Читать книгу Albert Luthuli - Robert Trent Vinson - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

The Nonviolent, Multiracial Politics of Defiance

The Defiance Campaign

Luthuli became a national political figure during the iconic 1952 Defiance Campaign, a multiracial mobilization to resist apartheid led by the ANC, the SAIC, and the Coloured Peoples Convention (CPC). Luthuli led protests in Natal against the Pass Laws, Group Areas Act, the Separate Voters’ Representation Act, the Suppression of Communism Act, and the Bantu Authorities Act. The campaign modeled itself on Gandhi’s nonviolent civil disobedience strategy, which helped win India’s independence from Great Britain, and the mid-1940s Indian passive resistance campaigns against the so called Ghetto Act, which disenfranchised Indians and restricted their land ownership.1 Luthuli endorsed Gandhi’s satyagraha as an “active non-violence” that he felt had the power to change individual lives, mobilize the masses, and end apartheid. “We have declared to the world that we do not mean to use violence in furtherance of our cause. We will always follow the path of peace and nonviolence in our legitimate demands for freedom.”2 In April 1952, he gathered Natal ANC members to reaffirm their commitment to the Defiance Campaign, a pivotal moment that his close friend M. B. Yengwa remembered reflected his unprecedented willingness to defy government laws despite being a government-paid chief.3

Luthuli’s role as a staff officer was not to be arrested and go to jail, but to tour Natal to organize the campaign. With his rich baritone voice, he led crowds singing freedom songs. The Natal Campaign began in August 1952 as a joint ANC-SAIC endeavor, marking the first large-scale cooperation between Africans, Indians, and other racial groups in the province. Luthuli rallied thousands of people as Africans and Indians defied segregation practices in public facilities and Africans defied curfew laws in Durban.4 Over nine thousand people of all races went to jail for defying apartheid laws, and the prisons resounded with their freedom songs. The Defiance Campaign lived up to its name, but it was never going to bring the walls—or the laws—of apartheid tumbling down. Instead, the government used brute force to eliminate all “subversive” activity, soon to be defined yet more comprehensively.5 Nevertheless, the Defiance Campaign led to a dramatic increase in ANC membership (from an estimated twenty-five thousand in 1951 to one hundred thousand at the end of the campaign). It also facilitated the Congress Alliance, a broad antiapartheid front of independent multiracial, multi-ideological organizations that sought to end apartheid. If the Defiance Campaign did not end apartheid, it prepared its downfall by transforming the character and nature of the antiapartheid struggle.

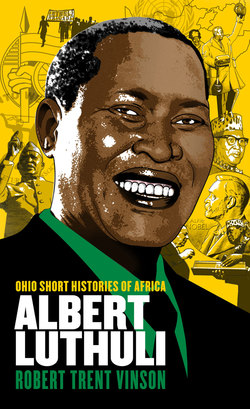

Luthuli signing up volunteers for the Defiance Campaign, 1952. (Luthuli Museum)

This was particularly significant in Natal, where memories of the Durban riots reinforced mutual suspicion and hostility between Indians and Africans. Even Gandhi had exhibited racial antagonism toward Africans, and his son, Manilal, who had remained in Natal, had previously referred to Africans’ “savage instinct” and doubted their ability to attain and maintain the spiritual and personal discipline to utilize satyagraha techniques.6 But Luthuli’s inclusive leadership style, open admiration for Gandhi’s satyagraha methods, and close relationships with Indian leaders, including Manilal, facilitated unprecedented levels of cooperation between Africans and Indians.7 Luthuli was a crucial influence on future Indian Congressites such as the antiapartheid activist Kader Asmal, who remembered, “I met him on a number of occasions in the late 1940s and early 1950s when he knocked on doors in my home town of Stanger looking for support. His non-racialism and his commitment to freedom and democracy made an indelible impression on me. Albert Luthuli was one of the most important influences leading me into the politics of liberation.”8 Luthuli’s multiracial stance allayed the suspicions of Indians and whites harbored by ANC activists like Dorothy Nyembe, who remembered how “Chief Luthuli taught us that every person born in this country had a right to stay and be free, whether he is Indian, African or white. We fought side by side.”9

From Government Chief to ANC President

By August 1952, government officials had concluded—not surprisingly—that Luthuli’s Defiance Campaign activity conflicted with his chiefly duties to administer and enforce government laws. Summoning Luthuli to Pretoria, Secretary of Native Affairs Dr. W. W. M. Eiselen ordered Luthuli to resign from either the ANC or the chieftaincy. When, after two months, Luthuli refused to choose, the government stripped him of his chieftainship, which included benefits such as paid school fees for his children. But Luthuli insisted, “a chief is primarily a servant of his people . . . not a local agent of the Government. . . . Why shouldn’t [Africans] assist this organization which fights for the welfare of the black man?”10 Luthuli lamented,

who will deny that thirty years of my life have been spent knocking in vain, patiently, moderately at a closed and barred door? What have been the fruits of my many years of moderation? . . .

. . . Has there been any reciprocal tolerance or moderation from the Government, be it Nationalist or United Party? No! No! On the contrary, the past 30 years have seen the greatest number of laws restricting our rights and progress until today, we have reached a stage where we have almost no rights at all: no adequate land for our occupation; our only asset, cattle, dwindling; no security of home ownership; no decent and remunerative employment; more restriction of freedom of movement by the pass laws, curfew regulations, influx control measures; in short we have witnessed in these years an intensification of our subjection to ensure and protect white supremacy.11

Luthuli fought apartheid on political and theological grounds, regarding Christianity as a stirring social gospel of justice, freedom, and equality and Jesus as the champion of the dispossessed who had died on the cross for all of humanity, not just whites. Luthuli argued that all Christians should fight for social justice, his politics reflecting his own understanding of Christianity: “I am in Congress precisely because I am a Christian. My Christian belief about human society must find expression here and now. . . . My own urge, because I am a Christian, is to get into the thick of the struggle with other Christians, taking my Christianity with me and praying that it may be used to influence for good the character of the resistance.”12 Thus, he criticized the many whites, especially within the Afrikaner Dutch Reformed Church (DRC), who used Christianity to justify white supremacy, relying on the Calvinist doctrine of an “elect” in claiming divine sanction to rule South Africa as a supreme and separate population over blacks.13 DRC religious leaders championed apartheid as a divinely ordained, comprehensive social engineering program that would create societal harmony through rigorous political, socioeconomic, and physical separation, thereby eliminating the supposed evils of racial egalitarianism.14 Despite the Christian principle of an “equality of believers” regardless of race, proapartheid self-professed “Christians” argued that in racial matters “all earthly distinctions remain.”15 For Luthuli, apartheid was a violation of God’s law, “contrary to the plan and purpose of God our Creator, who created all men equal.”16

At the ANC annual conference in December 1952, ANC delegates including Walter Sisulu, impressed by Luthuli’s “defiance of the government,” elected him president over Moroka, who had hired his own lawyer and disavowed Congress policies in court after being arrested for Defiance Campaign involvement.17 Taking the mantle of an organization that had just had fifty-two leaders banned, twenty leaders, including Moroka, and over eight thousand volunteers convicted for Defiance Campaign activities, Luthuli immediately visited national ANC branches countrywide. In the Eastern Cape’s Port Elizabeth, twenty-five thousand people came to hear him demand, “Vula Malan thina siya qonqotha” (Open the door, Malan, we are knocking!”), and sang, “Malan o tshohilole ‘muso oa hae. Luthuli phakisa onke’muso!” (Malan has taken fright, make haste, Luthuli, and form a new government!).18 At home, Nokukhanya vetted Albert’s speeches as they hosted visiting ANC members and friends such as Nelson Mandela, Mangosuthu Buthelezi, and other visitors, who, showing customary Zulu respect before entering someone’s home, addressed Luthuli by his clan name: “O! Madlanduna, Mashisha Sikhulekile Ekhaya.”19

The Violence of the Apartheid State

In response to the Defiance Campaign, apartheid South Africa evolved further toward a police state, with bans that forced Eastern Cape ANC branches underground and police raids of homes and workplaces of campaign leaders, including Luthuli, to confiscate Defiance Campaign documents, membership cards, organizational papers, and files. With the introduction of the Public Safety Act and the Criminal Law Amendment Act in 1953, the state could proclaim states of emergency; suspend the rule of law; expand its arrest powers; place restrictions on freedoms of assembly, speech, and movement; and ban the words and images of activists. The white electorate seemingly approved of these repressive tactics, as the Nationalists gained twenty-four parliamentary seats in the April 1953 elections. The judiciary was another instrument of domination; in addition to the December 1952 convictions of ANC leaders, the state convicted fifteen Defiance Campaign leaders in Port Elizabeth in 1953 of contravening the Suppression of Communism Act.20

Luthuli condemned the National Party’s “fascist dictatorship” and the “anti-Defiance Acts,” which evoked the “unfortunate Medieval Dark Ages.” Lamenting the apartheid “chain of bondage” that left Africans “prisoners in their own castle,” he nevertheless celebrated the significant domestic and international support for the Defiance Campaign’s fight for democracy and the “fundamental human rights of freedom of speech, association and movement,” which would achieve “racial harmony in the Union,” bringing South Africa into modern civilization.21 He felt that only an inclusive African nationalism, expressed by a broad ANC-led multiracial coalition, could defeat apartheid and create a postapartheid, inclusive, egalitarian, equitable, and democratic South Africa. In sharp contrast to National Party leaders, who cast apartheid as the solution to the supposed problem of multiracial societies and an international model for other racially mixed countries, Luthuli reconciled the seemingly oppositional political claims of national unity and racial diversity. “I personally believe that here in South Africa, with all our diversities of color and race, we will show the world a new pattern of democracy. . . . We can build a homogeneous South Africa on the basis not of colour but of human values.”22 His inclusive nationalism asserted the primacy of African claims based on their indigenous status, their numerical majority, and the longevity of their struggle. But unlike the Lembedist exclusive African nationalism of the 1940s, Luthuli did not present whites and other racial groups as foreigners, but as permanently settled South Africans.

Luthuli’s previous coordination with Natal Indian Congress (NIC) president G. M. Naicker, vice president J. N. Singh, and future NIC vice president Ismail Meer during the Defiance Campaign lessened lingering post–Durban Riots African-Indian tensions.23 As ANC president, Luthuli built “a political alliance based on a common, genuine spirit of friendship between our respective communities.” He organized a mass rally of several thousand people in Durban to protest the lack of educational facilities and opportunities for African and Indian children before police tossed him in jail.24 Undeterred, Luthuli presided over an ANC-NIC joint meeting in Durban to protest the Public Safety Bill and the Criminal Law Amendment Bill.25 Luthuli and Naicker issued a joint ANC-NIC protest statement from the “voteless and democratic peoples of South Africa,” who condemned Nationalist Party apartheid policies, and the ANC invited the NIC to join a planned stay-at-home during the national elections in April 1953, utilizing the same nonviolent principles used recently by bus boycotters in Johannesburg.26 Amidst government threats to repatriate Indian-descended South Africans back to India, Luthuli often addressed NIC conferences, expertly critiquing the Natives Land Acts, the Urban Areas Act, and the Group Areas Act as the primary cause, respectively, of the chronic landlessness, lack of urban property, and general insecurity of Africans in South Africa, which he compared to Nazi Germany. Naicker followed the call of Luthuli, “our President-General,” to commemorate June 26, 1953—the third anniversary of the murder of peacefully striking Africans by government forces, and the first anniversary of the Defiance Campaign—as Freedom Day, and urged all NIC branches to participate.27 This day became a sacred day of service and rededicated commitment to the freedom struggle in South Africa.28

New ANC president Luthuli gives the “Africa” sign to delegates at the December 1953 ANC national conference in Queenstown. Luthuli attended this conference despite his banning orders. (Bailey’s African History Archives, photograph by Bob Gosani)

In May 1953, the regime banned Luthuli, claiming that his political activities promoted “feelings of hostility in the Union of South Africa between the European inhabitants and the non-European section of the inhabitants of the Union.”29 The ban confined Luthuli to Groutville and the surrounding Stanger district and prohibited him from entering major South African cities, attending political meetings or public gatherings (defined as five or more people together in the same space), making speeches, and visiting ANC branches. With Special Branch police increasing their raids of Luthuli’s house in search of “subversive” documents, Minister of Native Affairs Hendrik Verwoerd denounced him in Parliament as a dangerous radical championing equal rights, and Prime Minister Malan called the ANC a terrorist group “on the pattern of the Mau Mau” in Kenya.30 South African authorities lamented that Luthuli, previously regarded as a “good Native[,] . . . had now been bought by the Indians and was definitely under Communist influence.”31

Escalating state and popular violence marked the 1950s. Luthuli and others advocating Gandhian nonviolent civil disobedience clashed with younger militants willing to consider armed self-defense in debates that surged to the fore during the Defiance Campaign. On November 9, 1952, the lay minister Luthuli delivered a sermon titled “Christian Life: A Constant Venture,” the basis for his manifesto “The Road to Freedom Is Via the Cross,” which compared apartheid South Africa to Nazi Germany and affirmed nonviolent struggle.32 Luthuli could not know that this very day would become known as Black Sunday, when police fired on ANC supporters praying with Defiance Campaigners in East London’s Duncan Village. Africans responded by burning government facilities; in the chaos, a few whites died, but militarized police killed two hundred–plus Duncan Villagers, according to estimates.33 The carnage raised doubts within the ANC about the efficacy of civil disobedience. The Criminal Law Amendment and Public Safety Act expanded government powers to crush antiapartheid dissent. Mandela, Sisulu, Mda, and the ANC Executive discussed armed self-defense and critiqued what seemed to be a “useless” nonviolent strategy, but for the time being they decided “it was politically wise” to maintain a nonviolent posture.34 Pivotal ANC leader Govan Mbeki encountered Mpondoland Africans who argued to him that whites’ superior firepower had facilitated their nineteenth-century conquests over Africans, who would not regain their independence until they had sufficient arms. Thus, the Defiance Campaign’s nonviolent tactics would not overthrow the state, but only “tickle the beard of the Boers.”35 In 1953, Sisulu embarked on a months-long tour of Romania, the Soviet Union, and China, whose armed struggle was inspirational to some South Africans, raising the possibility of armed self-defense with Chinese and Soviet officials.36 Sisulu later told Luthuli of other “revolutionary” stirrings, prompting the president-general to later admit that “non-Whites” appeared “ready at any time to change the non-violent aspect of our movement, to violence.”37 Luthuli made public assurances that “we do not mean to use violence in furtherance of our cause.”38 But beyond the public glare, he was also articulating militant thoughts. In a 1953 letter to his friend ANC leader Z. K. Matthews, Luthuli confided that he hankered to “fight for freedom” as American abolitionists once did, evoking the 1859 revolt of John Brown (and his black freedom fighters), who in killing slaveholders on the eve of the U.S. Civil War advanced the Law of the Israelites (Hebrews 9:22): “without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sin.”39