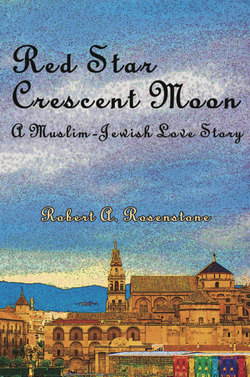

Читать книгу Red Star, Crescent Moon: A Muslim-Jewish Love Story - Robert A. Rosenstone - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 Aisha

ОглавлениеYou can’t imagine what a pleasure it was to be in Spain, a country where I didn’t have to worry about my name, where I didn’t have to pretend and hide or get annoyed or angry at all the stupid questions Americans are always asking. Where are you from, with a big smile, as if it’s their business. People you meet on the street or in a supermarket or the new teller in the bank or hiking on a trail in the hills or even in an editing room or on location and even if you’re the one in charge, everyone has the right to ask just because they are a blonde: where are you from? And if you answer Los Angeles they laugh or look at you funny and shake their heads and say No where are you really from, where are you originally from, where were you born, where did you grow up, where did your grandparents live, and their grandparents, and all I am hearing is What are you a brown person doing here when you should be somewhere else maybe in a jungle or a desert or on a bare mountain top because this is a country where only blondes belong, even if they aren’t blonde, even if they are Chinese or Jewish and darker than me. It’s no better with Latinos. They come up thinking I am one of them and speaking to me as if I am a sister, asking questions or saying something habla this and habla that, and I answer in perfect English, well, almost perfect, I’m sorry I don’t speak Spanish, and they look at me as if I am betraying our mutual heritage, pretending to be Anglo when I am really one of them, and it doesn’t help one bit if I answer in Dari or Arabic or Urdu, they just turn away babbling in Spanish. I am studying the language now and it’s a nice language that I like very much, it’s sweet and musical. But not in Madrid. Here the hotel clerks spit words at you as if they are firing machine guns. It makes you wonder about the reputation of Spanish lovers, Don Juans, but that’s probably another cliche in a world full of cliches. You certainly wouldn’t want someone to sound that way in bed, but that’s something I will never get to find out.

The afternoon I meet Benjamin in the Plaza Mayor is my first time alone since arriving in Madrid the day before and being given a kind of royal treatment that one does not expect as the director of a documentary, but I was far too jagged and lagged and sleepy from the flight to appreciate it. A middle-aged woman named Immaculada who speaks English and seems to be a sort of a hostess and chaperone combined meets me at the airport by holding up a sign, Aisha Sultani, and after a warm greeting and kisses on both cheeks she takes me in her car to the Hotel Reina Victoria where I go directly to bed and sleep sixteen straight hours. Early the next day Immaculada woke me early and took me off to the screening of a film, something about lesbians and bisexuals with psychological issues, and my reaction is something like God you sometimes wonder what these Westerners these Europeans these American women are thinking with all their closeups of piercing and cutting and vomit. Don’t they have anything else to make films about? I’ll never understand. They’re too rich and spoiled and what do they know about life? They haven’t been invaded, they haven’t been bombed, they haven’t had their uncles pulled out of a car and shot at a roadblock, they haven’t had mullahs telling them they had to hide their faces, they haven’t had brothers disappear one night, never to return, they haven’t seen the flares go up over the city or the terrifying but beautiful tracer bullets fired from rooftop to rooftop or huddled in a basement waiting for the artillery explosions to stop. And they haven’t had lovers either, not real lovers, haven’t had sweet words whispered over a phone line in the middle of the night when everyone else is asleep, haven’t strolled with girlfriends across the schoolyard and seen Him sitting in his father’s car across the street, looking so proud and handsome waiting there just to see you and that feeling flies back and forth in the air, that love in his eyes meeting the love in your eyes, even though you have never been alone together, only have seen each other up close at huge holiday gatherings with all the cousins, and yet you know, both of you know that this is True Love.

Sometimes I have to wonder why we always so much admired the West. Europe. England. America. Where everything was modern and clean and up to date, like the Siemens fixtures in our bathroom and appliances in our kitchen in Kabul. In the West things worked and everyone was rich. No goats herded through the streets, no heaps of animal or human dung, no ragged peasants, no blind men with their hands out for baksheesh, no two wheeled carts pulled by boys, no carcasses of sheep and cows hanging in front of butcher shops, covered with flies and dripping blood into the dust, no run down stores with shop keepers sitting over tiny coal heaters, cooking soup, looking up and calling Come into my store and you’ll get the best deal. Sometimes Kabul seemed horrible. I always wondered when we came back from a period abroad why my country was so poor, so dirty, so primitive. Why couldn’t we be like the rest of the world, if not Europe than at least Turkey or Egypt.

Twenty years in America and I have begun to learn, begun to see the two worlds, Sharq and Gharb, East and West, as centuries apart. Yet the violence these young filmmakers show is fake because they don’t know the real thing, don’t have a clue. Violence is what they give you instead of love and they don’t have a clue about that either. Women who don’t accept the fact that men are different from us. Women who complain about men as if men were supposed to feel and act as we do. Women who have not for the life of me ever felt a tenth of what we feel with that single wave across the schoolyard or a few words whispered in a hallway during a feast like Eid el fitr which marks the end of Ramadan.

One of the wonderful things in Madrid is that so far nobody has asked me where I am from. They think I am an American, that’s it, even if a lot of them have to know because my background has been mentioned in all the publicity—our first Afghan American director!! and almost always with the exclamation points. I am here because I have put my community on the screen and so I represent multi cultural America, where everyone always asks you where you are from. But here nobody asks not even those who don’t know. Maybe they simply aren’t curious or maybe they look at my face and think the Moors are back, better not mess with her or they’ll be another invasion. That much Spanish I could understand: No que es su pais natal, senorita. It’s an easy language, a lot easier to learn than Arabic and a lot easier than English, which I learned so long ago. My father was smart. He knew even back then that English was the language of the future and so while he and mother stayed in New Delhi, they bundled us off to school in Missoura, an old British hill station, where the Nuns made us say Hail Marys before I cried myself to sleep. It was so cold, the Nuns didn’t believe in heating, it made you soft they said, and that’s why we had all those cold baths in the morning which were supposed to be good for you. The best part was on Saturdays when all of us in the school, marched two by two, holding hands, sandwiches and fruit in our brown bags, down the hill to the movie house to see cowboys and Indians or the real Indians from India, some jumped up version of the ones around us in the streets, only on screen they were dancing and singing, the women rolling their eyes like huge billiard balls and skipping across fields, almost but never quite kissing their handsome boy friends for just as their lips draw near and they look deep into each other’s eyes another song begins and away they whirl in yet another dance, dozens of women in bright saris in vivid green fields or boulder strewn mountains or in the courtyards of marble palaces.

The festival has put us in a wonderful and elegant hotel, with huge bay windows looking out on a green plaza across the street, and textured, flowery wallpaper, and thick carpets in the hall that caress your feet. Today I am free in the afternoon for what they call siesta, only after sixteen hours of sleep I am plenty rested and I want to make good use of my time in Madrid. Maybe I shouldn’t be wearing such thin soled sandals, but it’s gloriously warm this afternoon and my feet are the only place I dare feel naked, covered up as I am like a boy, with dark, silky pants and a long sleeved blouse, my hair up with a scarf around my neck not over my head. I don’t want to carry the stereotype too far but I will need the scarf if I go into a church, that’s one time where Catholicism and Islam aren’t so far apart. The dark, handsome bellboy with the gleaming black hair touches his cap in a salute as I walk toward the elevator. All the bellboys are dark and handsome. They look like bullfighters are supposed to look, their movements graceful and proud when they pick up a suitcase or unlock the door of your room and bow you inside, their eyes smoldering, glances full of a kind of contained passion that seems to suggest I would like to take you in my arms and call you mi amor.

Mmm, this country is great for the fantasy life. In the lobby, with the brocade and velvet sofas and chairs, and gleaming candle holders and glittering chandeliers, and Persian rugs, you can think you may have just walked into some palace out of the past. The women, are they guests or maybe hookers off duty, wear stark colors, white, black, or red, with lace shawls, their necks curved and mobile like swans, their hair piled all the way to heaven, the earrings swinging like huge pendants, and the way they stand, at once dignified and disdainful, slightly curved bodies in a maddening pose that has to be a threat and a challenge that if I were a man I would answer with violence, would be all over them in a moment, dragging them off to a bedroom and tying them to the posts of the bed. The men are sexy too, in dark suits and gleaming shirts, erect, centered, quiet, watching from beneath lowered eyelids, like that one at the desk who has just flicked his eyes my way for the tiniest of seconds, cool, a bullfighter surely for they say this is the hotel where bullfighters stay.

Do we ever escape our tradition? Our past? Or do we just drag it around like a huge suitcase on wheels, getting larger and heavier every year and more difficult to pull? I cross the street into a charming square named Plaza Santa Ana. So many names are a mystery here but at least Reina Victoria is familiar to me from the British nuns who never tired of telling us their convent was founded under Queen Victoria. There are stone and iron benches under leafy trees full of older people, and the beggar sitting on the ground, hair grizzled and white, his cap before him, looks up with an expression that takes me right back to Kabul to the one who used to sit on the same corner of our street in Sharinaw every day and look up as we walked by him on the way to school and his eyes stuck a needle into my heart, they were so sad, so full of pain mixed with faith, or a desperate hope, waiting for a reward in Jinat but now resigned to sitting in the dirt, to the laughs of young girls like my sisters, hurrying along, happy without knowing it because they are clean and well fed and dressed and I am the one to stop, stare into those eyes which silently teach me about my own mortality, and I hand over the pocket money I was going to use for sweets at the Indian spice shop, and then hurry down the street. We never once spoke, the beggar and I, though he was there for a year or more, and then one day he was gone, and that night I prayed that his soul was in Jinat, with the arms of the grape trees bending toward his mouth, the maidens holding him, rocking him to sleep at night, telling him that life had only been a bad dream and now at last he was really awake.

The question for me in Madrid was Am I awake? Is this really me, alone in a foreign city with no man to tell me what to do, no brother and no husband and no uncle and no strange man who insists on calling me sister, can I help you sister. I am free for a change, free abroad for the first time in my life without anyone to make demands. It’s nice to be alone with no sisters at my elbow, jabbering about relatives or borrowing money or trying to drag me to yet another mall to find just the perfect bargain in leather pants or jade earrings. Do they have malls here? I haven’t seen any yet, but maybe they’re in the suburbs if they have suburbs here. I know nothing about this city, nothing about this country, nothing about these buildings, with their ornate facades. I wonder what they call this architecture. I wonder what history these buildings contain. We never studied architecture and we never studied our own history very much and certainly not the history of Europe. Only Alexander the Great, how we were the only ones to defeat him, and the only ones to defeat the British and we did that twice. Aren’t we wonderful, we defeat everyone including ourselves, but nobody talks about that. Our history. I hated that long list of dates of battles and of emirs and shahs and poets and holy men, Timur and Ghengis Khan and Dost Mohammed and Rumi, but nothing about who they really were or how treated their wives and daughters.

The directions from the desk clerk are clear. I am to walk down this street named Calle de las Huertas, meaning what? I pass tiny restaurants and plenty of small stores, boutiques, with jewelry, scarves, jackets, shawls, and shoes, wonderful shoes but not shoes you could walk in, not with those heels, not on these cobblestones. It’s wonderful to walk where you want and have no men sidle up to grab your arm or push against your breast or call you a bad name for being alone. The men on the street don’t all look like actors as did those in the hotel, but I like their discretion, the way they look at me, see me, but not with a stare, more of a glance, a slight smile, of appreciation perhaps? I look good today. I know I look good when I am not working and harassed. They are wondering: is she one of us or a foreigner? The people are mixed here, you can see the combinations clearly in the body types, the skin tone, the hair color, the slightly beaked noses, the full lips that whisper of North Africa. A few are blondes but not real blondes. The kind of blondes you get in any dark country where hair coloring and peroxide drip to the roots.

I reach the archway the clerk mentioned and go through the shade of a tunnel and out into the sunlight of a huge square. The Plaza Mayor. What an amazing space! Enormous buildings with arcades and balconies and on one of them, huge paintings of nude women climbing and twisting up the facade. It’s like a stage setting for a great pageant. I see women in long, full dresses, holding silk parasols in one arm while the other is entwined with that of a man in a frock coat and top hat who carries a walking stick. You expect carriages with drivers and lackeys in uniform, the hooves of horses clattering over the cobblestones, while on those balconies women with enormous piles of hair and diamond necklaces drink champagne from crystal flutes and smile down on their inferiors. Right now the plaza seems both empty and full of life, café tables with bright awnings spill out of arcades, waiters in black jackets and white aprons hurry along with trays of food and drinks, guitarists, bongo drummers, and violinists play furiously with their instrument cases open on the ground to catch coins, painters at easels sketch portraits of bulky tourists, groups of furtive men in tweed jackets and hats, in this weather? cluster in a corner of a far arcade, arguing heatedly, buying, selling something small, very small—but what? coins? stamps? drugs?

I avoid the cafes for a stone bench not far from a bronze statue of a man on a rearing horse. Women alone in outdoor cafes are prostitutes, aren’t they; or taken for prostitutes. It’s the same thing. If I sit here I won’t have to deal with waiters or other foreigners like me, Americans or Brits who will no doubt ask where I am from. It’s a circular bench, a ledge really, around a tall iron street lamp. The sun is just sinking behind the buildings that line the square. I sit down next to two mothers with squalling babies in strollers. On my other side a very old one armed man who badly needs a shave and wears a summer jacket with the sleeve neatly pinned to the shoulder lights a match by flicking it with his thumb, then touches it to the cigarette in his lips, one of those foul smelling smokes that might as well be a cigar. Beyond the women is a figure I glimpse when sitting down. Benjamin. This is our famous meeting, but at the time all I know is that it’s someone who is very aware of me and wants me to be aware of him, only I want to be alone so I can enjoy the buildings and the space and the doings of Plaza Mayor without having to think or talk or be social.

One thing in life is certain: you are never alone for long. A slender young man with long, messy blonde hair approaches and asks do I speak English. He has a slight accent that I don’t recognize. I say yes and he stands in front of me with his head tilted slightly to the right as if there is something wrong with his neck, and his arms hang by his side, and his fingers twitch, and he begins a story about what sad and difficult things have happened to him here in Spain in the last few days. He is Dutch, and this was his last big vacation before going to work, he has wanted to come to Spain all his life. He starts a job next week, back home, in computers, software, but three days ago his backpack was stolen in a youth hostel, and his wallet was in the backpack, but the people running the hostel wouldn’t believe him and threw him out, and when he went to the cops they shrugged and said you Dutch are rich, just get some money from home, but his parents are on vacation in Italy and he can’t reach them, and his friends are all away on vacation too. It’s just a matter of two or three days. He keeps making collect calls and soon his parents will be home and wire him the money, but right now he’s starving, and he has been sleeping in the corner of the square for three days, trying to keep clean washing at the public fountains but that’s illegal and cops threatened to arrest him if he tries washing there again.

The two mothers stand up and push off with their strollers, the one armed man keeps smoking, uninterested in the babble of foreigners, and the man on the right begins to edge closer to me on the bench. I ignore the impulse to look his way, yet I can’t fail to hear his voice, a warm voice, say something about how the youngster wants to take advantage of me. I do remember the line: If his story is true, I’m the king of Spain. What nerve from a stranger on a bench, as if I don’t know my way around the world, as if I haven’t lived in fifteen different countries, some of them like Egypt and India where the beggars have their hands out everywhere you go. I pride myself on knowing when one of them is telling the truth.

The young man hears these words too and responds not with anger, which is what you would expect if his story weren’t true. You’re right, he says, and if I were you, I’d be suspicious too. You’ve never seen me before. I must look like a bum or a drug addict. It would be natural to think I’m going to take money and buy drugs and stick a needle in my arm. But look at my arm, and he rolls up his right sleeve and then his left. You can see there’s no needle marks. My family we are good middle class people and I’m a graduate of the University of Amsterdam in mathematics. I didn’t know this kind of thing could happen in Europe today. Give me your address. I swear I’ll pay you back. I have my pride. I hate the idea of asking strangers for something, but lady, your face is so kind that it gave me the courage to come up to you. I thought here is someone who will believe me. Honest. I swear on the Bible this is true.

Somewhere in the middle of this, his voice cracks with emotion and a tear trickles from his right eye. I fumble with my purse, pull out my wallet, which contains more dollars than pesetas. How much should I give him? Ten dollars? That doesn’t seem enough. Twenty? For all the honor of being at the festival, this trip is costing me out of pocket and I’m not exactly rolling in money.

The voice on my right speaks again, saying that if I’m going to give a donation to the cause that I should keep the amount small. I have never liked taking orders, so I hand over a twenty dollar bill, and while the boy is blubbering thank you, I turn towards the voice. The face doesn’t go with it. Not at all. I don’t expect such a substantial nose or such penetrating blue eyes. I don’t expect a face that has to be Jewish because the voice is so not quite American but different, somehow, yet not British either and certainly not full of the nasal tones that seem characteristic of so many of the Jews that I have met in America, and once you are in Los Angeles it seems that just about everyone you meet is Jewish.

You have made a mistake, the voice tells me, and I respond, politely as I can when I feel annoyed, that it’s none of his business, that the poor child looked so hungry and desperate, and when the voice agrees the young man is certainly both of those, the tone is slightly mocking and yet full of an invitation, and the question becomes whether I want to respond. Sound is important to me, often more important that what is being said, and despite the annoyance I like the sound of this voice, warm, soothing like an announcer on a classical music station, and yet with a certain sense of command. Okay, I’m not always the good girl that I seem to be. I have my own way of being provocative, so I respond that we call it baksheesh and we think it’s a duty for Muslims to help those who can’t help themselves. He takes that as an opening and introduces himself as Benjamin Redstone. What kind of a name is that for a Jew?

Alison, I say, trying out my new name for the first time. I’ve been thinking about this change long before arriving here. Say Aisha and people never get it. Not Americans and somehow Europeans are even worse. Asia? Asthma? Ashes? Ashi? They always look slightly puzzled, even more so if I explain, as I used to when I first arrived in Kansas, that it’s a historic name, a holy name, the name of the youngest and most favored wife of the Prophet, may peace be upon him. His fourteenth wife. His fourteenth wife? That was the usual reaction. He had fourteen wives? And then begin the smirks suggesting You guys are weirder than we thought, followed by the heavy handed jokes, which are even worse.

Alison? He says the word as if he doesn’t believe its my real name, as if he knows such a name does not go with this skin and these eyes and this hair. He asks if this is my first time in Madrid.

There are some people whose intonations and expressions, whose posture and body movement, whose very aura, which you can’t see but feel even if you can never put that feeling into images or words, people whose very presence gives you sense of comfort, a feeling of the familiar, as if you know them already, have met them before, shared secrets with them in another time and place or perhaps another life if you can believe all that stuff the Hindus believe, and even if you can’t believe it, and I certainly don’t, it doesn’t banish the truth that there are people who immediately put you at ease, make you trust them enough to say things you haven’t said to others unless you have known them for decades and maybe not even then. That sudden feeling, those certain people are among the many mysteries which only Khodajan can understand. How else could you explain that Benjamin is one of them?

Yes, I answer. It is my first time in Spain, first time in Europe other than a few hours at Charles De Gaulle airport though I don’t say that was years and years ago on my way to America, and for the first time but not the last, there will never be a last, will there? he gets clever and historical with me, and asks, But is Spain really Europe? When I don’t have an answer he explains that a French king once said that Europe ends at the Pyrenees and that Spain is different from everywhere else on the continent because of the legacy of Islam, seven hundred years as a Muslim society when Europeans were the foreigners here.

My response surprises me: I know all about that. I’m a Muslim. I will always be a Muslim.

What a thing to say! Am I afraid he is going to try to convert me, put on one of those little hats and start babbling things in Hebrew that will steal away my soul? Do Jews try to convert people? If they do they must get extra credit for a Muslim. I do know that Jews are clever and smart and always trying to trick Muslims. That’s what my grandmother said. Everyone says it. With Jews you have to be careful or they’ll steal the socks from inside the shoes on your feet.

I don’t remember his response, but I startle myself a second time by saying that I’m an Afghan. An Afghan? Since when did I begin to volunteer where I’m from to perfect strangers. When people ask I usually dodge the question or refuse to answer or make them guess, Where do you think I’m from? The responses are all over the map—Turkey, India, Iran, Lebanon, sometimes a Latin country, Mexico, Colombia, Brazil. No one ever says Afghanistan. Even before the war and the American invasion and Al Quaeda and all that, when they heard the name of my homeland their reactions were strange. Some would go sort of blank and not know what to say, as if I had just revealed that I was from Mars. Others would go on and on about women in veils as if veils were the central part of my existence, and they always seemed to resent it when I explained that I never wore one. When I first got to Kansas, the response was always Oh, you’re from Africa, that’s cool. During the Soviet period it became a badge of honor, even in wintry Lawrence, to know about the landscape and people of my homeland. At parties I was always drowned in shouts about your glorious Freedom Fighters. Great people, your people, giving hell to the Russians, way to go. Whenever I tried to explain that the translation for mujahaddin was not Freedom Fighter but Holy Warrior, they would back off, saying No reason a Freedom Fighter can’t be a Holy Warrior too. Nothing wrong with fighting for your faith.

America seems to love freedom fighters, even those who haven’t the slightest idea what freedom might be.

Benjamin’s reaction to the word, Afghanistan, is not at all what I expect though I can’t be certain what I did expect. He says that being Afghan sounds a lot like being Jewish. What an idea! Nothing could be farther from the truth, or so I think, even while he goes on about both groups never being taken for granted, but I am listening less to the meaning of his words and more to the sound of his voice. I have the impulse to ask why he isn’t wearing one of those little skull caps, but I restrain myself because who knows? it may be impolite, you never know with people’s beliefs, and to tell the truth, I am enjoying this back and forth, it’s a me I like, a freer than usual me, talking with a man who is, let’s face it, picking me up, if I wish to be honest about what is happening, and if mother told me one thing a million times it was that I should not talk to strange men for you never know what will happen but you do know that there is only one thing that they really want.

We have broken some sort of ice. We both know that as we sit in a warm silence, watching the sun disappear behind the buildings on the far side of the Plaza, the shadows stretching out to engulf a column of elderly Asian women carrying parasols, marching behind two young female guides in bright red suits, one of them holding a small triangular flag on a slender pole. They make for the bronze statue of the man on the rearing horse, stop in front of it, sort themselves it into three neat lines, as if they have been practicing this maneuver all their lives, shorter women in front, taller ones in the middle, tallest ones in back. The guides shoot photos, and then each woman in turn steps out of the group, points a camera at her comrades and a flash stabs through the dusk. After every one has taken a turn, they reform into a column and march towards a distant archway and out of the plaza.

Benjamin begins a lecture about the king on the horse, a Felipe with some number after his name who had this plaza built in the seventeenth or eighteenth century, and while I begin to wonder if he is going to ask me for a drink and I am going to accept, he goes on about the events they used to have here, horse races and bullfights and public executions and even something about Muslims and Jews being hung or burned, and I keep thinking why is he putting Muslims and Jews together when they are so far apart. Of course I wonder how come he knows so much and all kinds of odd thoughts go through my mind, like what if he is something strange like an FBI agent or a expert in guided missiles or some kind of sneak gas bombs or even maybe a rabbi. His nose sure looks like the nose of a rabbi, but I don’t know if there is there more than one kind of rabbi or are they just like mullahs, sort of the same except some are a lot smarter and better educated and a lot cleaner than others? That’s one of the things that’s wonderful about Islam, you have to be clean and there’s always the fountain in the courtyard of the mosque, a beautiful fountain with that lovely splash of water and you have to wash before praying to Khodajan, no dirty hands or feet or dirty anything when you pray. No he can’t be a rabbi, a rabbi wouldn’t go on talking to a Muslim woman, would he?

It seems like forever before he finally gets around to asking me for a drink. I say no, I don’t have time, because I don’t want to seem easy, but when he asks again I say okay, but only for a minute. This is Europe after all. That’s what you do in Europe, sit in cafes and talk about the kind of stuff Europeans talk about, men and women together, discussing art and literature and politics and sex, no doubt, they are big on talking about sex at least to judge from their movies, French films and even more Spanish films, for what does Almadovar ever have his characters talk about or do for that matter but sex. It’s not like back home, funny I still think of it as home after twenty years, like all over that part of the world where the men sit in coffee houses all day long, smoking from water pipes or cigarettes, Marlboros if they can get them, and if a woman walks in all eyes turn your way and all conversation stops, even the movement on the checker board halts, as if the presence of a woman would jinx the game, and if you are in a Western dress or heaven forbid, jeans, if you are in anything but a huge chadour or a burka, you will feel the eyes undressing you and unless you are seventy five you may as well turn around and walk right back out the door because nobody will serve you a coffee, not even a glass of water if you were dying of thirst.

I am conscious of Benjamin’s physical presence as we move across the square towards one of the outdoor cafes, taller than me but not tall, bulkier but not really bulky, a comfortable size, not like so many Americans, not like the guys in Kansas who were huge as elephants. That’s the way it seemed when we arrived and it was the same when I left four years later, only by then their size made sense for it went along with the baked potatoes that were big as soccer balls and the steaks that looked as if someone had hurled half a cow onto your plate. My introduction to America, straight from the bomb shelters of Beirut, where everything was closed in and dark, and people scurried furtively between buildings during lulls in the fighting, and then you are on a plane, evacuated to Kansas, where the horizon goes on forever, corn fields stretch to the end of the earth and maybe to the stars, and the men, the overgrown boys with bellies already beginning to hang over their wide belts, want to talk about nothing but beer and the size of their farms, or if they are pretending to be Hippies, the secret places they grow dope, and everyone talks about whether the Jayhawks can beat the Sooners this year.

He orders coffee for both of us, and something called churros, which are like thick bread sticks but made with soft donut dough, powdered with sugar, and very sweet on the tongue even if these are, or so he says, rather stale because you really have to eat them at breakfast, and best of all is to buy them from an outdoor vendor in a historic town like Granada, a vendor who cooks them while you wait, for the tastiest ones come from gypsies who carry on the heritage of the Moors. Sitting here in the twilight, couples at nearby tables touching hands, leaning heads close together, kissing on the cheek or lips, I look at him for the first time, see this man whose voice already speaks directly to something in me that I could confuse with my heart, his light summer jacket wrinkled, the white shirt without a collar showing off an elegant neck, not a young neck, to be sure, but one lined and beginning to go a touch scrawny with age. He must be close to fifty, twelve, fifteen years older than me, not young, not old, ripe maybe, old enough, but for what.

It’s not just the sound of the voice but what he is saying. Benjamin has confessed to being a history professor and he is doing what all men do, trying to entertain his female companion, not by talking about himself as they usually do but about history, my least favorite subject at school, though I don’t say that, it would be so impolite, and anyway it sounds interesting now, his words not about dates and kings and battles but about poetry, science, and medicine, gardens and fountains and palaces, the landscape of a bountiful land of milk and honey, and all due to Islam, the fanatic Berbers from the Atlas mountains who led by Arabs stormed across the Straits of Gibralter and stayed here for seven hundred years and left a legacy in music and architecture. He wants to impress me, that’s clear enough, with all these words about what is my heritage not his, though he keeps inserting Jews into the culture, but I don’t mind at all because it’s so rare to find an American who knows anything about Islam or my part of the world though twenty years in America makes it seem less like mine and more like something half remembered from a movie I saw a long time ago.

The interruption by the young Irani ruins my mood. Even here they can’t leave you alone, they close in on you and make demands as if you really were their sister. He starts out nice enough speaking Farsi with an accent that shows he has lived in Britain for most of his life, though I do find it a bit unnerving that he asks if I aren’t the Afghan director who has a film in the festival at the Filmoteca, but I fall into the oldest of my roles or should I say our roles, letting him intrude and forgetting about Benjamin and disappearing into fantasies about Islam and our world, weren’t we the greatest then but not mentioning a thing about the sorry state we are in now. It’s impossible to get over one’s upbringing, impossible to get over your training to always be the good girl and do the right thing even if in everyone’s eyes including my own I am at this moment the farthest thing from a good girl. Maybe that part of the world is still more with me than I know, for after all these years I still listen when a man starts to talk even if I don’t know him and know he is not really my brother and even if he is talking nonsense. Only when he gets nasty about my film, saying he’s heard it slanders my people, do I begin to feel annoyed and only when he asks why am I sitting with a kafir, how can I shame Islam by being with one of them, and only when he demands that I leave immediately, come with him, only then do I wake up to my current self and say It’s none of your business what I do and when he begins to insist Sister, think of our people, that’s when I tell him where to get off and go and he does, though not without the usual threats and curses on my family, past, present, and future.

This encounter changes the feeling between Benjamin and I, though we do get around to my film and the festival and he seems interested in both. I let him walk me back to the hotel and just before we part he surprises me by explaining that he too is in Spain because of a film, not exactly his film, or only partly his, for it’s based on a book he wrote about some Americans who fought in a Spanish Civil War. Imagine that! Americans seem to fight everywhere but in America. It’s a big Hollywood production and the most exciting thing is that the director is that heart throb TJ, whose image is drooled over not just by my sisters and cousins but by most of the women in the world. I have already invited Benjamin to the screening of Far From Afghanistan the next night, and as we approach the hotel my mind is already on the evening’s reception and what I will wear. Outside the door he comes close to me, and I fear that he may try to kiss me, the way sophisticated Americans and Europeans always do, but instead he shakes my hand and says he’ll see me at the screening. Inshallah, I say. Suerte, he replies, then adds that it means Good Luck. I have two hours to get ready to look better than my best. My smashing black dress, jewels in my hair, a native lapis necklace, gold bracelets, and a French scarf passing for a chadour draped around my shoulders. It’s important to do the whole bit. I know that already. The image of the director these days is as important as the images she creates on the screen. Maybe more.