Читать книгу As It Was: A Memoir - Robert M. Pennoyer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4 DAD

ОглавлениеDad never tried to dominate any of his children. He cared deeply about each of us, but his greatest gift to us was the freedom to work out our own destinies, and the sense that he expected us to do what was right.

He never expressed disapproval of anything that any of us ever did. There was a sort of distance in our relationship, which, after all, is far from the worst thing. I loved him, and I knew he loved me, though neither of us ever said it. I wish we had.

He tended to come across as open and affable, someone supremely confident in his own skin: a gentleman, reserved, distinguished looking, refined in his tastes. But his estimable career notwithstanding (a career that was in no way dependent on his connection to the Morgan name), he remained always just a little unsure of himself, and I saw how he needed to draw on my mother’s reserves of strength.

Dad was a doer, and enjoyed working with and for people, for a cause. Someone like Winthrop Aldrich, head of the Chase Bank, would be the chairman of this or that committee, but my father would do the work. Whenever he and I would meet for lunch, we’d walk together to one of his clubs, the Downtown Association or the Recess Club. When you are walking down the street with somebody, you try to fall in step together. It was always I who ended up setting the pace; Dad would endeavor to be in step with me, instead of the other way around. I noticed that he was that way with other people as well; it was as if he was holding something back, holding something in.

This self-effacement flies in the face of all that he accomplished. He never mentioned his law practice to me (his principal work was in the field of trusts and estates), but in the 1950s and ’60s he was managing partner of his firm, where he was admired for always winning his points by suggestion, never by fiat or pressure. (When he died, in 1972, we had his stone engraved with the words “In quietness and confidence shall be your strength.”) He loved the law: “I have never considered any other course as capable of bringing me so much pride and happiness in my work,” he once wrote me; and he loved White & Case: “I shall always want to think of myself as part of its destinies and life,” he wrote Mr. Case. In his spare time Dad served for decades as a trustee of the New York Philharmonic; a governor of New York Hospital; a director and member of the executive committee of the France-America Society and the Alliance Française (he was a chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur); a member of the Council on Foreign Relations; chairman of the finance committee of the Republican Party of Nassau County when it was a major source of funding for national campaigns (he had delighted in teaching our pet parrot to exclaim, “Vote Republican!”); president of the board of Green Vale School; and secretary and trustee of the Pierpont Morgan Library. He was a member of the Order of Lafayette and the Society of Mayflower Descendants, and a founder of the Creek Club in Locust Valley, with its magnificent golf course on a hill overlooking Long Island Sound.

In World War I Dad had held the rank of captain of Field Artillery in the U.S. Army and was a liaison officer with the French army. In early 1942, at the age of fifty-one, a few weeks after Pearl Harbor, he took leave from his law firm to return to active duty with the rank of major in the U.S. Army. He was later promoted to full colonel—assigned to the Pentagon on the staff of General Arnold, head of the army air corps—and for several years was involved in supplying the Chinese and American air forces based in Chungking, the headquarters of the Nationalist government deep in western China. Dad could reach Chungking only by flying to New Delhi and from there over the “hump” across the Himalayas, the Japanese having severed the land route across Burma. In his letters home he sounded happy and fulfilled. In early 1942 he wrote me at St. Paul’s School that he had met some extraordinary people, including a “Colonel” Eisenhower (Ike’s rank before his meteoric rise to four-star general). At the end of the war, for his distinguished service Dad was awarded the Legion of Merit, the highest decoration for noncombat service.

Some twenty years ago, as the head of the management committee of my law firm, I was seated at one of our firm dinners next to Dean Rusk, our speaker that evening, who had been John F. Kennedy’s and then Lyndon Johnson’s secretary of state. He said to me, “I knew your father. I was assistant secretary of state when the war in Japan ended, in early August 1945, and we were having all these meetings over in the Executive Office Building to discuss the terms of surrender and the administration of the Occupation and how to handle the Japanese currency and economy. I was at the head table with John McCloy, who was assistant secretary of war, and your father, who was a subordinate, was right behind us. He handed us a pad of paper with a few sentences that instantly solved the problem we were debating. McCloy said to me, ‘You see, Dean, you’d pay $50,000 for that advice in private practice.’” As Dad wrote my mother at the time, with characteristic modesty, “These are tremendous days and my still being in the service has brought rewards beyond my dreams in the way of experience. I have sat in on some momentous meetings in which the story in some big history has been written. My own part has of course been a minor one, though I expect to be able to show myself words or ideas here and there in historic documents which I have made contributions toward.”

He had reason to be proud because he truly did leave his thumbprints on history. He never tried to advance himself, but his ability and reputation for hard work brought him assignments that would be the envy of most men. In 1944 during the last year of the war he was one of the few War Department staff assigned to the Executive Office Building next to the White House to work with the State-War-Navy-Coordinating Committee, the predecessor of the National Security Council, on postwar planning. Then in the spring of 1945 he was a member of the U.S. delegation under Secretary of State Stettinius that met in San Francisco with our wartime allies to draft the charter of the United Nations. By August he was back in the Executive Office Building where he saw Truman come out on the steps of the West Wing to announce the Japanese surrender, described vividly in the letter he wrote to me on August 15:

I certainly was delighted to get your letter of Aug 2nd and to hear you were back. But what you must be going through in the way of excitement now must be indescribable. You will now I suppose get all the novelty of special missions without the risks and dangers which I must admit relieves me endlessly.

All of the surrender documents have been going through us here and we have been working on them a great deal, including all day Sunday (like old times at SF). It has been very very thrilling, and an experience I wouldn’t have missed.

I had a front row seat on all the surrender excitement—the press photographers, couriers and people were running around the White House West Wing and the street between there and the State Dept. (Executive Street) for several days from Aug. 10th on. Cars were arriving and departing constantly with a lot of what I call the Pullman type with grab handles for the Secret Service people to hang on to as they stand on the running boards, and 4 wireless masts.

My office looks over the West Wing where the Pres’ office is and Executive St. So I finally saw Byrnes take the Jap reply about 6:30 from the State Dept. to the White House, and in fact took a movie of him, surrounded by photographers and flashing bulbs. Then the Pullmans began arriving in a big way and we could identify the big shots piling in to the West Wing of the White House, including Gen. Marshall, Secy. Forrestal, etc. Then the 7 p.m. announcement, and the din and excitement began. We climbed through the window and walked up and down Executive St.

It was swell being in on the kill, and I felt tremendously rewarded for being kept in the service.

Must close. Best love and luck,

Dad had been born in Oakland, in 1890. Ten years before, his father, Albert Adams Pennoyer, had gone West to visit a cousin of his, Edson Adams, one of the original settlers of Oakland, in the 1860s. Albert liked what he saw well enough to settle there. A merchant by the name of Henry Clay Taft took him on as a partner in his then five-year-old department store, renaming it Taft & Pennoyer. In short order, Albert married a Massachusetts woman, Virginia Edmunds, who bore him three sons. The family home was a commodious Victorian, with wide porches, filigree woodwork, and dark furnishings, on a leafy street on a hill overlooking what is now the Berkeley campus. Dad’s father died relatively young, in 1904. His obituaries grandly described him as a “department-store magnate” (by then his store did boast thirty-eight departments, all illuminated by electricity, and plate-glass showcase windows that were the latest thing in display). After his father died Dad was sent to a boys’ school in Geneva, where he developed a love for life in Europe that never left him, then to Lawrenceville, in New Jersey, and to college at Berkeley where he spent a year before transferring to Harvard.

Colonel Paul G. Pennoyer, 1945

My grandmother Pennoyer moved East, first to New York and then to Litchfield, Connecticut, where she lived in a house that is now the town library. She was a very formal, dour, even grim, woman. A Victorian woman, really. She admonished me to always call my sister Dina by her proper name, Virginia, and sternly recommended that I insist on being called Robert rather than Bobby.

Cousin Edson Adams was another story entirely. In October 1944, when I was in San Francisco on my way to the Pacific, my father wrote me, “As you may remember, your mother and I on our recent trip out West had Cousin Edson Adams with us—across the Sierras via Alta, Soda Springs, the Donner Pass to Reno, and Virginia City. If you have a few minutes to spare, do call on him.” I crossed San Francisco Bay to Oakland, which was by then a thriving city, and found him sitting in his office overlooking the bay (at eighty-six he was the oldest active bank president in America). He pointed to a wall that had a photograph of Oakland the way it had looked when he first came there. It was nothing but three wooden shacks and a single pier on wooden piles that jutted out over the mud flats, and in the distance the bay, as yet minus its bridge (to get to San Francisco you had to take the ferry).

My father did extensive research on our early history. The Pennoyers had rude beginnings. They were Huguenots who left Normandy for Wales in the late 1500s in the wake of Catholic persecution. In the early 1600s William Pennoyer, who as a youth had changed his name from Butler to avoid being identified as a witness to a murder, had a son, also named William, who became a prosperous cloth merchant in Bristol and went on to acquire lands in Ireland and interests in saltpeter, gunpowder, and sugar. After the death of the younger William’s wife, by whom he had one son, also named William, he married his illiterate scullery maid. It was she who produced my namesake, Robert, who came over on the Hopewell to Boston in 1635 when he was eighteen.

In 1670 the second William established the first scholarship at Harvard, thanks to his friendship with the college’s founder, John Harvard. It was actually two scholarships, of which he stipulated that “one of them, so often as occasion shall present, may be of the line of posterity of the said Robert Pennoyer, if they be capable of it.” When, decades ago, my two very capable sons, Russell and Peter, applied to Harvard for admission, the first question on the college application form asked whether they were descended from “the said Robert Pennoyer.”

My namesake was no saint. Some years after he arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony he was indicted for something called “jumping the bundling board.” In those days, if you were unable to make it home before dark, you could always stop at the nearest farm and ask for a bed for the night. To separate a sleeping daughter from an overnight guest her parents would put what was called a bundling board down the middle of the bed. Robert jumped it, and to escape prosecution for attempted seduction he fled the commonwealth and resettled in what is now Stamford, Connecticut. The town records for 1648 show that he was “complained against for drinking wine and becoming noisy and turbulent, and abusing the watchman.” His son Thomas Pennoyer was one of twenty-three signers of the deed for the purchase from Chief Katonah of land stretching all the way from Long Island Sound to the northern end of Bedford, New York.

Dad wanted to keep his ties to the West. He took my mother to California on their honeymoon (Niagara Falls was the furthest west she had ever been). They stopped off at Lake Tahoe, where they drove south to Emerald Bay on what was then a dirt road, and later went to Montesol, north of San Francisco, to visit their friends Norman and Caroline Livermore. (One of their sons, Ike, would grow up to marry my sister Dina.)

In the summer of 1935 Dad took the lot of us to a dude ranch in Wyoming, but the next summer he went further west, renting a ranch house on Lake Tahoe, south of Emerald Bay. We roughed it. There was no running water or electricity. The housekeeper kept a cow, and made butter by churning the milk in a three-foot-high lidded tub with a hole in it for the plunger.

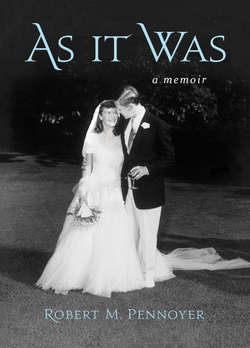

Frances Tracy Pennoyer at the wheel of a Morris during her honeymoon at Lake Tahoe, July 1917

My father loved Tahoe, and that summer he bought land on Rubicon Beach just north of Emerald Bay. The property came with a shack toward the south end of the beach, and Dad commissioned an architect to build a large, attractive, wooden two-story house with about six bedrooms and a second entrance on the second floor for access when winter snows ten to fifteen feet deep buried the front door.

It was ready by the next July—1937. He called it Paradise Flat, a name that conveyed his feelings about the West. For the journey to Tahoe we had to take the overnight to Chicago, then change trains for the three-day trip to the West Coast, passing through the drought-stricken plains during the worst of the Dust Bowl that caused such unspeakable hardship during the ’30s.

The train trip was an adventure. In those days porters on the sleeping cars and dining car staff were all black. In the 1930s these were some of the best jobs available to black Americans. They were kind and considerate, and watched over us. We always had at least two Labradors with us, and took them out for a “walk” on the platform whenever the train made brief stops through the day and night. The porter would stand by the steps at the end of our car, and when the train was about to leave call us just in time to make sure we were not left behind. The dining cars were a luxury unknown today, with white tablecloths and menus for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and separate sittings announced by a waiter walking along the sleeping car corridors ringing a three-tone gong.

Sometime in the ’60s, my parents gave the big house and half the land to my sister Tracy, and the by-then-expanded shack and the rest of the land to my sister Dina, so that their California property went to my California-based sisters, as it should have. They were always fair.