who aren’t wearing jeans clad in light skirts and blouses. The camera comes to rest on your narrator, wearing a wrinkled, khaki summer suit, leaning back against of one of the plaza’s four circular stone benches. Don’t expect me to describe myself. I’ll leave that daunting task to others. What I do know is that a camera eye view doesn’t provide full disclosure. My face may be slack and my eyes glazed but that wouldn’t let you see how full of thanks is my heart to all the gods in whom I don’t believe. Sixteen hours from LAX to Heathrow to Barajas, and the stuffed head and slight cough which follow any long flight do nothing to lower my spirits during these first hours back in my favorite country, where the Megastar known as TJ—”The Most Beautiful Man in Hollywood!”— is directing his first film, the script based upon my book, written two decades earlier in another life. I had a hand in the screenplay and have been officially hired to serve as historical consultant on the shoot.

Shadows ease across cobblestones. A hush falls over the great square. Or is that only a trick of memory, the product of an imagination attempting to make the entrance of our heroine seem more dramatic? I can say the following without fear of contradiction. The day tourists are drifting away, the night trippers have yet to come, and the indigenous hustlers who swarm the southeast corner day and night, peddling flags, maps, postcards, key chains; the bongo players who keep getting into arguments with the guitarists of long sideburns who fake flamenco riffs; the artists who draw charcoal portraits that make everyone look vaguely like a descendant of the Hapsburgs, with large and prominent jaws; the drug dealers who lurk in the surrounding arcades, wearing jeans with American advertising slogans stenciled on them, ready to sell you buds from the finest hemp plantations of the Rif Mountains – all those who normally make the plaza bustle are taking a break. Groups of them cluster in the far corners, passing around bottles of wine to prepare for the evening onslaught of tourists, teenagers, drunks, and druggies.

Like a character in a science fiction film, she materializes as if out of nowhere, beamed down from some sleek space craft hovering far above the planet. Or perhaps she slips through one of those worm holes in space, enters our world as the representative of a civilization centered in some far off galaxy in another dimension which we humans are incapable of perceiving. I don’t see her approach the bench, do not become aware of her until she eases onto it a few feet to my left, just beyond two young mothers who hold squirming babies in their arms. Next to her an elderly man, black beret on his head and blacker cigarette in his right hand, sits erect in a military posture. The left sleeve of his jacket is neatly pinned to his shoulder.

Her face doesn’t belong here.

That’s my first thought.

It belongs in a tale told by Scheherazade.

That’s my second.

I know what you’re thinking. These sound like lines written later, agonized over for months or perhaps jotted down just now. But they’re not. I can show them to you in a file created that very evening, May 15, 1996, composed on my Toshiba laptop in room 736 of the Palace Hotel.

Putting his cigarette on the edge of the bench, the smoker touches his beret with his one hand in a gesture left over from an age more gallant than ours.

Sorry, I don’t speak Spanish.

I think that’s what I hear. Her voice is so soft I can barely make out the words but the intonations are those of English.

The two mothers wrestle their kids into strollers and push off while I feverishly search my jet lagged brain for an opener less worn than Haven’t we? What’s a? Can you? Nothing occurs before a young man arrives to help me out. Even in the fading light you can see the signs of addiction—the bad skin, shifty eyes, erratic stride, shirt sleeves buttoned to the wrist when other youngsters stroll about in tee shirts and tank tops. He stops in front of her and begins a story that, as my father would have said, is as old as the hills. Maybe older. She has such a kind face. Someone has stolen the backpack with his wallet. He’s from Holland. A college graduate. Trying to get in touch with his parents to bail him out, but they’re on vacation in Italy and he hasn’t yet been able to reach them. If she could lend him some pesetas he’ll pay them back as soon as the money arrives. Tomorrow. The next day at the latest. He takes an oath. He puts his hand on his heart.

Excuse me, I find myself saying. That’s the oldest con in the world.

She glances my way. Dark eyes make me aware of the movement of my heart. She opens her purse.

If his story is true I’m the king of Spain.

She hands over a couple of bills. He looks at me, smiles, thanks her with a deep bow and a sweep of the right hand as if he were a musketeer holding an enormous, feathered hat, then walks towards an archway that leads out of the plaza without looking back. We stare after him while the one armed man stubs out his cigarette, stands up, again touches his beret, says Buenas tardes, and strolls into the gathering darkness.

When I first came here decades ago, I say, You used to see lots of men like that, men without limbs or hands. Inutiles de guerra. The Spanish term is tricky to translate. Useless because of war. That’s pretty close. They were shot up during the great civil war here back in the thirties. Not too many around these days.

War is horrible, she says.

The huge paintings of nudes that sprawl across the facade of the Casa de Panaderia are becoming difficult to see in the fading light. Bulbs strung on wires around the outdoor cafes edging the square come on slowly, and the iron lamp above the bench sputters into a glow. A phalanx of Asian women holding colorful parasols aloft stride towards the nearby bronze statue of a man on horseback and arrange themselves in ranks for photos in front of its high pedestal.

Are you interested in knowing about that guy on the horse? I ask.

A pause that probably seems longer than it is and she says: Some king or other, I suppose.

Right you are! Felipe Tres. Phillip the Third. Not a very important king as kings go, and as Groucho or my father might have said, he probably should have gone. Eventually he did, but not before getting this plaza built. It was planned during the reign of his father, but planning and building are two different things, especially considering the state of the Spanish economy in the seventeenth century or almost any other. You can see here the beginning of planning, the notion a city can be thought into being. People came from everywhere to marvel at its spaciousness and beauty. From France, Germany, from far away as Russia. On the ground level were shops, bakers, butchers, chandlers, merchants of all sorts, but the apartments on the upper floors went to the nobles and the very rich, to relatives and friends of the king as a refuge from the boredom of their country estates. This became the center of the city. The place to see and be seen. Where you went for the great public spectacles—bullfights, horse races, executions—you name it, they had it in the Plaza Mayor. Along with a special kind of entertainment invented in Spain: the auto da fe. Act of Faith. During the Inquisition these huge public spectacles were held right here. Hundreds of heretics dragged into the square and flogged in front of cheering crowds, then hauled off and hanged for the sins of worshiping the wrong God, or the right God with the wrong name. There’s a painting in the Prado which shows an auto da fe in full swing. Just about where we sit, you can see people being whipped. You’ll recognize the buildings. They haven’t changed much. It’s on the ground floor of the museum, near the north stairwell.

Are you an artist? she asks in a neutral voice that may be due to natural caution but seems to partake of wariness I have seen in the eyes of others following one of my impromptu historical lectures.

No, I’m a writer. I used to be a professor of history, but now I’m a writer. Benjamin is my name. Benjamin Redstone at your service.

Out of what old costume drama did that phrase escape? But something about this woman seems to demand such language. She holds out her right hand. Slender, elegant fingers (and if they weren’t do you’d think I’d admit it here?), well shaped nails colored a soft pink. I dare not hold them for more than an instant.

Alison, she says.

That name doesn’t go with your face.

Her eyes make me regret the words that blurt from my lips. For a long moment we watch the Asian women shift places and take yet more photos, then form into ranks, and march towards the south archway and out of the plaza.

I suppose you’re right, she says at last, her voice almost confidential. My name isn’t really Alison. But so many people mispronounce my god given name that I get fed up correcting them. These days I only use it with friends and family. It’s Aisha. My real name is Aisha.

The last wife of the Prophet, I say. The youngest and most favored.

Her eyes open wide.

How do you know that?

For the first time in the more than quarter century since graduation, a college course actually pays off. God bless Berkeley’s social science requirement, the anthropology department’s course in Comparative Religion, and the lectures of Professor Lance Thorneycroft, a specialist in the cultures of native Americans who devoted four hours to Navajo sweat lodges, six to Hopi shamans, and eight to the Kwakiutl of the North Coast. Christianity and Judaism each received two hours. Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam got one. The distribution didn’t faze us, for we particularly loved the prof’s stories about the potlatches of the Kwakiutl. Part of it was the name, which my buddies and I liked to shout back and forth, emphasizing the first syllable, making us sound, or so we thought, like ducks calling to one another. We offspring of immigrant families on hustle in the new world found something enormously fascinating about a tribe of people who burned their possessions in public to express disdain for the material world.

I can’t remember what word the professor used for the religion, but the title of our textbook was Mohammedanism. I know for certain because it still sits on my bookshelf a few feet away from where I write, with its short biography of the Prophet, a brief history of the religion spanning thirteen hundred years, and selections from the Koran which took me into a world as alien as the one in the chapters of When the Jewish People Was Young, the book I was forced to study during my two year Sunday School career, a volume full of the trials, heroes, prophets, and kings of the ancient Hebrews and their angry God with his tiresome and repetitious injunctions and threats. If he’s so Almighty, I remember thinking at the age of eight, if he can create the world in six days, I mean if he’s God and he knows everything, how come he doesn’t realize that people are going to trash his laws, so why doesn’t he relax and stop complaining and thundering so much? You can imagine that the stories of the Prophet and his many wives drew more than a few wisecracks from my friends and I, but if I could recall any of them, I wouldn’t dare disclose them even in a work of retrospection, for today our words would lead to public demonstrations, the burning of the American flag, angry calls for jihad, the raising of the national alert level a color or two.

I don’t, of course, say any of this to Aisha. Only that I studied Islam in a college course on religion. Only that I found it rather interesting.

How unusual, she replies. Most Americans know so little about Muslims and care even less. I wonder if it’s the same in Spain?

Pretty much, I say, without really knowing. So tell me, this is your first time here? First time in Madrid?

First time in Europe, she says.

Now there’s an assumption in what you say. An important assumption. Is Spain really part of Europe? That IS the question. Louie the Sixteenth of France said Europe ends at the Pyrenees. The Spanish say it begins there. Every ending is of course a beginning, so maybe they are both right. Come have a drink with me and I’ll tell you all about the controversy and everything else you need to know about Spain.

Aisha shakes her head. She’s not thirsty. She doesn’t have the time. She must get back to the hotel.

Don’t be hasty, I say. When I was a historian, Spain was one of my fields. If I can tell you about Felipe Tres and this plaza, think about how much I know about the rest of this country. I’ve been coming here for decades. Kings and queens, wars, traditions, art, music—I can lecture about them all. And if you’re not interested in history, and I wouldn’t blame you if you’re not, I can help you with tourist stuff, recommend restaurants, keep you away from overpriced clip joints and disappointing sights. An hour conversation and you’ll be able to dazzle friends with your vast knowledge of Spanish history and culture.

You do sound like a professor, she says. I never took much history but I always liked being a student. Except for the exams. I never liked exams.

No exam, I promise, touching my hand to my heart. Only a drink and a lecture on a topic of your choice.

One drink. One lecture. One short lecture, please. I don’t have much time.

I lead Aisha to table on the terrace of the closest café. Does she want a glass of wine? No thank you. Sherry? No. She prefers coffee, her brief responses spoken in a tender voice with one of those slight accents which suggest coital activities in some exotic land. I put aside my desire for a glass of sherry and order two café con leche.

What does one say to a Muslim woman? Beats me. I don’t remember ever talking to one before. Too bad I don’t know some jokes beginning A funny thing happened on the way to the mosque, or Two mullahs walked into a bar, but they wouldn’t do that, would they, and if they did nobody would make a joke of it. In the struggle between the clever and the banal the latter is less dangerous. I ask where’s she from.

Los Angeles.

I mean originally. Where were you born?

How about East LA?

No, not really. I heard you answer the one armed man. You don’t speak Spanish.

Lots of those who do think I’m from there.

Coy is not my favorite attitude. Before I can decide how to move the conversation forward, a good looking, dark haired young man, mid twenties or so, approaches, leans over the table, ignores me, and begins to speak directly at Aisha in Farsi, a language whose sound has become familiar to we who live in West Los Angeles ever since the Ayatollah Khomeini’s antics sent hordes of Iranians into exile and so many settled near UCLA that Westwood Boulevard, with its halal restaurants, has been officially named Little Tehran.

Hearing Aisha respond in Farsi makes my heart sink. I know. I know as well as you do: these days we are all supposed to embrace every tradition in the world. I do, believe me, I value every single last one. But let’s face it: we all have preferences in food so why not in cultures? Here’s my confession: were I asked to rank them, I would place Iran somewhere near the bottom, just below Kyrgystan, a country about which I know not a single fact beyond its name. Why Iran? Let me assure you it has nothing to do with those TV images of fists shaking at the Great Satan during the hostage crisis of 1980, though as a supporter of radical movements I was annoyed when religious fanatics hijacked the revolution and pushed out its secular and socialist elements. More off putting is the attitude of Iranian waiters and airport limo drivers (and all limo drivers to LAX are Iranian), who stick their noses skyward as they inform you they were rich business men and engineers back in Tehran, not to mention cousins of the Shah. To this I add the experience of my friend Russell Levine, who invested in a computer parts business owned by an Iranian named Ahmed and soon learned that the chips they were able to wholesale cheaply had been stolen from the warehouses of the manufacturers by distant relatives of his partner. When Russell moved to dissolve the partnership, Ahmed pulled a revolver from his desk drawer, waved it around, then fired three shots into the ceiling.

Nobody dissolves a partnership with Ahmed Sherazi, he yelled. If there is any dissolving to do, Ahmed Sherazi will do it. I spit on your partnership. I spit on your family. I spit on your ancestors. I spit on you.

As the young man’s voice edges from friendly towards harsh, Russell is on my mind. But who knows? Maybe that’s the way Farsi is normally spoken between natives. Aisha sounds less sexy than in English when she attempts to interrupt a couple of times, but the guy doesn’t bother to listen or even slow down. I attempt to change the dynamic by introducing myself, My name is Benjamin, I’m . . . but neither of them takes notice. Okay. Maybe he’s a long lost friend. A distant relative. They haven’t seen each other in years. They’re too excited at this reunion to pay attention to a stranger. Then again, maybe not. His voice grows increasingly unpleasant and Aisha’s responses seem a bit sharper. I touch her arm: Can I help?

She pulls away, stands up, and says something in a tone which has to be Farsi equivalent of Get lost! The guy gestures with his right arm, turns and marches away from the table. Aisha sits down.

I wait a while before saying: Apparently this is your day for encounters with strangers.

She doesn’t answer

He came up as if he knew you.

She shakes her head.

Men from that part of the world! They want to protect their women, that’s the excuse. Their women! My face reminded him of his sisters. That’s one you hear all the time. Oh yes, he wanted to talk about our heritage. I mean he’s British now but he was born in Tehran. When I said I’m not from Iran, he didn’t bother to listen. Islam unites us, that’s what he said. A thousand years ago this was our country, a great Muslim civilization at a time when Europeans huddled in mud huts and lived on roots and berries. It’s time to take it back.

If such words were spoken today, in the first decade of the Twenty First Century, if I heard them, if you heard them, if anybody heard them, what could we think other than terrorist? Sleeper cell. Bombs ready to explode. Clear the subways. Empty the busses. Batten down the hatches. But in 1996 the idea of Muslims attempting to conquer a European country seemed funny enough to make me laugh aloud. Aisha did not look amused.

He said a good Muslim girl shouldn’t be sitting in a café alone with a kafir. He said I’m disgracing Islam. He said I should go off with him.

A kafir? Is that what I am? What’s a kafir?

Someone without a proper religion, you know, like a Hindu or a Buddhist. But you’re Jewish, aren’t you? Yahudi. That’s different from kafir. He got really angry when I said I make my own decisions, and my decision was to sit wherever I want to sit and with anyone I want to sit with and it was none of his business.

You’re not Persian, then? But you guys were speaking Farsi?

Dari, she says sharply. Don’t confuse the two. Ours is the pure language. Nobody’s been a Persian for a thousand years. They’re Iranians no matter how they try to cover it up. No, thank God I’m not Persian. I’m from Afghanistan. She pronounces the word with a guttural gh and long a’s as in ah. Never call us Persians and never ever call us Arabs.

Afghanistan. A pleasant surprise. Afghanistan. The word calls forth images of barren mountains and splendid deserts, ferocious warriors, mujahaddin, groups of dark, handsome men with beards and soft hats, rifles aloft as they ride on the back of open trucks into a blazing sunrise or sunset. Afghanistan means freedom fighters. Holy warriors. Guerrillas who kicked the shit out of the Russian military for a decade and helped to bring down the Soviet Union.

You’re the first Afghan I’ve ever met. Or should I say Afghani?

Wars have been fought over that question. It’s safer to use our ethnic labels. I’m a Pashtun. She pronounces the word as if it contains several o’s.

Pashtun?

Kipling and other British writers call us Pathans. Maybe that sounds more familiar?

No. Not really.

Sorry but I don’t have time to explain about Pashtuns right now. It’s too long a story for one cup of coffee.

I can order another.

I don’t have time.

How about tomorrow?

I’ve working for the next few days.

You’re not a tourist, then? You’re here on business?

I’m here with a film. I’m the producer and director and just about everything else. It’s about my countrymen, the ones who are in America. The title is Far From Afghanistan

Aisha does not have a face I imagine behind a camera but in front of it, her image projected onto the big screen in one of those Bollywood musical extravaganzas. She has the coal dark eyes, the wavy hair, the high bridged nose, the jewelry on the neck, ears, and fingers of those singing and dancing beauties always on the verge of being kissed by a fiancé, but every time his handsome face comes close to hers, she and fifty other girls whirl away into yet another interminable dance number. The lips of the engaged couple never do touch until the final shot, and then with their mouths closed as in Hollywood films of the forties.

Shall I tell her my own reasons for being here? No. Not yet. Always let women do the talking. Makes them think you’re sensitive and understanding. One of those rare males they claim to be seeking. So of course I ask about her film and the festival.

It opened last night, she tells me. At the Filmoteca. The whole festival is devoted to works by women directors, American women, sponsored by the State Department. We’re going to tour Spain for a month with our films and be promoted as wonderful examples of multi cultural America. Eight of us, each from a different background. Only one Anglo in the crowd. It’s a great opportunity, no doubt about it, but honestly this multi cultural stuff gets me down. I’d just as soon be an American without the hyphen, but then I wouldn’t have been invited. My film’s about three Afghan families in the United States, refugees from the Russian invasion. How they struggle in this new and alien world, how they cope with the move from a primitive to a modern country. You can’t imagine the pain of transition, of living a new life, the problems with language, and shopping and getting a job and passing a driving test. Back home anybody can jump in a car and start driving. Nobody cares. Back home when you send the servant to the market for cheese, you know exactly what he’ll come back with. There’s only one kind. Send him for bread and he has two choices. Imagine the first time you walk into a supermarket in America and are confronted with thirty kinds of cheese and who knows how many kinds of bread. You can go crazy trying to make a decision, and that’s only one of many ways the US can drive you out of your mind. Sure, eventually things become familiar but familiarity can mean better or it can mean worse. It depends. But I can’t explain all this in words. That’s why I make films. Come to see mine tomorrow. I’d be interested in your response.

I accept the invitation, then insist on walking Aisha back to her hotel. Where’s she staying? The Reina Victoria. Ah, the famed hotel of bullfighters. Love and death in the afternoon.

They told us that, she says, but I haven’t seen a bullfighter yet. At least I don’t think so. What does a bullfighter look like?

Think Pedro Romero in The Sun Also Rises. Remember the film? Tyrone Power. Ava Gardner. And the young torero, an unknown actor with patent leather hair, a beak for a nose, intense brown eyes, slender as a sapling.

I never saw it, but the film sounds sexy.

Isn’t it pretty to think so.

During our twenty minute walk I desperately dredge from the depths of my memory every fact or rumor I have ever heard about Islamic Spain. Belatedly I bless Dolores for dragging me to Granada a decade ago. That trip allows me to dwell on the beauties of the Alhambra, the honeycomb ceilings of the women’s quarters, the courtyard with its lion fountain, copied from one in the home of a famed Twelfth Century Jewish physician, the lush gardens and reflecting pools of the summer villa, the Generalife. Moving on to a description of Sevilla proves to be more problematic, for I only spent three days there during a conference on the topic, Andalucia, Quiepo de Llano, y la Destina Sevillana Antes y Despues la Geurra Civil. It was held in the main building of the university, which in the eighteenth century housed the cigar factory where the legendary Carmen worked. Pleading off the tours arranged for the visiting scholars, I spent my late afternoons vainly trying to hook up with some of her spiritual descendants. To Aisha I mention the factory, not the girls, then go on to the charming whitewashed houses of the Barrio Santa Cruz and the elegance of the Torre de Plata, the octagonal Silver Tower which looms over the Guadalquivir canal not far from the bull ring.

That pretty much does it. Nine sojourns in Spain, almost two full years in all, and I have never given any sustained thought to the seven centuries of Muslim rule. A sense of shame should make me blush to admit that on two occasions I had driven past Cordoba without bothering to stop and tour the former capital of a rich Islamic country with its world famous mosque (at least I know it’s famous!) dating from the eighth century. That I have never visited it doesn’t for one moment keep from describing the mosque at great length, waxing on about its heavenly architecture (I have looked at plenty of photos), explaining how its thousands of columns and striped arches are meant to recall the palm groves of the Middle East and create a feeling of the infinite.

We’ll be at the Filmoteca in Cordoba next week, Aisha says. I can hardly wait. The masjid there is one of the wonders of our world. So’s the Alhambra, but we’re not showing in Granada. Another place I want to visit is Medina al Zahara. Have you ever been there?

My mind is a huge blank.

I’ve heard the name, I say, but . . . I don’t quite . . .

It’s an ancient city somewhere near Cordoba, full of palaces and gardens. Now it’s mostly ruins, an archeological site, but once it was full of gold and silver and precious jewels and wonderful gardens and fountains. It was built by a Khalifa and named for his favorite mistress. The one he loved until the day she died. Isn’t that romantic? Poets have written about Medina al Zahara for centuries.

We reach the Plaza Santa Ana and stop in front of the hotel. No longer willing to restrain myself, I say that there’s something strange and unusual about meeting you today. At the very least, it’s a wonderful coincidence. For I’m here with a film, too, a very different kind of film, one that’s not really mine but based on a book I wrote. It’s being directed by TJ, I say. His first. You know who TJ is, don’t you?

Her smile is full of mischief.

You must think we Afghans are a very primitive people. Is there anyone in the universe who doesn’t know TJ? Tribesmen living in the remote Hindu Kush think of him as The Most Beautiful Man in the World. That’s what all the magazines say, that’s what’s on TV. But you can tell me firsthand: is it true?

I’m not the right person to ask. These days he wants to be more than just a pretty face. That’s why he’s making the film. It’s about the Americans who fought in the Spanish Civil War. Guys who had a sense of duty, who thought the world was one. They wanted to stop Hitler in his tracks. People don’t remember it much these days, but it was a kind of dress rehearsal for World War Two. The left against the right, democrats and radicals against fascists. I was one of the screen writers.

I want her to ask me about the book. I want her to ask me about the war. I want her to ask me about the screenplay. I want her to ask about commitment, sacrifice, martyrdom. I want her to ask why I wrote about people who volunteer for a foreign war, what’s my interest in those who put their lives on the line for a cause.

Hollywood! says Aisha. All that glamour, excitement, money. It must be wonderful to work on a Hollywood film. What’s the name?

Red Star Over Madrid.

I don’t tell her that I can’t stand the title. A decade later I still can’t stand it even if the film did win me an Oscar. Early on in the endless years of preproduction I asked TJ: Why not use the same title as my book, Crusade in Spain. Don’t be ridiculous, he replied. We’d destroy what little revenue we get out of the Arab world.

The Red Star, asks Aisha. Is that a character? Is that TJ?

You got it. He’s always the star. The film’s about a bunch of Americans who fought for the Spanish Republic. Lots of them were Communists. TJ plays the commander.

We had Communists in Afghanistan. Too many of them. They ran the country for a while and pretty much destroyed it. That’s why we’re scattered all over Europe and the States. I’d love to hear more about your film but I don’t have time. The opening reception is in half an hour.

How about tomorrow? We could get together after your screening.

Let’s wait and see, she says. Who knows what will happen? Inshallah.

The lobby of the hotel is crowded with gilt edged furniture that would fit in a high class Victorian brothel. Photos of Manolete, Dominguin and other legendary toreros of the Thirties and Forties crowd one section of the wall, but don’t bother to go looking for them today. The Reina Victoria was renovated for the new century, and while its clock tower and Victorian facade remain, the lobby is now full of angular leather couches and chrome tables which exude all the warmth of a corporate headquarters, and the wall features photos of recent rock stars whose names I for one don’t know.

We shake hands. When Aisha repeats her invitation, I feel a need to reciprocate. Might she be interested, I wonder, in visiting our company on location? We’re just a forty-five minute ride from Madrid. What I hope is that she’ll answer No, not really. Commercial film doesn’t much interest her. Hollywood is too vulgar, too empty, too formulaic for her taste. She prefers independent films, works of cinematic art that stretch the eye and the mind. She likes writers who used to be historians.

Wonderful, she says. That would be such a treat. Thanks so much. I’ve been working with film for over a decade and have never seen a real feature in production. Would I get to meet TJ? It would be such a thrill for my Mom and my sisters and all my relatives and friends.

A twinge tugs my heart. TJ’s fame, as everyone in the world must know, stems less from any acting talent than from his remarkably good looks and much publicized ability to get women—young, old, famous, beautiful, infamous it doesn’t much matter—into his bed and onto the front page of the National Inquirer. In theory his mating habits should be of no concern to me. I have just finished going through a divorce prolonged for more than two years by a struggle over what little property we owned, and my attorney has warned me that when it comes to women I should keep a low profile. In California a property settlement is never really settled, he explained, and your ex seems so trigger happy she might well try to reopen things up if she learns you’re involved with someone. So keep your zipper closed until she’s hooked up with another guy.

Sage advice, I’m certain, and after two marriages wholly consonant with my current feeling about getting involved with women. That’s no doubt why it has been easy for me to swear off of them for the duration. Problem is, meeting Aisha makes it seem as if the duration is up.