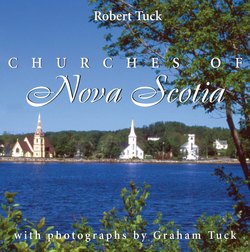

Читать книгу Churches of Nova Scotia - Robert Tuck - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Three

St. Mary’s, Auburn:

Decency and Order

THE BUILDER OF ST. MARY’S Church, Auburn, Bishop Charles Inglis, was a native of Ireland who served United Church of England and Ireland parishes in Delaware and New York until his Loyalist sympathies alienated him in the United States after the American rebellion. When he arrived in Nova Scotia in 1787 as the newly consecrated first Anglican bishop in what was left of British North America, he was determined to see that everything in religion in the colony should be “done decently and in order,” as St. Paul had counselled the Corinthians (1 Cor. 14:40). St. Mary’s Church, built in 1790 in the neo-Classical Georgian Style at Auburn in the heart of the Annapolis Valley, is very much the embodiment in architecture of decency and order.

However, at the end of the eighteenth century, and for some time thereafter, the religious scene in Nova Scotia was anything but orderly, and Inglis’s “Anglican Design in Loyalist Nova Scotia” (as historian Judith Fingard calls it) fell some distance short of fulfillment.7 It was a time when life for many was harsh and primitive, and enthusiasm (the word comes from the Greek en theos: “in God”) in religion offered an excitement and release that the ordered cadences of the Anglican liturgy rather failed to provide. Nevertheless, over time decency and order made an impact, and although a majority of the colonists did not become Anglicans, their meeting houses became more and more like churches, with steeples and symbolism and eventually, in some cases, even a liturgical interior layout.

But Anglicanism itself was also subject to change, largely generated from within, in what is usually called the Tractarian Movement (from the tracts, or pamphlets, its members published to propagate their views). It began in the University of Oxford in England in 1833 with a sermon preached by the Reverend John Keble in which he argued that the established Church of England and Ireland was not a mere department of the state, but the ancient Church of the British Isles. It was a view that accorded well with the contemporary romantic fascination with the lore and legends of the Dark and Middle Ages, and the Gothic revival in architecture that accompanied it. As the nineteenth century proceeded, the Tractarian Movement produced changes not only in theology and liturgy, but also in the look of church buildings. Some of these changes can be traced in St. Mary’s Church, and are evident also in many of the churches of all denominations in Nova Scotia. Indeed, our idea today of what a church looks like has been largely shaped by Tractarian and associated influences.

Photo by Graham Tuck.

St. Mary’s Church, Auburn, 1790: exterior.

St. Mary’s Church had a steeple and a liturgical layout inside from the start — although the interior today differs from that of 1790. The chancel then was shorter, consisting of little more than a small railed-in sanctuary accommodating only the holy table, or altar, and a pair of chairs set below a large Palladian-style window in the east wall. In front of it was a three-decker pulpit, perhaps placed in the centre in front of the altar, but possibly on one side under the chancel arch. The parish clerk, who led the responses of the congregation, many of whom would not have been able to read, occupied the desk at the lowest level of the pulpit, while the minister sat above him to recite the divine office and read the lessons. The third level towered over them both, and was topped by a sounding board. It was occupied by the preacher during the sermon, which could go on for a long time. Many pulpits had an hourglass, which enabled the preacher to gauge the length of his oration, and he might turn it over once or twice in the course of his delivery if he was particularly long-winded. One of the nineteenth century rectors of St. Mary’s, the Reverend Richard Avery, whose thirty-three year incumbency, from 1852 to 1887, is the longest in the history of the parish, is recorded as always writing out his sermons in full “to make sure against saying anything in preaching that was not entirely correct” — yet it was he who, in 1856, took the three-decker pulpit apart, separating the clerk’s desk from the rest of the structure.8 This was the first impact the Tractarian Movement had on St. Mary’s, for one of the goals of the Tractarians was to restore an even balance between Word and Sacrament in Anglican churches. Pulpit and lectern were no longer to dominate the altar, or preaching to overshadow the Holy Communion, as in the Georgian era with its enormous pulpits and celebrations of the Sacrament only once a quarter. Decency and order in Anglican worship now had to make room for the numinous as well. It was a shift that would have a profound effect on the architecture and appearance of churches.

Photo by Graham Tuck.

St. Mary’s Church, Auburn: interior. The panels on the end wall of the nave are of the Coat of Arms of the Diocese of Nova Scotia (left side) and King George III (right side), and are said to have been painted by Bishop Charles Inglis.

The next things to go at St. Mary’s were the box pews. The church was full of them, up a step from the floor of the alley that ran down the centre of the nave. Their sides were so high that when the worshippers sat down they could not see one another, and were visible only to the parson and the clerk in the pulpit. Each pew had its own door which, when shut, cut down draughts and kept in heat, for sometimes people brought hot bricks to church, and sometimes their dogs, on which to rest their feet in cold weather. Each pew at St. Mary’s was numbered, and the pews were rented, thereby providing the parish with an important part of its income. Several pews were reserved: No. 1 was for “strangers,” No. 16 for the bishop, No. 17 for members of the Rector’s family, and No. 24 for “coloured people.” Pew No. 9 was reserved for the Governor, but since his appearances at St. Mary’s were infrequent it too was rented, on the understanding that its usual occupant would sit somewhere else when his excellency appeared. A pew was reserved for the bishop because Charles Inglis made his rural retreat, Clermont, a few miles west of Auburn, his principal residence after 1796.9 About 1865, the sides of the box pews were lowered and given scroll-shaped tops, and their doors were removed. At the same time, the pew rents were abolished and anyone was free to sit anywhere they wished in the church.

Other changes involved the acquisition, in 1862, of a hand-pumped organ in a Gothic case, which was placed in the original part of the gallery at the west end of the nave (it had been extended in 1828 across the nave windows along both the north and south sides of the building). The gallery in Georgian churches normally accommodated singers and musical instruments as well as the occasional overflow congregation. But by the 1890s this arrangement for the placement of the singers and musicians seemed old-fashioned, for the new Gothic Revival churches then being built had extensive chancels, opening out from their naves and packed with choir stalls designed to accommodate the new, robed choirs that were being formed, whose members took delight in being seen as well as heard. It was a fashion that Canon Johnson of New York later described as “Cathedralesque Chancelitis.”10 So it was that, in 1891, St. Mary’s small sanctuary was moved fifteen feet to the east. This placed it beyond the grave of Dr. Charles Inglis, the bishop’s grandson, who had been buried just outside the church in 1861 and would, from now on, be under the floor as well as in the ground. Between the sanctuary and the nave, a chancel with choir stalls and organ alcove was created, the organ alcove on the south side balanced by a new sacristy on the north elevation. This gave St. Mary’s a neo-Gothic layout, although all the other architectural elements in its fabric remained in the neo-Classical tradition. In respect to this anomaly, St. Mary’s is like St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, which although executed in the neo-Classical Renaissance Style, has the floor layout of a large medieval Gothic church.

So while much has changed at St. Mary’s since 1790, much remains the same. Most of the small panes of glass in the large, round-headed nave windows are those installed more than two hundred years ago when large sheets of glass were unavailable. Only in the east window, where a fine portrait of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Child was installed in 1895, has the original glass been replaced. The old plaster on the walls still retains as part of its composition quahog shells left nearby on the Fundy shore by dispossessed Acadian settlers as they awaited transport into exile in 1755. And most of the original shingles remain on the walls, fastened to wide, old, hand-hewn boards with the square-headed, Nova-Scotia-forged nails that were brought by soldiers on their backs ninety miles from Halifax, on foot, in the spring of 1790. The finish of the church — from the decorative wooden keystones in the window surrounds and the pediments that adorn the exterior gables, to the cornices and fluted columns of the interior — is superb.

The architect and builder of St. Mary’s Church was William Matthews, from the military ordnance department in Halifax. Much of it is of pine, felled and milled locally. The soil in Auburn is sandy, and hospitable to pine — although today there are few specimens left as magnificent as the trees that ended up in the fabric of St. Mary’s Church.

Its first rector was the Reverend John Wiswall, a Loyalist and former Congregationalist minister who had taken Anglican orders in 1764 and seen his church at Portland, Maine, burned by rebels in 1775. Its first benefactor was Colonel James Morden (after whom the nearby village of Morden, on the Bay of Fundy, is named), who played a role similar to that performed by the lord of the manor in an English country parish. A chalice and paten given by Bishop Inglis in 1790, a 1753 Bible, two long-handled wooden collection boxes, panels bearing the coats of arms of King George III and of the diocese of Nova Scotia — both said to have been painted by Bishop Inglis himself to hang over the governor’s and the bishop’s pews respectively — and two panels bearing the Ten Commandments and the Lord’s Prayer flanking the holy table on the east wall, are among the treasures preserved in St. Mary’s Church.

Of course, the church itself is its own chief treasure. But wooden churches are vulnerable to fire, and two-hundred-year-old timbers particularly so. St. Mary’s has had at least one very close call with fire. On the night of Saturday, September 20, 1981, at 2:45 a.m., the spire of the church was hit by lightning, and set ablaze. A crowd gathered, and four fire departments from nearby towns arrived only to discover that their ladders and the pressure in their hoses were inadequate to get water to where the flames were burning down the length of the spire. The rector, the Reverend Langley MacLean, called on all present to pray that the church might be saved. Some knelt and some stood — and the prayer was answered almost immediately: a gust of wind carried the water to the flames, and the fire was put out. Father MacLean claimed credit not only for the prayer, but also for his having sprinkled the entire building with holy water two weeks earlier!

When St. Mary’s was built in 1790, documents relating to its construction were placed in a gilded copper ball on the weathervane on the spire. Several times over the years the ball has fallen to the ground, usually in windstorms, and each time the documents have been copied and replaced in the ball on its return to the spire. In 1981, the old documents suffered water damage and had to be dried out and sent to Ottawa for restoration. This time copies were placed in the ball when it was put back. A lightning arrestor was added, made in the shape of a cross.

In 1986, the 1891 vestry on the north side of the chancel was replaced by a small church-hall building, designed by architect Ron Peck to blend architecturally with the church.

St. Mary’s is the earliest of seven Charles-Inglis-era churches in the Annapolis Valley. The others are at Clementsport (St. Edward’s, built in 1795), Karsdale (St. Paul’s/Christ Church, 1791–1794), Granville Centre (1814–1826), and Annapolis Royal (St. Luke’s, 1815–1822) at the western end of the Valley, Cornwallis (St. John’s, 1804–1810) near the eastern end, and old Holy Trinity at Middleton (1789–1791) in the middle, twelve miles west of Auburn. The Cornwallis and Granville Centre churches are so similar to St. Mary’s in their proportions and fenestration as to suggest that they, too, were drawn by William Matthews. Holy Trinity, Middleton, and St. Edward’s, Clementsport, have been replaced for regular use by Gothic Revival alternatives built a century later. In Middleton, the town grew up a mile or so east of the church, making its location inconvenient to a majority of the parishioners. At Clementsport, the location of St. Edward’s at the top of a hill prompted the erection of a new building lower down in order to spare worshippers the steep climb — although the factor that determined the decision to construct the new church might well have been less the steep climb and more the erection of a Baptist church at the foot of the hill. In both cases, the old churches became neglected and dilapidated through disuse, only to be rescued and restored as the twentieth century advanced and brought with it a growing appreciation of heritage architecture. Because these buildings are not used very often, they have undergone little change. Stepping into St. Edward’s, with its box pews, white plastered walls, small-paned and round-headed windows, and old pine woodwork is like going back in time into the eighteenth century.

Photo by Graham Tuck.

Photo by Graham Tuck.

Photo by Graham Tuck.

Photo by Graham Tuck.

Photo by Graham Tuck.

More Inglis era churches, previous page top and bottom: St. Edward’s, Clementsport, 1795; All Saints’, Granville Centre, 1791–1826; Top left: Holy Trinity, Middleton, 1789–91; Bottom left: St. John’s, Cornwallis, 1804–12. Above: St. George’s, Sydney, 1785

One might think that the concentration of these Colonial-era Anglican churches in the Annapolis Valley indicates a large and flourishing Anglican population in that part of Nova Scotia at the end of the eighteenth century. In actual fact, they were built, with the assistance in many cases of government money, to try to stem the tide of enthusiasm that had swept in from New England before the American rebellion and that many Loyalists — particularly Charles Inglis — perceived as being subversive not only of decency and order, but also of attachment to the Crown.