Читать книгу Albert Luthuli - Robert Trent Vinson - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Chief of the People

Since 1933, Groutville residents had lobbied Luthuli to stand for election as their chief and oust the unpopular Chief Josiah Mqwebu, who had replaced Martin Luthuli in 1921. Initially, Albert was very reluctant, for he loved teaching and a chief’s salary was only 20 percent of his Adams earnings. Some peers also rejected the notion that Luthuli, one of the very first African teachers at Adams, would abandon this high-status profession that ostensibly prepared young Africans for modern society to accept a putatively backward “traditional” chieftainship controlled and manipulated by the state.1 But by December 1935, he and Nokukhanya finally answered the call, believing that “the voice of the people comes from God.”

While rejoicing that they could now live together while raising their children, the couple knew that government chiefs like Luthuli were in a difficult, contradictory position, charged simultaneously with representing the interests of their people and administering unjust and unpopular government policies. Some chiefs used state backing to rule as tyrants while enriching themselves by laying claim to land, charging dubious fees, and accepting bribes for settling disputes. After winning Groutville’s democratic elections for the chieftainship in December 1935 and being installed as chief in January 1936, Chief Luthuli, though now earning considerably less money, scorned such extortionist measures—though his children periodically complained about their spartan lifestyle. Practicing Ubuntu, a concept that recognized the humanity and interdependence of all people, he governed with an inclusive democratic spirit, personal warmth, integrity, empathy, and judicious wisdom. Luthuli understood Zulu traditional governance as democratic, with chiefs legally bound to rule according to traditional customs, remaining responsive to the needs and desires of their people.

Though Groutville was a largely Christian community, Africans there respected the Zulu royal house, proclaiming, “Our doors face in the direction of Zululand!” Accordingly, Luthuli made obligatory visits to the Zulu royal capital in Ulundi, meeting with other chiefs and prominent elders and reveling in Zulu and court rituals that confirmed for him that he was no “Black Englishman,” since Zulu-ness was “in my blood.”2 His Congregationalist upbringing enhanced this democratic ethos as Luthuli worked with his induna—childhood friend and best man Robbins Guma—and a council of amakholwa (another term for converted Christians) and amabhinca (traditionalist) elders on judicial matters, reveling in the hard work of finding reconciliation and compromise with oppositional parties.3 He also included women, regarded as legal and social minors, in democratic consultations and facilitated their economic advancement by disregarding government prohibitions on their beer brewing and selling and their operation of unlicensed bars known as shebeens.4 Luthuli was a chief of and by, not above, his people, prominently leading the festive dancing and singing at community feasts. One community member remembered Luthuli as a “man of the people [who] had a very strong influence over the community. He was a people’s chief.”5

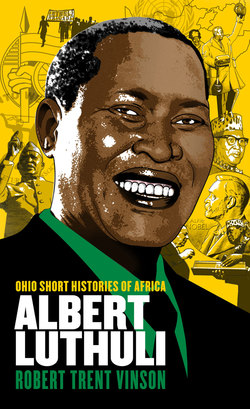

Congregationalist minister Posselt Gumede (left) and first ANC president John Dube (right) with Albert Luthuli (center) at Inanda Seminary, 1936. (Mwelela Cele, Campbell Collections of the University of KwaZulu-Natal)

Chief Luthuli nurtured the ideal of community to mitigate against the 1913 and 1936 Land Acts, which entrenched black dislocation and impoverishment. The Land Acts were part of the structural violence of segregation nationwide, further eviscerating African landownership and increasing grinding poverty in overcrowded reserves while forcing extensive labor migration to urban areas, which separated families and furthered social disintegration and dislocation. Luthuli later noted the disparity of whites claiming to need 375 acres per person to live comfortably while African families had only 6 acres, leading to soil exhaustion, lack of adequate grazing ground for cattle, and little heritable land for grown African children to economically sustain themselves and their families. He railed against the “land rehabilitation” schemes, which forced Africans to sell “surplus” cattle at reduced rates to white farmers who had comparatively plentiful land to absorb additional cattle and accrue more wealth. “Your solution is to take our cattle away today because you took our land yesterday,” Luthuli charged, telling unmoved state officials that cattle were cherished possessions and a meaningful source of wealth for Africans; forcing them to sell cattle represented a deep economic and psychic violence against his people.6 Particularly in Natal, the government’s 1936 Sugar Act, in attempting to keep sugar prices high by limiting production, disproportionately hurt African sugar-cane planters, who, in careful estimates Luthuli presented, lived substantially below the poverty line. Unlike white sugarcane farmers, African farmers held insufficient land, without legal title, and thus by law could not use their land as security on short-term loans to buy adequate machinery and fertilizer, thus offsetting the costs of planting, harvesting, and transporting sugar to the mills. As African migrant laborers left impoverished rural areas for work in the cities, some could not find work and became “redundant” urban workers, who then found themselves “deported” back to these same rural areas they had been forced to leave: a never-ending shuttle.

But state officials, including arrogant, culturally ignorant, and ineffective “agricultural demonstrators,” insisted that African poverty was due not to inadequate land but to supposedly inefficient African agricultural techniques. Luthuli’s chieftainship uniquely positioned him to observe the fallacy of state logic and the deepening poverty of the once-prosperous Groutville community and the tangible negative effects of African disfranchisement, onerous taxation without representation, land scarcity, and economic insecurity.7 He immediately revived the Groutville Bantu Cane Growers’ Association, a group of about two hundred small-scale cane growers (including himself) that successfully lobbied the millers to advance monies that would allow African farmers to meet upfront production costs. He also chaired the Natal and Zululand Bantu Cane Growers’ Association, bringing nearly all African sugarcane producers into one union. His tour of America in 1948 enabled him to procure a tractor that helped boost agricultural production by local farmers, some of whom thus increased their margins enough to educate their children.8 The African intellectual Jordan Ngubane, who studied at Adams when Luthuli taught there and later became Luthuli’s personal secretary and political ally, credited the chief with promoting economic development, increasing agricultural efficiency, sending more youth to schools and universities, and inspiring an optimism that belied the increasing hardships caused by government land policies.9

Into Politics

Luthuli joined the ANC in 1944, partially out of respect for the recently deceased Natal ANC president John Dube. ANC president Dr. Alfred Xuma had reinvigorated an organization virtually dead in the 1930s. He used his own resources to pay prior debts and finance new initiatives, established new branches, and facilitated the formation of the ANC Women’s League (1943) and the ANC Youth League (1944). Former Luthuli student Anton Lembede was the most influential Youth League leader. Before his untimely death in 1947, he influenced a young cadre of future national leaders including Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, A. P. Mda, and Oliver Tambo to adopt a more confrontational posture toward white supremacy. The Atlantic Charter, issued in August 1941 by U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston Churchill, defined British and American aims during World War II and their postwar aspirations. It declared, among other things, the right of all people to self-determination and the restoration of self-government. But Churchill and South African prime minister Jan Smuts claimed that self-determination applied only to countries occupied by fascist powers, not to European colonial possessions and South Africa. Thus, Luthuli and other Africans felt that support for Smuts’s South Africa in the wider war against Hitler’s Germany represented no more than a choice between white supremacist regimes, a “local master race versus the foreign one.”10 In 1943, accordingly, the ANC published African Claims, demanding for African self-determination, including a bill of rights, racial equality, universal suffrage, and nonracial citizenship for blacks in southern Africa.11

In 1946, Luthuli assumed councilor duties in the Native Representative Council (NRC), an advisory body to the government. Luthuli reiterated the demands made in African Claims and continued his longstanding complaints about inadequate African land, comments that enraged the white NRC chairman. With the support of other councilors, Luthuli protested the state’s use of coercive force to suppress a massive African mineworkers’ strike, condemning “the reactionary character of the Union Native Policy,” which exposed the “government’s post war continuation of a policy of fascism which is the antithesis of the letter and the spirit of the Atlantic Charter and the United Nations Charter.” The government, he continued, was “impenetrably deaf” to African groans of pain in response to oppressive segregationist measures.12 Luthuli would say later that the NRC was a “toy telephone” requiring him to “shout a little louder” to no one, and African councilors then adjourned in protest. The NRC never met again, and the government formally dissolved it in 1952.13

In 1947, Dr. Xuma and South African Indian Congress (SAIC) leaders Dr. Yusuf Dadoo and Dr. G. M. Naicker signed the “Doctors Pact,” pledging to fight together against South Africa’s racial policies, including at the newly founded United Nations (UN). Ironically, as Nazi-inspired apartheid leaders would soon rule South Africa, the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights exemplified an international human rights discourse that included racial equality, a partial reaction to the genocidal policies of Nazi Germany. Tellingly, South Africa abstained from the vote that approved the Human Rights Declaration. Gandhi, whose satyagraha campaigns while he was in South Africa between 1893 and 1914 set the course for his later successes in India, warned South Africa of its dangerous path: “the future is surely not with the so-called white races if they keep themselves in purdah. The attitude of unreason will mean a third war which sane people should avoid. Political cooperation among all the exploited races in South Africa can only result in mutual goodwill, if it is wisely directed and based on truth and non-violence.”14

The unexpected victory of the National Party in May 1948 made apartheid official state policy until 1994. Founded in 1933 by Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) minister and newspaper editor Daniel François Malan, the National Party was the political beneficiary of a resurgent Afrikaner ethno-nationalism that sought economic advancement, cultural autonomy, and explicit political measures to ensure Afrikaner power and identity to counter British political and economic dominance and African numerical superiority. Many pro-Nazi Afrikaners, including future apartheid prime ministers Johannes Strydom and John Vorster, had opposed South African military and economic contributions to the Allied cause against Hitler’s Germany, engaging in seditious activities that resulted in their detention during the war. As Africans and poor Afrikaners competed with each other for living space and jobs in a rapidly expanding manufacturing sector producing war materiel, Afrikaner nationalists complained of “swamping” by an African urban population that had doubled to 1.4 million in the interwar years. By 1946, there were 2.2 million urban-based Africans living in cities supposedly reserved for white permanent residence, and their growing militancy was exemplified in strikes, boycotts, and demands for better living and working conditions. Also, the close proximity of working-class Africans and Afrikaners renewed fears of racial mixing and prompted calls for policies that would ensure Afrikaner racial separation and preservation. Increasingly, Afrikaner intellectuals posited apartheid as a permanent solution for “the purity of our blood and . . . our unadulterated European racial survival.”15 The governing United Party of Prime Minister Jan Smuts, South Africa’s most prominent political figure, who also helped found the League of Nations and its successor the UN, had trounced the Nationalists in the previous 1943 election. In 1948, the United Party won the popular vote again, but because of greater electoral weight given to rural districts, which voted disproportionately for the Nationalists, and an alliance with a smaller Afrikaner-based Party, the Nationalists squeezed out an improbable victory. The surprised Malan, now faced with the unexpected task of converting apartheid from electoral slogan to concrete government policy, nevertheless hastened to hail the victory as divinely ordained.16

The Global Color Line

South Africa was part of the global hegemony of powerful white states and individuals exemplified by European colonialism in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean and continuing racial subordination in the United States. In June 1948, Luthuli traveled to the United States for seven months, during which he addressed churches, civic groups, youth groups, and others about the progress of Natal American Board missions, African rural development, and racial reconciliation.17 This was not his first overseas trip; in 1938, the chief had traveled to Madras, India, as part of an interracial Christian delegation to an international missionary conference. Despite the fact that South African segregation traveled outside its borders—white delegates traveled first class and the four Africans second class—Luthuli toured India and Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), met Indian, Japanese, Chinese, and African Christian leaders, and returned “with wider sympathies and wider horizons.”18 Luthuli’s tour of the United States took place during the 1948 presidential election, when President Harry Truman put forth a mild but virtually unprecedented civil rights agenda that sparked the “Dixiecrat” revolt of southern segregationists. Luthuli hoped that African Americans, who, unlike black South Africans, had constitutional rights, would ultimately triumph over Jim Crow practices and that the United States would be a positive model of multiracial democracy for his own country.

Suspecting that the South African government was monitoring him closely, Luthuli toured the South on Jim Crow trains to visit historically black universities—Howard, Atlanta, Tuskegee, and Virginia State—remarking, “I have such a great desire to visit my people in the South that I would have been awfully disappointed to return to Africa without doing so.” At Howard, Luthuli lectured on African history, met African students, marveled at the library’s vast book collection on Africa, and was hosted by members of Washington’s bustling, upwardly mobile black communities. During his lectures he explained enduring values of Zulu traditional society, Zulu religious concepts, and Zulus’ respect for law and order.19 In the wake of Gandhi’s assassination, Luthuli, who would later use Gandhian methods in the ANC’s antiapartheid campaigns, also lectured to the Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Society about Gandhi’s development of his nonviolent philosophy and strategy of satyagraha.20 While at Virginia State and Tuskegee, Luthuli visited black-owned and operated dairies, among other rural-based development and school projects. He discussed sustainable agricultural methods with successful black farmers and initiated conversations with rural parents and children about the quality of their education. His Virginia State host, Dr. Samuel Gandy, described Luthuli as “vigorous, hale and hearty . . . a living symbol of vitality” who was “easy to meet and know and brought no distinctions with him.” His visit sparked an “awakening on campus relative to Africa and an eagerness on the part of students to know more about this great continent.”21 At Tuskegee, Luthuli personally witnessed the industrial education model championed by the American-educated South African agricultural official C. T. Loram—a model that would be foundational to South Africa’s Bantu education system—concluding that the “manual crafts . . . do not seem to me to justify university degrees.”22

Albert Luthuli during his tour of the United States, 1948. (Luthuli Museum)

Jim Crow was ubiquitous. Howard, the mecca of black education and the educational pillar of an upwardly mobile black elite, was in the nation’s capital, the Jim Crow city of Washington, D.C. In Virginia, a restaurant did not allow Luthuli and Gandy to eat on the premises. Upon discovering Luthuli’s South African origins, the owner effectively declared Luthuli an “honorary white,” telling him he could stay, but not Gandy, whereupon the exasperated men left in disgust. Luthuli remarked that this southern tour had a profound effect on him, allowing him to “see South African issues more sharply, and in a different and larger perspective.”23 Luthuli’s American tour reminded him of the transnational nature of white supremacy: “those moments—a door closed in one’s face, a restaurant where a cup of coffee has been refused—that jolt the black man back to the realization that, almost everywhere he travels, race prejudice will not let him be at home in the world.”24 Luthuli heard stories from African Americans insulted by long-time prime minister Jan Smuts, who in 1929 had told American blacks that Africans “were the most patient of all animals, next to the ass.”25 Luthuli left America in February 1949 having felt the sting of American Jim Crow but also encouraged by African American progress against long odds.

When Luthuli returned to South Africa, the National Party, keenly aware that their slender electoral victory could be overturned in the next elections, was already moving to translate apartheid from a provocative electoral slogan into a comprehensive and ambitious social engineering political program that would ensure ethnic Afrikaner advancement and white racial supremacy. The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act (1949) and the Immorality Act (1950) outlawed marriage and sexual relations between whites and other racial groups. The Suppression of Communism Act (1950) stifled political dissent by defining communism broadly to include any resistance to the apartheid state. The Population Registration Act (1950) divided South Africa’s inhabitants into four racial groups, Africans, Coloureds, Asiatics, and Whites—and on this basis the National Party set out to create racially differentiated citizens and subjects in their “own” residential areas, with different employment, educational, political, economic, and social rights. The Group Areas Act (1950) extended government powers to create racially separate residential zones, including the forcible removal of people to create racially homogeneous areas. In Luthuli’s view, the apartheid regime and its white supporters had pirated the land, wealth, and government. More particularly, it had claimed ownership of the African majority, virtually enslaving them through apartheid laws. Africans were the “livestock which went with the estate, objects rather than subjects,” political footballs tossed about by the Nationalists and their white parliamentary rivals.26

At the December 1948 conference, ANC Youth Leaguers such as A. P. Mda, Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, and Oliver Tambo argued that the advent of the new apartheid regime forced the ANC to move beyond strictly constitutional methods. They proposed a Program of Action that would consist of civil disobedience tactics, including strikes and boycotts. Before the December 1949 ANC annual conference, they challenged Xuma to move beyond strictly constitutional measures to fight apartheid, but he refused to commit himself to the Program of Action. Inspired partially by Kwame Nkrumah’s direct-action anticolonial stance in the Gold Coast, the Youth Leaguers effectively seized power within the ANC at the 1949 conference, as delegates voted to adopt the Program of Action. Delegates also voted for the Youth League’s candidate for president-general, Dr. James Moroka, who defeated the chastened Xuma. Sisulu became ANC secretary-general, and six Youth Leaguers joined the National Executive.27

Luthuli would lead the execution of the Program of Action in Natal. Allison Wessels George (A. W. G.) Champion, who regarded the provincial Natal ANC as his personal fiefdom and felt no obligation to enact national ANC initiatives, also opposed the Program of Action. After initial reservations about African-Indian collaboration after the January 1949 Durban riots, in which some Africans, frustrated by the perceived arrogance and discrimination of Indians toward them, attacked Indians, Luthuli participated in joint-action campaigns with the Indian Congresses. This included a one-day strike on May 1, 1950, in which the South African police killed at least eighteen unarmed, nonviolent protesters, and a multiracial one-day stay at home on June 26, 1950, to protest the Group Areas Act and the Suppression of Communism Act. Luthuli resigned from Champion’s executive committee in protest of his dictatorial control of the Natal ANC, his opposition to the Program of Action, and his general resistance to national ANC centralization efforts.28 ANC leaders in Transvaal and Natal, particularly influential Youth League leaders M. B. Yengwa and Wilson Conco, and Jordan Ngubane, editor of the African newspaper Inkundla ya Bantu, persuaded Luthuli to stand as Natal ANC president at the 1951 Natal ANC conference.29 As Yengwa, who became Luthuli’s close ally as Natal ANC secretary and NEC member, noted, “Mr. Champion was not prepared to cooperate with the Indians, but . . . we argued that we have no alternative but to work with the Indians, that we are fighting the same enemy.”30 On May 3, 1951, Luthuli became Natal ANC president, defeating Champion in a contentious, raucous election. Though the embittered Champion became a longtime antagonist, Luthuli’s victory facilitated greater cooperation with the Transvaal-based national ANC and set the stage for Natal’s participation in the iconic Defiance Campaign.31