Читать книгу High Treason and Low Comedy - Robert T. O’Keeffe - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1.

Introducing Egon Erwin Kisch,

the Raging Reporter

ОглавлениеEgon Erwin Kisch (1885–1948) became a professional journalist in 1906. During his first two decades as a writer he was well-known in Austria, Germany and Czechoslovakia. As his reputation spread throughout and beyond Europe during the interwar years, he acquired the sobriquet ‘the raging reporter’.1 The nickname stems from the critical success and large sales of his 1925 book, Der rasende Reporter, a collection of his reportage and other short pieces published in Berlin. In terms of ‘identity’ (using categorizations common to his own period) he was Jewish (by family religious affiliation, not ‘nationality’), a citizen of the Austrian half of the Dual Monarchy, a ‘real Praguer’, and a man who thought and wrote in German but had a good command of Czech. After World War I he was a citizen of the new Czechoslovakian First Republic. From 1921 on he lived in Berlin until his exile in 1933, moving first to Paris, then to Mexico City during World War II. He returned from exile to Prague in 1946, old, tired, and somewhat disillusioned, yet managed to revise earlier works and write new pieces up until the time of his death.

Kisch undertook long journeys abroad during the 1920s and 1930s to observe and investigate contemporary political events and their historical and cultural milieus, which he reported on in a series of thematic books.2 These travels included trips to France, England, Spain, Russia, the USA, North Africa, China, Japan, Ceylon, and Australia. As a man he was gregarious, ebullient, and broadly curious about the world he lived in. As a journalist he was an inventive stylist. He was also active in left-wing political movements after 1918 (his communist affiliations will be discussed below). Most importantly, he was a prolific writer of both short and long nonfiction works, most of which are deemed to be ‘reportage’ by later critics and students of his oeuvre (the pigeon-holing of his writing into this elastic genre is somewhat misleading). At the age of 29 he wrote a novel that was well-received, and during the first half of the 1920s he developed an ancillary career as a playwright, a phase of his life and work that will be examined in detail for the first time in English in the present book.

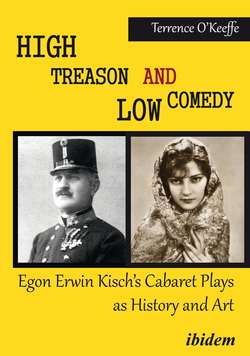

Translations of Kisch’s two most successful works for the stage are in Chapters 3 and 5 below. The first of the plays is a historical melodrama that deals with the last day on earth of an infamous, high-ranking Austro-Hungarian traitor, Colonel Alfred Redl, whose story played an important role in Kisch’s career as a journalist. The second play is entirely different in origins and atmosphere. It is the story of ‘Toni Gallows’, a rowdy Prague prostitute whose earthly travails unfold in slang as she tries to argue her way into heaven; here Kisch turned a short feuilleton into a cabaret fantasy-comedy with a strong streak of pathos. These two plays are treated in the present book as portals into a wider world. Inclusion of the translated plays is a necessary basis for discussions placing them in several overlapping contexts: biographical, historical, and cultural. Each of these plays enjoyed a long afterlife in several different media. Chapters 9 and 10 examine these various adaptations in the context of what happens when artists (including Kisch himself) transform history into art. Treating them in both intensive and expansive fashion allows discussion of the plays to ramify out in space and time, and takes the reader down informative and eventful pathways through history. But before reading the plays and the commentaries on them, the reader should learn more about their author and his career.

The English-language reader has three available sources of information about Kisch and his writing. First there is a fair sampling of his work in English translation: five of his books and a smattering of his magazine articles were translated into English during his lifetime. This sample is not fully representative of his interests or his approach to writing. Second is a 1997 “Bio–Anthology” written and edited by Harold Segel, an American scholar whose concise critical biography of Kisch is followed by his translations of 26 of Kisch’s outstanding pieces. (In German there are at least three major biographies of Kisch, several minor ones, and two ‘illustrated miscellanies’.) And, third, there are reviews of Kisch’s translated books and articles that critically analyze his work. This last body of writing in English is small, a mere trickle in comparison to the large number of such pieces about Kisch in German. In terms of significance, however, an exception to this is Scott Spector’s book (Prague Territories) about the unique ‘identity problems’ of German-Jewish writers in Prague during the years between ca. 1890 and 1920. Spector presents an in-depth analysis of Kisch’s chosen path (journalism and the evolution of his politics from typical German liberalism to secular-socialist activism) as exemplary of one of a complex of ideological and practical choices open to him and his Jewish peers in the ‘Prague circle’ in their attempts to reconcile the differences between Czechs and Germans.3 This will be discussed in more detail when dealing with Kisch’s ‘readership problems’ in Chapter 7 below.

During his lifetime Kisch had a presence in the English-speaking world that depended originally on newspaper and magazine publicity about his activities. In Europe his reputation as a journalist with a distinct voice and leftist perspective depended on his prolific writing of vivid newspaper and magazine articles and essays, often republished in book form as collections of reportage, and six or seven topical books based on his far-ranging travels. Between 1912 and 1948 twenty-four books by Kisch were published in German; this count does not include his juvenilia, co-written or co-edited works, pamphlet-sized publications, or several of his short plays. Many of his books were reissued during his lifetime, and equally many were translated into a variety of European languages (Czech, Polish, Romanian, Serbian, French, Dutch, Spanish, Russian, English, Swedish, and Italian).

Kisch is often credited with being the founder, foremost advocate, and best-known interwar practitioner of reportage, a form of journalism and essay-writing that will be discussed in more detail below. Posthumously his name and reputation have diminished outside the German-speaking lands, with the exception of the Czech Republic (and former Czechoslovakia), where he is one of the few ‘Prague Germans’ honored as ‘native sons and daughters’ of the city. In contrast to the normal fate of fading interest in all but the most famous men and women of any particular era, his name and writing are kept alive in recent German editions. In Germany (and, to a lesser extent, Austria) his status as the ‘master of reportage’ remains a subject of critical literary discourse. Film and television adaptations of his pieces continue to flourish.

In the English-speaking world Kisch has more or less fallen into oblivion since his death in 1948 (excepting Australia, for reasons explained below). Several of his pieces appeared in American magazines during the late 1920s and early 1930s,4 followed in the years 1935–1937 by English translations of three topical books that reported on his travels and direct observations. These were: Changing Asia (1935), Secret China (1935), and Australian Landfall (1937). Based on his 1931 travels through the peripheral Muslim lands of the USSR, Changing Asia conveyed a good deal of statistical (and bureaucratic) information and made the argument that ‘de–feudalization’ and vast improvements in the quality of life had been accomplished through Soviet economic programs; in addition to his political and social observations the book contains several colorful ‘adventure chapters’. The German title of the 1932 book, Asien gründlich verändert (Asia Fundamentally Changed) is more definitive of Kisch’s judgment that this modernization program had succeeded than the translated title used by his English publisher.

Secret China recorded Kisch’s illegal entry into the country and his travels between March and July, 1932, when he visited Shanghai, Peking, and Nanking. His trip took place at a time when a Japanese military incursion in Shanghai was in progress and when there was armed strife between Chiang Kai-Shek’s nationalist government, local warlords, and communist insurgents. In addition to his usual leftist-internationalist interpretation of these events (which led him to create an idealized picture of the Red Chinese enclave, based on the verbal reports of his contacts), Kisch wrote vivid chapters on Shanghai crime-lords and their corrupt police abettors and on his visit to an establishment housing retired Chinese Imperial harem officials, all of whom had been castrated. In comparison to the publisher’s translation, the German title of his 1933 China book captures the immediacy of his reporting on current affairs: Egon Erwin Kisch berichtet: China geheim (Egon Erwin Kisch Reports: Secret China).

This surge of translations of Kisch’s writing into English occurred toward the end of the period when his international renown peaked. His exploits in Australia in 1934–1935 also resulted in widespread publicity in the English-speaking world (and defamatory press coverage in Nazi Germany). Selected by Henri Barbusse, Kisch had gone there as the sole European delegate to a pacifist and anti-Fascist congress. Based on confidential intelligence reports from the UK, the Australian government had forbidden his entry. Attempting to bypass the ban, Kisch broke a leg when jumping from ship to dock in Melbourne. His legal case wound its way through the courts while he roamed the country on crutches, attending meetings and rallies as the government continued its efforts to deport him. Pro- and anti-government newspaper coverage of his case swelled into a floodtide of publicity.5 The trip yielded a book, Landung in Australien, published in Amsterdam in 1937. Its long opening chapter covered his political travails, with a good deal of facetious writing about the ineptitude of the government; it concluded with hortatory socialist rhetoric. Its second half comprised ten local color sketches about the history of the Australian labor movement and ‘exotic’ topics such as variants in the game of cricket and a famous horseracing murder case (of the horse, that is); it also included a rather misguided polemical chapter on “Lenin and Australia”. Noted above, its English translation, Australian Landfall, was published in London in the same year.

While both the original and the English translation of his book about his trip were banned in Australia between 1937 and 1969,6 Australians had a full report of his activities in their nation available in On the Pacific Front: The Adventures of Egon Kisch in Australia, a 1936 book written by one of their own, “Julian Smith”, the pen-name of a seasoned leftist journalist, Tom Fitzgerald.7 Smith recounted Kisch’s perambulations and painted a portrait of a witty, combative, risk-taking man whose character appealed to many Australians. His reportorial style was a direct tribute to Kisch’s, its author being an admirer and advocate of reportage as practiced by the master. Julie Wells has given readers an account and analysis of Kisch’s long-lasting influence on Australian journalism and liberal-leftist perspectives in the arts in general (e.g., he was a founding member of the Australian Writers’ League, which, though short-lived, had a significant local impact).8

Though the most widely publicized of Kisch’s long trips abroad, this was not his last. His on-the-scene reporting on the Spanish civil war was to follow, resulting in only one piece translated into English at the time, “The Three Cows”,9 while his other pieces about the war were published in German exile magazines and newsletters. Decades later they were gathered into a posthumous collection, Unter Spaniens Himmel (Under Spanish Skies), published in East Germany in 1961.10 His ten-month internment in New York in 1940 was followed by his 1940–1945 exile in Mexico, resulting in a book about historical matters and current life there, Entdeckungen in Mexiko (Mexican Discoveries). One of its reportages, “An Indian Village under the Star of David” has come over into English in two different translations, one as part of Tales from Seven Ghettos,11 the other in Segel’s Kisch Bio–Anthology.12 Both books are discussed in more detail below.

In late 1941 the English translation of his memoirs, Sensation Fair, came out ahead of the German version, Marktplatz der Sensationen, released in Mexico City in July, 1942.13 While the memoirs were critically praised in the US,14 they could only make a small impression, given the magnitude of recent events and the flood of reportorial and partisan writing about the unfolding of World War II. Their publication in New York coincided with the entry of the US into the Asian and European wars, the stalled German offensive on the outskirts of Moscow after six months of vast conquests in Russia, and a period of menacingly successful German U–boat activity in an attempted blockade of England. Sensation Fair recounts Kisch’s childhood and pre-World War I days as an enterprising reporter in Prague, with chapters that bring in events from his 1914–1918 life as a soldier and his 1920s research into the 1913 espionage case and major public scandal known as ‘the Redl affair’,15 which is the subject of one of the two plays presented below. Later additions to the memoirs during and after his lifetime are discussed in a Bibliographical Note that follows the main text of the present book. The memoirs present feuilletons, reportages, and articles that had appeared elsewhere in print as reminiscences, while also weaving essayistic connections between topics and between the different phases and perspectives of a long life as an adventurous and controversial professional journalist. Nowhere in Kisch’s memoirs does he mention that he had been a member of the Communist Party since 1919. His evasiveness on this point and what his Party membership meant for his writing will be discussed below.

The last of his books to come over into English was Tales from Seven Ghettos, a 1948 translation and augmentation of his 1934 book, Geschichten aus sieben Ghettos.16 The translator, Edith Bone, added chapters based on Kisch’s post-1934 writing about Jewish matters. Tales gives us the ruminations of Kisch, a thoroughly assimilated, non-practicing Jew, on Jewish lives and topics around the world in which he and they lived; it also includes essays about ‘exotic’ and legendary Jewish stories from across several centuries.

After Kisch’s death in 1948 there were no new translations of his work into English until 1997, when Harold Segel’s Egon Erwin Kisch, The Raging Reporter: A Bio-Anthology was published. Segel’s compact biography of Kisch also has translations of a wide variety of his reportages and essays, most of which had not been translated before. This yielded a virtual ‘sixth book’ of Kisch in English. Its concise bibliographical and critical discussions make it an ideal starting point for English-language readers to become acquainted with Kisch’s life and work, while its translations offer a wide sampling of his writing from over a period of four decades. Of relevance for the present book, Segel included a translation of Kisch’s small but influential 1924 book about the Redl espionage case.17 In the same year the most recent large-scale critical biography of Kisch in German was also published, Marcus Patka’s Egon Erwin Kisch: Stationen im Leben eines streitbaren Autors (Egon Erwin Kisch: Way-Stations in the Life of a Militant Writer). Patka’s exhaustive bibliography of writing by and about Kisch is the most comprehensive source of information for any and all research on the man, his works, and critical evaluation of his writing.18

Patka followed this in 1998 by compiling, editing, and contributing a summary critical essay to a profusely illustrated ‘Kisch biographical miscellany’, Der rasende Reporter Egon Erwin Kisch: Eine Biographie in Bildern (The Raging Reporter Egon Erwin Kisch: A Pictorial Biography). In addition to numerous quotations from Kisch’s works, including letters, the book contains reminiscences of friends, reviews of and commentary on Kisch’s writing by other writers and colleagues, and amusing anecdotes about the colorful, energetic, and congenial man himself. Illustrations are in the form of photographs (often of ‘Kisch among the famous’ of his era) and reproductions of sketches, finished drawings, paintings, postcards and posters that show Kisch in a variety of settings: his domiciles and favorite haunts in Prague, Berlin, Paris and elsewhere; meetings with colleagues and friends on political and informal occasions; and, important documents that chronicle aspects of his life. Patka’s essay, “Facetten rasender Zeit: Der Schriftsteller Egon Erwin Kisch hinter der Maske des Reporters”,19 was, in slightly edited form, translated as “The Writer behind the Reporter’s Mask” by Heidi Zogbaum. This is the Afterword to her informative 2004 book, Kisch in Australia: The Untold Story.20 Here Patka makes his case for Kisch as a “poet of everyday life”, also arguing that the Manichean polarities of Cold War-era opinion resulted in Kisch being arbitrarily and incorrectly dismissed as a merely “communist reporter” (or even a propagandist) in the West, including England and the US. The exception to this dismissal was continued and more nuanced interest in Kisch in both halves of the divided Germany. The present author believes that the available translations of Kisch in English support Patka’s contentions in this respect and give the reader an idea of his wide range of interests and his literary strengths (and occasional weaknesses as well).

Two more English translations of Kisch pieces came out in 2003 and 2015, respectively. The first was a chapter about “Fordism in Detroit” from Kisch’s 1929 book, Paradies Amerika (American Paradise), followed by Sheila Skaff’s analysis of Kisch’s rhetorical techniques, which show his literary gifts and convey his leftist political outlook on life.21 The full title of Kisch’s American travelogue is Egon Erwin Kisch Beehrt Sich Darzubieten: Paradies Amerika (Egon Erwin Kisch Has the Honor to Present You: American Paradise), showing his ironical attitude toward the ‘paradisical’ aspects of the USA. The second piece is “Elliptical Treadmill”, a vivid snapshot of the crowd at Berlin’s immensely popular six-day bicycle races, taken from 1925’s Der rasende Reporter.22 Graham Davis’s translation captures the excitement of Kisch’s sketch of the fervid atmosphere of a form of urban entertainment patronized by people from all walks of life, from prostitutes and gamblers to families with children, workingmen, and wealthy men-about-town, all in search of diversion through intoxication, sexual opportunities, and the thrill of thousands cheering on their favorites. Kisch’s gifts as a feuilletonist portraying a popular social phenomenon (with sociological implications) can be compared here with those of Joseph Roth, who covered the same event in his piece, “The Twelfth Berlin Six-Day Races”, available in a translation by Michael Hofmann.23

The preceding summary account of ‘Kisch in English’ takes the reader through representative Kisch pieces from the pre-World War I era (as recounted in his memoirs and stories in Tales from Seven Ghettos) up until the mid-1940s. Though amounting to about seven volumes of prose, it is small and somewhat selective in comparison to Kisch’s total output, at least half which deals with matters in Central Europe (if we extend that appellation to interwar Germany as well as to the successor states of the vanished Austro-Hungarian Empire). The English-language reader with some command of German has to go to linked compare-and-contrast books, like Paradies Amerika and Zaren, Popen, Bolschewiken (Czars, Priests, Bolsheviks) in order to get the full flavor of Kisch’s writing about contemporary social and political phenomena of intrinsic interest to Kisch’s wide readership during his heyday; or to books like Der rasende Reporter, with its 53 short, graphic pieces, to see why Germans and Austrians considered Kisch to be a master of Kleinkunst (“the small art form”)24 with a specifically modern cast.

As with all authors, it is necessary to take the facts of Kisch’s life into account when evaluating his writing―he lived in several cultural milieus that changed over time and had an impact on his responses to the world around him. Therefore a biographical sketch is given here.

Born in 1885 in Prague, Egon was the third of Hermann and Ernestine Kisch’s five sons. His family was middle-class and Jewish. His father owned a draper’s-clothier’s fabric shop, and many of his uncles and cousins were also small businessmen or professional men in Prague. Kisches, originally from the Eger (Pilsen) area of Bohemia, had lived in Prague for many generations and branched out into a variety of trades and professions, including medicine and law. Like the vast majority of Prague’s Jews, the family’s primary language and cultural affiliation was German, though Kisch himself was fluent in Czech and, in general, supported the aspirations of Czechs for more political autonomy within the Dual Monarchy. Eventually this turned into support for the new Czechoslovakian First Republic established as the Habsburg dynasty collapsed at the end of World War I and its holdings became reborn, new, or expanded nations.

Kisch attended the same Catholic elementary school (staffed by Piarists) where Franz Kafka, two years older, had been a student, followed by completion of the Staatsrealschule course of studies. Upon graduation he went to a technical school for journalism but did not complete the program. In 1904 he went through the one-year voluntary military program designed to advance its trainees to Second Lieutenant rank within the Austro-Hungarian reserve army. Having problems with discipline, he spent much of his time on guardhouse duty and finished the program as a corporal in the reserves, a status that would have an impact on his fate when World War I broke out. He was shifting about and dabbling with literature, having a volume of verse published in 1905; his always-supportive mother subsidized the publisher’s small edition. In the following year he had a collection of short stories published, Der freche Franz und andere Geschichten (Cheeky Frank and Other Stories). He later dismissed his poetry as sentimental juvenilia, while avoiding judgmental remarks on the quality of his stories.

In 1906 Kisch also began his career as a journalist, first interning for Prager Tagblatt, where his assignment was to attend the large number of public lectures on politics, science, and cultural topics given in Prague and then submit short, summary reports on them. After six weeks of this unsatisfying (and unpaid) employment he obtained a starting position with another Prague German-language newspaper, Bohemia, where he began as a daily-beat reporter covering fires, accidents, other mishaps, and any aspect of street-life that had ‘local-color’ value to the paper’s readers. He soon became a ‘specialist in crime’, reporting on Prague’s criminal underworld, police courts, associated seedy venues, and its demi-monde of prostitutes, pimps, and assorted low-level thugs who lived in the legal twilight zones common to all large cities. As he continued as a reporter he acquired editorial duties and wrote a Sunday feuilleton column, “Roaming through Prague”―he used the opportunity to live briefly with the homeless and to take a variety of proletarian jobs in order report on the abysmal living and working conditions of Prague’s large ‘underclass’, which had few tribunes speaking publicly on their behalf.25 Edited and rewritten material from his newspaper reports came out in book form as well, beginning with 1912’s Aus Prager Gassen und Nächten (From Prague’s Alleyways and Nights) and 1913’s Prager Kinder (Children of Prague—with “children” meaning the city’s native sons and daughters).

In his last two weeks at Bohemia Kisch was involved in breaking the story behind the suicide of Colonel Alfred Redl during the early morning hours of May 25th, 1913. Within two days of the event, Kisch, based on his journalistic experience and intuition, had acquired enough information from unnamed ‘inside sources’ to contradict the benign story put out by the General Staff of the Austro-Hungarian army that Redl had taken his own life because he was suffering from “insomnia and nervous exhaustion” related to his diligence in the performance of his military duties as the General Staff Chief of Prague’s VIIIth Army Corps. Redl, well known to the Viennese public, had spent most of the previous decade as the leading military intelligence expert within the General Staff’s Evidenzbüro, which managed both espionage and counterespionage matters. He proved to be the highest-ranking traitor within the army, having sold large amounts of sensitive military information to Russia and Italy for a decade or more. Kisch’s unsigned reports on the scandal led to a press, parliamentary, and dynastic furor directed at the General Staff and its Chief, Lieutenant Field Marshall Baron F. X. Conrad von Hötzendorf (usually referred to by historians as “Conrad”). The details of the scandal and how Kisch wrote about it in a 1924 book of investigative journalism will be discussed in Chapter 4 below, because portions of it are the basis of his 1920s play about Redl, Die Hetzjagd. Additionally, the book is illustrative of the theme of what happens to a narrative when historical material is used for subsequent transformations into works of art.

In mid-June, 1913, Kisch moved to Berlin in search of other writing opportunities and a broader reading public. During his year in Berlin he wrote a novel, Der Mädchenhirt (The Shepherd of Young Women, a colloquial expression for a pimp—in English the book is usually referred to as “The Pimp”). It drew upon his observations of Prague’s underworld during the preceding years and was hailed as a “return to naturalism”26 at a time when various forms of modernism, especially Expressionism, were ascendant (at least in critical opinion) in all of the arts.27 As some critics pointed out, the main virtue of Kisch’s novel, regardless of its position in the ongoing debates about appropriately ‘modern styles’ and about German vs. Czech strife in Prague, was its bringing to the attention of the public the pressing issue of social inequality as manifested through the struggles of ‘little people’ in the new urban jungles of the era.28 Spector noted that Kisch had craftily escaped the rhetoric of ‘biological’ and cultural arguments regarding ‘nature vs. nurture’ as the determinants of character and behavior (advanced by ‘race theorists’, including German nationalists). Instead Kisch redefined the Czech–German contest as part of the unfolding class conflict of modernity, in other words, as a type of raw power struggle in which ‘national character traits’ were irrelevant. In addition his protagonist, the illegitimate offspring of a sexual liaison between a German father and Czech mother, subverted the old Bohemian-German trope of masculine Aryans subduing and stewarding hyperemotional, culturally primitive, ‘feminine’ Czechs (who here represent Slavs in general, all in need of ‘good German management’).29 While writing his novel in Berlin Kisch patronized bohemian cafés and circles, looking for an entrée into writing for the stage. In June 1914 he was appointed Dramaturge of a small theater and troupe that presented ‘socially conscious’ plays (Sozietätsbühne). This prospective career came to a sudden halt with the outbreak of World War I―as a reservist in the VIIIth Army Corps, Kisch was summoned to Prague and activated as an infantryman with the rank of corporal.

Kisch served in the Austro-Hungarian army for the duration of the war. As a footslogging rifleman he participated in one of the war’s earliest battles, an offensive launched into a salient between the Sava and Drina Rivers in Serbia. His graphic description of this battle, in which the Austro-Hungarian army, a victim of its own haphazard planning and incompetent leadership, suffered large losses of men and equipment to withering Serbian machine- gun and artillery fire, was translated by Harold Segel as “Episodes from the Serbian Front”.30 The piece comes from Kisch’s war diary, which appeared in 1922 as Soldat im Prager Korps (A Soldier in the Prague Corps) and was reissued in edited and augmented form in 1930 as Schreib das auf, Kisch! (Write It Down, Kisch!). The diary was not published at the time of its creation on account of Austria’s strict censorship of any and all realistic reporting about the war (a policy most notably belittled by Karl Kraus in his ‘monster play’, Die letzte Tagen der Menschheit, or “Mankind’s Last Days”). A hundred years later the historian Max Hastings, in Catastrophe 1914, cited passages from Kisch’s diary in order to vivify his accounts of battles fought on the Serbian and Russian fronts.31 Kisch’s unit was transferred to participate in the grim 1914–1915 winter fighting along the line of the Carpathian mountains, where he was promoted to lieutenant, wounded by a grenade, and, after hospitalization, assigned to the army’s press corps. In this job he re-established contact with Franz Werfel and met Joseph Roth and Robert Musil, who was his editor for a while; he maintained contact with both of these colleagues and rivals over the decades.32

The loss of the war, the collapse of the Habsburg dynasty, and the rapid disintegration of Austria-Hungary in October, 1918, led Kisch into a new phase of life and a new set of political commitments. Like those of many soldiers on both sides of the conflict, his beliefs about society and politics had been radicalized by his experience of the war. During his last year of service he illegally attended various leftist conferences and ‘soldiers councils’ meetings. At the war’s end Kiich was on the scene in Vienna in uniform, becoming an agitator and leader of the Red Guard, a paramilitary force that threw its support to communists and other leftists in an abortive coup attempt against the conservative government of rump Austria.33 Soon thereafter he joined the Communist Party.34 Kisch remained evasive about his Party membership throughout his life. In situations that held the prospect of negative consequences (e.g., his status in Australia in 1934–1935 or in New York in 1939–1940), Kisch lied outright and denied any affiliation with the Communist Party.35 In contrast, Istvan Deak’s prosopography of Germany’s leftist, radical, and revolutionary intellectuals associated with the journal Die Weltbühne supplies a concise biography of Kisch that emphasizes his Party connections and various left-wing committees and organizations he either founded or belonged to.36

Kisch remained in Vienna throughout 1919, took part in the press wars between the left- and right-wing factions of Austrian political life, and experienced discouragement about the political situation and his diminishing opportunities to publish in Austria. He returned to Prague in 1920, worked for Prager Tagblatt, and re-established connections with his numerous friends and acquaintances who were active in both German and Czech literary and theatrical circles. He wrote Die Abenteuer in Prag (Prague Adventures) during 1920. It was a synthesis of reminiscences about his family and its history with colorful episodes recounting the city’s political and cultural life; it included versions of some of the work he had published in 1912 and 1913 and has been called by some “his first memoir”.

In 1921 he resettled in Berlin, which became his home base until his expulsion from Germany in 1933. Throughout the 1920s he traveled whenever necessary to Prague and Vienna in connection with his theatrical efforts and other publishing projects. In 1923 he compiled and edited an anthology of “classical journalism”. Kisch’s book about the Redl affair appeared in 1924. Though involved in theatrical projects during these years, he was obviously busy in writing to his main strength, reportage. In 1925 the book that spread his reputation as a master of reportage, Der rasende Reporter, sold well, was widely reviewed,37 and went into numerous reissues.38 Late in the same year he took his first trip to the Soviet Union, beginning his series of world-wide travels that resulted in thematic books of reportage.

Because Kisch and ‘reportage’ were almost synonymous for many of his readers, it is necessary to characterize this form of writing. What was it and what was it believed to be, especially with regard to Kisch’s career? The first hint can be seen in the materials that Kisch chose for his compilation Klassischer Journalismus, which gathered pieces by venerable ancestors of reportage as Kisch came to see it. Though many of the selected authors (e.g., Pliny, Luther, Napoleon, Bismarck) had not been journalists, he grouped them with writers from the late 18th century forward who had practiced journalism at one time or another in their lives, much of it adversarial. Vivid writing based on direct observation influenced his selections, so he was amenable to including short pieces by Viennese feuilletonists whose work he admired (e.g., Peter Altenberg). In his Introduction to the collection Kisch stated his belief that there was such a thing as totally objective or impartial journalism.39 Within a few years he was to change his mind about this, influenced by his leftist political beliefs and impressed by John Reed’s Ten Days That Shook the World, which gave an enthusiastic, approving portrait of the Bolshevik leadership in the USSR (he wrote an Introduction to a 1927 German translation of Reed’s book).40 In Kisch’s mind, reportage acquired a leftist political impetus and political goals, which, if skillfully woven into the narrative of a report, would persuade the reader that the implicit socio-political framework of his writing was the correct one.

Using Kisch’s own criteria for writing ‘legitimate reportage’, a working definition would include the following elements. It is fact-based reporting that also investigates deeper social and political causes behind the facts. It uses what Kisch called “logical fantasy”, which he defined as the most plausible and effective narrative means to connect and explain a series of related facts. It is open to literary devices such as metaphor, irony, sarcasm, taking an indirect path to a revelation, and fashioning an authorial narrative persona who observes and reports, but it should use everyday language and avoid literary flourishes based on purely aesthetic standards (‘art for art’s sake’). It is often impressionistic in its attempt to vividly re-create a situation or event, using fragments of reality in the manner of photographic montage. It is partial to a ‘you-are-there’ recounting of events, emphasizing the reporter’s direct observation and the human factor, i.e., how events affect the common man and woman as they perceive them. In the right hands (e.g., Kisch’s) it can be used to address historical topics as well as current events.

As to its political component, reportage is adversarial toward the conservative forces of society and those in power. It advances the causes of progressivism and improvements in the lives of workers and anyone else excluded from social and political influence. And, through militancy and exhortations, it aims to change society as well as to observe and describe it. Thus, Kisch’s 1935 piece, “Reportage als Kunstform und Kampfform” (“Reportage as Art-Form and Combat Style”) highlights militant advocacy as a basic component of reportage.41 In an analysis of Der rasende Reporter, Keith Williams noted that although the book’s Foreword hewed to the principle that the ideal journalist should be neutral, the actual writing implied just the opposite, i.e., there are no simple ’facts’ in economic and social life―the reader needs information about prevailing political structures and ideologies that underlie the facts in order to understand how and why they exist as they do. Williams calls the interlocked set of techniques Kisch used to indicate these underlying structures “defamiliarizing the familiar”. For Kisch this meant, as Williams puts it, “demystifying the alienated appearances sponsored by capitalism.”42

None of the foregoing constitutes a theory of reportage, but is rather a set of journalistic guidelines or standards. During the Weimar Republic years, when Kisch advocated this kind of writing, he was not alone in his turn away from the recent achievements and stylistic approaches of other forms of modernism (e.g., Symbolism, Expressionism, ‘stream of consciousness’ writing). In Weimar-era Germany the term die neue Sachlichkeit (“new objectivity” or “new matter-of-factness”) described the period’s turn toward more ‘factually engaged’ works in the realms of literature, painting, architecture, film, theater, and music. The extent of this stance can be seen in the subtitle of John Willett’s survey of Weimar-era art and politics, The New Sobriety 1917–1933, wherein “sobriety” is an alternate interpretation of Sachlichkeit. Willett writes that Kisch’s contemporaries saw him as an able representative of the era and its concerns, to the point that in their minds his name was synonymous with reportage, a form of writing they perceived as parallel to experimental ventures in film, drama, and the visual arts.43

The foregoing account of reportage’s ideal constituent elements can be challenged when considering any particular piece that claims to adhere to its standards. Political tendentiousness might undermine accuracy, and imputed motives and causes might be incorrect. Contextualizing one’s gathering of facts (‘raw data’) within a political-philosophical ideology, Marxism-Leninism, already points to ways in which the meaning of facts might be distorted, while inconvenient facts might be ignored. Needless to say, this applies to all ideological frameworks through which facts are selected and interpreted (e.g., reporting that assumes the ‘natural’ or ‘inevitable’ status of capitalism, as in our own time). In addition to these commonplace provisos about the nature of journalistic objectivity, Kisch’s desire to make his reporting interesting and entertaining points to other ways in which fictional devices (story arcs, clear contrasts between villains and heroes, the invented persona of an ‘objective narrator’, reconstructed dialogues, etc.) penetrate literary nonfiction. There are no firm criteria for deciding when the already vague boundary between objectivity and the reporter’s subjectivity drifts too far to the subjective or interpretive side. Another way to put this is that the boundary between fiction and nonfiction is often not clear. Whether Kisch pondered such matters in any depth is unknown.

In English-language writing the problem has reared its head several times in the recent past. Debates about the relative merits of tabloid journalism versus writing published by august newspapers with stricter fact-checking criteria have been running for more than a century. The American ‘New Journalism’ of the 1960s–1980s yielded extended interpretive reportages (by Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Jimmy Breslin, Janet Malcolm, Norman Mailer and others) and even ‘nonfiction novels’ (e.g., by Truman Capote and Mailer); these blurred previous journalistic boundaries. The advent of round-the-clock cable television news programs, internet news blogs and tendentious websites, including those that dispense ‘fake-news’, has exacerbated competing standards of ‘what is fit to print’. Were he alive today, Kisch might relish some of these contentious battles while being mystified or horrified by others.

During his pre-1914 years as a Prague journalist Kisch made no specific pleas for parties on the left. He was vaguely aligned with the old liberal Bohemian-German values that had been adopted by many of Prague’s Jewish families. After the war, when his political beliefs took a definite shape, he used wry suggestiveness rather than blatant didacticism to convey his ideology to the reader; occasionally he shifted into outright propaganda. He was, in principle, a communist, but he did not allow his topical interests or his writing style to be dictated by the rigid Party line. It seems that the cultural bureaucrats of the Party never attempted to force Kisch into this mold; perhaps, with his celebrity and his broad network of moderate, liberal, and non-communist leftist contacts, he was too valuable an asset to be bullied or tampered with. In the terminology of Russian and Comintern intelligence and Western counterintelligence he was an ‘agent of influence’, putting him on a plane with non-communist ‘fellow travelers’, though he was far better informed and more purposeful than they were. Whatever influence his communist affiliations had on his writing, Kisch wandered away from reportage with political implications whenever opportunities to do so occurred, indicating his broad, eclectic curiosity about human life. However, during the post-World War II years, Kisch’s East German biographers emphasized his credentials as a communist writer who often advanced the Party’s goals—at times this is a fair evaluation, but Kisch was much more (and perceived to be much more) than a writer who stuck to the Party line or had his writing pre-approved by Party officials.

An interesting light on Kisch’s status as an iconic socialist (or communist) journalist in post-1948 East Germany is shed by passages in Maxim Leo’s ‘family biography’, Red Love, published in translation in 2013 and critically discussed by the present author elsewhere.44 Leo remarked that his mother and her father (a well-known foreign-affairs journalist who served the DDR’s press agency, with intelligence duties as well) were admirers of Kisch. But they lamented the fact that they would never be allowed to write like Kisch, i.e., they could not apply their powers of observation and literary skills to an examination of the underlying power politics of the Soviet bloc and the grim realities of social and cultural life in the DDR. Like Kisch, they were uneasy about the trend of socialism in the Soviet world, but maintained a public silence. Here Kisch assumes the typical lineaments of an official icon honored in word, but not deed.

A glimpse into Kisch’s attitude toward the new communist state in the Soviet Union can be had by considering his trip there in 1925–1926. Michael Horowitz quoted a brief, starry–eyed letter that Kisch wrote to his mother soon after his arrival:

Dearest Mom―So I’ve been in Moscow and have been really lucky, for this city, both in appearance and in its inner essence, is the most beautiful in all the world. A thousand good wishes and kisses from yours, Egonek.45

Following up on this, Horowitz wrote that in his letters Kisch also noted the lack of housing, overcrowding in all public institutions, large numbers of homeless children living on the streets, decrepit public transport, and every other person appearing to be a newly minted bureaucrat. Here the reader sees enthusiasm, even awe, tempered by objectivity about persistent social and economic problems in the USSR. This objectivity was probably why Kisch’s book Zaren, Popen, Bolschewiken, the fruit of his observations during his first trip to Russia, was not translated into Russian, though earlier and later collections of his reportage were.

Both concise and more expansive definitions and discussions of reportage can be found in Kisch’s works,46 in the analyses by Kisch’s major East German biographers, Dieter Schlenstedt47 and Fritz Hofmann,48 in the 1997 biographies by Segel49 and Patka,50 in Spector’s parsing of Kisch’s reportage as a “cultural re-mapping of Prague”,51 in Peter Monteath’s article on Kisch’s Australian adventures52 and in pieces about Kisch written by his contemporary admirers53 and imitators.54 Looking at pitfalls inherent in accepting at face value an idealized form of reportage as presented by its practitioners and advocates, Peter Steiner undertook a critique of the most famous post-World War II piece of reportage, Julius Fučik’s Reportage: Notes from the Gallows, first published in Czech five years after Fučik was guillotined in 1943.55 Steiner’s analysis makes plain the book’s religious-mythical (‘Christological’) framing of the story of Fučik’s captivity and execution by the Nazis and how it became a propaganda tool of the Czech communist leadership during the post-war years (as it was caustically depicted in Milan Kundera’s novel, The Joke). In such a case of hortatory, partisan political writing it is difficult for an author to escape using the devices of fiction, sometimes drifting into poetic and rhetorically driven representation of crass realities, as Fučik often did.

In its glory years, when the claims of reportage were being advanced as an alternative to conventional journalism (‘just the facts’ articles and the printing of officially released information without challenge or comment), Kisch and others also argued for reportage’s superiority over fiction as a mirror of the world. They presumed it was the wave of the future, with literary fiction itself on the verge of death due to trends in current political and literary life; obviously this was a mistaken judgment. Reportage did not disappear with Kisch’s death in 1948. In the West the term denominates social and political reporting that exhibits the author’s literary skills and analyzes current events in terms of deeper, yet explicable causes that may not be immediately apparent to the reader; it often has an implicit political message. Large anthologies of reportage have been published in the US and Great Britain between the 1950s and the present, yet none of them includes articles by Kisch or even mentions him as a major, influential interwar practitioner of the form.56 As Patka surmised, this reluctance in the West to deal with Kisch as a master of reportage is an artifact of the fixed attitudes that accompanied Cold-War polarization of opinion. Kisch’s reputation in Germany and Austria, built almost entirely upon an assessment of him as the founder and cynosure of modern reportage, remains strong. However, in the US and the UK (but not Australia) he has gone missing from the genealogy of reportage in the minds of contemporary editors and compilers of anthologies.

While continuing to practice journalism in this mode, Kisch encountered major impediments in reaching his German-speaking readership after the Nazis ascended to power in early 1933. After the Reichstag fire he was rounded up as a target for internment by the new authorities; his account of his captivity has been translated by Harold Segel.57 The possession of a Czech passport facilitated his release from jail, but from March, 1933, until the end of the Second World War his books were banned (and burned) in Germany. Kisch made Paris his next home base, soon moving to the town of Versailles, where, in 1938, he married his secretary of many years, Gisela Lyner (he had a reputation as a ‘charmer’ and womanizer in his earlier years). During his exile from Germany his new volumes of reportage, numerous newspaper articles, and reports of his anti-Nazi and anti-Fascist activities could only reach a vastly reduced audience of German readers, i.e., fellow-exiles and emigrants from Germany predisposed to sharing his ideas and ideals.

Kisch’s travels continued—England, Australia, Spain during its civil war—as did translations of his work, but the growing tide of partisan journalism associated with political turbulence and the likelihood of a major war tended to drown out his voice. This was especially true in the English-speaking lands, which had their own prominent overseas journalists, for instance Hemingway, Orwell, and John Gunther; the first two of these were ‘literary journalists’, while Gunther’s practice of writing countrywide socio-political surveys was similar to Kisch’s approach to international reportage. He stayed one step ahead of the Nazis, leaving France in 1939. Quarantined in New York for ten months, he was denied entry into the US on political grounds (as a known leftist and ‘trouble–maker’), resulting in his spending the World War II years in Mexico, where he completed two books discussed above.

It was in Mexico that the allegation that Kisch was a communist propagandist (or ‘Party hack’) received some ammunition. Kisch wrote a slanderous diatribe against Gustav Regler, an old colleague who had left the Party and denounced the sins and crimes of Stalin and his abettors. Regler, to use the stilted jargon of the era, was now accused by pro-Russian intellectuals and writers of being ‘objectively Fascist’, because he did not give the USSR carte-blanche in its internal political life or manipulative machinations abroad (he was also accused of collaboration with the Vichy authorities). Kisch praised Stalin’s 1937–1938 lethal purge of military men on trumped-up charges as necessary and useful in bolstering the USSR’s military capacity—a nonsensical and factually false interpretation of events that also ignored the inconvenient fact that the Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939 had facilitated Nazi aggression. The offending article was published in the New Masses in March, 1942 and became the focus of an ongoing war of words between Party hard-liners and the non-communist, anti-Stalinist left in the US.58 This unseemly controversy and the political and personal reasons behind Kisch’s behavior in the case have been analyzed and interpreted by Patka,59 Heidi Zogbaum,60 and Jonathan Miles, Otto Katz’s biographer.61 Zogbaum remarked that Kisch’s writing about Regler may have been motivated by his desire to protect Katz (a well-known organizer who used the alias André Simone) from expulsion from Mexico, while his collapse into mendacity and implausible reverence for Stalin was probably motivated by uncertainty over his own prospective post-war status and livelihood. Separation from the Party at this point in his life would have meant social isolation and anxiety about what would happen to him and his wife in the near future. His role in the affair did, in fact, isolate him from a variety of American liberals and leftists who had previously admired him.

In April 1945, during the final weeks of the war in Europe, Kisch celebrated his 60th birthday in Mexico City. The festivities put together by the exile community went on for a week, and there were gifts and tributes to him from abroad as well.62 Of relevance to the present work it is notable that his friends put on a revival of his play about Colonel Redl as part of the celebrations.63 Rather than nostalgia or recognition of how the case had contributed to the demise of the Old Regime, perhaps what they were marking with this choice was the fact that Kisch’s reporting on the case had spread his reputation as a tenacious investigative reporter. The specific controversies of the late Habsburg world were now, or seemed to be, in the distant past, given the events of 1933–1945.64 This distancing was the product of an optical illusion, although it was not clear at the time. These old (pre-1914) controversies have not yet totally subsided, as can be seen in the rampant chauvinism, irredentism, and anti-Semitism within Central and Eastern Europe in the present day. Four decades of Moscow-enforced ‘fraternal socialism’ in the Soviet bloc of satellite states collapsed into civil wars and ethnic-supremacy campaigns after the dissolution of the bloc in 1989–1992.65 Once again nationalist autocrats (‘strongmen’) of the 1930s ilk66 accrued power in the region.67 The interwar strongmen were an outgrowth of widespread economic problems and nationalistic dissatisfaction with the peace treaties of 1918–1920. Today’s strongmen also reflect economic and ethnic dissatisfactions brought into the open by the collapse of communism, the social inequities and environmental damage caused by a form of global capitalism that seems beyond local political control, and perceived impingements on national sovereignty (and ‘national culture’) by the European Union.

In 1946 Kisch returned to Prague, where he was one of the few ‘Prague Germans’ allowed to resettle in Czechoslovakia (in 1945–1946 a thorough and often violent expulsion of approximately three million Germans from the reconstituted Czechoslovakia took place). His health was not good, putting an end to his days a roving reporter, though he wrote fresh pieces and revised older works. Kisch returned to a city that no longer had a vibrant, multicultural life, and he felt isolated and depressed on account of the death of family members and friends in the Holocaust. As Erhard Schütz wrote in an essay in the literary journal Text + Kritik, Kisch’s misgivings about how communism had developed in the USSR, his distress about the systematic anti-Germanism of the Czechoslovakian state, and a growing emotional bond with his fellow Jews characterized his postwar years in Prague.68 A series of strokes culminated in his death in March 1948, soon after the take-over of Czechoslovakia by a communist coup that had a high level of popular support. As some of his biographers and commentators point out, had Kisch survived until the time of the hysterical, anti-Semitic Slánský show-trial in 1952, it is probable that he would have been among the indicted.69 Given his broad web of non-communist contacts in the West, charges of ‘cosmopolitanism’ and espionage could have been levied against him. In fact, the all-purpose ‘Trotskyite’ slur was aimed at him even after his death.70 Like his old friend Katz (André Simone) he might have gone to the gallows.71 He was fortunate to die when he did, spared a final disillusionment with the Communist Party, about whose crimes of commission and failures to establish a better society he had maintained a public silence, though he seemed to harbor many private doubts about the trend of events.

The foregoing Introduction addresses the matter of ‘Kisch in English translation’ and, in abbreviated fashion, several aspects of his life and work: his long career as a journalist; his travels and adventures, which resulted in thematic books; his ventures into fiction, including writing for the stage; his reputation during the interwar years as ‘the master of reportage’; and the relationship between his writing and his political beliefs and commitments. With regard to the topic of Kisch in English, I note that my translation of the two cabaret plays is the first instance of any complete fictional work of Kisch—short stories, a novel, and plays —coming over into English; only a few small illustrative excerpts of these works have been translated to date.72 It is my hope that this will contribute to a re-evaluation of Kisch as a more well-rounded and gifted writer, rather than as just a master of politically-framed journalism (a characterization that ignores his gifts as a feuilleton-writer and essayist).

The two plays selected were Kisch’s most successful works for the stage. As to the Redl story, a combination of materials from his 1924 book and his Redl play was adapted into a 1931 film that gave Kisch writing credits. In the previous year the story of ‘Toni Gallows’ that Kisch had presented in feuilletons and three versions for the stage was also made into a successful film. These adaptations indicated that producers and directors believed that both stories had popular appeal. Other stage, film, and literary adaptations of the Redl srory appeared in the 1920s, 1950s, 1960s and 1980s. Along with the later television-plays of the Toni Gallows tale, these constitute the ‘long afterlives’ of the stories that are discussed in detail in Chapters 9 and 10.

To reiterate, the play about Colonel Redl is a historical melodrama with comedic interludes (Kisch called it a “Tragicomedy of the General Staff”). It derives its narrative materials from a successful book of investigative—and, at times speculative—reporting about the famous espionage affair. The shorter play about Toni Gallows, a pathetic yet defiant Prague prostitute who argues her way into heaven, is based on a feuilleton-style newspaper sketch that was framed as a posthumous fantasy. Though the character of Toni is a fictional embellishment of a woman allegedly known to Kisch from his days as a reporter in pre-1914 Prague, the social milieu she dwelled in was real enough. The plays bring to light fictional techniques that Kisch sometimes used in nonfictional reportages and essays and thus contribute to an understanding of his approach to writing in general. They also raise more general questions about how historical events are transformed into works of art, a topic that will be addressed in the final chapter.