Читать книгу As It Was: A Memoir - Robert M. Pennoyer - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 BOYHOOD

ОглавлениеI was born in the third-floor nursery of my grandfather J. P. Morgan’s house at the corner of Thirty-seventh Street, now part of the Morgan Library and Museum. The date was April 9, 1925. My father, Paul Geddes Pennoyer, was pacing the entrance hall at the foot of the stairs when my grandfather’s head butler, the famous Physick, called down from the second-floor landing, “Sir, it’s a girl!” As my father reached for his hat to go down to Wall Street, Physick added, “Wait, sir, there’s another on the way!”

In due course we newborn twins, Kay and I, were taken home. Home was always “Round Bush,” on Duck Pond Road in Glen Cove, Long Island. Except for the two years my parents lived in Paris when my father ran the French office of White & Case and the four years they spent in Washington (in what my father described as “a minute house in Georgetown”) during the Second World War, my mother lived continuously at Round Bush from 1918 until her death, in 1989.

My parents had married on June 17, 1917, in the Episcopal Church of St. John’s of Lattingtown, in Locust Valley. My grandfather was the senior warden and occupied the first pew on the right (we Pennoyers were relegated to the fourth row). Every Sunday he could be counted on to pass the collection plate at eleven sharp (he was fanatical about punctuality). My brother, Paul, remembered how after the service Grandpa would pour the proceeds into a green felt drawstring bag and deposit it in the Morgan bank the next morning. He had helped found the church in 1912, and was responsible for the intricately carved paneled oak interior he’d had made in Scotland, over the course of five years, as an exact replica of the little Thistle Chapel of medieval knights in Edinburgh, and then shipped to Long Island in bits and pieces. After World War II my mother, who did lovely needlework, embroidered a needlepoint image of the church on the curtain that is mounted on the panels to the right of the altar. It took her three years to complete; she said it was a genuine labor of love.

On her wedding day, she had worn a silk-illusion dress embroidered in a floral motif and trimmed with orange blossoms and genuine seed pearls, fashioned by the venerable Worth of Paris. It was probably the only truly splendid dress she ever owned, and half a century later she donated it to the Museum of the City of New York. She told me she would have preferred a very small wedding but that her mother and father felt people would think they disapproved of the match if they did not invite a few hundred guests.

My father had just graduated from Harvard Law School. For several years he had been training in the army reserve at Plattsburgh and, when America entered the war in April 1917, he had wanted to enlist on active duty, but was dissuaded by his prospective father-in-law, who told him in his customary no uncertain terms, “You had better graduate and finish that chapter.” As a Harvard undergraduate, my father had belonged to the Delphic Club, which Grandpa Morgan had helped to found when he was at Harvard. As a member of the Gas House (as Delphic was known), Dad had become good friends with my mother’s older brother, my beloved Uncle Beak (Junius Spencer Morgan), who one weekend in 1915 brought him home to Matinecock, my grandfather’s estate on East Island in Glen Cove, where he met my mother who was then only eighteen.

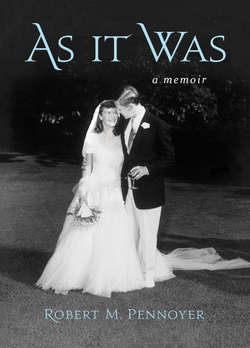

Frances Tracy Morgan at her wedding, June 17, 1917

On their first meeting my father won my mother over by immediately calling her by her nickname “Bowser,” a dog in a favorite English children’s book of hers. (When my mother first met my wife, Vicky, she asked her to call her “Aunt Bowser.”) They got engaged at Camp Uncas, Grandpa Morgan’s place in the Adirondacks, during a large house party. He and my grandmother were in England, and my mother and her older sister, Jane, had been left in the charge of a chaperone, whom they called “the dragoness” behind her back. There was a big storm and the house party was housebound. The rest is history.

The summer of his wedding my father was commissioned in the army as a lieutenant, and in April 1918, when my sister Virginia, whom we called Dina, was only a month old, he went to France with the American Expeditionary Forces commanded by General Pershing. Because he knew French he was saved from fighting in the trenches, and served as liaison to the French army. Forty years later, as his liner approached the French coast at the end of a transatlantic crossing, he recalled arriving in France in 1918:

I am writing in the bar and I can see France. Looks as good as when we made it on the S. S. Northern Pacific in 1918. [I] remember how good it was to get ashore and to march out to some Napoleonic barracks outside of Cherbourg. And I was able to get into town a few times and dig up a French teacher to give me French lessons. Paid dividends.… When the regiment (305th Field Artillery, Henry L. Stimson, C.O.) left for Bordeau I was left behind because of my allegedly exquisite French to find the lost regimental baggage which arrived in spite of me!

Paul and Frances Pennoyer at the army camp in Plattsburgh, New York, in 1917 before he went to France

Round Bush, with the terrace on the south side, the grape arbor, and the veranda at the end

After he returned the next May, my brother Paul was born in 1920; my sister Tracy in 1921; Kay and I in 1925; and Jessie, named for Grandmother Morgan, a year later.

Just before my father went off to war, Grandpa Morgan had commissioned the architectural firm of Goodwin, Bullard and Woolsey to build Round Bush, a picturesque English-style country house of brick, stucco, and slate. The house featured at least twenty-three rooms, in addition to a seven-car garage, six-stall stable, pig sty, chicken pen, tennis court, squash court, and fifty-foot swimming pool. It sat on a hill overlooking more than fifty acres of fields, woods, and pasture. There were abundant flower gardens and several acres of vegetable gardens. It was named Round Bush after a hamlet near my grandfather’s estate north of London, Wall Hall, where my mother grew up, and had a perfectly round English boxwood bush at the center of the circular drive near the front entrance.

Inside, the house was conservatively and comfortably furnished. But dark, owing to a preponderance of gloomy wood; there was a living room, called the Oak Room, and the Pine Room, my mother’s study. There was also a light-filled terrace under a grape arbor off the dining room called the Blue Place, after the color of its flagstone, where we ate meals in spring and summer.

In the early years Round Bush was staffed, if on a reduced scale, like an English country house. There was a cook, Marie; an upstairs maid, Celia; two kitchen maids; an English butler, Blundell; a houseman, Bryce McNaughton, who did everything from making ice cream to shoveling coal, winding the clocks, and doubling as my father’s valet; a Scottish grounds superintendent, Alexander Banks, who lived in the gate house; two Sicilian gardeners, Louis and his cousin Sal (the latter, who endeared himself to all us children by furnishing us with forbidden chewing gum, died not all that long ago, at the age of ninety-five, having spent more than sixty years tending the Round Bush gardens); a French groom, M. de la Flèche, who lived in the stable; and a French governess for the three older children, Mlle. Mila. Then there was Nanny, Mary Leavey, a gentle Irishwoman who took care of us all through our nursery years and then stayed on through the decades to help my sisters with their young ones.

The Oak Room at Round Bush

The servants ate their meals in the servants’ dining room off the kitchen, but as in any English household Nanny ranked above them and was served her meals in her room next to the nursery on the second floor. After our supper in the nursery Nanny would take Kay, Jessie, and me into her room where we would gather around her Zenith radio at seven-thirty to listen to the nightly broadcast of The Lone Ranger, one of the most popular radio broadcasts in the 1930s. Each episode was introduced by the announcer with these words: “In the early days of the western United States, a masked man and an Indian rode the plains, searching for truth and justice. Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear, when from out of the past come the thundering hoofbeats of the great horse Silver! The Lone Ranger rides again!” The program always ended with the Lone Ranger catching the bad guys and riding off into the sunset shouting, “High-ho Silver, away!” to the sound of galloping hooves and Rossini’s William Tell Overture, even now inseparably associated with the series.

Robert M. Pennoyer, age eight, 1933

Nanny died in the mid-1950s when I was in Washington with the Office of the Secretary of Defense. I flew up to New York and went straight to one of those vast cemeteries in Brooklyn to be present with others from my family at her burial. I wept unashamedly.

Round Bush, the east wing

There were two chauffeurs (what with us six children and all the different places we always needed to be taken), Wilson and Buchanan. Wilson was of English stock, and Buchanan, who lived in an apartment over the garage, was Scottish. For all this, my mother liked to drive herself. She picked my father up at the station every weekday, and ferried all six of us to Green Vale School. Paul insisted on being left at the school gate to avoid being seen arriving with a gaggle of girls. “I felt that it was a very natural expression of his independence and didn’t blame him,” my mother told me.

My father got a kick out of cars and loved selecting them. I remember, in no particular order, a seven-passenger Buick roadster, a two-door Chrysler Coupe, a Plymouth station wagon, a wooden-bodied Ford wagon, a Brewster convertible, a Model A Ford, and a Packard. In the mid-1930s Pattison, one of Grandpa Morgan’s chauffeurs who had left his employ to open a Cadillac dealership in Glen Cove, brought a deluxe new four-door convertible to Round Bush so Dad could take it out for a spin. With me in the back seat and Pattison beside him, he sped over the roller-coaster bumps on Hegeman’s Lane to test the springs and shock absorbers.

Aerial view of Round Bush, 1935, showing the pasture below the house, the gatehouse, the vegetable garden, and the open country across Duck Pond Road

Each time Dad bought a new car he had a metal ornament he’d commissioned, a small cast of a skier in a crouching position, welded to the top of the hood. He liked gadgets and, before cars had taillights to signal turns, had an arm about ten inches long, with a red light inside, fastened to the doorpost on each side of the car between the front and back seats: when one turned the switch on the steering column, the signal arm would open horizontally.

Round Bush had a night watchman who patrolled the halls at night with his flashlight, punching his time clock with the keys affixed to the walls as he made his rounds. All would be quiet until at the crack of dawn several times a year I woke to a bloodcurdling scream when, at the sty behind the stable at the bottom of the hill, Sal and Louis slit the throat of some unfortunate pig so that our family could have homegrown bacon.

The Lindbergh kidnapping had taken place when I was six, and people with “names” felt vulnerable. At Green Vale, Gloria Vanderbilt was delivered each morning in a Rolls-Royce, with a guard riding shotgun up front, that stayed parked all day at the school entrance. (For what it is worth, I was an officer of the Dragoon Guards and she was in the chorus of rapturous maidens in a school Gilbert and Sullivan production.)

For several years we had a daytime watchman, an ex-marine named Wright. One afternoon in 1933 when I was eight, while playing in my sandbox, he told me how he had participated in the invasion of Nicaragua in the 1920s and discovered, and helped himself to, a chest of rare coins. He pulled a large 1808 Napoleon silver coin out of his pocket and gave it to me. Years later when I went to the Pacific, I took it with me as my lucky piece.

My upbringing could fairly be described as idyllic. My twin, Kay, and I and our younger sister, Jessie, ate all our meals in the nursery until we were judged mature enough to join our older brother and sisters at the dining room table. Our days were highly structured, with times set aside for play, naps, and being read out loud to from such staple fare as the Peter Rabbit books, Christopher Robin, Thornton Burgess, and The Wind in the Willows. Every New Year’s Eve, at seven o’clock—midnight in far-off London—we children were brought down to the Oak Room to listen to Big Ben ring in the New Year.

RMP’s sixth-grade report card at Green Vale, 1936–1937, showing his mother’s initials on each week

Before taking us to church on Sunday, our mother would make us recite our catechism from the prayer book, after which she would cut our fingernails. One Sunday, when our family pew must have been filled, Dina and I sat down on either side of Grandpa Morgan. My sister accidentally sat on his hat and spent the whole sermon trying to put it back into shape. She had exactly twelve minutes in which to accomplish this, for Grandpa had decreed that no sermon in his church should exceed that limit, and he was never without his pocket watch.

Frances Tracy Pennoyer with her children, 1929

Kay and Jessie were my stalwarts outdoors as well as in. We had two donkeys, Concertina and Clarinet, that we hitched to a wagon, and rabbits that we kept in a pen at the edge of the field. We had black Labradors that Dad delighted in teaching tricks. He would put a biscuit on their nose and make them wait until, on a signal from him, they would snap open their mouths. This would cause the biscuit to take off, and they would catch it on the way down.

We had an adorable old horse, put out to pasture in the field below the house: Marengo, named by my father for the Napoleonic battle. Whenever the local hunt, the Meadowbrook, came galloping by his fenced-in pasture Marengo, all fired up, would dash along inside the fence, kicking up his twenty-two-year-old heels.

We amused ourselves by organizing an event that we grandly billed as a circus. We prevailed upon our mother’s secretary to type up little programs, and made the household staff sit on the hill and watch us parade by with our donkeys and our wagon and our horse, charging them ten cents each. (We asked our mother to give the proceeds to the Seeing Eye.) You could do anything with Marengo (nicknamed “Silver” after the Lone Ranger’s horse): we lay on his back, stood on him, tweaked his vestigial mane and tail. “The Big Show” program for one September Saturday in 1935 consisted of a “Parade of Horses,” “Clown and Dog Tricks,” “Other Tricks,” “Trick and Fancy Riding,” “Indians,” “Playing Dead,” “Donkey Cart Rides,” and “Jumping,” with Kay and Jessie on Silver, and “High Bareback Jumping,” with just Jessie. I am listed as “Manager.”

Recently I discovered, pasted into one of the albums that my mother kept for seventy years, a letter to her and my father from the son of the superintendent, who was my age and grew up with his parents in the gatehouse at the end of our driveway. They were a vital part of our life at Round Bush. His letter, written on the occasion of his father’s death, gives a vivid account of his years in our midst, embellishing my own recollections of the simple pleasures of childhood in that earlier time.

May 28, 1966

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Pennoyer:

I can’t begin to thank you both enough for all you have done for me. You have been so wonderful during this most difficult of times that any words of thanks seem so inadequate. However, please accept my heartfelt gratitude for considerations and kindnesses too numerous to recount.

I cannot yet quite believe that my father and mother are both gone from this earth, yet reality is something that must be faced, and as time goes on I will realize that it is true.

Every time that I returned to Round Bush these last few weeks, there was something that brought to mind an occurrence or situation of my growing-up years there.

My earliest recollection is of Harold meeting us at the train. And then our first sight of the house, and how awestruck I was by its size. I remember the funny old stove in the kitchen with all its metal swirls and curlicues. Then the stable and the horses, the big field and the gardens, the pool and tennis court, and how gigantic everything seemed to me at age four.

Then, too, I remember the first time I met you, Mrs. Pennoyer. I stopped you on the back drive and said, “You should sound your horn like the sign said.” My first memory of you, Mr. Pennoyer, was seeing you on horseback going across the road. Then I remember the fun we had on Paul’s wooden railroad. Whizzing down from the big house to the playhouse, and Paul’s “bosun’s chair” on pulleys and ropes.

Then there were the cars. The old Brewster and what a thrill it was when Mr. Wilson took us down to Glen Cove with the top down. The wooden-bodied station wagon, Andy’s Model A Ford, the Chevy trucks, old and new—Dad’s 1930 Chevy. The old touring car and how big it looked. How spotless Andy and Mr. Wilson kept the cars and the garage.

The men. Harold and his constant troubles; Sam Dione and his wicked, wicked ways; Rocco who was a little off; Louie walking up the drive with his vegetable basket on one arm, humming to himself and trailing clouds of blue smoke behind him from his pungent pipe. And good old Sal, still going strong, and after thirty years I began to understand what he was saying.

The horses and donkeys, and what fun it was when Prindier got hooked to the sleigh and we children hooked our sleds on behind and went zipping around the track. How grand it was when we hooked Concertina to the donkey cart and went up and down the drive. The jarring ride when we had Concertina and Clarinet both pulling. And how we used to hook one each to a toboggan and trail off through the woods in the snow.

Then there was the “Silver Donkey Society” which, I believe, Jessie organized. The meetings in Bobby’s room and how intently we would listen to The Lone Ranger on radio. The fascination of the miniature steam engines that he and I would run, and the wide-gauge electric trains on the schoolroom floor.

Then there were the circuses that we held in the big field and how Mr. Pennoyer would take movies of us. How we would all struggle aboard poor old Marengo and go jogging around the field. How Fanny used to bring ginger ale mixed with orange juice out to us on the “Blue Place,” and Mrs. Pennoyer would read stories to us on the veranda on Sunday afternoons. How sometimes on a rainy afternoon we would play “sardines” upstairs. How you ever put up with the noise I’ll never know.

I remember the Republican Women’s Federation Teas and the time in 1936 when the donkeys brayed loudly as the good ladies left—giving a good laugh to all.

Then there were the parties and weddings—great events and wonderful to remember. Miss Virginia’s coming-out party and how beautiful everything looked. The big green-and-white tent on the lawn. The gardenias in the reflecting pool. The white rope and stanchions around the big swimming pool. The music, Champagne, and ladies in lovely gowns. All the cars in the big field and the lights all around. Then how the fierce storm broke, how soaked everyone was, and I remember how all the dye ran out of Dad’s tie onto his shirt. Then the next morning, getting up real early and seeing that one, lone, forlorn-looking car in the field that was full the night before. Funny the things that stick in one’s mind.

Then Miss Tracy’s wedding at the big house and the first sip of Champagne I ever had. Then Miss Dina’s wedding and how wonderful everyone looked. Jessie and Kay’s coming-out parties. Bobby’s wedding over in New Jersey and how Paul and I put stones in his hub caps. Then Kay’s wedding, and Jessie’s, and how impressed I was with the ceremonies at St. John’s.

The first grandchildren. Tony and Polly, and how Joan would wheel them up and down the drive. Then, as they grew older, how they liked Dad’s “lever,” as they called his truck. Now they are all raising families of their own.

Mr. Morgan. What an impressive figure of a man he was. I recall his friendly wave as he drove in, always with the top down on his convertible, winter and summer, his hat set firmly on his head and his ever-present pipe with the cover on it.

The maids and cooks. Cecilia Smith, sedate and prim, and how we used to kid her and she would get all flustered. Anna the German cook. Her wonderful cookies and cakes were a delight. The giggly Irish girls from some time back and how thrilled they were when after one of them got married you left Champagne on ice for them.

Paul and Bobby in the Navy and how fine they looked in uniform when home on leave. Paul’s motorcycle that both he and Bobby rode.

Paul’s marriage and raising his family on the place. Now they have grown. It seems no time since they were little tots.

And Bryce! Always so full of fun. Always so willing to help—and able to do so many things. The time in Maine when we were on vacation together, the last day he caught a large bass and decided to bring it home for mounting. Of course that was 1942 and we had to go and return by bus. By the time we got as far as Boston, our newspaper-wrapped prize was somewhat fragrant. With a few quick words of Scottish dialogue, Bryce handed the fish to a colored porter in the bus station. Quickly striding away we looked back and saw him standing there open-mouthed. Never a dull moment with Bryce around, and he has a heart as big as he is himself.

Then we have had our sad times, too, at Round Bush. Andy Buchanan’s sudden death while on parade with his beloved British war veterans. Mr. Sheldon Pennoyer’s fatal accident in Spain, a great talent stopped before his time. Mr. Morgan, too. Then Kay’s tragic loss of a son so early in life.

Of course through all these memories of Round Bush run my love and admiration for Dad. His character and discipline. The pleasure he took in his work. I see him, and feel that I always will, walking resolutely up and down the drive, sowing seed in the garden, tieing up the sweet peas, pruning the fruit trees early in the season, bent over the frames in Spring, raising the burlap structure over the chrysanthemums in Fall. Having fun with the grandchildren, both his and yours.

Living as we did in this cloistered world, we were all but oblivious of the world beyond. I do remember that one morning when I was about six Nanny led me through the kitchen to the back entrance to see an organ-grinder with a capuchin monkey. He had just trudged up the length of our long driveway with his little pet, who was wearing a jaunty cap. The man cranked the organ and the creature did its little tricks, after which it held out its cap for coins. I was given a nickel to put in the cap. As a child I did not know that this was the middle of the Great Depression and that the poor man was just trying to eke out a living.

One scene still haunts me. When we drove from Round Bush to Manhattan in the early 1930s, before there were the highways, we would have to take Route 25A, and as we came up through the Meadowlands, for at least two miles we drove through a valley between two mountains of garbage about thirty to forty feet high on either side of the road. The smell was god-awful. This was where New York put its trash. From the car I could see the narrow tracks on which the garbage was pushed on carts to the top, where it would be dumped, and there were people up there scavenging for food. By the time we returned from Europe in 1939, the garbage mounds were gone. Robert Moses had cleaned up the Meadowlands to create the space for the 1939 World’s Fair.

Although my parents were well read and well informed, growing up I never heard a comment from either of them relating to books, music, art, or, with one notable exception, current events. In 1936 my father was heavily involved in raising money for the Republican presidential candidate, Alf Landon, who was running against FDR, and he had asked Dina, who was eighteen, to solicit modest contributions from her classmates. “Daddy,” she said one day at lunch, “I don’t really mind collecting money for Mr. Landon, but sometime could you tell me what is wrong with President Roosevelt?”

At that point my father uncharacteristically exploded: “We never discuss that!” My mother turned beet-red, and a deep silence ensued. But after the war began, I never heard him say a word against Roosevelt.

In time I began to realize that something was missing. We had been taught by example never to betray emotion, never to show affection. There was no touching or hugging in our family. Whenever we got what was called “out of hand,” our mother would remind us that children should be seen and not heard, and she would caution that no good ever came of “bear play.” A photograph of the six of us, taken in the early ’30s on the lawn at Round Bush shows us arranged by age from Dina, who was around sixteen, to Jessie, who was about seven. Instead of holding hands or putting an arm around a sibling’s shoulder, we are standing in a row, erect, arms at our sides, and with at least a foot of space between each of us. Our mother, expressionless, is standing behind. Years later it dawned on me how unnatural, and even comical, we looked.

My mother had a solid disposition: no ups, no downs. She expected people to do what they were told, as she had always done what she was told. As a child I learned early never to question her authority. Years later my wife Vicky accused me of being a “goody-goody.” Given my upbringing, I didn’t feel the need to make any apology.

I have nothing against self-control, mind you, it is an admirable quality. The last stanza of “America the Beautiful” admonishes us to “confirm thy soul in self-control, thy liberty in law!” But it seems, as I look back, that my mother practiced self-control to a self-punitive degree. I can’t help feeling that she would have enjoyed life even more if she had only been able to open up a little. Outwardly she seemed to have the same reaction to taking the dogs for a walk as to my coming home for a few days’ leave after months at sea during the war. But she did care. A friend who was with my sister Jessie at Vassar told me a few years ago that she remembered the day my mother called to ask Jessie to hurry home because I was coming.

Frances Tracy Pennoyer with her children, 1935

I now recognize that this seeming absence of emotion on her part must have stemmed from a resolve not to sentimentalize. It was simply a question of how she behaved (with perhaps excessive restraint) rather than of who she really was: a good person who never raised her voice in anger, never criticized another human being, and never took advantage of the homage that people paid her. With this belated realization, my love and my admiration for her have strengthened. When all is said and done, the sum of her virtues, not to mention the faults she lacked, set an example for her progeny, and evoked in her servants and in those of my contemporaries who knew her a reverence normally reserved for royalty.

She taught us all to be honest, to be modest, and to show respect for our elders and for servants. She was thrifty, and taught us to be thrifty. For household supplies she went to Macy’s. When packages arrived, she unwrapped them carefully to save the paper and string, which she stuffed into an embroidered satchel that hung in the Pine Room. On our eighth birthdays, she gave each of us a little black notebook in which to enter, on the left-hand page, the sum of our weekly allowance, which started at a dime, and, on the right, each expenditure. (This gave me the sense, which has never left me, that small things matter.) We wore hand-me-downs. At St. Paul’s I was poor at hockey, the school’s major winter sport, in part because I was told to use my brother’s skates which were two sizes too large; and later, when I needed skis at school in Switzerland, I was told to buy a secondhand pair.

My mother had conservative tastes. She favored muted colors and would not follow the fashions. She hung on to some dresses for years. She never wore high heels, wearing ground-hugger shoes even when she went out in the evening. Her long hair was tied in a bun at the back of her head. She kept her fingernails short and unpainted, and wore no makeup and little jewelry, but did wear some sweetsmelling perfume which left its trace when she came to the nursery to kiss us goodnight before going out to dinner.

The fall horse show at nearby Piping Rock Club was the social event of the season, where all the other women would show up in silk dresses, high heels, and furs. My mother only came when one of her children was riding, and then her disdain for putting on the dog would be on full display. She tried to avoid publicity, but at one event a photographer did manage to take a picture showing her in a cloth coat, wool hat, and ground-hugger shoes. When it hit the papers the next day—the October 13, 1933, edition of the New York American—her expression suggested that she must have been gritting her teeth. The accompanying article struck a critical chord:

If only Mrs. Pennoyer would follow the lead of Mrs. “Jock” Whitney and take the hint about her sartorial effects. “Liz” Whitney, only a few days after I commented on her apparent indifference to clothes and feminine finery, looked the very epitome of la mode when I saw her the other evening.

Press photograph at Piping Rock horse show in 1933, published with the caption “Mrs. Paul G. Pennoyer wearing the same wool coat she wore last year.”

Two years later it was the premier society columnist of the era, Cholly Knickerbocker, who dressed my mother down for dressing down:

When I encountered Mrs. Pennoyer, the former Frances T. Morgan, at one of those numerous outdoor events on Long Island the other afternoon, she was anything but fashionably attired. Her costume consisted of an old brown skirt and slip-on sweater and a brown felt hat that looked as if it had seen several seasons of good, hard wear. If only she would take more interest in things sartorial. She stopped to chat about dogs with Frederic Pitts Moore, as both had shown entries on Sunday at the Phipps place.

A year later, Knickerbocker was still at it, mocking her:

Mrs. Paul Pennoyer, whose daughter Virginia was showing, wore, unless my eyes deceived me, the same blue cheviot costume she had on at the same event last year—or could Frances have liked it so well, she had a duplicate made this year? Her daughter was garbed in riding clothes, which she wears so well.

Other reports were less harsh:

Mrs. P. successfully keeps out of the limelight but is doing a good job on six children.

One reporter actually gushed:

The Paul Pennoyers are pals with their youngsters and go with them to see all sorts of sports. The children are as lively as the Teddy Roosevelt youngsters used to be in the old days of Sagamore Hill.

My mother’s daily routine included many of the things one would expect: arranging the flowers brought in from the garden by Banks and writing out menus for the cook (she never learned how to prepare even the simplest meal, and I do not recall ever seeing her enter a kitchen). She had no sports, but loved cross-country walks, and in the ’30s, and again after the war, she took us beagling. In those years before the countryside was overrun with development we could range for miles through open fields and woods. I remember that it took a good deal of energy to chase the fifteen or twenty hounds as they raced across the undulating landscape, giving tongue.