Читать книгу The Grand March - Robert Turner - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеThe hot pavement shimmered under a climbing sun. Russell sighed and looked down the road where Gloria had left, then strapped on his pack and walked slowly, trying to find the posture that most comfortably carried the weight on his back. That walking stick would be useful about now, and he regretted its loss. He’d already grown fond of it, as he did with certain objects. By nature he was something of an animist. He once had a bicycle that he would pat and stroke like a pet, and he had even been moved to hug a mailbox after dropping in a letter. Down the road he came to the small grocery store that used to deliver orders to his grandparents’ house. A sturdy old woman struggled out the door, a wagon filled with goods squeaking behind her. She stopped, kicked the rear axle and walked on, the wheels now rolling silently.

He meandered past the house where he’d grown up. Things had sure changed since his great-grandfather settled here after emigrating from Russia at the outbreak of the First World War, but the house he’d built and the neighborhood he’d built it in remained largely the same. It was a place of simple wood-frame homes and small garden plots. Russell was the third generation to be raised in the house, after his grandfather Charles and mother Liz, and he was the last. That was about all he knew of the history of his family, one that had disintegrated by the time he was aware enough to be curious.

What little he did know, he’d pieced together from fragments of stories that had stuck in his memory. He knew he was an accident, one that his parents did their best to put behind them. His birth did briefly unite Dick Pinske and Liz Czanderra in matrimony. The marriage, tenuous at best, didn’t last long. By the time Russell was five, his father had remarried and relocated out of state, dropping out of Russell’s life for good. His mother, about that time, entered graduate school at Northwestern, then began an academic career there. She told her parents that she didn’t want to uproot Russell, and she arranged to keep him with his grandparents indefinitely.

So his childhood unfolded in the kind indulgence of Charles and Alma. They kept him fed and in school and provided for him as best they could, with Liz sending money but showing up rarely. Russell was an easygoing kid content to hide away for hours with his books and the worlds they took him to. He cultivated his fertile imagination and developed a knack for making friends, talents that would serve him well.

Charles died when Russell was fifteen. Alma couldn’t cope on her own, so Liz had to step in. She moved back and began commuting the sixty miles to Chicago each day while Russell finished high school. She hated it in Door Prairie, and spent as little time as possible there. Once Russell was on his own, Liz beat it back to the city for good. Alma sold the house and went to live with her diabetic sister in northern Michigan. It was during this time that the deep friendships he’d formed nourished him in ways his fractured family could not.

The idea of going to college was appealing, but even with scholarships he balked at the expense. A friend told him about a culinary school in Cincinnati and he went to check it out, reasoning that kitchen skills would prove practical. He liked it there and decided to stay. The city seemed romantic to him, a well-worn place of sagging brick that stood like a natural outcrop on the eroded hills. There was something dreamy in the air of that river valley, and indeed the years passed as in a dream. It was nice while it lasted, but it had come to a dead end.

He wound his way in the shade of trees by the renovated marina and praised the town’s investment while making use of the newly built public toilets. The breeze came cool off the lake as he sat in the park under a leaning oak. From there he could see the extent of the development: rows of new condominiums and docks. He got up and walked along a trail. The woods were still moist with dew, the foliage and spider’s webs jeweled with sun-glazed droplets. He came to a swimming beach, where he took off his pack and sat on a bench by a playground. The beach was empty, except for a man playing with his dog. Russell searched through his gear for a canteen he’d packed away. He pulled out half of his stuff before he found it, and spent a good deal of time re-packing, trying to make it all fit again. He filled the canteen from a water fountain then headed toward the fairgrounds and the last known address of Helen Kolopnok.

Russell and Helen had met six years ago, when he had just turned eighteen and she was going on twenty-five. They were introduced at a high-school graduation party thrown by the parents of Carl Paulette, one of Russell’s closest friends. Helen had been invited to the party by Carl’s older sister, who was a nurse at the hospital where Helen volunteered. They hit it off right away, and spent most of the evening making wry observations about the increasingly inebriated partygoers. Before she left she gave him her phone number. He called the next day and they became fast friends that summer, sharing their stories and enjoying each other’s company.

They had last seen each other four years ago, when she’d gone with him to Carmela and Manny’s wedding. That night she told him all about a difficult relationship she’d been in that had recently ended, and thanked him for lifting her spirits. He was glad to oblige. They’d stayed in touch, but gradually the frequency of their communication declined. Now while he walked down her street, he felt bad that he wasn’t even sure she still lived here.

He consulted his old pocket watch. It was pretty early, but she always made a big deal about being a morning person, so he thought she’d most likely be up. She might even be at her summer job, if she had one. Her main livelihood came from managing the rental properties of her parents, but most every summer she took a part-time job for both supplemental income and experience. A carpet of wildflowers surrounded the house, colorful evidence that this was still her place. He climbed the steps and read the names on the two mailboxes, one for H. Kolopnok and another for M. Petersen. That would be Myrtle, he figured, the upstairs tenant Helen had described as “splenetic.” He stood on the porch. Her door was slightly ajar. Wind chimes tinkled. The butt of a cigar rested in an old tuna can next to a wicker chair. Her collection of blown-glass paperweights had grown. They used to line the window ledges, but now also adorned most of the porch railing.

“Helen?” he called out as he knocked on the screen door. “Hello, Helen?”

The interior door jerked open. He was confronted with a gaunt, blotchy old woman whose blue hair twisted wildly out from her scalp like extruded strands of gunmetal. She took a step back, her floral-print muumuu billowing about her shrunken form.

“What do you want?” she demanded, scrutinizing him through squinty eyes.

“I was looking for Helen. Is she home?”

She put her hand on the edge of the door and replied sternly, “I don’t know you.”

“I’m Russell,” he gave a halfhearted wave. “Russell Pinske. A friend of hers. Are you Myrtle?”

“I said I don’t know you.”

“Well, I’m a friend of Helen’s. She mentioned you once to me.”

She thought about this, then said, “She never said anything about it.”

“Yeah, I haven’t actually talked to her in a long time.”

In a niche on the far wall stood a statuette of St. Christopher that Helen had always displayed. It was something he’d entirely forgotten about, and the sight of it set him adrift in a flood of memories until the old woman responded.

“Doesn’t sound too friendly to me.”

He shifted the weight of his backpack and returned his attention to the conversation. “Is she home? I just got in town and I’d like to see her.”

“I’m not saying a thing,” she said, closing the door a little and placing more of herself behind it.

He craned around to more fully face her. “Could you tell her Russell came around? I’m sure she’d like to know.”

“Don’t be so sure,” she told him, then slammed the door and loudly threw the bolt.

Either he’d forgotten that downtown was pretty noisy, or there was more traffic running through here than there used to be. A few blocks along Lincoln Way, the town’s thoroughfare, he came upon a local furniture dealer and was greeted by a novel sight. In the parking lot was a king-sized canopy bed with a high mattress and fluffy comforter. A sign hanging from the canopy identified it as “The Celestial Bed.” Beside the bed stood a fat man in a tasseled nightcap and flowing nightgown, waving to passersby with a glittery wand topped by a silver star.

Russell walked on and was glad to see the usual contingent of bums loitering around the Red Rooster Inn, open for business already. Carl used to tend bar there, but now he worked an office job in Chicago, commuting from the town of Stillwater, about twenty miles southeast, where he and his girlfriend, Ellie Sellers, lived. He talked to Carl a week ago and told him about what he was up to. They’d get together somehow, but it was uncertain when, as was just about everything else in his life.

In the window of a shop he saw one of the posters that was part of the new tourist initiative, reprints of advertisements first produced in the Twenties. They were stylish renderings of bobbed beauties and dapper gents enjoying the charms of the Indiana duneland. A couple of years ago Carmela had sent him a print depicting well-heeled couples on Door Prairie’s lawn-bowling greens. During the years he’d been away she’d kept him abreast of local developments, like the old tractor factory being turned into a shopping mall and the expansion of the marina on Long Lake, largest of the town’s nine lakes. He called her the day he sold the poster, and they discussed his planned trip. She insisted that he come see them before heading off to points unknown, so here he was.

He left the main drag and made his way down a cobblestone alley behind old warehouses, then crossed the tracks and cut through the parking lot of the roller rink on his way to where he thought his friends lived. Twenty-one Melon was the address he had for the house they’d bought shortly after their marriage. He didn’t know exactly where Melon was, but knew it was by Lily Lake, on the east side of town.

The street took him past a foundry and a scrap-metal yard, then into a residential area built on a low rise above the blue ellipse of Fox Lake. Bulging roots of sycamores buckled and broke the sidewalks. He took the road that wound out to Lily Lake, a fair-sized body of dark, still water ringed by lily pads. He stopped in the weeds on the side of the road to get his canteen from his pack. As he drank he looked across the street at the overgrown acreage that was once owned by Door Prairie’s most notorious citizen, known locally as Nellie Widow. Her gruesome exploits were popularized in all manner of lurid publications and duly chronicled by the county historical society.

Early in the twentieth century a woman calling herself Nellie Harper advertised in lonely-hearts newspapers for eligible bachelors to come visit her at her farm, luring them with livestock and land. She used a hatchet to dispose of seven unfortunate suitors, along with three children and two farmhands before the brother of her last catch took his fears to the police. Her house burned to the ground as an investigation got underway. The remains of her victims were found in a pit in the cellar, chopped up and covered with quicklime. A female corpse was recovered from one bedroom, but it had been decapitated, and a positive identification was impossible. Witnesses said the body belonged to a woman much smaller than beefy Nellie. She was reportedly seen in California the following year, and sightings persisted along the West Coast for a decade or so. The case was never resolved.

Melon was to his right, directly opposite the heavy steel gate that barred vehicles from entering the desolate, old farm. Hot and tired, weighed down and unsteady, Russell trudged in dirty gravel beside broken asphalt. So far the exhilaration of the open road had proven elusive, while a profound weariness was inescapable. He questioned the wisdom of his enterprise, this so-called adventure that now seemed like a played-out folly. On his first day he was already despairing. The house to his left was a ramshackle, cinderblock eyesore whose mailbox bore no address. House numbers here were apparently assigned at random. Next to number 9 was number 14, across the street from number 11. Seventeen was next to 14, across from 12 and 15. An empty lot on his left flanked what turned out to be number 21, on the corner.

The place was real nice, right across from the lake, a two-story, old, craftsman-type house with a wrap-around porch and a climbing rose on a trellis. It looked like it had been painted recently, a clean, creamy white with lavender trim. Behind the house was a barn-like garage. Three large maples and a tulip tree stood in the open yard, the property demarcated by a pile of rocks at the curve in the road, and by a weed-entangled fence next to the empty lot. Up by the steps they’d stationed the pink flamingoes he’d given them on their wedding. He took off his pack and set it on a stool painted in fine Carmela style. On the seat she’d drawn a menacing crab, and between the outstretched pincers were the words: “Sit At Own Risk.” He knocked. A fish-shaped windsock hung limply from the eaves. The blanket of lilies heaved in rhythmic ripples. He knocked again. There was no car in the driveway. He sighed, more pessimistic than before about his prospects here. A corner of the curtain was drawn back, then the door opened and Carmela stepped out.

With a little squeal, she wrapped her arms around him and exclaimed, “You’re here! We were just talking last night about what you were up to. I even called down there, but your phone’s disconnected. Manny said you’d blown us off and you were probably in Timbuktu already, but I knew you’d come.”

She stepped back, bobbed her head, and shimmied her shoulders. Sunlight poured across her smooth cinnamon skin; her dark eyes danced above high, smiling cheeks. She wore her black hair in a thick braid that hung down half the length of her spine. The bridge of her proud nose crinkled as her smile spread, dissipating any gloom still shadowing his thoughts.

“I’m glad you’re home,” he said. “Hope I’m not showing up too early.”

“Oh no, not at all. Manny’s at work already. I didn’t know if I heard you knocking or not. I’m in my sewing room in the back. We usually use the side door.” She turned and waved him into the house. “Come in. I’m right in the middle of something.”

He placed his pack inside and closed the door after him. The room was appointed with furnishings that were threadbare in a genteel fashion, a funky array of rummage-sale finds. A faded oriental rug covered the central portion of an oak floor. Carmela had decorated the top foot or so of the walls with the intricate designs she was always doodling, a variegated band of geometric patterns that twisted and flowed with a suggestion of movement. The whole effect was subtle but striking. It must have taken a long time to complete.

“You’ve been busy,” he commented, stopping in the middle of the room. She turned and followed his gaze up to her handiwork.

“Yeah, I did that last year. I’ve started the kitchen cabinets. See?” She walked into the kitchen and pointed to the outlines sketched on the corners of the cabinet doors. “But I’m kind of stalled out on it.”

He nodded to indicate that he knew what it was like to be stalled out.

“Hey,” she continued, “I’ll show you around later, OK? I’m doing some alterations for my mom now—I’ve got to get them down there by nine, when they open.”

He raised an eyebrow and pulled out his watch. “It’s almost nine now, isn’t it?”

“No, quarter till eight.” She indicated a clock on the far wall.

“Oh, man.” He smacked his forehead. “You guys are in a different time zone, aren’t you?”

She laughed. “Time zone. I don’t know why, but that makes me laugh. Time zone.” She repeated it once more in a slow monotone, then shook her head and said, “Come on.”

She led him through a set of French doors into a small room down the hall from the kitchen. “This was just a closet, but Manny and my brother Felix expanded it for me to work in. I was set up in one of the bedrooms, but if we ever have babies, we’ll need all our bedrooms.”

She sat behind her sewing machine and took up her work with a whispered sigh. Folded clothes sat on her table, among scraps of material, boxes of thread and other items of her craft. An iron stood steaming on its board. The shelves held linens embroidered with her motifs. A needlepoint sampler she’d made when she was a child was framed on the wall.

“It’s nice in here,” he observed.

“They did a good job,” she said, tinkering with her bobbin. “Manny got the cool old doors from a salvage yard. He got these natural spectrum lights for cheap, too. They’re great—I can see true color in here when I do my needlework, like working in sunlight.”

He sat in a plush armchair, feeling comfortable in the moment. She zipped along in her sewing.

“I’m sorry I didn’t call and tell you what was going on,” he said. “I had to wait for my check, then I hung around to cop a ride off Gloria.”

“What’s the deal there, you and Gloria?” she asked, head bowed to her task.

He rolled his eyes and slumped. “Oh, I’ll tell you about it later. I can’t even think about it now. It’s just too stupid is all.”

“OK,” she replied.

Her machine ratted and tatted, her eyes were fixed in concentration. Russell noted the proximity of their place to the old widow’s farm.

“Actually, that’s one of the reasons we bought this place,” she told him. “It’s really a beautiful piece of land, and the city owns it. The real-estate agent said they were going to annex it to the rest of the park, but I guess the deal hasn’t been worked out yet, ‘cause nothing’s happened so far. Remember going out there and being scary and stuff?”

She grabbed a pair of pants from the stack in front of her and held them up. They had an enormous waist. About three Carmelas could have fit inside them.

“Now that’s scary.”

She folded the pants and said, “Hey, go get the phone book. It’s in the kitchen on top of the fridge. I’ll show you something funny I noticed the other day.”

“All right,” he said as he stood. “But explain your street numbers to me.”

“Talk to Manny about that. You know him. It drives him crazy.”

He returned with the book and stood leafing through it.

“So you see what they’ve done,” she said, directing his attention to the format of the listings. “They strung together the name and the street, and it’s just odd the way it reads. Look up Manny.”

He read: “Fuegas Manuel Mr. Melon.” It made him smile.

“Now check out W, the last Weaver,” she suggested.

“Weaver Wanda Mrs. Walnut.”

She snorted. “Don’t you think they were made for each other?”

He put the book down. “Oh, Carmela, you even make the phone book fun.”

“It’s all in how you look at things,” she let him know.

His mood now fully brightened, he poked through her work on the shelves and pulled out some linens to admire.

“These are lovely.”

She stopped working and addressed him with a serene expression. “Thank you.”

“Hey, you know things that make you laugh, like time zone and Mr. Melon?” he asked, folding her things and putting them back on the shelves. She looked at him gamely, and he continued. “I walked by the roller rink coming down here. Is that old guy still there on the Wurlitzer?”

She confirmed the continuation of the organist at the establishment, and he resumed his discourse.

“Just about anything that guy says will make me laugh. It’s that drone he has, I guess, when he calls out the skating routines, or whatever they’re called—you know? When you have to skate a certain way?”

“Couples skate. Promenade two by two.” She imitated his hypnotic drawl perfectly.

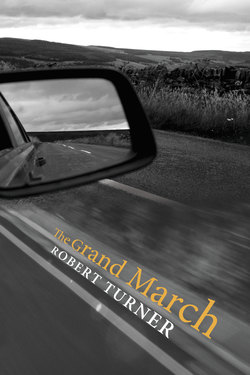

“Yeah, that’s it. There was one, I forget what you were supposed to do, but I cracked up when he said it: ‘Let The Grand March begin!’ It all just seemed so absurd somehow—that cheesy organ playing, people skating around, everybody doing their thing. I don’t know why it was so funny, but it was. I totally lost it.”

“Guess you had to be there,” she said distractedly, putting the final stitch in her last article. She got up and unplugged the iron. The phone rang.

“It’s my mom,” she predicted as she walked into the kitchen to answer it. He followed and helped himself to a glass of water.

“Yes, Mom,” she was saying while making goofy faces at him. “Yes, I just finished. As soon as I get off the phone with you, Mom.”

She hung up and returned to her sewing room. He stayed in the kitchen, drinking his water and checking out her sketches on the cabinets. She packed her work in a milk crate, then took it through a door off the kitchen and strapped it to a rack on her bike. She returned, quickly went down the hall and came back with a helmet on her head.

“Help yourself to anything,” she offered. “Manny might be home for lunch. I’ll be home this afternoon. I’ve got errands to run for my mom, then I’m going over there to start cooking for this big family thing tonight, all the kids and cousins and everybody. You can come, too, if you want.”

He nodded and placed his empty glass in the sink, then followed her out the door. They stood on the porch.

“If you leave, just pull the door closed behind you and it’ll lock, but you have to slam it pretty hard. There’s a foldout kind of couch-bed thing in the room right next to my sewing room. Get some rest. You must be tired.”

She smiled at him as she coasted off. Near the end of the driveway she turned and waved.

“I’m glad you’re here, Russ.”