Читать книгу Aftermath - Robert J.D. Firth - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

“In flying I have learned that carelessness and overconfidence are usually far more dangerous than deliberately accepted risks.” Wilbur Wright, in a letter to his father, September 1900

LIABILITY & CHANGE

Aftermath; The old bell rang on the ground floor of Lloyds on the morning hours of March 28th, 1977, the day following the worst air disaster in world history. The bell had been recovered from the first ship whose cargo was insured by Lloyds. In this case the ship was the Lustine and she carried a shipment of gold valued at $500,000.

The ship's bell (engraved "ST. JEAN - 1779") was recovered on 17 July 1858. The bell was found entangled in the chains originally running from the ship's wheel to the rudder, and was originally left in this state before being separated and re-hung from the rostrum of the Underwriting Room at Lloyd's. It weighs 106 lb. and is 17.5 inches in diameter. It remains a mystery why the name on the bell does not correspond with that of the ship. (photo right)

The bell was traditionally struck when news of an overdue ship arrived - once for the loss of a ship (i.e. bad news), and twice for her return (i.e. good news). The bell was sounded to ensure that all brokers and underwriters were made aware of the news simultaneously.

The bell has since developed a crack and the traditional practice of ‘ringing the news’ has ended: the last time it was rung to tell of a lost ship was in 1979 and the last time it was rung to herald the return of an overdue ship was in 1989. Of course, the mournful tones from that long sunken wreck’s bell echoed throughout the Lloyds building on the afternoon of the Tenerife crash on March 27th, 1977.

The accessing of liability began on that morning and continued for two years. The issues were clear, the total destruction of two $25 million dollar aircraft and the death of 583 human beings. The aircraft could be replaced but the loss of life was irrevocable and final.

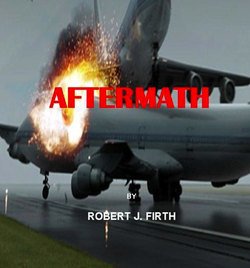

A survivor of the Pan Am flight, John Coombs of Haleiwa, Hawaii, said that sitting in the nose of the plane probably saved his life: "We all settled back, and the next thing an explosion took place and the whole side, left side of the plane, was just torn wide open.

56 passengers and 5 crew members aboard the Pan Am aircraft survived, including the captain, first officer, and flight engineer. Most of the survivors on the Pan Am aircraft walked out onto the left wing, the side away from the collision, through holes in the fuselage structure.

The process of grieving for the families who had lost loved ones began on that day along with the search for answers as to why this senseless accident had happened. The various steps involved in understanding exactly what had happened were easily established. The voice and flight recorders were located and examined. The radio transmissions between the aircraft and the ground controller were crystal clear. Hundreds of investigators and lawyers heard them and they were carefully transcribed and studied. We include them here in Chapter 6.

Although the Dutch authorities were initially and naturally reluctant to blame Captain Van Zanten and his crew, the airline ultimately was compelled to accept responsibility for the accident. KLM’s insurer eventually paid the victims or their families on both aircraft compensation ranging between $58,000 and $600,000.

As reported in a March 25, 1980, Washington Post article the sum of settlements for property and damages was $110 million (an average of $189,000 per victim due to limitations imposed by European Compensation Conventions in effect at the time). This figure may seem low by today’s standards, but adjusted for inflation and devaluation the figure would be closer to one billion.

As a consequence of the accident, sweeping changes were made to international airline regulations and to aircraft. Aviation authorities around the world introduced requirements for standard phrases and a greater emphasis on English as a common working language.

For example, ICAO calls for the phrase "line up and wait" as an instruction to an aircraft moving into position but not cleared for takeoff. The FAA equivalent at the time was "position and hold" (though as of September 30, 2010, this has been changed to "line up and wait" to comply with ICAO standards.

Also, several national air safety boards began penalizing pilots for disobeying air traffic controller's orders. Air traffic instruction should not be acknowledged solely with a colloquial phrase such as "OK" or even "Roger", but with a read back of the key parts of the instruction, to show mutual understanding.

Additionally, the phrase "takeoff" is only spoken when the actual takeoff clearance is given. Up until that point, both aircrew and controllers should use the phrase "departure" in its place (e.g. "ready for departure").

Cockpit procedures were also changed. Hierarchical relations among crew members were played down. More emphasis was placed on team decision-making by mutual agreement. This is known in the industry as CRM, Crew Resource Management.

In 1978 a second airport was inaugurated on the island: the new Tenerife South Airport (TFS). This airport now serves the majority of international tourist flights. Los Rodeos, renamed to Tenerife North Airport (TFN), was then used only for domestic and inter-island flights, but in 2002 a new terminal was opened and it carries international traffic once again, including budget airlines. The Spanish authorities installed a ground radar at Tenerife North following the accident. Like a dangerous intersection, to get a traffic light some kid has to be flattened… Go figure!