Читать книгу Peripheral Desires - Robert Deam Tobin - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction. 1869—Urnings, Homosexuals, and Inverts

The British sexologists Havelock Ellis (1859–1939) and John Addington Symonds (1840–1893) observed at the end of the nineteenth century that “Germany is the only country in which there is a definite and well-supported movement for the defense and social rehabilitation of inverts,” adding that “the study of sexual inversion began in Germany and the scientific and literary publications dealing with homosexuality issued for the German press probably surpass in quality and importance those issued for all countries put together.”1 If we assume Ellis and Symonds are correct, the question arises, why was Germany—and more generally, German-speaking central Europe—so fertile a ground for homosexual subcultures at the turn of the century? What factors helped construct the modern forms of sexuality that were emerging in this time period in central Europe? What intellectual, cultural, philosophical, religious, and social developments informed the ways that scholars, writers, artists, political actors, and other individuals thought about sexuality in the second half of the nineteenth century in German-speaking cultures?

One of Ellis’s patients wrote about Berlin, “here are homosexual baths, pensions, restaurants, and hotels, where you can go with one of your own sex at a certain fee per hour. Berlin is a revelation.”2 One aristocrat claimed in 1897, after having spent forty years traveling throughout the world, that the life of “urnings” (people with the bodies of one sex and the souls of another) in Berlin was “more extensive, freer and easier than anywhere else in the Orient or the Occident.”3 In 1904 physician Paul Näcke published an article titled “A Visit with the Homosexuals of Berlin” in Archiv für Kriminalanthropologie und Kriminalistik (Archives for Forensic Anthropology and Criminology), in which he describes attending a meeting of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, Magnus Hirschfeld’s (1865–1935) advocacy group for homosexuals. According to Näcke, between two and three hundred people were in attendance, “including fifteen ladies”; they listened to a speech by a former Catholic priest about sexuality and the Church. Näcke met couples who considered themselves married, as well as a shy young girl of seventeen or eighteen, discovering this world for the first time herself. Näcke reports on bars catering to homosexuals, places where homosexuals could pick up soldiers hoping to earn some money on the side, and dance establishments where young men “honored with great passion Terpsichore,” the muse of music and dance.4 He mentions that homosexual balls took place at least once a week when the season started in November, some of which attracted as many as 700 guests and were known throughout Europe.5

In the same year, Magnus Hirschfeld (1865–1935) corroborated Näcke’s account in a popular book called Berlins drittes Geschlecht (Berlin’s Third Sex). Hirschfeld describes a metropolis in which well over 50,000 male and female homosexuals lived, often in harmony with their “normal sexual” friends and family. They formed long-lasting pairs, gathered in social parties in milieus ranging from the working class to the aristocratic, supported a lively subculture of cross-dressing entertainers and transvestite balls, frequented their own cafes and bars, placed personal ads in local papers, and patronized large numbers of sex workers, many of whom came from the underpaid military.

By the end of the century, regularly appearing periodicals discussed same-sex desire. In 1896, Adolf Brand (1874–1945) began publishing Der Eigene, an anarchist publication that quickly became devoted to, as its subtitle soon clarified, “masculine culture.” The journal’s title cannot be translated adequately, because of its unusual use of the word eigen, which most frequently means “own” as in “my own.” Less frequently the word can mean “peculiar” (or even “queer”) as well. Most translations attempt to incorporate both senses of the meaning, as well as Brand’s acknowledged debt to Max Stirner’s anarchist treatise, Der Einzige und sein Eigentum (which has been translated as “The Ego and His Own”): “The Special,” “The Exceptional,” “The Personalist,” “The Free,” or “The Self-Owner.”6 In 1899, Hirschfeld and his colleagues at the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee began publishing its own more scholarly journal, Das Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen (The Yearbook for Sexual Intermediary Types).

The activities and writing surrounding same-sex desire and sexuality in that nineteenth- and early twentieth-century German-speaking realm of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Switzerland produced a plethora of sexual terminology. While certainly there was extensive work on sexuality in other countries as well—in addition to Ellis and Symonds, one thinks of Paolo Mantegazza of Italy, Ambroise Tardieu of France, Arnold Aletrino of Holland and Edward Carpenter of England—those writing in German conceptualized sexual vocabulary first. Karl Maria Kertbeny coined the term “homosexual” in 1869 and was the first to employ the vocabulary of “heterosexual” in writings that were published in 1880. Not surprisingly, the term “heterosexual” took much longer to catch on; in Berlins drittes Geschlecht, aimed at a popular audience, Hirschfeld still prefers the term “normal sexual” to “heterosexual.” By 1903, Eric Mühsam and Edwin Bab are debating each other in print about “bisexuality” (Bisexualität).7 The terms “fetischism” (Fetischismus), “masochism” (Masochismus), and “sadism” (Sadismus) make their first appearance in any language in the world in Psychopathia sexualis by the sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1840–1902). Krafft-Ebing’s enormously successful compendium of sexual disorders, which went through many editions and translations and within a few decades was found in libraries in communities all over the globe, also introduced the concepts of homo- and heterosexuality to many readers. Hirschfeld was the first to coin the term “transvestite” in his 1910 volume on cross-dressing called Die Transvestiten. Other languages and cultures soon borrowed these terms, where they successfully formed the base for a modern global discourse of sexuality. Freud’s subsequent influential conceptualization of the Oedipal crisis and the id, the ego, and the superego was just the icing on a vast cake of sexological vocabulary whipped up in German and Austrian kitchens before the First World War.

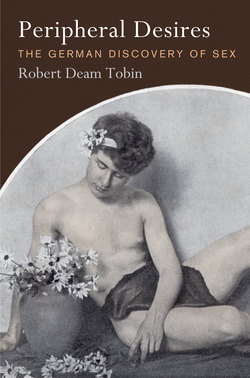

Figure 1. Der Eigene, vol. 6 (1906): A Book for Art and Masculine Culture. Personal collection of author.

In the decade between 1898 and 1908, over one thousand works were published on homosexuality, most written originally in German.8 Even many of those works written by non-Germans were published first in Germany. The work by Ellis and Symonds cited at the beginning of this Introduction had to be published first in Germany under the title Das konträre Geschlechtsgefühl (Sexual Inversion [1896]), before Ellis could find a way to publish it in English. Scandalized by it sexual content, Symonds’s heirs purchased and destroyed the entire run of the English edition printed in 1897.9 Eventually, Ellis slipped it into his English-language collection, Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1905). In publishing in Germany, he followed the example of Edward Carpenter (1844–1929), whose Homogenic Love and Its Place in a Free Society, which was privately printed in an extremely limited run in England in 1894, was much more publically available in Germany as Die homogene Liebe und ihre Bedeutung in der freien Gesellschaft in 1895. This publication activity, as well as the other evidence of a lively homosexual subculture in Germany and Austria, underscores the importance of the question: What cultural phenomena powered this tremendous amount of work done on sexuality in German-speaking central Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century?

1869 and Sodomy

The year 1869 saw the publication of a number of important documents that can provide a useful introduction to the phenomenal increase in discussions of sexuality in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century German-speaking world. A century before the famous Stonewall Riots in New York City’s Greenwich Village ignited the gay liberation movement, three authors published texts in German that would help lay the foundations for modern discourses of sexuality, making intelligible the very claim to gay liberation. Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825–1895) published two brochures defending the legal rights of urnings. In the same year, Ulrichs’s “comrade” Karl Maria Kertbeny was the first person in any language to use the word “homosexual” in print; he employed it in two lengthy pamphlets urging the decriminalization of sodomy in the penal code that was being written for the North German Confederation. Finally, in an 1869 article that Michel Foucault has claimed can stand in for the birth of the homosexual, the psychiatrist Carl Friedrich Otto Westphal diagnosed two patients as sexual “inverts”—one, a woman who had always felt like a man and loved other women, and the other, a man who cross-dressed as a woman compulsively, even though it repeatedly landed him in jail. These initial attempts to describe same-sex attraction constructed the groundwork for modern sexual identities, establishing the discursive framework that still informs many intellectual, academic, cultural, and political discussions regarding sexuality.

A quick look at these documents provides an introductory snapshot that sheds light on the structures informing the emergence of modern sexual identities. To be sure, none of these authors is unknown in the history of sexuality. Nevertheless, the actual writings of Ulrichs, Kertbeny, and Westphal have rarely been the object of sustained scholarly scrutiny. Usually there is merely an acknowledgement of Kertbeny’s linguistic contribution to the history of sexuality and a reference to Foucault’s citation of Westphal. Compared to Westphal, Ulrichs and Kertbeny are particularly neglected, for their works have until recently been much harder to obtain. While Westphal’s medical analyses of same-sex desire were published in journals that were widely distributed in the late nineteenth century and are thus generally available at research libraries around the Western world, the radical political pamphlets of Kertbeny and Ulrichs were much less likely to be collected by libraries and are thus virtually impossible to locate in the original nowadays. They have been reprinted a few times, notably by Hirschfeld in the decades preceding the First World War and more recently by Verlag rosa Winkel in Berlin, but even these reprinted editions are not necessarily available, even in the best research libraries in the United States. Translations into English by Michael Lombardi-Nash and others of some of the most important works are also still not always easy to obtain.10 The digitalization of rare texts means many of these documents have recently become easier to find again.

These essays by Ulrichs, Kertbeny, and Westphal repay close reading because they reveal many of the tendencies that helped shape the contour of modern notions of sexuality. They ask questions that have historically been asked about homosexuality: Is homosexuality a sin, a crime, a sickness? Is sexual orientation a product of nature or nurture? Can a person’s sexual orientation change? Are gay men effeminate? Are lesbians masculine? Do gay men and lesbians have anything in common? Are homosexuals a threat to children? Are they a threat to the nation and national security? Do homosexuals have human rights? Is the free expression of sexuality a human right? Can religion accept homosexuality? These early documents indicate the outlines of the debate on sexuality possible in 1869 Berlin: the assumptions made by Ulrichs, Kertbeny, and Westphal about sexuality reveal the intellectual choices available in mid-nineteenth-century Germany.

These documents were written in the wake of an event that might seem entirely unrelated to questions of sexuality: the otherwise largely forgotten Austro-Prussian War of 1866. Prussia trounced Austria in this war, revealing to a startled Europe its revivified military prowess. The Hohenzollerns of Berlin annexed Frankfurt, Hanover, Hesse, Nassau, and Schleswig-Holstein to their already considerable German possessions beyond Prussia itself, while the Habsburgs of Vienna lost forever any influence in the Germanic realm outside of Austria. With Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898) at the helm, Prussia began to unify the rest of the Germanic principalities as the North German Confederation, which would form the basis of the German Empire established in 1871 at the close of the Franco-Prussian War. The Habsburgs, meanwhile, weakened by their loss, restructured their possessions in 1867, shifting their attention toward the Balkans. Faced with a mounting insurgency, they agreed to grant the Hungarians autonomy and created the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

In Epistemology of the Closet, queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick intuits a link between the emergence of the vocabulary of homosexuality in 1869 and the foundation of the German Empire in 1871.11 In fact, sodomy played a role in the momentous political changes following the Austro-Prussian War. Both new governmental entities, Austria-Hungary and the North German Confederation, needed to revisit their legal codes as they restructured themselves. Sodomy was a flashpoint for legal discussions concerning the role of the state in crimes of the flesh. Until the beginning of the nineteenth century, most of German-speaking central Europe relied on the 1532 legal code of Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire (1500–1558), which had established the penalty of death by fire for a person who slept with an animal, a man who slept with a man, or a woman who slept with a woman. By the Enlightenment, legal theorists, especially Cesare Beccaria (1738–1794) in his work Dei delitte e delle pene (Of Crimes and Punishments) of 1764, began to question the overlap between church and state, calling for the decriminalization of many sexual deeds.

Frederick the Great (1712–1786), hoping to modernize the laws within Prussia, encouraged scholars to think about the theoretical basis for legal reform. Such canonically important texts as Immanuel Kant’s “Was ist Aufklärung?” (What Is Enlightenment?) emerged in response to a footnote in an anonymous piece—actually by Johann Erich Biester (1762–1814)—questioning the state’s role in marriage. Eighteenth-century German intellectuals saw that the role of the state in regulating personal, gendered, and sexual behavior pertained directly to modernity and the Enlightenment.12

Prussian legal thinkers of the eighteenth century did not eliminate the role of the state from marriage, nor were they willing to follow Beccaria and decriminalize sodomy. Some countered Beccaria’s arguments that sodomy was merely a sin and of no interest to the state by arguing that it diminished the country’s population and thus harmed it. Prussia’s sodomy laws remained on the books, although the death penalty for sodomy was repealed in 1794.13 As the nineteenth century progressed, sodomy laws took on national significance. Louis Crompton demonstrates how England prided itself on the fact that it, in contrast to decadent France, prosecuted sodomy offences.14 Presumably, similar motivations justified the hard line on sodomy in Prussia and Austria.

Outside of Prussia and Austria, changes in German law did emerge, however, inspired by reforms in France. In post-revolutionary Napoleonic France, Beccaria’s Enlightened reasoning gained traction. Jean-Jacques Régis de Cambacérès (1753–1824) had the task of restructuring the French civil code after the French Revolution; it came to be known as the Code Napoléon. Removing many feudal relics in the legal code, it also decriminalized private, consensual, noncommercial sex between unmarried adults, even adults of the same sex. When Napoleon’s armies swept through much of Europe, he installed his new legal code; many principalities kept or emulated parts of them even after the French left. Baden, in southwestern Germany, retained the Code Napoléon, although legislators there altered many aspects of it, in order to grant women more protections than were available in the French original, which—for all its liberality in sexual matters—remained quite patriarchal.15 Those Prussian lands west of the Rhine that had fallen under the direct control of Napoleonic France also kept the Napoleonic legal code when they returned to Prussia, meaning that even Hohenzollern possessions had quite different legal codes. Wurttemberg and Hanover retained the spirit of the Napoleonic laws, criminalizing only public indecency rather than sexual acts between consenting adults.16

In Bavaria, Anselm Feuerbach’s criminal code of 1813 attempted to delineate clearly between the “immoral” and the “illegal” and correspondingly decriminalized sodomy entirely. The 1813 annotations to the new Bavarian penal code declared, “as long as people through lewd behaviors transgress only their internal duties to themselves—the commands of morality—without hurting the rights of others, nothing is determined by this present law book; self-abuse, sodomy, bestiality, consensual unmarried sex are all serious transgressions of moral commands but as sins they do not belong to the sphere of external legislation.”17 Isabel V. Hull notes that Feuerbach consistently mentions sodomy when he lists examples of sexual misdemeanors that should be understood as sins, not crimes. For Feuerbach, sodomy represents, according to Hull, an “archetypal example of the liminal delict, the one that defined the line between two categories.” While Feuerbach eventually recanted and proposed revisions to his own legal code in 1824 that recriminalized male homosexuality, his subsequent conservative revisions did not become law.18

Thus, the German-speaking world was at a cross-roads regarding crimes of the flesh in general and sodomy in particular when legal experts in the North German Confederation and Austria-Hungary began to review their penal codes. Both Prussia and Austria continued to criminalize sex between men, along with other carnal delicts, while a broad swath of German principalities, including Prussian possessions west of the Rhine, had adopted Enlightenment reforms regarding sex in their legal codes. For many interested in the law, sodomy became a primary exhibit in the public debate concerning whether the new legal codes of central Europe would be liberal, secular, and modern—or not.

In preparation for the establishment of a unified code of penal law in the North German Confederation, the Royal Prussian Deputation for Public Health had investigated the matter of sodomy laws, and recommended that the paragraph criminalizing sodomy be dropped, noting that the law did not criminalize “degenerate” sexual acts between men and women or between women and that it similarly left masturbation up to the conscience of the individual.19 The list of authors of the report included such scientific luminaries as the Berlin physician and scientist Rudolf Ludwig Karl Virchow (1821–1902). The minister of justice, Gerhard Adolf Wilhelm Leonhardt (1815–1880), apparently initially concurred with the commission and had himself adopted a liberal policy on sodomy in Hanover in 1840.20

The restructuring of the Habsburg Empire as the Austro-Hungarian Empire was similarly the occasion for rethinking the legal code. In 1856, paragraph 129 I b of the Habsburg Empire had prohibited “lewd behavior [Unzucht] with the same sex,” calling for prison sentences lasting from one to five years.21 Krafft-Ebing reports that in the 1860s the government, relying on the advice of a medical commission, proposed the elimination of these penalties for sodomy, among other points arguing that “from various sides, it is maintained that the action prohibited by this paragraph is a natural need for a class of people.”22 Hubert Kennedy reports that the minister of justice, Anton Emanuel von Komers (1814–1893) had proposed decriminalization on June 26, 1867. By 1870, however, a new minister of justice, Eduard Herbst (1820–1892), had rejected the proposal.23

Ultimately, the efforts of all those working to decriminalize sodomy were in vain. The Austrian efforts to decriminalize same-sex acts were rejected and the only “reform” was the rewriting of the language to make sexual acts between women—as well as those between men—illegal. The Prussian government chose to ignore its own commission, concluding that sodomy “exposed such a degree of degeneration and degradation and was so dangerous for morality that it could not remain unpunished.”24 Ulrichs assumed that the law remained in place in order to placate orthodox religious interests. Krafft-Ebing apportions the blame more specifically on conservative minister of culture Heinrich von Mühler (1813–1874), who had special responsibility for issues of religion and education. Mühler wrote to Minister of Justice Leonhardt on April 12, 1869, urging retention of the sodomy paragraph “in the interest of public morality.”25 Prussia’s Paragraph 143 became Paragraph 152 in the North German Confederation’s penal code, which a few years later became Paragraph 175 in the German Empire’s penal code; Paragraph 175 continued to criminalize sodomy in Germany until 1969.26 In Austria, decriminalization began in the 1970s.27

Both Kertbeny and Ulrichs report that, upon deciding to retain the sodomy laws in the new unified North German legal code, the framers of the new code justified their decision with the conclusion: “While decriminalization can be justified from the standpoint of medicine and through some arguments taken from the theory of law, the legal consciousness of the folk judges these acts to be not merely a vice, but also a crime.”28 A century before the publication of Foucault’s Histoire de la sexualité, these bureaucrats knew very well that the institutions of law, medicine, religion, and the state were competing for the control of sexuality.

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and the Urning

The future of the sodomy laws in the North German Confederation was on Ulrichs’s mind when he composed his two brochures in 1869. Ulrichs, who lived from 1825 to 1895, was extraordinarily committed to the rights of urnings and urningins, his words for men who sexually loved other men and women who sexually loved other women. He took the term “urning” from Pausanius’s speech in Plato’s Symposium, which claims Venus Urania is the goddess devoted to the masculine love of men. Ulrichs’s word for men who were sexually attracted to women was “dioning.”

A lawyer by training, Ulrichs began publishing a series of pamphlets in 1864 demanding that the rights of urnings be respected. He continued publishing until 1879—all twelve of the pamphlets were subsequently collected and published as Forschungen über das Räthsel der mannmännlichen Liebe (Studies on the Riddle of Male-Male Love).29 In these writings, Ulrichs unfolds a theory of sexual desire explaining same-sex attraction, a theory that he hopes will combat civic and religious prejudice against urnings. His publications became a clearinghouse for information about urning life throughout the world. He proposed such practical initiatives as a monthly journal devoted to urnings (Prometheus, of which only the first issue, called Uranus, appeared in 1870). On August 29, 1867, he went to a convention of German lawyers in Munich, revealed himself to be an “urning,” and publicly called upon his colleagues to denounce the Prussian anti-sodomy laws. Far ahead of his time, he was hooted out of the convention hall. His openness about his own identity as an urning caused him difficulties. The Freies Deutsches Hochstift in Frankfurt, a prestigious liberal cultural institution, refused to admit him, saying that the organization had rules concerning the admission of men and women, but no provisions for people of other sexes.30 More concrete and specific charges concerning sexual activities were probably behind his resignation from his job as a civil servant in 1854.31 The same allegations probably prevented him from being named mayor of the German town of Uslar in 1865.32 Ultimately, he gave up on Germany and, like so many bourgeois northern European homosexual men, moved to Italy, where he died impoverished and forgotten by most, although Krafft-Ebing occasionally exchanged letters with him and Symonds even visited him.

Ulrichs’s 1869 texts both focus on the Zastrow case. In January of 1869, Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Ernst von Zastrow (1821–1877), a lieutenant in the Prussian army, was accused of anally raping and brutally murdering a five-year-old boy named Emil Hanke.33 The crime was so notorious that the verb zastrieren briefly came to mean “to rape homosexually” (rhyming with the German word for “castrate,” it could be rendered as something like “to zastrate”). An outraged public demanded vengeance against this Zastrow, as well as all other “Zastrows.” Zastrow denied having committed the crime and could prove he had been on the other side of town a half an hour before the crime was committed. Citing Ulrichs, he insisted in his defense that he was an “urning”—a man sexually attracted to other men—and that the mob misinterpreted his sexual nature to think he was sexually attracted to children. Despite his claims of innocence, the court convicted Zastrow. The prosecutors proved he could have gotten across town to the scene of the crime within thirty minutes and located a number of Zastrow’s personal effects near the corpse.34

Ulrichs, who had coined the term “urning” a few years before, wrote two lengthy pamphlets about Zastrow in 1869, one called Incubus and the other called Argonauticus, boldly defending the legal rights of the accused and carefully delineating the argument that urnings were not murderous pederasts, indeed not pederasts at all. As Kennedy explains, whatever Ulrichs thought about Zastrow’s innocence, he was sure that the man had not received a fair trial. Ulrichs’s willingness to take on the challenge of defending the rights of someone accused of such an atrocious crime is especially remarkable. Not that he was condoning the rape and murder of children, of course—he was at least initially convinced of Zastrow’s innocence. When Zastrow was ultimately convicted and sentenced to fifteen years in prison, Ulrichs was willing to abandon him, suggesting that if Zastrow had committed these atrocities, he couldn’t be an urning. With his liberal instincts, Ulrichs knew how important it was to fight against the lynching mentality of the mob; with his legal training, he had the tools to lead such a fight.

The core of Ulrichs’s argument was his insistence that the populace misunderstood urnings and thus was willing to blame an urning like Zastrow for any horrendous crime. At the beginning of Incubus, Ulrichs defines urnings as “men who as a result of their inborn nature feel drawn by the force of sexual love exclusively to male individuals.” An urning’s body is that of a man, but “his erotic drive is that of a female being.”35 Ulrichs confirmed Zastrow’s suspicions that he was an urning. Ulrichs noticed, for instance, that the newspapers reported that Zastrow had “a shadowy, catlike appearance,” which Ulrichs concluded was nothing other than his innate femininity. Like a girl—Ulrichs argued—Zastrow had religious tendencies and enjoyed spiritual music.36 These generalizations about gender were an important part of Ulrichs’s defense of Zastrow, because he argued that the delicate tender feminine nature of an urning made it practically impossible for him to commit violent atrocities.

Ulrichs underscores Zastrow’s own argument that, as a member of the “third sex,” he is attracted to men, as a woman would be, not to prepubescent youths.37 Ulrichs’s claim that the feminine sexual desire of an urning is natural and innate allows him to argue the basic injustice of suppressing an integral part of one’s desire: “Lifelong suppression of the erotic drive cannot be demanded of anyone.”38 At the same time, he approvingly cites a newspaper editorial that supported his arguments on the sodomy laws with the liberal observation that “one must have the right to control one’s own body.”39 From these rights arguments, he draws a series of practical conclusions: an accused urning deserves to be protected from the irrational rage of the mob and the police should not be keeping lists of otherwise innocent urnings.40 He is more than willing to work with allies in the Catholic Church, such as the priest in Mainz who agrees that urning love as described by Ulrichs cannot be a sin.41 His belief in the possibilities of a religious acceptance of urnings goes so far that he enthusiastically reports on two urnings in Moscow, both Protestants, who had married each other: “They had thereby created on their own a sanctioning form for the urning love bond, which urnings miss so deeply.”42 Ulrichs concludes Argonauticus with a list of additional activities that he proposes: he wants to establish a legal defense fund for urnings in legal trouble, he hopes to organize a boycott of Germany should the North German Confederation recriminalize sodomy, and he would like to further the development of urning community by introducing urnings to their “circles” from Hamburg to Munich.43

Ulrichs was consistently involved with leftist politics and civic affairs. He tried to get a job working for the Frankfurt National Assembly, which was founded after the 1848 revolution. In 1867, he spent January 25 to March 20 and April 24 to July 5 in prison, “because of anti-Prussian agitation in the press and in the societies.”44 Ulrichs spent years attempting to receive legal redress for his incarceration in 1867; he also wanted back the books and papers, especially those on uranism (love between urnings), that were confiscated during this time. He was apparently in the small town of Burgdorf studying for his law exams when the revolutionary activities of 1848 broke out in Berlin, but his subsequent political battles with Prussia and the forces of reaction make clear his progressive sympathies.45 He even sent one of his 1869 writings, Incubus, to Karl Marx, who passed it on to Friedrich Engels. Engels responded to Marx on June 22, 1869: “That’s a very curious ‘urning’ whom you have sent me. Those are extremely unnatural revelations. The pederasts are beginning to count themselves and they’re finding that they are a power in the state. Only organization is lacking, but according to this it seems already to exist secretly.” Engels fears that the new slogan will be guerre aux cons, paix aux trous-de-cul (French in the original: “war on the cunts, peace to the assholes”) and remarks that “it’s lucky that we are personally too old to have to fear that with the victory of this party we would have to pay bodily tribute to the winners.” He concludes that such piggishness, such a Schweinerei, is only possible in Germany.46 Engels’s references to “pederasts” and his fears of rapacious urnings exacting tribute show that he doesn’t understand Ulrichs’s argument, for the feminine urning is supposed to be quite a different species from the pederast, and delicate and nonviolent at that. Nonetheless, Ulrichs’s effort to reach out to Marx shows his interest in cultivating support from leftist political thinkers. Marx’s willingness to send the publication on to Engels suggests he does not dismiss Ulrichs’s radical sexual proposals out of hand, even if Engels’s response is curt and derisive.

Ulrichs sets down in his writings a vision of same-sex desire that resonates powerfully throughout the following century. While his assumptions on gender are traditional, his notion that an innate, natural, fixed and biologically provable sexual desire can ground a claim to human and civil rights that ensures equal protection under the law and in the eyes of religion still remains a basic structure for many apologists for homosexuality. His calls for the creation of a stronger sense of community among urnings and the establishment of a legal defense fund for urnings remain relevant today. Arguing first for the elimination of sodomy laws and then for the right of urnings to marry, his practical concerns resemble those of twenty-first-century Western gay rights organizations.47

Karl Maria Kertbeny and the Homosexual

Karl Maria Kertbeny (1824–1882) was born a Benkert, into a German-Hungarian family in the Habsburg Empire. An enthusiastic proponent of Hungarian nationalism, he changed his name to the Hungarian-sounding Kertbeny and devoted himself to promoting the Hungarian cause, including translating and championing Hungarian literature throughout Europe.48 Habsburg police reports give an instructive summary of his life: “Benkert, Karl Maria, also known as Kertbent and Remkhazy, writer from Pest, was a partisan for democracy and the Hungarian insurrection of 1848.”49 He wrote biographies of such Hungarian nationalist poets as Sandor Petöfi (1823–1849) and published anthologies of Hungarian poetry. Although he claimed to have medical training (for which reason some historians of sexuality have listed him as one of the physicians who helped medicalize homosexuality), he did not practice medicine and instead supported himself as a man of letters. This was not a lucrative career path, for which reason Kertbeny’s usual pattern can be summed up as Herzer does: Kertbeny would (1) arrive in a European city, (2) make contact with local literary and leftist political figures, (3) borrow money, and (4) get out of town when the creditors showed up.50

Despite this pattern, Kertbeny enjoyed relative stability from 1868 to 1874, when he lived in Berlin, in part to encourage the German intelligentsia to support the Hungarian cause. There he became embroiled in the discussions concerning the fate of the sodomy laws in the North German Confederation, publishing two lengthy pamphlets on the subject, addressed to Leonhardt, the Prussian Minister of Justice, encouraging him to decriminalize sodomy. It is Kertbeny’s lasting contribution to the history of sexuality that he is the first person in any language known to have combined the Greek prefix homo (same) with the Latin noun sexus (sex) to create a word describing someone who is sexually attracted to members of his own sex. He refers, for instance, to “the natural riddle of homosexuality [Homosexualität].”51 At other times, he uses the term Homosexualismus (homosexualism), as well as the adjective homosexual and the noun, der Homosexuale.

Given that Kertbeny supported himself primarily as a translator and man of letters, his linguistic coinage perhaps deserves more respect than it usually receives.52 Although the term is often dismissed as an ugly linguistic hybrid, it joins a successful set of global vocabulary that similarly combines Greek and Latin roots to describe modern phenomena: the Greek auto (self) and Latin mobilis (to move) form “automobile” and Greek tele (far) and Latin visio (to see) stand behind “television.” Men who were products of a nineteenth-century central European education based on the classical tradition that consisted of a variety of Greco-Roman elements were in a strong position to name technologies that changed the course of history. Kertbeny was not working on his own in developing his terminology, as he and Ulrichs had met in the early 1860s and considered each other “comrades.”53 In fact, prior to its use in public in 1869, the term “homosexual” appears in an 1868 letter from Kertbeny to Ulrichs, although Ulrichs never adopted the word.

In print, Kertbeny writes, “in addition to the normal sexual drive of all of humanity and the animal kingdom, nature seems in her sovereign whimsy to have given a homosexual drive [den homosexualen Trieb] at birth to certain male and female individuals, to have bequeathed upon them a sexual fixedness, which makes the affected physically as well as psychologically unable, even with the best of intentions, to achieve a normal sexual erection.” Kertbeny continues by saying that this condition “exposed them to a direct horror of the opposite sex and made it therefore impossible for those affected by this passion to escape the impressions that particular individuals of the same sex have on them.”54 In this passage, a number of characteristics of Kertbeny’s “homosexual” emerge: first, homosexuals can be of either sex—there isn’t a conceptual distinction between male sodomites and female tribades, to use an earlier vocabulary. Additionally, homosexuals have sexual “drives.” The drive transcends the barrier between mind and body, affecting both equally; it is, as Judith Butler notes in a discussion of Freud, “precisely what is neither exclusively biological nor culture, but always the site of their dense convergence.”55 This drive is responsible for the mental “horror” of the opposite sex and the physical inability to achieve an erection in “normal” situations. The homosexual drive stands in contrast to the “normal sexual” drive, but, despite its deviance from the “normal,” it is natural.

In personal letters, Kertbeny discourages Ulrichs from relying too heavily on the claim that sexual desire is inborn, arguing that such a claim might not redound to the benefit of homosexuals: “there are people with an innate bloodthirstiness…. One doesn’t let these people do whatever they want or follow their desires, and even if one doesn’t punish them for intentional acts if their constitution is proven medically, one does isolate them as much as possible and protect society from their excesses.” Kertbeny concludes that “nothing would be won if the proof of innateness were successful.”56 In his open letter, however, he does assert that nature implants the homosexual drive at birth. However, as we shall see in Chapter 4, Kertbeny’s conception of sexuality is more open to cultural influences than Ulrichs’s understanding of innate gender inversion.

Despite his wariness of arguments relying on innate desire, Kertbeny asserts that “the homosexual [der Homosexuale] is a fixed nature who, however much he strives, can never prefer a woman.”57 Any hope of convincing the homosexual to change his desire is hopeless. At the same time, Kertbeny allays the fears of the “normal sexuals” by assuring his readers that “normal sexual” desire is also fixed, so that there is no danger of sexual contagion.58 Significantly—especially in light of the Zastrow scandal that caused Ulrichs to write so prolifically in 1869—there is also no danger that Kertbeny’s homosexual will abuse children, because the male homosexual’s desire is fixed on virile men. The notion of a fixed sexuality serves a number of important political purposes for Kertbeny: homosexuals can’t be changed, heterosexuals don’t need to worry about seduction, and children are safe.

Kertbeny uses a noun to describe the sexuality as well as the sexual person, writing that “history teaches us that along with normal sexuality [Normalsexualis], homosexualism [Homosexualismus] is and was present always and everywhere among all races and climates and could never be suppressed even by the most bestial persecutions.”59 Kertbeny does acknowledge some level of cultural specificity in the forms that homosexuality takes, arguing, for instance, that homosexuals among more southerly peoples like the Greeks tend to prefer younger men, while homosexuals among more northerly peoples like the Germans are fixed on mature men.60

Kertbeny believes that the “homosexual,” with his (or her) natural, fixed sexual identity deserves the protection of the modern legal state—the kind of state, that is, that was emerging in Germany and Austria-Hungary. He praises the Napoleonic penal code for decriminalizing many sexual acts. Similarly, he extols Feuerbach’s 1813 penal code in Bavaria. For Kertbeny, the modern legal state had “no other goal than to protect rights.”61 He views homosexuality as a matter of human rights: “Human rights [Menschenrechte] begin with the human being, and the most immediate aspect of a human being is his body.”62 Like Ulrichs, Kertbeny insists upon the natural and innate nature of sexual desire in order to make a liberal claim for political rights.

As part of his liberal appeal for a modern state of law, Kertbeny takes on the religious forces that motivate the legal codes that persecute the people he describes as homosexuals. He puts religious prohibitions against homosexuality in the same category as “original sin, the devil and witchcraft,” all of which he consigns to superstition. For him, all these beliefs are merely the product of “the historical development of Judaism and Christianity.”63

Kertbeny’s vocabulary of the homosexual spread slowly at first. Herzer has uncovered some writings in Dutch that use the terms homo sexualisme, homosexualiteit, and homosexuelle verkeering in 1872. The words appear in a ten-volume German book, Scandal-Geschichten europäischer Höfe (Scandalous Stories of European Courts), translated into German by Daniel von Kaszony, one of Kertbeny’s acquaintances. Also a supporter of the Hungarian revolution, Kaszony mentions Kertbeny’s work on same-sex desire in three letters written in 1868.64 This suggests that Kertbeny’s vocabulary on sexuality enjoyed a certain currency among Hungarian nationalists.

Jonathan Ned Katz has usefully summarized the further history of the word “homosexual.” The term really took off when Gustav Jäger, a professor of zoology at the University of Stuttgart, published some of Kertbeny’s work on homosexuality in the second edition of his book Entdeckung der Seele (Discovery of the Soul) in 1880. Jäger, also known incidentally for his promotion of rational dress reform and the usage of natural animal fibers (in particular wool), appropriated Kertbeny’s vocabulary of “homosexual” and “heterosexual.” From there the term spread to other medical and sexological authors, including Krafft-Ebing. In the second edition of Psychopathia sexualis (1887) it shows up in some of the patients’ self-descriptions; Krafft-Ebing himself adopts the term in the fourth edition of 1889.65 The general public came to know the term through sexologists such as Krafft-Ebing. According to Hirschfeld, the word was in general circulation by the last decade of the nineteenth century.66

Although Kertbeny claimed medical standing and used that standing to legitimize his arguments, it is worth lingering on the political origins of the word “homosexual.” It clearly emerges out of a political demand for rights that has nothing to do with pathology or medicalization. Moreover, this demand for rights takes place at the creation of the modern nation state of Germany and the reorganization of the Habsburg Empire into the Dual Monarchy. Kertbeny’s concept of a natural, innate, fixed homosexuality that is deserving of equal rights protection in a secular liberal modern nation-state is intrinsically involved with the political developments taking place in Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Carl Westphal and the Invert

The final of the three authors who published in German on same-sex desire in 1869 is Carl Westphal, whom Foucault cites as one of the begetters of the modern homosexual in a frequently quoted passage from Histoire de la sexualité: “One must not forget that the psychological, psychiatric, medical category of homosexuality was constituted on the day that it was characterized—Westphal’s famous article of 1870 on ‘contrary sexual sensations’ can serve as its date of birth.”67 Foucault not only gets the year wrong, but he also cites the journal incorrectly. The article did not appear in the Archiv für Neurologie (Archives of Neurology), but actually the Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten (Archives for Psychiatry and Neurology), which Westphal himself cofounded and coedited.68 Foucault’s point, however, remains valid—this depiction of “contrary sexual sensations” (or “sexual inversion,” as the term was often translated) became central in the depiction of same-sex desire.

Carl Friedrich Otto Westphal (1833–1890) was a leading figure in the medical institutions of the time. Unlike the outsiders Ulrichs and Kertbeny, Westphal was firmly entrenched in the establishment. The son of a prominent physician, he began working in 1857 for the Charité, the famous hospital that Frederick I had established in Berlin in 1710. By 1869, he was director of the Clinic for Neurology there, a post he retained for twenty years. In 1868, he founded the Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten, which ran until 1983, when it became the European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, under which title it still appears. Although he didn’t name sexual inversion after himself, numerous other human medical features are named after him, including the Erdinger-Westphal nucleus (in the oculomotor nerve), Erb-Westphal symptom (an anomolous reflex caused by nervous system syphilis), and Westphal’s Syndrome (an inherited form of intermittent paralysis). Even from these phenomena, one can see that Westphal was primarily interested in locating the bodily origin of mental and nervous ailments. Westphal’s position at the well-established clinic in Berlin was unassailable and his work with somatic explanations of mental illness gave him the prestige of the hard sciences in which so many advances were taking place.

While the construction of Germany and Austria-Hungary is the political backdrop that stands out most significantly behind the interventions of Ulrichs and Kertbeny, Westphal’s influence should also be seen in the context of the developments in central European research. At the same time as Prussian military might became increasingly manifest and German cities both within and outside of Prussia became more and more prosperous, German universities began to reap the benefits of Wilhelm von Humboldt’s post-Napoleonic reforms of the educational system. German universities attained a preeminent status, especially in the sciences, that they would maintain until well into the twentieth century. The positive developments in the German university system affected Austria too, where the universities enjoyed enormous prestige in the second half of the nineteenth century. Within German psychiatry, the so-called Somatiker, who—as their name suggests—favored somatic interpretations of mental illness, had become dominant in the middle of the nineteenth century.69 The more philosophical legacy of Romantic psychiatry was set aside, at least until Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis could bring back a psychology less based on the body. In 1869, the world was prepared to listen to a leading German psychiatrist’s somatic interpretation of same-sex desire.

The full title of Westphal’s article makes clear its medicalizing and pathologizing agenda: “Sexual Inversion, Symptom of a neuropathic (psychopathic) Condition” (Die conträre Sexualempfindung, Symptom eines neuropathischen [psychopathischen] Zustandes). Unlike Ulrichs and Kertbeny, who allude to medical evidence while not completely accepting a pathological diagnosis, Westphal is convinced that certain forms of same-sex desire are a sickness. Admittedly, he denies that every single case of same-sex desire is pathological: “in order to prevent from the beginning all misunderstandings, I want to state expressly that it is not my idea to identify all individuals who commit unnatural sexual offences as pathological! I know very well that this is not the case.”70 He goes on to explain that, just as there are some pathological thieves and murderers among the many normal thieves and murderers, so there are some pathological sexual inverts among the many people who commit sexual crimes with members of their own sex. Clearly, he has no room for a nonpathological expression of same-sex desire that is also noncriminal.

As a somaticist, Westphal locates the roots of same-sex desire in the body. Sexual inversion is “an inborn reversal of sexual feelings.”71 His first patient, a woman identified as “N,” has known of her desires for other women since childhood. Westphal finds the epilepsy of his second patient, “Ha …,” significant, suggesting a link to neurological dysfunctions. He is certain the condition can be inherited: “We can certainly with some justification make heredity responsible for the origin of the pathological condition of the patient.”72 On a variety of fronts, Westphal promotes and underscores the physical origins of same-sex desire.

The physical and psychological symptoms of sexual inversion include feminine characteristics in his male patients and masculine characteristics in his female patients. Emphasizing the importance of gender inversion, Westphal cites Ulrichs frequently, repeatedly stressing that the male invert has female characteristics and vice versa. His first patient, the woman “N,” speaks the language of inversion precisely: “I feel completely like a man and would like to be a man.”73 His second patient, “Ha …,” adopts the clothes and indeed the entire habitus of a woman. Westphal claims to have noted “Ha …”’s feminine comportment as soon as he saw him knitting in the hospital waiting room.74

More so than Ulrichs and Kertbeny, Westphal is consistent in exploring the possibilities of gender symmetry inherent in the notion of inversion. Ulrichs and Kertbeny repeatedly neglect to include women in their examples, despite acknowledging the existence of women who are sexually attracted to women. Westphal however starts out with a woman and devotes a considerable amount of time to women’s sexual inversion.

Westphal’s essay is an assertion of power, part of a tradition of medical claims to expertise in sexual matters. Significantly, he denies the layperson the ability to determine gender in both cases. He cautions that “N” does not seem unfeminine; about “Ha …” he is only willing to concede that “one can perhaps find something feminine” in his facial features.75 Several decades later, Näcke continues in the tradition of insisting that certain types of expertise are required to determine who is truly gender transgressive: “this requires a specially schooled eye, such as the scholar of inversion, the homosexual himself, the artist, the tailor, and so forth have, but that others—for instance myself—do not.”76

Westphal’s claim to medical power makes counter-assertions of power by his patients all the more interesting, particularly in the case of the woman “N.” Middle-class, she assisted her sister who ran a girls’ boarding school in the country. Having been conscious of her desires for the female sex since her childhood, she regularly indulged in them when she was between eighteen and twenty-three. Since then she had only been able to masturbate. She declares that “female occupations were always distasteful to me; I would like to have a masculine occupation, and have therefore always been interested in mechanical engineering, for instance.”77 Besides the compelling tragedy that this woman’s desire to be a mechanical engineer is pathologized stands the noteworthy fact that her voice manages to cut through the medical language. Westphal has the honesty to report that she does not consider herself insane: “She declared that she herself wanted to go to a hospital, but was however surprised that she had been brought to an insane asylum, as she was not mentally ill.”78 “N” and Westphal are some of the first players in what Gayle Rubin calls the “intensely collaborative enterprise between the doctors and the perverts.”79

While “N” is a middle-class woman working in an educational establishment, Westphal’s second patient comes from a socially more disadvantaged background. Westphal calls him “Ha …,” although he himself claims to be “U.B.” An effeminate cross-dresser, he goes to jail multiple times, for stealing women’s underwear and garments and for “fraudulently” posing as a lady, receiving sentences ranging from two months to five years. “Ha…” claims to have resisted all sexual advances from men,80 confirming Foucault’s observation that Westphal’s invert is characterized “less by a type of sexual relations than by a certain quality of sexual sensibility, a certain manner of inverting the masculine and the feminine in oneself.”81

Many enigmas surround Westphal’s account of “Ha….” The exact details of the arrests and the prison record are confusing and contradictory. Why bother to distinguish between his assumed name “U.B.” and his “real” name of “Ha …,” if both names were changed in order to maintain confidentiality? How serious is the assertion that “Ha …” never had sex with his gentlemen admirers? When “Ha …” claims he would “earn money” at the train station, where he frequently found a “lover,” it sounds like he was in the practice of offering sex for money. Perhaps “Ha …” defined sex such that he could offer physical gratification to his lovers while believing he was resisting their sexual advances. When he boasts that he “earned a great deal of money” while making “demands on gentlemen,” it sounds like he might have been demanding payment after putting the men in a sexually compromising position.82 Blackmail was certainly frequently on the minds of the urnings, inverts, and homosexuals of nineteenth-century Europe. This is not to deny Foucault’s point that, even if sexual activities took place, they were apparently always done in order to support a kind of gender inversion, specifically what “Ha …” calls his passion “for those damnable women’s clothes, which have always been my undoing.”83

Westphal’s case is clearly different from that of Ulrichs and Kertbeny. While Ulrichs relies at times on medical evidence to make his points and Kertbeny claims medical expertise in order to legitimate his position, only Westphal consistently and thoroughly pathologizes same-sex desire. Working within a medical context, he makes no extensive demands on the political situation, although he was against the criminalization of those whose acts were the result of a medical condition like “sexual inversion.” Whereas Ulrichs and Kertbeny present a relatively positive picture of the urning and the homosexual, Westphal’s invert is quite clearly sick. Westphal believes the inversion is probably a symptom of a deeper problem, noting for instance the migraines of “N” and the myriad problems “Ha …” has. Admittedly, Westphal cites passages from Ulrichs in which Ulrichs insists the love of urnings is of the highest and most noble order, but he does so in order to refute the claim. He believes this love is pathological to its core.

Westphal’s writings achieved a more widespread readership than either Ulrichs’s or Kertbeny’s essays. The Journal of Mental Science printed a review of the essay in 1871, using the term “inverted sexual proclivity” as a translation for conträre Sexualempfindung. Havelock Ellis became the first to use the term “sexual inversion” in English in his essay on same-sex desire of 1897. Quickly, “invert” and “inversion” came to be used as frequently as “homosexual” and “homosexuality.”

The widespread availability of Westphal’s writings has led to an overemphasis of the medical tradition in histories of sexuality, at the expense of activists such as Ulrichs or Kertbeny. Strikingly, Foucault does not discuss either Ulrichs or Kertbeny in his Histoire de la sexualité, while granting Westphal paternity to the very concept of homosexuality. It could well be that Foucault was unaware of Kertbeny’s work or unable to access it, but Westphal quotes Ulrichs extensively in his article. The absence of a direct reference to Ulrichs suggests that something larger than ignorance is at work in Foucault’s writing. Writing his introduction to the history of sexuality originally in the 1970s, Foucault has little interest in a romantic representation of nineteenth-century heroes of sexual emancipation. Despite his allusion to “the constitution of a discourse ‘in reverse,’” in which “homosexuality began to speak of itself, demanding its legitimate and ‘natural’ rights, often in the same vocabulary, using the same categories by which it was medically disqualified,”84 an important part of Foucault’s work puts into question the validity of many claims of sexual emancipation and liberation. He is much more interested in the ways in which sexual categories are produced by and play into forces and powers that are much larger than any individual physician like Westphal or lawyer like Ulrichs or homme de lettres like Kertbeny. Instead, he focuses on the medical institutions that create modern homosexuality.

Because of Foucault’s emphasis on the power of institutions, relatively little attention was paid in the immediate wake of his work to the acts of resistance apparent in the case studies of the patients.85 As Rubin has argued, however, there was “a complicated tango of communication and publication” between “the medically credentialed sexologists, the stigmatized homosexual intellectuals, and the mostly anonymous but active members of the burgeoning queer communities.”86 Especially those patients whose sense of entitlement or lack of respect for authority allowed them to disregard the prestige of the medical establishment often picked and chose what they wanted to hear from the physicians. As grateful as they were for the attention of physicians like Krafft-Ebing, most patients wanted primarily to hear that their condition was natural and not deserving of criminality. Rare was the patient who accepted the diagnosis of mental illness.

The Birth of the Homosexual?

The purpose of comparing Ulrichs, Kertbeny, and Westphal is not to establish an exact taxonomy of the urning, the homosexual, and the invert. The language of sexuality in German at the end of the nineteenth century was far too fluid for such an endeavor. By the end of the century, the three terms were often used interchangeably.87 Texts such as Albert Moll’s Die conträre Sexualempfindung (Sexual Inversion) of 1891 and Krafft-Ebing’s Der Conträrsexuale vor dem Strafrichter (The Sexual Invert before the Judge) of 1894 seem to be typical of the period, in that they use urning, homosexual, and invert as synonyms.88 Those who did make distinctions between the terms usually constructed their own idiosyncratic ones. Comparing the three texts published in 1869 can, however, highlight the questions that were in play as sexuality was under construction.

Ulrichs, Kertbeny, and Westphal all share a number of similarities. Born within ten years of each other (between 1824 and 1833), they all lived through the revolutionary fervor of 1848 as young men and became political liberals of varying degrees of radicalism. All writing in German, they were deeply imbued in central European bourgeois culture and highly aware of the political developments of their time. While they were not all physicians, as proponents of the “medicalization” of sexuality have tended to imply, they were professionals—lawyers and men of letters, as well as doctors. Neither aristocratic nor working class, their middle-class upbringing colored their view of the world, no matter what their subsequent financial state and politics became. This shared heritage helped forge the conceptions of sexuality that they articulated and that then spread throughout the world.

The depictions of same-sex desire in Ulrichs, Kertbeny, and Westphal all possess a number of common features. The male urning, homosexual, and invert all have a fixed sexual attraction to men, while the female counterpart has a similarly fixed sexual attraction to women. All three see men who love men and women who love women as belonging to the same overarching category. Ulrichs is certain that the phenomenon can be found in all cultures and all time periods. Westphal’s somatic medical model implies as much. Kertbeny argues along similar lines at times, although, as we shall see, he does allow more room for the cultural construction of identity. For all three authors, sexual desire transcends its physical origins to affect psychology as well.

All three authors agree that the fixedness of sexual desire means that it is unlikely to spread. Both Ulrichs and Kertbeny are quite explicit that those who are not urnings or homosexuals will not change their sexuality. Thus there is no need to fear that urnings or homosexuals will seduce or otherwise recruit new members of their order. Westphal is not so explicit, but his emphasis on the physical, hereditary nature of sexual inversion implies that it is not something one could catch from a neighbor, even if it is a sickness. The authors also concur that a natural, fixed desire should not be criminalized. Ulrichs and Kertbeny, in particular, assert that their urnings and homosexuals deserve political rights and protection from interference by the state or religion. They both make arguments relying on a general notion of human rights and tend to rely on left-liberal elements of the political spectrum. Interestingly, both feel strongly the need to fight for the religious rights of urnings and homosexuals as well. While Westphal was in fact a political liberal, he does not make any explicit arguments for providing rights to his inverts, other than suggesting that medical experts are better than police at handling cases of inversion.

While not the case for Kertbeny, Ulrichs and Westphal emphasize gender inversion as the explanation for sexual attraction between members of the same sex—male urnings have female souls and male inverts have many feminine characteristics, while female urnings have male souls and female inverts have masculine characteristics. For Ulrichs, Zastrow’s way of walking and speaking are perhaps more telling than his sexual deeds. Westphal too is immediately struck by the effeminate behavior of “Ha …”, and particularly notes his peculiarly womanly voice, while leaving open the question of whether his patient is sexually active with men at all. Similarly, “N” has never been interested in feminine occupations and aspires to a traditionally masculine career.

The status of the sexual partners of the urnings and the inverts is not clear at all. Although Ulrichs does refer to an urning couple marrying each other, he seems at other times to imply that urnings are often sexually attracted to “dionings,” or men with both male souls and male bodies, rather than to other urnings. Indeed, according to Ulrichs, the sexual partner of the urning is often a soldier in financial need. Nor is Westphal particularly interested in pathologizing the women with whom “N” sleeps or the men who approach “Ha …” in the train station. In general, Westphal portrays the sexual partner of the invert as duped and defrauded. As mentioned before, Kertbeny differs from his contemporaries in this point, and does not rely too heavily on gender inversion to explain the attraction of his homosexuals for members of their own sex. For him, a whim of nature causes the male homosexual to desire men and the female homosexual to desire women. While this has less explanatory power, it does get him out of the conundrum of explaining who the partners of homosexuals are—presumably other homosexuals.

It should be clear by now that this snapshot of several texts on same-sex desire published in 1869 just begins to scratch the surface of what was going on in the second half of the nineteenth century in German-speaking central Europe. Subsequent sexologists, activists, and literary authors take the the ideas articulated in 1869 to promote a vision of same-sex as natural, fixed, related to gender-inversion, analogous with race, comprehensible in liberal bourgeois terms, and manageable by medical and political interventions.