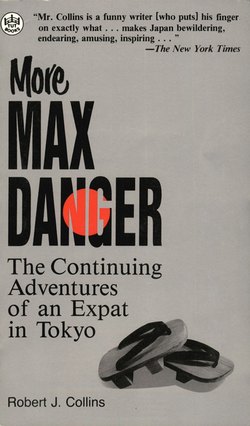

Читать книгу More Max Danger - Robert J . Collins - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAnother Dimension

IT HAD BEEN RAINING—a driving, splashing, windswept torrent of water—for twenty-four hours. Muddy rivers cascaded down the mountain roads, engulfing and threatening to submerge the abandoned automobiles scattered randomly in the newly-formed lakes and ponds of the countryside valleys.

It's the "tail of the typhoon," everyone said comfortably, as if knowing why the heavens had opened in such spectacular fashion was enough to banish concern.

Nevertheless, Max Danger, feeling for all the world as Noah must have felt, surveyed the situation with considerable concern. (He briefly reviewed his experiences of the last week to make certain he had not overlooked a dream or vision involving cubits and shipbuilding.)

Max and thirty-nine of his company stalwarts were bouncing along the mountainside roads of the Izu Peninsula. It was company travel (trouble) time. Perched on the" gaijin seat" in the front of the bus, Max watched the driver negotiate the hairpin curves. Great stretches of the road were under water, thereby blurring the nice little guidelines one considers when navigating in the mountains—ditches and edges of cliffs. In fact, swinging wide on curves created waves of water washing over the edges and onto the tops of tall pine trees growing many meters below. It was truly, and alarmingly, breathtaking.

The driver's head rocked back and forth in an attempt to keep his vision on track with the wipers sweeping across the windshield. Since the windshield was the size of a barn door, the driver nearly left his seat each time the wipers reached the end points in their cycle. Fortunately, he had the steering wheel to hang on to. He had taken off his Mickey Mouse gloves and was gripping the wheel with actual flesh.

The bus hostess had stopped prattling over the intercom at about the same time as the driver doffed his gloves. The relative silence was a blessing, but it also emphasized the drama inherent in the escapade. It did not alleviate Max's feelings of concern to watch her peering intently through the windshield and hear her whisper hidari (left) or migi (right) to the driver as he wheeled the vehicle around blind corners. She was also doing something unusual for bus hostesses. She was sweating.

Max saw the jumble of stalled automobiles at the same time the driver did. Luckily the wipers were in the middle of their cycle. Max's foot jammed imaginary brakes—the driver hit the real ones. The bus slewed sideways, its rear end clipping the boulders at the very edge of the cliff. Sliding and banging in this fashion, the bus entered the lake formed in a hollow in the roadway. It came to a stop against a red Honda submerged to its windows in water. Eight other automobiles were in the lake, and about a dozen people were standing under trees on the "upside" of the cliff watching the action.

(A question was raised in Max's mind regarding the situation, although the question has nothing to do with this story. For the fun of it, let's take a poll. How many readers—raise your hands—think it's better to : a) stand together under trees on the "upside" of the cliff and watch vehicles plow into each other, or b) send someone, or a group of someones, up the road a few meters to the curve, and signal drivers to stop? Remember, those are your vehicles being plowed into.)

In any event, progress ceased. The rain, demonstrating its power, gushed with renewed vehemence. Bubbles of water the size of golf balls bounced from the lake's surface. Serious Hirose, from the mahjong group in the back of the bus, broke the silence. "Why we stop?" he enquired.

Looking back on it now, Max realizes there was never any real danger. One can be stranded far from civilization for days (or months) in other parts of the world, but it's virtually impossible in Japan. Over the next hill or around the next curve there's bound to be a Sony shop or pachinko (pinball) parlor.

It did take about an hour to agree upon a plan of action. The bus was capable of sporadic radio communication with its partner containing the other half of Max's company stalwarts. The second bus had encountered a landslide ten or eleven kilometers back, on the same road Max had just traveled, and the thinking was that each group should fend for itself. It was 4:30 in the afternoon.

No, there was no real danger, but there was extreme discomfort. Max's group disembarked from the bus into knee-deep (or waist-deep, depending upon who it was) water. Twenty-two males and eighteen females began a trek on foot down the mountain to a village rumored to be four or five kilometers away.

The wind was blowing uphill, and the trick was to lean forward enough to keep moving, but not enough to fall on your face. Little gaps in the blowing of the wind did send some of the hikers sprawling, particularly the larger people who had to reduce wind resistance by leaning forward at a more radical angle. Max sprawled once, but a heavy girl from the Accounting Department hit the pavement four times.

No part of anyone's body was dry. It would not have been so bad if it had been warmer, but as the sun set, the temperature dropped to below 10 (Centigrade). Head down, water sloshing around his ankles, more of the stuff blowing against his chest, Max began to shiver. The girl in front of him, who was wearing only a thin blouse and short skirt, was actually turning blue. Colds would be inevitable, but Max was worrying about pneumonia.

The inn at the village, which turned out to be about ten kilometers away, had seven rooms and, to no one's surprise, they were all occupied. Space on the lobby floor was available, however, and the old wooden structure became literally a port in the storm. Long lines immediately formed at each of the two toilets in the facility.

Normally a merry lot, no one in Max's company was having fun. A number of people surrounded Mr. Kitagawa, a former Ministry of Finance official and now a senior advisor to the company, and rubbed his arms and legs. He did not look good. One young secretary, pregnant, was wrapped in spare futons and given hot tea. Even Serious Hirose, a tough little character, was having problems. His shivering rattled the shoji against which he was sitting.

It was nearly as cold in the building as it was outside. Obviously, it was not the cold of mountain peaks in Nepal; it was more like the damp and bone-chilling cold of the west of Scotland. Keeping wet clothing on was unthinkable, taking it off was impossible. It was going to be a long evening.

So now, Gentle Reader, you have a picture of the circumstances. With those circumstances in mind, consider the impact the following had on Max and his little group.

The inn was constructed in the third year of the Meiji era (1870). It partially burned down in 1894, but was rebuilt immediately. Because it was against a cliff, but only a few meters from the road, it had suffered from the effects of periodic earthquake-induced landslides which tumbled rocks and mud onto its structure. Parts of the inn had to be repaired every ten or fifteen years.

The inn had its heyday during the first few years of the twentieth century. Located at a strategic point in a mountain pass, it originally serviced walking merchants and peddlers on their way through the territory.

Automobiles damaged business—there were few reasons to stop at that location. The later bussing of tour groups virtually destroyed any thoughts of growth or prosperity. There was no place to park buses, and there was nothing in the area scenic enough to attract tourists. The inn now attracted only locals who came for sentimental reasons, or because it was the only public facility in the general neighborhood. Very few concessions had been made to "modern" amenities.

It did have one thing, however, and that one thing was a godsend to Max's group. It also provided Max with the opportunity to experience something one usually only hears about.

At the rear of the building, connected to the structure and covered by relatively new roofing of plexiglass, was a natural hot-spring bath. It may be stretching things to call the bath a lifesaver, but it sure changed an intolerable situation into something approaching sensual ecstasy.

The pregnant secretary was led to the bath first, followed immediately by Mr. Kitagawa. The blue girl, who had been wearing the flimsy blouse and mini-skirt, had to be carried to the bath. Serious Hirose and Max, the shiverers, joined the next group of a half-dozen people. Within fifteen minutes, all twenty-two males and eighteen females were shoulder-to-shoulder in the hot water. Some wore underwear, some did not.

Max has been wrong before, and will probably be wrong again. Once he had been unable to imagine "an innocent society of folks romping together in rice paddies by day and splashing together in communal baths by night." A lot of laughs had been generated by Max's bumbling into the ladies' bath at a hot-spring resort during the "company trouble" of a year ago.

But lounging in the heat and steam of a countryside bath, rain banging against the plexiglass roof, sensations gradually returning to the extremities, and the blessings of heat penetrating to flesh and bones, Max entered, albeit temporarily, a different and new dimension. Concentration on private pleasures in public circumstances is an accommodation the Japanese have mastered.

"Feels good," stated the tea girl from Keio University, Max's companion on his immediate left.

"Yes, it does," replied Max, eyes closed and a hot towel on his head.

It will never be the same.