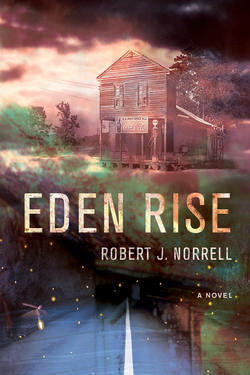

Читать книгу Eden Rise - Robert Jeff Norrell - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4 Baby Gone Home

ОглавлениеAt the funeral home in Norfolk, Virginia, the solemn undertaker led my mother, William, and me into a small, dimly lit room furnished with a few straight chairs and a sofa bearing a design of deep red flowers and olive-colored leaves and vines. Someone in the room was wearing a musky perfume, which made the air feel even stuffier than its eighty degrees. The undertaker introduced us to Mrs. Herndon and Lena, Jackie’s fourteen-year-old sister. His mother was almost six feet, and wide in the hips and shoulders, which made her look strong, not fat. Jackie had strongly resembled his mother, but her features were thicker and fleshier. Her brow was furrowed and her mouth fixed tightly, the big brown centers of her eyes ringed in pink. Mrs. Herndon’s was the saddest face I had ever seen.

I hung back, grasping for words and trying to find the breath to say them, but Mama went straight to Mrs. Herndon and hugged her. The two mothers sat side-by-side and talked quietly, holding hands and passing a box of tissues back and forth. Mrs. Herndon’s hands dwarfed Mama’s, but like hers they revealed themselves as instruments of hard labor. Jackie had said she worked in a laundry.

Soon Mrs. Herndon raised her eyes and beckoned me over. I felt my knees go weak. “Jackie always said good things about you.” Her face was still perfectly sober.

“He was my good friend,” I said.

“Tell me what happened to him at the store that night.” Her voice was sharp, even angry.

I wanted to loosen my necktie so I could talk better, but it didn’t seem appropriate. I just started in, haltingly. I tried to keep my words even and measured. I told her about Alma—who had gone back to California the day after Jackie died, I’d read in the newspaper. I told about the storekeeper shooting at us and how I shot back—too late—and our desperate drive to the hospital.

“Have they charged this Buford Kyle with murder?” she asked.

“Ma’am, they just charged manslaughter.”

She frowned. “What is wrong with you white folks? What made this man think it was okay to start shooting my baby?”

You white folks. I shivered. I had lived most of my life alongside black people. I didn’t want to be herded into the same pen with Buford Kyle or George Wallace, or even my father.

At that moment, a tall black man strode directly to Mrs. Herndon. He spoke to her in a deep voice, glared at me, and then turned back to her. “This who got Jackie killed?”

I cringed. She shook her head in disgust, then looked at Mama. “I’m sorry, Mrs. McKee. This man is Jackie’s father.” She turned back to the man. “I ain’t taking your mess now, Melvin. Don’t come in here drunk, as usual, and expect me to take it.”

Jackie had told me that he hardly knew his father, that he had never lived with the family. I caught a strong whiff of liquor as the man leaned toward me.

“Is you the white man that took my boy to Alabama and got him killed?”

I thought he was going to hit me, and I doubled my fists. But Mrs. Herndon rose and called out for the undertaker, who hurried over with a man so big his suit looked ready to tear at the seams. They hustled Jackie’s father away from us.

“Goddamn. Treated like shit at my own boy’s funeral,” he snarled. He gave me a last brutal look on his way out. “I’m sorry, Tom,” Mrs. Herndon said. Somehow Melvin’s anger had dissipated her own, and she just wanted to talk to me about Jackie. She was proud of his interest in science. I told her how Jackie had helped me pass a geology course the past spring. He had told her he was going to the freedom school to teach science. I decided not to say that Jackie had changed his mind about that, which would have required saying more about Alma and her angry demands. I blamed Alma for Jackie’s death but I didn’t want to go into that now.

The undertaker returned to escort Mrs. Herndon to see Jackie. She stood, took Lena’s hand, and then looked back at Mama and me. “You come along,” she said. I froze. I’d been dreading this for the entire last day. I had never seen a dead body. Bebe had insisted on keeping Granddaddy’s casket closed. I especially didn’t want to see Jackie. I looked at Mama, hoping she would see my fear, but she nodded firmly toward Mrs. Herndon. I had no choice but to go.

Large sprays of roses, carnations, and gladiolas were crowded around the steel-gray casket, which gave the dimly lit parlor the cloying smell of a greenhouse. Mama took my hand and led me to a place discreetly behind Mrs. Herndon and Lena. They whispered quietly to one another as they leaned over the coffin. Finally they stepped aside and Mama pulled me forward.

He looked like a painted doll. The features were recognizably Jackie’s, except his eyes were closed. His skin was so uniformly creamy brown and smooth that it didn’t seem at all real. I had never seen Jackie in a suit, but his body was dressed in a black one with a maroon tie. A red rose lay across his chest. The only thing truly familiar to me was Jackie’s hands, folded on his chest. Now they were perfectly cleansed of the blood that had covered them when I last saw them. But now they looked as if they were chiseled from marble. Strange as it sounds, I would have liked it better if they had been holding a basketball.

I looked as long as I could bear, and then I took another breath and fixed my eyes on a pink gladiola just beyond the top of the coffin. Finally Mama turned us away and we faced Mrs. Herndon.

Mama dried her eyes. “He is so beautiful.”

Mrs. Herndon smiled disconsolately. “Thank you for bringing Jackie back to me.” She looked away for a moment. When she returned her gaze to us, her big eyes were wet again. “Today’s May thirtieth. Jackie’s birthday. He was eighteen today.”

Her words sucked all the air out of my lungs and yanked me back to a memory of Jackie telling me how he got his name.

The Duke freshman team, of which Jackie was instantly the star despite being the youngest member, had played in South Carolina but he had been thrown out of the game—a shock to me given his even temper. He took a swing at a guy who had been pulling the hair on his legs and calling him nigger. He told me later how his coach had taken him aside, reminded him about Jackie Robinson, how whites screamed racist abuse when he started with the Dodgers but how Robinson held his temper and beat the other teams with his bat and his base running, not his fists. Jackie and I were shooting baskets outside my dorm, when he told me this.

“My full name is Jackie Robinson Herndon. Mama was real pregnant with me when he went into the majors in 1947. So, when I was born, she named me for him.” Jackie’s eyes had twinkled. “She always told me if Branch Rickey hadn’t started Jackie with the Dodgers that year, I would have been named for her next favorite Negro, Cab Calloway.” He gave me a half-smile. “Cab don’t sound much like a ballplayer, does it?”

Jackie Robinson Herndon. Breathe, I told myself. Breathe.

On the day of Jackie’s funeral, charcoal-colored clouds dumped rain on the little Baptist church with the fury of a hundred firehoses. But the bad weather didn’t keep away mourners. The church was almost of full of elderly women, who studied me intently as Mama, William, and I entered the church and sat two pews behind the family. “Tha’s him.” The loud whisper of an old woman. “White boy drove him down there.”

The small choir sang plaintive spirituals—“Go Down, Moses” and “Baby Gone Home”—that were punctuated by claps of thunder and Mrs. Herndon’s wails. She kept crying out Jackie’s name and a single word she seemed to be addressing to God: Why? Her shouts and the cracking thunder made me start trembling.

The preacher’s words put me in hell. “They killed Emmett Till and tied him to a fan and threw him in the river . . .”

“They did!”

“They shot Medgar Evers and he died at the feet of his crying babies . . .”

“They evil!”

“They bombed to death those four little girls in the Birmingham Sunday school . . .”

“Help me, Lord.”

“They shot and buried Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman under a mountain of dirt.”

“Oh, God.”

“They shot our Jackie . . .”

The mourners’ responses grew louder with the mention of each martyr and turned into a angry shout with Jackie’s name. My arms and legs shook, my stomach churned, and my ears roared from some inner racket. The lights in the little church glared through my eyelids even when I clenched them shut.

In the awful moments when Jackie was shot, there were things I had to do, actions I had to take that were directed from some deep survival instinct. But now I was trapped in that little church, unable to move. Mama’s firm hand took mine. She leaned in to me. “Breathe, precious. Breathe slow.”