Читать книгу The Grand March - Robert Turner - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

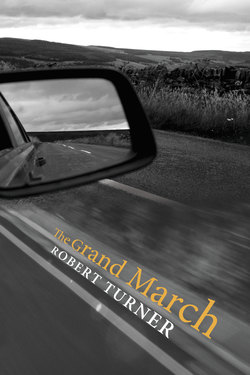

Оглавление“These wipers are about useless,” Russell Pinske muttered, partly to himself and partly to see if he could get a response from the woman curled in shadows beside him. She didn’t move. He peered through the bug-spattered windshield into the darkness ahead and wondered, not for the first time, what he was doing with her.

Onward to the promise of dawn, he steered the speeding car along an unlit country highway. The two-lane route shot straight across flat Indiana farmland, but he had to compensate continually for the car’s tendency to drift left. Dense woods brooded in the moonless night. Fireflies mingled with the Milky Way. The only signal the old AM receiver could pick up was a gospel station broadcasting from a place he’d never heard of. Open windows fanned the stale smell of sun-bleached vinyl car interior. The sleeping woman began to snore again. Gloria Arbogast owned the car.

They had known one another for a couple of years, but hadn’t spoken in months when they met by chance on the cross-town bus as both were preparing to leave Cincinnati. Russell had sold almost everything he owned and was off to his hometown of Door Prairie before beginning a trek westward. Gloria was going to Toronto to participate in an intensive summer program studying abnormal frogs. She suggested they leave together, an idea that was funny to him. A month ago he was certain he’d never see her again. Now they were on the road in her cranky old Ford Fairlane in the middle of the night.

He knew the way by heart. The road would curve ahead and enter an uninhabited stretch of dreary marshes that was part of a game preserve. By his reckoning they’d be in town around sunup. The gospel station grew fuzzy. He adjusted the tuning and then switched it off, wondering why they couldn’t pick up any of the stations out of Chicago. The glow of the city should soon be visible, a purple-orange aura on the western horizon. Rank marsh water perfumed the humid air. Gloria sighed and shifted her position, throwing one arm over the edge of the seat. The car roared on.

A large moth hit the glass with an audible splat. He’d long since depleted the car’s reservoir of wiper fluid, and was sickened by the dry blades merely smearing the gummy remains into the mélange that had been accumulating for hours. Not that there was much to see in this swampland, nothing but a scum-ridden slurry of shallow streams. He eased off the accelerator, mindful that some bored state trooper might be out hunting for a fool like himself. Something about the thought of being stopped by a cop made him need to urinate, so he pulled off the road near a bridge that crossed the Kankakee River. After finding relief on its banks he returned to the car for a cup, intending to fetch some water and wash the windshield. Gloria awoke as he rummaged through his pack in the back seat.

“What are you doing?” she asked with a drooping mouth, her head propped on the window. Her voice startled him.

“Sorry,” he mumbled, struggling with a strap on a compartment of his pack. “I’m going to clean the windshield. I can’t stand looking at bug guts anymore.”

He grabbed a cup and a rag.

“I used up all your fluid, there wasn’t much left,” he said, backing out of the car. He leaned into the front seat to tell her, “Man, you need new wipers.”

She looked at him placidly and shut her eyes. He left the door open and went back to the river. She reached over and closed it, then stretched out on the bench seat.

“Hey, can you turn the light on?” he called out upon his return. She lifted a weary hand and flipped the switch. He cleaned the glass and the wipers, then stashed his gear and started the motor. They rolled back onto the road and got up to speed.

“Car’s pulling to the left pretty bad. Could be your front end.”

She grunted. He looked at her and continued.

“Hope it makes it to Detroit.”

“I’m going to Toronto,” she said with a sigh, her head resting on her hands and her eyes tightly closed.

“Yeah, well, I’m saying I hope it makes it to Detroit.”

She yawned and buried her face in her arms.

A hint of light touched the eastern sky. They approached a town that greeted its visitors with large stone markers mounted with rusted ship anchors. Whenever he came through here, he wondered what significance these anchors held for this landlocked farming community. He’d never bothered to find out, but now thought that his open-road adventure ought to include learning about places like this. He stopped at the next junction. The route they were on went through the lake counties and into Chicago. He turned north. Straight ahead lay Door Prairie, and Michigan beyond. Stars faded in the blushing dawn. The moist air was strangely sweet.

He looked at her in the light from the dashboard. Her face wore an unguarded expression, one he saw as stern, even dour. Together they had formed a relationship of convenience. He valued their conversations, and the witty acuity she brought to them. She found in him a quality of canine fidelity. He was attentive and loyal and she thrived on that companionship, not having many close friends in her life. At one time she tried to buy into his laid-back lifestyle, but couldn’t work up much enthusiasm for it. He was a line cook, without any apparent desire to advance beyond that. Whatever ambition he had came in fits and starts, and seemed to her to be misplaced anyway. She was a serious person, now beginning graduate work in the field of environmental science, specializing in wetlands ecology.

Problems arose when they tried to move beyond using each other, when they sought to forge a stable platform for their disjointed lives. That platform collapsed last winter, after many creaks and groans, when it became apparent that he had some idealized notions of their romance that she did not share. She wouldn’t even call what they had a romance, and scoffed at his sentimental earnestness, hoping to snap him out of it. But when he continued to lay bare his innermost soul, she hardened against what she considered to be his gratuitous sincerity. The depth of his feeling unnerved her. She simply had never felt swept off her feet, certainly not in the way he claimed to have been. He accused her of indifference, which she refused to dispute. When he began insisting that she start caring about him, it was clear they were done. Done for good, he had thought, yet here they were.

After their breakup Russell began to spend more time with people he hadn’t seen much during his year of preoccupation with Gloria. He sought out one friend in particular, Johann, a woodworker by trade. Johann ran his shop out of the basement of his house, which became Russell’s primary hangout. He appreciated his friend’s craftsmanship, and found it satisfying to watch him create a piece from beginning to end. The idea of a completed work appealed to him. Although he took pride in his cooking, his meals didn’t last. He began to long to accomplish something lasting.

Johann suggested he start writing a journal, advice Russell took and practiced daily for a few months. When he read back over everything he’d written, he was depressed by the banality of it all. It was then he decided to hit the road. Things needed shaking up, and he couldn’t think of a better way to do that than by packing up and leaving town. He had always wanted to see the Pacific Ocean, so that was something he could accomplish. If nothing else, his journal entries would certainly become more interesting.

Russell quit his job, gave notice to his landlord, and sold everything he couldn’t carry with him. While he waited for his final paycheck he took long walks around the city, trying to work up a properly adventuresome spirit. The best he could muster was a combination of exhilaration and trepidation. It was on one of these expeditions that he ran into Gloria. He was happy to go along with her idea to leave town together, not only because it saved him money on a bus ticket, but because he thought it would do him some good to leave on friendly terms with her. The plan was for him to drive through the night while she slept; then she could take over and continue on fresh in the morning.

Yesterday he stuffed his belongings into his backpack and went to see Johann one last time. There he was presented with an ornate walking stick that Johann had made for his journey. The top was carved into an over-large acorn, supported by the tails of four grinning squirrels. Oak-leaf scrollwork twined down to a thick bronze tip. It was an accomplished work, and Russell gratefully accepted the gift. He took his first walk with it when he hiked over to Gloria’s with his backpack. They had dinner together, then got on the road. She fell asleep around midnight, shortly after they crossed into Indiana. He’d driven almost the entire length of the state and was nearing the southern curve of Lake Michigan, the place where he had grown up that now seemed so foreign.

He was laying rubber across land once covered by glaciers, and marked by prehistoric tribes with their mysterious mounds. Trappers had tramped with the Potawatami until both were displaced by garrisons of soldiers who built forts and trading posts to supply westward wagon trains. Towns slowly accreted on what they called the portal to the prairie, and with the railroad came more schemes and scams, successes and failures, loves and losses. His own people, drifting in from all over, decided to make a go of it here, at least for a while. He wished he knew their stories, but all his relations were scattered and distant. He could imagine them, though: plainspoken folks in their kitchens, their perfect flaws intimately warping the space around them.

Gloria snorted and snapped her eyes open. “Where are we?” she asked with a yawn. She sat up and ran her hand through her tangled hair.

“Just about twenty miles away or so.”

She cleared her throat and fished a fresh pack of cigarettes from her purse. Last he knew, she had quit smoking. He smiled to see her light up with the Zippo that he’d given to her. She lazily exhaled out the window. The silence wearied him.

“Over there used to be a barn,” he started, indicating a field to the right. “The Party Barn. All through high school we’d go out there and get drunk and stuff. Nobody owned the place; it was just abandoned property. But a couple years ago some kids were partying a little too heartily and burned it down.”

She recoiled at the thought of a party barn, at the notion of cheap booze and sweaty teenagers. He rambled on, oblivious to her displeasure.

“A neighbor of mine, kid I grew up with, got killed on these tracks coming up. Train dragged him, like, a quarter mile or so before it stopped. Sixteen years old and wham—”

He snapped his fingers, then read the look in her eyes and shut up. She snuffed her cigarette, then took out a compact and primped a bit. They entered Door Prairie.

About thirty thousand souls dwelled in this county seat that had thrived during the heady days of the Rust Belt and had declined along with it. Some manufacturing remained, most famously production of the meat slicer found in delicatessens across the country, but lately the town council had begun to focus on revitalizing the languishing tourist economy. Back in the Jazz Age it had been one of Chicagoland’s bucolic retreats, and the plan was to resell it as such.

He drove along the old Lincoln Highway that served as the main street. A downtown beautification project was underway around the monumental courthouse towering over modest buildings of brick and stone. Groups of migrant workers stood around in parking lots, either waiting for a ride or seeking a job in the fields. Every spring waves of wandering farmhands came through, most from Mexico. Two of the friends he was here to see, Carmela Contreras and Manny Fuegas, were part of the resident Hispanic population, as was the current mayor.

While they waited at a red light, he offered to buy her breakfast. She accepted with thanks. Somehow he liked her better when he could do something for her. He felt an echo of the satisfaction that had filled him in their early days, when it was clear he was providing her with something she needed. They drove to a restaurant where the hospital he’d been born in had once stood.

He ordered up a mess of protein; she asked for fruit and oatmeal. After testing her coffee with a sip, she excused herself and left the table. Forms of cars glided across the shaded windows. A man in a business suit read a newspaper at the counter. An elderly couple ate wordlessly in the next booth. The decor relied on neutral colors, brass rails, and hanging baskets of silk plants. He peered through the rough weave of the shade. For the first time he felt wobbly facing his future, acknowledging the range of things he could do and places he could go. The air conditioning felt good. It was going to be a hot day.

She slid back into the booth and smoothed her hair. He watched her bony wrist as she stirred an ice cube into her coffee. Her dull nails were chewed and ragged. The whirlpool in her cup absorbed her black eyes. With her face turned down in the warm morning light, she looked like a stranger to him. And she was. For all her foibles and follies he could enumerate, all her preferences and moods he knew so well, he realized as they sat together in this restaurant that she was more mysterious to him now than when they first met. He knew that he might never see her again.

She was trying to calculate how far her US dollars would stretch in Canada.

“When are you going back to Cincinnati?” he asked, because he felt he had to say something. She stopped stirring and sipped her coffee.

“Over Labor Day. Why?”

He shrugged. “Curious.”

“Where do you think you’ll be?” she asked while glancing out the window.

“I don’t know.” He raised his brow and shook his head. “California, I’m guessing. I’m going to stay here awhile, look up some friends.”

Their food arrived. She asked for skim milk to add to her coffee. He caught sight of a familiar face behind the counter. The cook was someone he knew, but the name escaped him. He turned his attention to his omelet. The old folks finished their meal and shuffled off. Gloria and Russell ate in silence. He wolfed down his eggs and was attacking his toast when she asked him for directions.

“You can get out of town on this road here. It’ll take you to 94 north into Michigan. Got me from there. Do you have an atlas? I’ve got a pocket one you can have.”

She bit a piece of cantaloupe before answering. “No, there’s one in the car. So this goes straight to the highway?”

“Yeah, it’s about ten miles. Maybe more. Less than twenty.” He paused and set his toast aside. “Listen, I want to thank you for getting me up here, even though it was out of your way.”

With a dismissive wave she said, “That’s OK. I’m happy to help you out. Besides, it’s shorter for me to drive from here than it would have been to drive the whole way.”

“Well, anyway, there’s a gas station up the road—I’ll fill up your car.”

“OK,” she said, after a spoonful of oatmeal. “Thanks.”

He swigged the last of his coffee. She ate her cereal. When the waiter came around, Russell got a refill and asked for the check.

“So, you were born here?” she asked, dropping her spoon in her bowl and wiping the suggestion of a smile away with her napkin. He thought to tell her that this was, in fact, the very parcel of land that marked his entrance into the world, but refrained from informing her of the specifics.

“Yeah,” he began. “I haven’t been back in a few years. Still have good friends here. Family’s all moved away. It’s a weird place. I’m thinking I’ll get caught up with my friends, see what’s up, try to find a ride out west. Just see what happens. Who knows?”

The waiter brought the bill. Russell finished his third cup of coffee; Gloria left half of her first cup. A steamy parking lot greeted them as they stepped out the door.

“So, the gas station’s just up here,” he said, nodding in the direction.

She leaned close and whispered, “You have the keys.”

He barked out a little laugh and fumbled for the keys in his pocket. She walked behind him as he approached the passenger-side door. Before he unlocked it he stopped, turned, and kissed her.

In a flash she struck out in a roundhouse slap that connected with his temple, sending his glasses flying. He dropped her keys and went scrambling for his glasses.

“What the hell,” he spluttered.

She snatched the keys off the pavement and glared at him. “What do you mean? You tell me what the hell.”

He squashed his glasses back on his face. She opened the car door, grabbed his backpack and hurled it to the pavement.

“I’m sorry,” he said, going for his pack. “It was just an impulse.”

He picked up his pack and quickly scanned around to see if anyone was watching this scene. The lot was empty. They faced each other. To him, it looked like she expected something.

“Can I still buy you gas?” he tried with a weak smile.

“Goddamn,” she blurted, then slammed the door and cranked the ignition.

“No, really,” he said, reaching out a hand. The transmission coughed and the car lunged into reverse. He stepped aside and watched her leave. As he slouched over his backpack and pondered his next move, it occurred to him that she’d driven off with his new walking stick.