Читать книгу Aftermath - Robert J.D. Firth - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2

Оглавление“The danger? But danger is one of the attractions of flight.”

— Jean Conneau, 1911

Aftermath; About 70 crash investigators from Spain, the Netherlands, the United States, and the two airline companies were involved in the investigation. Representatives from the insurance companies, the two air carriers, the press, and other investigators from the US, Holland and Spain all converged on the site within hours. Literally, there were hundreds of them. The search for the truth had begin. Blame had to be laid and payments made. This is the aftermath:

So what happened? Over time, the facts showed that there had been various misinterpretations and false assumptions. Analysis of the CVR (cockpit voice recorder) transcript showed that the KLM pilot was convinced that he had been cleared for takeoff, while the Tenerife control tower was certain that the KLM 747 was stationary at the end of the runway and awaiting takeoff clearance. It appears KLM's co-pilot was not as certain about take-off clearance as the captain.

Subsequent to the crash, first officer Robert Bragg, who was responsible for handling the Pan Am's radio communications, made public statements which conflicted with statements made by the Pan Am crew in the official transcript of the CVR.

In the documentary Crash of the Century (produced by the makers of Mayday), he stated he was convinced the tower controller had intended they take the fourth exit C-4 because the controller delivered the message to take "the third one, sir; one, two, three; third, third one" after the Pan Am aircraft had already passed C-1 (making C-4 the third exit counting from there).

The CVR shows unequivocally that they received this message before they identified C-1, with the position of the aircraft somewhere between the entrance and C-1. Also, in a Time article, Bragg stated that he made the statement "What's he doing? He'll kill us all!" which does not appear in the CVR transcript.

The investigation finally concluded that the fundamental cause of the accident was that Captain Van Zanten took off without takeoff clearance. ( see KLM findings in appendices) The investigators suggested one of the reason for his mistake might have been a desire to leave as soon as possible in order to comply with KLM's duty-time regulations, and before the weather deteriorated further. I personally doubt this as no pilot ever would attempt a take-off if he thought that there was any possibility that another aircraft might be on the runway.

One thing worth mentioning here is that accident investigators always have one thing in mind; if at all possible, blame the pilot! Of course, as at Tenerife, this was clearly the case. Human error is, in point of fact, the causative factor in most air accidents. Faulting the pilot however has other major advantages and for this reason this is one of the cardinal rules of aviation accident investigation. This is especially easy to do if the pilot is conveniently dead! You will find that pilot error is almost always listed as the official cause. Mostly, this is the case but not always. Download a few of the “blue book” findings from the NTSB and look this up for yourselves. The reason for this bias , if it can be called that, is due entirely to product liability concerns. If the aircraft is at fault then the consequences financially could be monumental, extending far beyond insurance considerations. For example, when the tail fell off the Airbus 300 back in 2001 as it took off from New York, the American Airlines pilots refused to fly the aircraft and the entire fleet was parked.

After that, no one wanted to buy or lease Airbus products. The investigators tried to blame the co-pilot for pushing too hard on the rudder pedal. This, of course, is asinine and absurd. The aircraft was well below its max operating speed, MMO, the speed that all the control surfaces can safely be moved to their full deflection without structural damage. The bloody vertical fin and rudder just fell off in some light to moderate wake turbulence. Airbus put extreme political pressure on the US Government who then coerced the NTSB into blaming the pilots- both of whom were conveniently dead. No one believed for a minute the NTSB’s probable cause.

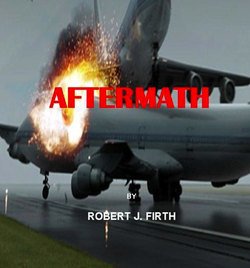

Over time, this accident faded out of the public view but, in 2010, another Air France Airbus crashed into the South Atlantic and, for a time, it was thought that the aircraft had suffered structural failure due to turbulence. As it turned out, flight recorder was eventually recovered and it appears that instrument failure and pilot error were to blame. Also, in 2011, the new giant Airbus 380, which can carry almost a thousand passengers, on two decks, was being operated by QUANTAS and had an engine blow up, (photo above) damaging the wing, and coming close to causing a major catastrophe. You can bet that frequent flyers will avoid the 380 for a while.

Getting back to Tenerife, where pilot error was definitely the cause. Other major contributing factors were:

•The sudden fog greatly limited visibility. (major)

•The control tower and the crews of both planes were unable to see one another.

•Simultaneous radio transmissions, with the result that neither message could be heard.

The following factors were considered contributing but not critical:

•Use of ambiguous non-standard phrases by the KLM co-pilot ("We're at take off") and the Tenerife control tower ("OK").

•Pan Am mistakenly continued to exit C-4 instead of exiting at C-3 as directed.

•The airport was (due to rerouting from the bomb threat) forced to accommodate a great number of large aircraft, resulting in disruption of the normal use of taxiways.

The Dutch authorities were naturally reluctant to accept the Spanish report blaming the KLM captain for the accident. The Netherlands Department of Civil Aviation published a response that, whilst accepting that the KLM aircraft had taken off "prematurely", argued that he alone should not be blamed for the "mutual misunderstanding" that occurred between the controller and the KLM crew, and that limitations of using radio as a means of communication should have been given greater consideration. (See the KLM report in the appendices)

In particular, the Dutch response pointed out that the crowded airport had placed additional pressure on all parties, KLM, Pan Am, and the controller; sounds on the CVR suggested that during the incident the Spanish control tower crew had been listening to a football match on the radio and may have been distracted. The transmission from the tower in which the controller passed KLM their ATC clearance was ambiguous and could have been interpreted as also giving take-off clearance.

In support of this part of their response, the Dutch investigators pointed out that Pan Am's messages "No! Eh?" and "We are still taxiing down the runway, the Clipper 1736!" indicated that Captain Grubbs and First Officer Bragg had recognized the ambiguity; if the Pan Am aircraft had not taxied beyond the third exit, the collision would not have occurred. (Number five in our list of circumstances, which, all told, created a tangible and discernable path of happenings, inextricably leading to death on a massive scale.)

Speculation regarding other contributing factors includes: Captain Van Zanten's failure to confirm instructions from the tower. The flight was one of his first after spending six months training new pilots on a flight simulator, where he had been in charge of everything (including simulated ATC, which, by the way, is the norm, for any simulator instructor), and having been away from the real world of flying for extended periods. This, however, in itself, means little as there is almost no difference between the simulated experience and that of the real world. In fact, in the level C simulators a pilot can obtain his type rating so that his very first flight in the real aircraft will be with live passengers.

Another factor was the flight engineer's apparent hesitation to challenge Van Zanten further, possibly because Captain Van Zanten was not only senior in rank, but also one of the most able and experienced pilots working for the airline.

In point of fact, any rated airline captain with about ten thousand hours and 500 in type is just as good as any other…Anyone can have a bad day or make an error… as did Van Zanten…… On a foggy day, such as this was, caution is doubly important… Clearly, He shoved the power levers up prematurely but we can be certain that, at that moment, he absolutely believed he was cleared for take-off.

A study group put together by the Air Line Pilots Association found that not only the captain, but the first officer as well dismissed the flight engineer's question. In that case, the flight engineer might have been either reassured or even less inclined to press the question further. Again, we will never know…

The reason only the flight engineer reacted to the radio transmission "Alpha one seven three six report when runway clear" might lie in the fact that this was the first and only time Pan Am was referred to by that name. Before that, the plane was called "Clipper one seven three six".

The flight engineer, having completed his pre-flight checks, might have recognized the numbers but his colleagues, preparing themselves for take-off, might have subconsciously been tuned in to "Clipper."

The extra fuel the KLM plane took on added several factors: it delayed takeoff an extra 35 minutes, which gave time for the fog to settle in and it added over forty tons of weight to the plane which made it more difficult to clear the Pan Am when taking off. That fuel also increased the size of the fire from the crash that ultimately killed everyone on board. It took almost nine hours to extinguish the fires.

Captain Van Zanten's reaction, once he spotted the Pan Am plane, was to attempt to take off. There was nothing else he possibly could have done. Although the plane had exceeded its V1 speed, (in this case about 120 ks) it did not yet have adequate airspeed. The sharp lifting angle caused the KLM jet to drag its tail on the runway, thereby reducing its speed even further.

The collision was the inevitable result of physics. KLM, moving at about 120 ks, smashed into the side of the Pan Am aircraft exactly as the artist’s rendering above indicates. It’s a miracle that anyone survived.