Читать книгу Churches of Nova Scotia - Robert Tuck - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Two

St. Matthew’s, Halifax:

Mather Church?

WHEN HALIFAX WAS FOUNDED IN 1749, it was peopled mostly with individuals rounded up in the poorer parts of London and shipped overseas to Nova Scotia. Within a very few years, many of them had perished from the cold, died in epidemics, or moved away. Their places were largely taken by a sharper and hardier sort of person from the Thirteen Colonies to the south, then still British subjects, attracted by the opportunities offered by the development taking place in Nova Scotia. Like the New England planters, who a little later on were settled on the lands from which the Acadians were expelled in 1755, they were, in religion, mostly dissenters from the established church of England, having learned their religion in Puritan congregations back home in New England. Before the end of 1749, Governor Cornwallis, in response to a request from the dissenters, gave four prime lots at the corner of Hollis and Prince streets that had been forfeited by their original proprietors (by reason of their failure to erect houses on them) as the site for a dissenters’ chapel. Its construction began in 1753, and in 1754 the Governor’s Council granted it £400. It was ready for use before the end of that year, and became known as Mather’s Church.

But who was Mather? No one knows for sure. Thomas Raddall suggested that the chapel was named after Cotton Mather, the New England Puritan Divine, 1663–1728, famous for having presided at the celebrated witchcraft trials in Salem, Massachusetts — although he had been dead for a generation. Until their own building was ready, the dissenters used St. Paul’s Church on the Grand Parade Sunday afternoons, their congregation consisting largely of the same persons who had already spent up to three hours at the Book of Common Prayer service of Morning Prayer and sermon at St. Paul’s. The first minister of Mather’s Church was the Reverend Aaron Cleveland, but after three years he left Halifax and went to England, where he took Holy Orders in the Church of England.

Perhaps Mather’s Church was a nickname. Officially it was called The Protestant Dissenters’ Church, but in popular parlance it continued to be called Mather’s Church, as its renaming as the phonetically similar St. Matthew’s Church in 1820 indicates. But by this time its congregation included a number of Presbyterians, and its early days as a Congregationalist stronghold with links to New England had faded.

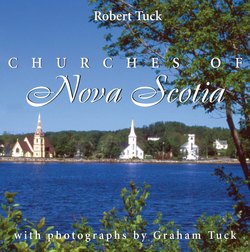

Photo by R.C. Tuck.

St. Matthew’s Church, Halifax: view from Old St. Paul’s burying ground.

Undoubtedly, the American Revolutionary War had something to do with this, for at that time, in the mid-1770s, the American rebels had sympathizers in the dissenters’ congregation — none more so than their minister, the Reverend John Seccombe. His expression of support for the Americans one Sunday in the summer of 1775 cost the church dearly. Four years earlier the congregation had been granted by the Crown sixty-five acres west of Oxford Street in an area bounded by South Street and Jubilee Road, and running down to the Northwest Arm, to serve as glebe land, very much as St. Paul’s Church had been given land in the north end of the city. On that Sunday a member of the navy and one of the military attended a service at the dissenters’ church and heard Mr. Seccombe not only pray for the rebels’ success in their war against the Crown, but also commend their cause to his congregation. Off they went and repeated what they’d heard to the authorities. The next day Seccombe was summoned to appear before the council and was charged with uttering treasonable thoughts. Three prominent citizens, Messrs. Salter, Fillis, and Smith, all members of the church, were also charged with treason. Happily, they and their minister were acquitted, for if found guilty in that day and age, and with a war on, they might well have been hanged. Seccombe was let off with a severe warning. But what really hurt was that the glebe land in the south end of the city that had been given to the church by the Crown was taken back and given to a senior military officer. In 1883, with the war over, the church requested its return. The request was refused, but the dissenters were offered instead an equivalent acreage of property in the vicinity of Armdale. Incredibly, they turned the offer down. After that, the authorities simply ignored the dissenters’ church’s requests for the return of the land it had been given and had lost — all because of a sermon.

After the American War of Independence, the Congregationalist element in the dissenters’ church waned and the number of Presbyterians increased. There were disputes between the two groups. The Congregationalists wanted ministers from New England, the Presbyterians ministers from Scotland; the Congregationalists wanted to sing hymns by Isaac Watts, the Presbyterians wanted to sing metrical psalms; the Congregationalists wanted Communion four times a year, the Presbyterians just once. According to historian Dr. Will R. Bird, the struggle between the two groups lasted three years until a settlement was reached and an agreement signed on January 16, 1787, under the terms of which the Congregationalists got the quarterly Communion and the hymn-singing they wanted, and the Presbyterians the minister from Scotland.5

Photo by R.C. Tuck.

St. Matthew’s Church, Halifax: interior.

In the nineteenth century, temperance and Sabbath-observance became landmarks of Protestant religion, but in Halifax, at least, in the previous century some Protestants were more relaxed on these points than they were later on, as the tale of two Presbyterian elders, members of St. Matthew’s, suggests. They were known to serve Communion in church Sunday mornings, and sell rum in their taverns Sunday afternoons. But this was before the rise and spread of Methodism that did so much to shape the attitudes of English-speaking populations in the Victorian era on both sides of the Atlantic.

St. Matthew’s in the eighteenth century was much like other churches, in that it was unheated and its seating was at first scanty and then uncomfortable, with worship services dominated by long-winded sermons, during which people tended to nod off and fall asleep. Dr. Bird vividly describes the Protestant dissenters’ church-going experience in Halifax in those early days:

It was very cold in the church during the winter months as there was no heat whatever. The minister wore a long, heavy cloak over his regular attire, a heavy, lined hood and fur mittens. Men attending church were so bundled and wrapped with scarves they could barely walk in. Women wore seven petticoats, many shawls and capes and woolen gloves. The more wealthy had servants to carry in foot warmers made of iron and holding live coals. Others had heated bricks wrapped in blankets to supply warmth. Three women had fat poodles they brought to church and used as foot warmers. In 1795 fashions changed. Women wore but one petticoat, cotton hose instead of woollen, low shoes instead of ankle high laced footwear, and low-necked gowns. Women caught cold and died from chills taken in church. So a stove was installed on either side of the sanctuary and stoked the night before a service to heat the building. Services were very long. A sermon could last one and a half hours. Prayers lasted from forty minutes to an hour, and the congregation stood. An intermission was always given halfway through the prayer so that the infirm might sit and be rested.

There was no Garrison Chapel in Halifax for years and soldiers sat in the right of the gallery at St. Matthew‘s, the artillery and engineers on the left. As the artillery wore white starched trousers and blue jackets with long tails they made a fine appearance, but if the men were out late on Saturday night the long service was apt to make them sleepy. A Sergeant-major always stood in the centre of the gallery with a bug pole which he used to prod awake any unfortunate who started to snore. The best pews in St. Matthew‘s sold for $144.00 per year and were to the left and right of the sanctuary against the walls. Those next to them sold for $100.00 per year. In the centre were long benches without backs and these were free seats for the poor and for single women and men. Pew rents were paid quarterly and if payments were not on time the pew was auctioned. During the period from 1784 to 1850 all the leading business men of the town attended St. Matthew‘s and a man‘s credit in Halifax was judged by where he sat in the Church.

Morning service at St. Matthew‘s in the period 1784 - 1857 began at 9:00 am with a recital of the bills on hand asking for remembrances in prayers. A member might ask the congregation to pray for his wife or mother or child who was ailing. Another might ask for prayers on behalf of members of the family at sea, or prayers for a son or brother gone to the United States and not heard from. As the Bible chapter was read, it was explained verse by verse, and might take the better part of an hour. Afternoon service began at 2:00 pm and it was then that matters of offence were heard. The minister would read from the pulpit charges of slander. Mrs. White might accuse Mrs. Black of spreading false rumours, and would have witnesses to back her statements. Mrs. Black, if she had any hint of such proceedings would have her own witnesses. After slander cases came cases of debt. One member would name another who owed him but would not pay. Third were charges of flirtation. A wife would charge another of flirting with her husband. Last in the list were charges of drunkenness, and these were mostly made by the minister.6

In rural parts of Nova Scotia, the public recitation of sins by the sinners themselves was a feature of some Protestant revival services into the early years of the twentieth century, and provided not only an occasion for the sinners to come clean about their transgressions and receive an assurance of pardon, but also a source of inside information for those curious about their neighbours and their doings. Such services often attracted large congregations.

The old St. Matthew’s Church burned on New Year’s day in 1857, together with many other buildings in downtown Halifax. It was rebuilt on a new site (the present one) on Barrington Street, purchased from Bishop Binney, who lived nearby on the other side of Government House. The new St. Matthew’s preserved the basic concept of the old building’s meeting house interior layout, with a central pulpit in front of one end wall with galleries around the other three sides, but on the exterior it took the form of an elegant Gothic-Revival-Style church with stucco finish and a buttressed tower surmounted by a slender spire. It was designed by Cyrus Thomas, 1833–1911, one of two architect sons of William Thomas, who designed the St. Lawrence Market and the Don Jail in Toronto. Cyrus was also the architect of the Halifax courthouse, just up the hill from St. Matthew’s, on the opposite side of St. Paul’s cemetery from the church. But the courthouse is in Classical, rather than Gothic, Style; Thomas, like Stirling and some other architects of that era, used Gothic for ecclesiastical, and Classical Style for civic and secular buildings.

Today, St. Matthew’s takes pride in being the congregation of earliest foundation in the whole of the United Church of Canada.