Читать книгу Peripheral Desires - Robert Deam Tobin - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

The Greek Model and Its Masculinist Appropriation

The very title of his book, Eros: The Male Love of the Greeks, underscores the importance of the classical Greek legacy for Heinrich Hössli’s efforts to explain and justify male-male desire. In the first part of the nineteenth century, allusions to ancient Greece not only proved the transhistorical and intercultural nature of same-sex desire, but also vouched for its legitimacy and even nobility. As the century progressed, however, those who thought critically about same-sex desire came to believe that the Greek model provided little evidence in support of the case that homosexuality was an innate, immutable condition affecting only a discrete minority of individuals in need of legal and social protection. In addition, the Greek model seemed to imply intergenerational sex, rather than long-term relationships between adults. By the end of the nineteenth century, therefore, many physicians and activists had hollowed out the Greek model. They continued to refer to prominent figures such as Sappho and Socrates as famous “homosexuals” in order to argue for the eternal nature of that category of sexual desire, as well as to cash in on some of the prestige of antiquity, but they rarely predicated their discussions of same-sex desire on analyses of Greek texts. Instead the Greek tradition came to be honored by a subgroup of peculiarly German nationalist sexual radicals known as “masculinists” who harbored antiliberal, antibourgeois, antimodernist tendencies and who were disproportionately influential among literary writers from Sigmund Freud to Thomas Mann and Franz Kafka.

Nietzsche and His Disciples

While Greece in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries had stood for the Enlightenment and rational, liberal, humanist views, by the end of the nineteenth century the German vision of Greek culture came to be tragic, illiberal, imperial, and pessimistic. No one did more to engineer this change than Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), whose darker view of Greece suited many aspects of Wilhelmine Germany. Under Nietzsche’s tutelage, Greek culture came to be seen as the remedy for the soulless, bourgeois, prosaic liberalism that, according to many conservatives, endangered central European culture. Because Greece was also still known for its representations of same-sex desire, this new vision of antiquity afforded a space for antibourgeois models to compete with the emergent liberal and progressive view of homosexuality found in Ulrichs, Kertbeny, and Westphal. At the close of the nineteenth century, these antiliberal masculinist thinkers echoed a variety of Nietzsche’s arguments about antiquity—including his antifeminist and anti-Enlightenment stances—as they contemplated the role of same-sex desire in Germanic culture.

As Andrew Hewitt observes, “the Greek state offers itself to rightwing ideologues as an alternative to ‘Jewish,’ ‘liberal’ democracy.”1 The question of anti-Semitism in Grecophilic, post-Nietzschean thinking is significant enough that it will be addressed separately in the next chapter. For now, let us focus on the shift in the meaning of Greece from its standing at the beginning of the nineteenth century as a guarantor of human rights, including the rights of men who loved men, to its mobilization at the end of the nineteenth century as part of a critique of liberalism. In the realm of sexuality, this late nineteenth-century version of the Greek model became shorthand for a rejection of liberal models of sexual identity.

Nietzsche’s influence on the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century homosexual emancipation movement in general is surprisingly strong. The writings of the masculinists in particular are laced with discussions of the Übermensch, the priestly spirit, the ascetic ideology, and the herd. In her summary of the authors cited by contributors to Hirschfeld’s Jahrbuch and Brand’s Der Eigene, Marita Keilson-Lauritz finds that Nietzsche is without question the most frequently cited author in Der Eigene, the mouthpiece of the German masculinist homosexual movement.2 Der Eigene often cites epigraphs from Nietzsche and originally sported the subtitle, “Ein Blatt für Alle und Keinen” (A Paper for Everyone and No One), which was a direct allusion to the subtitle of Nietzsche’s Also sprach Zarathustra: Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen (Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for Everyone and No One).

The Nietzschean homosexual is humorously parodied in Otto Julius Bierbaum’s novel Prinz Kuckuck (Prince Cuckoo), which appeared in 1906 and 1907. Although Bierbaum (1865–1910) has remained on the fringes of the canon, Prinz Kuckuck merits attention, because it has one of the earliest German literary representations of a character clearly labeled a homosexual in the modern, sexological sense. Bierbaum’s writings take from Nietzsche a glorification of a pagan, heathen sensual life and are filled with anti-Semitic passages. The novel does not necessarily endorse this philosophy: its anti-Semitic protagonist, Henry, who doesn’t realize his mother is Jewish, comes off as an antihero. In fact, the Nietzschean legacy comes in for particular ridicule in the character of Henry’s adoptive cousin Karl, who in the course of the novel discovers his sexual orientation toward men and becomes a member of a community of homosexual men in London who meet at a private club called the Green Carnation. (Interestingly, Robert Hichens, pseudonym for Robert Smythe, satirized Oscar Wilde in a novel called The Green Carnation, published in 1894; in his introduction to the novel, Stanley Weintraub provides a good history of the meaning of the flower in the world of Wilde and his followers.3) When Karl publishes a book of poetry, a reviewer calls him a “disciple of Nietzsche.”4 Mocking Karl’s understanding of Nietzsche, the narrator does not deny the philosopher’s popularity in the homosexual milieu: “Like most in his generation, he did not actually know Nietzsche and had first heard his name at the Green Carnation, without seeing himself obliged even to read the writings of this man.”5 Bierbaum’s narrator points out that such reputations become self-fulfilling prophecies, as Karl does begin to study Nietzsche himself: “Now, however, he sent for Nietzsche’s books and began to read in them in his way.”6 Bierbaum’s account of the fin-de-siècle Nietzschean homosexual suggests that the figure was recognizable enough to merit caricature.

Caricatured or not, many of the Nietzschean masculinists were intriguing personalities. Elisar von Kupffer, who sometimes went by Elisarion, lived from 1872 to 1942. Born to a Baltic German family in Estonia, he studied in Munich and Berlin, where he met his life partner, Eduard von Mayer (1873–1960), and put together his anthology of poetry from throughout the world dedicated to male-male love, Lieblingminne und Freundesliebe in der Weltliteratur (Ardor for Favorites and Love of Friends in World Literature), which appeared in 1900. Initially confiscated, the book was released for sale after experts, including renowned classicist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (1848–1931), reassured the censors that it had scholarly value. After 1900, Kupffer and Mayer moved to Italy and eventually settled in Minusio, near Ascona, the artists’ colony in Italian-speaking Switzerland, where vegetarians, socialists, nudists, anarchists, and aficionados of modern dance gathered to celebrate life and ponder its reform. Kupffer established a “Sanctuarium arte Elisarion,” a temple devoted to the beauty of male youth, which he filled with his own paintings.7 Although he remained in self-imposed exile in Ascona, he watched the rise of Hitler with interest and even wrote the Führer a letter trying to get him to support the establishment of another temple devoted to male beauty in the new Reich. There was apparently no response. Almost completely forgotten now, Kupffer was the most frequently cited authority throughout the run of the most significant publications devoted to homosexuality and male culture, Hirschfeld’s Jahrbuch and Brand’s Der Eigene.

John Henry Mackay (1864–1933) is the nom de plume for John Henry Farquhar. Although both his real and assumed names are Scottish (because of his father), he was raised in Germany and wrote in German. Heavily influenced by Max Stirner (1806–1856), he supported anarchist and radical causes in his fight against bourgeois liberalism. In the early twentieth century, he planned the publication of series of six works of literature under the pen name “Sagitta” that focused on the “nameless love” between men and male youths. They were declared obscene in 1909, but he managed to publish them in 1913 as a collection called Die Buecher der namenlosen Liebe (The Books of the Nameless Love). His most famous novel, Der Puppenjunge (The Hustler, 1926), gives a detailed account of the many and varied venues in which teenage boys prostituted themselves in Berlin, including the streets, the new shopping arcades, the bars, and the clubs. Although self-identified as a leftist anarchist, Mackay was united with his more conservative fellow masculinists in his rejection of liberalism.

One of Mackay’s supporters was Benedict Friedlaender (1866–1908).8 Friedlaender was trained as a zoologist and worked with the ideas of Gustav Jäger, the man who had popularized Kertbeny’s vocabulary of “homosexuality” and “heterosexuality” among the sexologists. Initially, Friedlaender cooperated with Hirschfeld and published a number of articles in the Jahrbuch, but he became increasingly estranged from the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. His Renaissance des Eros Uranios (Renaissance of Eros Uranios), published in 1904, was a manifesto for masculinist culture and one of the most cogent critiques of Hirschfeld and his work. Imbued with the spirit of Nietzsche, Friedlaender favors the aphorism as a stylistic gesture. Married and the father of a son, Eugen Benedict, Friedlaender chafed at the strict sexual categories that he believed medicine had foisted upon modern men. Suffering from an inoperable cancer of the intestine, he committed suicide in 1908.

Friedlaender also supported the work of Hans Blüher (1888–1955), who caused a major uproar in 1912 when he argued in Die Wandervogelbewegung als erotisches Phänomen (The “Wandervogel” Movement as Erotic Phenomenon) that homoeroticism was the bond that united male youth groups. His two-volume sequel, Die Rolle der Erotik in der männlichen Gesellschaft (The Role of Eroticism in Masculine Society, 1917/19), titillated and shocked Germany’s intellectuals with the argument that male-male erotic desire was the important glue holding together human society.9 A rightist, he greeted the arrival of National Socialism with approval, but the estimation was not reciprocated. The Nazis regarded him as a danger to youth and didn’t allow him to publish during the Third Reich, although he was allowed to continue private practice. In this capacity, he apparently occasionally provided support for young German men who were discovering their sexual interest in other men in the 1930s.10

The leader of the pack was Adolf Brand (1874–1945), who published Der Eigene, which appeared from 1896 to 1933 and can thus lay claim to being the oldest serial devoted to male-male desire in the history of the West. In 1903, he established the Gemeinschaft der Eigenen. As in the case of the journal, the society’s name can be translated in a number of ways: The Community of the Special, The Community of the Self-Owners, The Community of the Free, The Community of the Exceptional, and so on. In any case, Brand’s Community combined an “anarchistic philosophy of freedom and the cult of the Nordic man.”11 Like Friedlaender, Brand was married, considered himself masculine, rejected medical categories of sexuality, and didn’t appreciate the category of the third sex. In 1907 he “outed” Chancelor Bülow and Philipp Eulenburg-Hertefeld, which resulted in substantial court cases that brought the occurrence of sex between men among German aristocrats to the attention of readers throughout Europe. Brand ultimately spent time behind bars for his efforts. Like Blüher, he was sympathetic to the National Socialists, but they treated him with suspicion, confiscating many of his documents and banning his publications.12 He died during an Allied bombing attack in 1945.

Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch appealed tremendously to these writers, who were smitten by the phantasy of the superman as blond beast. The concept of der Eigene, although taken from Stirner’s philosophical work, overlapped extensively with Nietzsche’s Übermensch.13 Brand himself wrote a poem called “Der Übermensch” and published it in Der Eigene.14 A typical article in Der Eigene was Edwin Bab’s “Frauenbewegung und männliche Kultur” (The Women’s Movement and Masculine Culture), which summed up the difference between the two gendered movements: “The women’s movement is leading us back to ancient Jewish ideals, the movement for male culture to ancient Greek ideals.” Although this sounds ominously as though it would fit into prevalent anti-Semitic rhetoric of the time, Bab actually wanted to see a union of these two cultures and movements which he claimed would lead to “a truly human culture.” He indicated where the philosophical underpinnings of these remark came from in the closing line of his essay: “a truly human culture. Followers of Nietzsche would say, superhuman.”15 Despite Bab’s hopes for a union of the Jewish feminine and the Greek masculine ideals, most in the movement adulated the Übermensch primarily because of his hypervirility and his opposition to any sort of gender inversion.

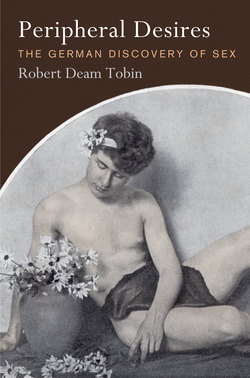

Figure 2. “The masculine ideal,” in Der Eigene, vol. 6 (1906). Personal collection of author.

In addition, the Übermensch appeals because he is beyond good and evil, rejecting the ascetic moral system imposed by the priestly caste upon the herd. Even Hirschfeld cites a Nietzschean aphorism critiquing morality in his 1896 treatise, Sappho und Sokrates (Sappho and Sokrates): “That which is natural, cannot be immoral.”16 Typically, Hirschfeld relies on arguments based on the natural and the biological in his defense of same-sex desire. Friedlaender’s 1904 masculinist study, Die Renaissance des Eros Uranios, follows Nietzsche even further in taking on morality itself as a product of the ascetic spirit and the priestly type. Whereas Brand emphasizes the radical individualism of the superhero, equating the man who loved men with the man beyond good and evil, Friedlaender concentrates in Nietzschean terms on the confining power of the priestly class, its ascetic approach to life, and the role of women in embracing this ideology. He argues that such asceticism creates a class of “the stunted,” men whose ability to love other men has atrophied under the influence of heterosexual moralistic obligations. Nietzsche and his followers often literalize this distrust of the priestly class as an attack on the Jews, who supposedly are responsible for one of the most insidious forms of priestliness—Christianity. The belief that women are particularly prone to submit to the teachings of the priests underscores the misogynist tendencies of this group. With the exception of Mackay, most of the masculinists exhibit these anti-Semitic and misogynist inclinations. In addition, the brilliant dénouement of Nietzsche’s Genealogie der Moral (Genealogy of Morals), where he identifies science as the new, nihilist religion of the modern age, influences many of these masculinist thinkers, who urgently reject the medical and psychiatric efforts to treat them. Following Nietzsche’s lead, they see such scientific efforts as deleterious continuations of the tradition of religious strictures against sexual behavior.

The Civilizing Legacy of the Greeks

Let us return for a moment, though, to the period before Nietzsche’s thought reset the image of the Greeks. Throughout the nineteenth century, Greece provided legitimization for same-sex love and sexuality. Almost everyone in that era who thought about same-sex desire felt obliged to comment on the prominence of same-sex sexual acts in ancient Greek culture. Those who wanted to justify or condone such sexual acts found tremendous legitimizing authority in accounts of sapphism and platonic love. Even those who condemned such inclinations found it necessary to address and explain their open presence in a culture routinely held up as a model for Germany in particular and the West in general.

Even though Zschokke’s Eros is set in nineteenth-century Switzerland, the Greek precedent colors this novella too. Not only do various characters cite ancient Greek examples throughout the text, but the whole work is constituted as a response to Plato’s Symposium. In Eros, as in the Symposium, a series of characters discuss the significance of male-male love, although in the case of the nineteenth-century story the occasion is a dreadful crime of passion in which an older man has murdered his beloved younger friend, rather than the celebration of Agathon’s victory in a dramatic competition. In the Swiss story, a wise man has the last word, mirroring Socrates’ role in the Symposium; tellingly, it is not the character based on Hössli, Holmar, but the moderate narrator, Beda: “Go ahead Beda, you be our Socrates at our symposium.”17 Holmar in fact is styled as the intemperate Alcibaides, who interrupts Plato’s Symposium by arriving drunk at the end to put the group’s wisdom into question. When Holmar shows up late to the discussion group in order to sing a defense of sensual relations between men, his demand for wine serves as a hint to the reader that he has taken on the role of the drunken Alcibiades: “I’ll gladly take a glass!”18 This is all of course an ironic inversion of Plato’s text, which cannot have pleased Hössli, especially since Holmar is not even beautiful like Alcibiades.

Hössli himself argues that ancient Greece provides the most convincing evidence on the nature of male love: “No phenomenon in all history is more inexplicable in our days than this love of the Greeks,” he declares with a certain ironic detachment.19 Summing up the thoughts of his contemporaries, Hössli continues: “We believe (sadly enough) either that the Greeks had a different nature than the general, eternally unchangeable nature that we now have, or that they sacrilegiously defiled their nature.”20 He states his own actual position about Greek love more forcefully later: “If it was nature then, it is still nature now.”21 The unchangeability of male-male love proves that it is just and natural, according to Hössli. Repeatedly, Hössli forcefully rejects critiques of sexual attraction between men by citing the Greek precedent.

By midcentury, though, the terrain began to shift. To be sure, Kertbeny, Ulrichs, and Hirschfeld still mention the Greek example when it suits them. Kertbeny provides historical background when he makes such statements as “it is well known that the Greeks named such female homosexuals ‘tribades’” and “such homosexuals were known among the Greeks as ‘paiderastos.’”22 Ulrichs bases his vocabulary of the “urning” on Plato’s Symposium, in which Pausanius defines “uranian” love as the higher love that men have for men. Later in the nineteenth century, Magnus Hirschfeld would rely on the classical tradition for his first book, Sappho und Sokrates oder Wie erklärt sich die Liebe der Männer und Frauen zu Personen des eigenen Geschlechtes? (Sappho and Socrates or How Can One Explain the Love of Men and Women to Members of Their Own Sex?). Published in 1896 under the pseudonym “Th. Ramien,” some consider it “the founding manifesto of the modern gay movement.”23

On the other hand, Westphal, Krafft-Ebing, and others in the medical community rarely devoted more than a few sentences to Greek examples. As scientists, they wanted hard empirical evidence, rather than speculation based on classical texts. From their perspective, the Greek examples provided at most some evidence of the permanence of the diagnosis that they were using. Because many homosexual emancipation activists, such as Ulrichs and Hirschfeld, worked closely with their contemporaries in the realm of the natural sciences and medicine, they too began to devote more and more time to non-Greek examples of same-sex desire.