Читать книгу Eden Rise - Robert Jeff Norrell - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue 1993

Оглавление“You can make the difference, Tom,” U.S. Attorney Randy Russell told me. “I know it’s been years, but even now you can do us justice.”

Russell’s urging caused me to lose much of a night’s sleep. I got up that Saturday morning and went to an AA meeting. Let go of it, because you can’t keep it from happening. I hadn’t known that AA lesson the awful summer I was nineteen, when the world seemed to cave in on me. And now Randy Russell was asking me to summon that dead world’s ghosts. At 9 a.m., I called my sister and asked if she had time for a ride down home.

“I need some advice.”

“Sure thing,” said Cathy. “Telling my big brother what to do has always been my favorite pastime.”

I picked her up and we headed southwest out of Birmingham, the midday sun behind us, pitching its yellow rays almost horizontal to the ground. It was the coolest light of the year, the friendliest and easiest to use, though it didn’t last long. It brilliantly illuminated the hardwoods, which had all donned their saffron and auburn and crimson, though many had already shed their leaves.

Cathy eyed me carefully when I edged hard into a turn at Tuscaloosa. We rode due south on the gentle rise and fall of pavement through pine thickets around Moundville and Greensboro. The little towns had run down in the decades since I left, their concrete streets now broken and potted, many storefronts vacant. Three out of four houses begged for paint. Compared to our prosperous suburbs, with our ever-expanding shopping malls and our French-imitation mini-mansions and our very black asphalt streets, these little towns could show us nothing new. Nearly all had lost population since the 1960s. The prosperous whites—including Cathy and me, the remnants of our small-town clan—had departed for more manicured places. I wasn’t sure where the blacks had gone, but most had abandoned that part of the world.

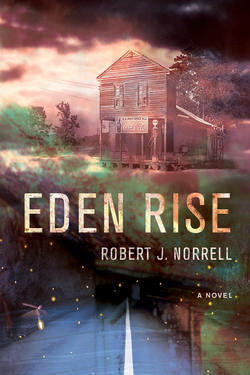

South of Greensboro the rolling of the land became gentler, the landscape more open. We had reached the Black Belt prairie, and soon our own little faded town rose up ahead. Eden Rise sits on the last ripple of that gently rolling prairie before it flattens out entirely. The Virginia planters built a village on the elevation when they gleefully moved to Alabama in the 1830s. They came to take advantage of the charcoal-colored soil that lay atop a great limestone formation. The Virginians expected this “self-liming” soil to combine with the hot sun and the big rains to make an Edenic paradise of cotton—having already worn out the garden soil in the Old Dominion. They brought along their large array of slaves, a fact I discovered when as a confused middle-aged man I decided to research the genealogy of my family. In looking for my ancestors I came across the massive property holdings—of both land and flesh—of the Randolphs, the Ruffins, the Cockes, the Withers, and the other first families of Virginia who were also the first families of this prairie garden. The thousands of Africans were the real cultivators of the new Eden. The owners of the land disappeared on Civil War battlefields, or if they survived, they left after the war for Birmingham or Atlanta or Mobile.

Other whites had soon presented themselves to take control, among them a Scots-Irishman named McKee who spawned my line. They all discovered what the first settlers knew—that, while the soil would indeed grow bumper crops of cotton, it turned into a glue-like mud with the first spring deluge, thus making harvesting the big crop a frenzy of work in the snatches of dry time between long periods when animals and equipment and Africans were stuck in the mud. Of course, by the time I was farming as a young man, improved drainage and wide-wheeled tractors mostly kept us from getting stuck.

The road into Eden Rise looked different from how it did in my childhood. The tin-roofed sharecropper houses had disappeared, and if they had been replaced, it was with a manufactured home, what we called a trailer-house when I was growing up—a rectangular box made of fiberboard and covered with beige aluminum. They were cleaner and nicer than the shacks they replaced, but like their inhabitants they sat unrooted on the land. Little in fact was now rooted in the Black Belt soil. I didn’t know of anybody now growing cotton within thirty miles of where I grew up. Much of the land around Eden Rise, including parts of our own, was used for catfish farming.

Still even an old dirt farmer like me had to admit that the catfish ponds, which covered several acres each, often in groups of three or four, were beautiful on this bright day as the sunlight bounced off the water. I pulled off the road and parked in front of a pond that we owned—though its slimy inhabitants belonged to a corporation based in Mississippi. On the pond’s bank, when most of the other flora had called it a season, lantana bloomed promiscuously. It lit the water’s edge a fiery red.

Having gotten this close to home, I didn’t really want to go into town and drive by our family home, or my grandmother’s, or the courthouse, the scene of so much trouble back in1965. These places would make me remember the injustice, now almost thirty years old, that Randy Russell wanted me to help him correct. I was happy to stop right here, amid the beauty of farmed fish. I got out of the car and stood looking at the water.

Cathy joined me. “So? Talk to me,” she said.

Randy Russell, President Clinton’s recent appointee as U.S. attorney in the Northern District of Alabama, had asked me to meet him at John’s Restaurant in downtown Birmingham. I had just dug into my snapper tails and coleslaw when he smiled tentatively and said he was going to file a criminal case for violation of civil rights in the 1965 Yancey County murder.

I jerked back hard from my food. I thought he had invited me to dinner because he was going to offer me a job on his staff. I had spent the previous evening pondering whether I wanted to give up teaching constitutional law at Cumberland law school.

“What?!”

“Yeah. I’m going to get a conviction this time.”

I was having trouble swallowing my food.

Russell went on. “I just feel like I’m supposed to do something about it. Make up for old wrongs, correct past injustices.”

I guess there had been a long silence at the table when he plunged ahead. “Tom, I’m going to need you to be a witness. You know, the main witness.”

“That was a terrible time in my life. I’m not going back there.”

He looked at me a long moment and then shrugged. “You’re a lawyer, Tom, an officer of the court. You have an obligation as a material witness.” When I didn’t respond, he shrugged again. “I can subpoena you.”

It sounded like a threat, coming from a thirty-something prosecutor who was still riding his Huffy when my best friend was murdered in 1965. I didn’t like it. “I’ve forgotten most of what happened,” I said.

He looked at me without blinking. “You can remember.”

As she gazed at the shimmering water, Cathy tapped her can of Diet Coke. “I heard Russell has an idealistic streak. Son of a Methodist preacher, isn’t he?”

My sister is good-looking at forty-five—tall and shapely in her Gap jeans and crisp Oxford shirt. Gray streaks add character to her thick, dark hair. She runs a usually profitable public relations firm, manages a mostly happy marriage to a busy surgeon, and has raised two generally well-adjusted teenagers. Her success as an adult, especially compared to my own irresolution, has earned my deference to her opinions about the big issues. But since that summer of 1965, I’ve also known she was something of a genius at human relations.

“You said you wouldn’t do it. Why do you need advice?”

“You understand why I don’t want to testify?”

“You’re trying to avoid a hassle.”

“So it’s the right decision?” I said.

“I didn’t say that. You decided, and it’s your decision.”

I looked over toward Eden Rise, hazy in the fall warmth. “What’s the reason to do it? You understand that these trials are just a quick fix for liberal guilt?”

The idea, of course, was not original with Russell. In the last few years, several far more notorious civil rights murder cases—Medgar Evers in Mississippi, the four girls at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham—had been reopened and old racists dragged into court before juries now including blacks. I had followed those proceedings with a distant skepticism, born partly of the assumption that whites didn’t ever get convicted of such crimes and partly from my lawyerly doubts about the efficacy of old evidence—dead witnesses, lost documents, and such. But those killers did at last get convicted, which made people believe they could shut the door once and for all on the past.

I had shoved into the shadows of the past the face of my friend Jackie Herndon, dead now for twenty-eight years. There too were the angry eyes of my father, the lazy face of the prosecutor, the sneers of the attorney defending Jackie’s killer, the contempt of townspeople who thought I had betrayed my birthright. The last thing I needed was to parade ghosts into a federal courtroom. The post-civil-rights-white-punishment-and-redemption trials became major media events. There wasn’t enough whisky in Birmingham to get me through that.

I suspected the insincerity of people using the past for today’s therapeutic needs. These trials were a way for blacks and whites to avoid dealing with the serious human relations problems we faced in the 1990s—failing schools and the indifference to them, drugs and crime, black kids growing up virtually without parenting, smug whites insulated in suburbs like mine. You had the conservatives who now used Martin Luther King’s dream of a color-blind society as their authority for denouncing affirmative action and minority set-asides when they had not agreed with anything King said when he was alive. There were the neo-Confederates who insisted that the Civil War hadn’t been about slavery so they could feel good about being Southern and create cover for their persistent white-supremacist instincts. And all the folks doing backflips to forgive George Wallace for fomenting hatred in the 1960s because later, when blacks had won the vote, he asked to be forgiven. I would never forgive George Wallace for how he tried to ruin my father in the summer of 1965.

The ones most willing to confuse forgiving with forgetting were black. All right, forgive him if you want, but that doesn’t undo what he did in the 1960s. We’re still paying for that, with a lot of the payback going to blacks who remain so outraged at what happened back then that they refuse to acknowledge that history has moved on and some things have gotten better. Just a few months ago, I heard a black preacher declare to a big group that we still had slavery in Birmingham, and he got a rousing response.

People lie about the past so they can lie about the present. They become so selective about what they remember the truth gets lost. For me, the past just meant regret.

All this tumbled out as we communed with the catfish. Cathy nodded solemnly. “I see what you mean about the insincerity.” She studied her Coke can. “But in the world of PR, you tell clients to figure the price of doing nothing. What’s it cost you not to testify?”

I shrugged.

“Oh, come on, Tommy. You risk seeing yourself as a coward, somebody who lost the guts you showed as a nineteen-year-old.”

“Courage is overrated.”

“Bullshit. You don’t believe that.” She shook her head. “The guy subpoenas you, you’ll tell the story like it happened. You’re incapable of lying in court.”

She picked up a rock and threw it far into the pond, setting off a frenzy just beneath the surface. She looked back at me. “Plus you might get something good out of testifying.”

“Like what?”

“On Oprah they call it closure.” Cathy has this way of arching one eyebrow when she is about to nail your dumb ass to the wall. “You’ve been beating yourself up your whole adult life over what happened.”

She and I knew well the side effects of my lifelong recrimination. We called them the three Ds—divorce, drinking, depression.

“Who knows. In a new trial, you might find out you’re not guilty after all.” She flung another rock into the pond and picked a stem of scarlet lantana. “Let’s go look around town.”

We drove around the square. Everything looked a lot different. In 1965 it had bustled and shone, clean and bright. Now the Farmers and Merchants Bank bore the name and logo of a big Birmingham holding company. The windows of the barbershop, shoe store, and hardware store on the south side were boarded up with sheets of plywood. Pasted on them were posters for a rap concert in Selma that was now two months in the past. The grass on the square hadn’t been mowed in a month, nor had the dead leaves under the magnolia been swept up. No flowers bloomed.

The Confederate statue had a six-pointed star spray-painted on its base. “Somebody in town embracing Judaism?” I wondered aloud.

“Gang symbol. See the pitchforks above it?” Cathy’s teenagers kept her well informed.

We drove past the sprawling ranch house we had grown up in—where in the summer of 1965 I argued with my father and where, after Jackie’s death, I was a virtual prisoner. The house now sported purple shutters. Cathy clucked her tongue. “At least they’re painted.” The shutters on the neighboring house were peeling and hanging askew.

We proceeded to the curved, tree-lined drive that rose to a columned mansion from the 1850s. Cathy knocked on the back door and told the live-in caretaker we were going to look around for a few minutes but wouldn’t be coming inside. After a slow stroll around, I said it looked pretty good.

“Needs painting.” She pointed to the upstairs windows.

We sat on the front porch in the ancient glider, once a bright aqua but now a dull, pale blue. It squeaked loudly; we couldn’t glide.

“The Rose of Sharon still blooms.” Just as I pointed that way, a sparrow chirped. “Here-kitty-kitty-kitty,” my grandmother Bebe used to sing in mimicry of the songbird. As a three-year-old, Cathy had changed it to “Loove, Bebe, Bebe, Bebe.”

When I began to hum an old hymn, Cathy cast a sweet smile my way. “I know you don’t want to sell it. I don’t really, either.” She paused to let the sparrow have his say.

“You can’t have it both ways, Tommy. You want to hold on to our past when it’s the memory of Bebe, but then you repress the hard stuff.”

On the way back to the car, she slipped her arm around my waist and leaned into me. “You know your decision is going to be the right one as far as I’m concerned. I’m just pointing out a couple of things to think about.”

We stopped at Dreamland in Tuscaloosa and ate some ribs and watched the Crimson Tide play Mississippi State on television. On Monday I called Randy Russell. Late that afternoon I began to tell him what happened on the highway to Eden Rise on May 24, 1965.